Berton Roueché

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pionicer Newspaper of Ocean County. 5 Vents a Copy

PIONICER NEWSPAPER OF OCEAN COUNTY. 5 VENTS A COPY TOMS RIVER, 31. J, FRIDAY. APRII. », 1920 KWABIWUKW IS» VOLERE To .NUMBER js " , . OF WORK FOB REN “JOE" THORFNON IS -TOO H AILS SHOT TO PIKt'F.S NO ONI OPPOSED DAM AT *>1) TEAMS IN THIS SECT 10 X POOt TO RTS HtH CONGRESS" llltt Iti: 1*0 8 ITS REPORTED BV OCEAN lOt.NTV BANKS I’lHUt HEARING VESIERDAT Bank Assets Deposits In the past month or ho the xnmrently there 1» no lack of work In some parts of the Third Consrea-1 malls have again loom all shot to nvrtt and teams in this section of slonal district they have a brand new Lakewood Trust Company $2.!»20.T;m>.70 $2 553.463 10 No one appeared yesterday to op- First N'attonal, Toms River 1,180,387.81 1,124,76012 pieces, It has been as iliilicult to fsvse the project of damming Toma ■ . «hore In addition to the ordinary and bona fide reason for uppoal.i* i get mall mailer through as It »a» “ok of aprlna. which 1c enough on "Joe" Thompson of New Ksypt for Ocean Co. National. Pt. Pleasant 1.113,716.28 961,368 JO River at the public hearing In ibo Peoples National, Lakewood ■ 1,153,488,27 959,294.84 •luring the curly months of tots, courthouse on Tbi vday, April 8. at , ms and the rmtda to keep teams the Republican nomination for coo- when the war paralysed the mall ' i teamsters busy, there are a nutn- gress this fall. -

Baggage X-Ray Scanning Effects on Film

Tib5201 April 2003 TECHNICAL INFORMATION BULLETIN Baggage X-ray Scanning Effects on Film Updated April 8, 2003 Airport Baggage Scanning Equipment Can Jeopardize Your Unprocessed Film Because your pictures are important to you, this information is presented as an alert to travelers carrying unprocessed film. New FAA-certified (Federal Aviation Administration) explosive detection systems are being used in U.S. airports to scan (x-ray) checked baggage. This stronger scanning equipment is also being used in many non-US airports. The new equipment will fog any unprocessed film that passes through the scanner. The recommendations in this document are valid for all film formats (135, Advanced Photo System [APS], 120/220, sheet films, 400 ft. rolls, ECN in cans, etc.). Note: X rays from airport scanners don’t affect digital camera images or film that has already been processed, i.e. film from which you have received prints, slides, KODAK PHOTO CD Discs, or KODAK Picture CDs. This document also does not cover how mail sanitization affects film. If you would like information on that topic, click on this Kodak Web site: mail sanitization. Suggestions for Avoiding Fogged Film X-ray equipment used to inspect carry-on baggage uses a very low level of x-radiation that will not cause noticeable damage to most films. However, baggage that is checked (loaded on the planes as cargo) often goes through equipment with higher energy X rays. Therefore, take these precautions when traveling with unprocessed film: • Don’t place single-use cameras or unprocessed film in any luggage or baggage that will be checked. -

"Life Should Not Be a Journey to the Grave with the Intention of Arriving

"Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming "Wow! What a Ride!" — Hunter S. Thompson Read a book, watch a foreign film, do something you’ll be ashamed of, run naked, brazen, and screaming down the road of life! Don’t worry if you fall down, because after you get back up, dust yourself off, remember : chicks dig scars! —Nathan Schubert I‟ve never tried to complicate life. Try to be happy, travel the world, and experience anything you can get your hands on. This mindset has driven my passion for reading, movies, and travel; for me there exists little more to the human experience than trying to digest as much of this world as possible in our short time here. This has slowly led me towards teaching, to hopefully inspire that spark of curiosity, to fan the embers of possibility, to embolden that glimmer of imagination in a young student. Because missing out on the best things in life for the simple reason that no one ever showed you where the entrance was makes Nathan a very dull boy. Finding a Message Amongst the Horror: An I-Search Nathan Schubert Spring, 2011. “Give them pleasure - the same pleasure they have when they wake up from a nightmare.” —Alfred Hitchcock The darkness was suffocating. Its oppressive weight bore down upon me, closing in for the kill. -

John Carpenter Halloween (Original Soundtrack) Mp3, Flac, Wma

John Carpenter Halloween (Original Soundtrack) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Stage & Screen Album: Halloween (Original Soundtrack) Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Soundtrack, Score, Experimental, Minimal, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1282 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1373 mb WMA version RAR size: 1461 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 758 Other Formats: AIFF AAC DTS AHX DMF DXD APE Tracklist A1 Main Theme From "Halloween" A2 Boyfriend And Susan A3 Illinois Smith's Grove A4 Myers' House A5 At School Yard B1 Behind The Bush B2 Row 18 Lot 20 B3 Doctor And Sheriff In The Myer's House B4 Doyle Residence B5 The Night He Came Home B6 End Title Companies, etc. Made By – Nippon Columbia Co., Ltd. Credits Composed By – John Carpenter Performer – Bowling Green Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra Notes Limited pressing with "Spacesizer 360 System Recording". LP housed in poly bag, cover included OBI strip. Includes 4 page insert. Back cover states "Joy Pack Film" presents. Labels states date of August 1979 "℗ '79. 8" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Halloween (Original John Motion Picture STV 81176 Varèse Sarabande STV 81176 US Unknown Carpenter Soundtrack) (LP, Album, Club) John Halloween (Original VSC-81176 Varèse Sarabande VSC-81176 US 1983 Carpenter Soundtrack) (Cass) Halloween (Original John Motion Picture STV 81176 Varèse Sarabande STV 81176 US 1983 Carpenter Soundtrack) (LP, Album) Halloween (Original John CL 0008 Filmmusik) (LP, Celine Records CL 0008 Germany 1989 Carpenter Album, RE) Halloween (Original John 115980 Soundtrack) (CD, Marketing-Film 115980 Germany 2003 Carpenter Album, Ltd) Comments about Halloween (Original Soundtrack) - John Carpenter Pryl Interesting...I don't think the value of the OG presses will go down though. -

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

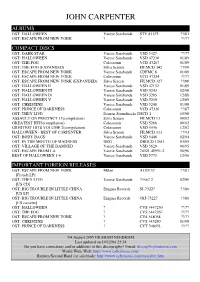

John Carpenter

JOHN CARPENTER ALBUMS OST: HALLOWEEN Varese Sarabande STV 81152 ??/81 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK ? ? ??/?? COMPACT DISCS OST: DARK STAR Varese Sarabande VSD 5327 ??/?? OST: HALLOWEEN Varese Sarabande VSD 47230 01/89 OST: THE FOG Colesseum VCD 47267 01/89 OST: THE FOG (EXPANDED) Silva Screen FILMCD 342 ??/00 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Varese Sarabande CDFMC 8 01/89 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Colesseum VCD 47224 ??/?? OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (EXPANDED) Silva Screen FILMCD 327 ??/00 OST: HALLOWEEN II Varese Sarabande VSD 47152 01/89 OST: HALLOWEEN III Varese Sarabande VSD 5243 02/90 OST: HALLOWEEN IV Varese Sarabande VSD 5205 12/88 OST: HALLOWEEN V Varese Sarabande VSD 5239 12/89 OST: CHRISTINE Varese Sarabande VSD 5240 01/90 OST: PRINCE OF DARKNESS Colesseum VCD 47310 ??/87 OST: THEY LIVE Demon Soundtracks DSCD 1 10/90 ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13(compilation) Silva Screen FILMCD 13 09/92 GREATEST HITS(compilation) Colesseum VSD 5266 09/92 GRESTEST HITS VOLUME 2(compilation) Colesseum VSD 5336 12/92 HALLOWEEN - BEST OF CARPENTER Silva Screen FILMCD 113 ??/93 OST: BODY BAGS Varese Sarabande VSD 5448 02/94 OST: IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS DRG DRGCD 12611 03/95 OST: VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED Varese Sarabande VSD 5629 06/95 OST: ESCAPE FROM LA Varese Sarabande 74321 40951-2 06/96 BEST OF HALLOWEEN 1-6 Varese Sarabande VSD 5773 12/96 IMPORTANT FOREIGN RELEASES OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Milan A120137 ??/81 [French LP] OST: THEY LIVE Varese Sarabande 73367.2 02/90 [US CD] OST: BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA Enigma Records SJ-73227 ??/86 [US LP] OST: BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA Enigma Records 4XJ-73227 ??/86 [US cassette] OST: HALLOWEEN ? CVS 3447230 ??/?? OST: THE FOG ? CVS 3447267 ??/?? OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK ? CVS 348038 ??/?? OST: CHRISTINE ? CVS 345240 01/90 OST: PRINCE OF DARKNESS ? CVT 348031 ??/?? ©4 August 2005 GRAHAM NEEDHAM Last updated on 10/12/04 23:54 Do you have corrections and/or additions to this discography? Email: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.cybernoise.com/ Rarities/Second Hand for sale/trade: http://www.cybernoise.com/mocyber.htm . -

Impact of Audiovisual Culture in Roberto Sierra's

Dalí’s Eccentric Imagination: Impact of Audiovisual Culture in Roberto Sierra’s Sch SILVIA LAZO University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Abstract From the appearance of sound film in the late 1920s to the spread of media outlets such as television and personal computers to today’s video-enabled mobile phones, the immediacy of audiovisual culture has changed the way people navigate and manipulate content. Visual images often instinctively induce aural and musical associations, and vice versa. Yet musical analysis in audiovisual culture often presumes the constraint of the visual on the musical (i.e., the primacy of a visual product over its accompanying music). In this paper, I take a diverging approach. I present Roberto Sierra’s Sch. as a case study for the effects of multimedia technology in a twenty-first- century composer’s creative process and product, which conjures up the imagination in historical and contemporary ways. This investigation complements research in music analysis, film music, and music pedagogy in relation to audiovisual culture by highlighting the mutually influential effects of musical and visual cultures. Keywords: Latin American music, audiovisual culture, music imagination. Resumen Desde la aparición de la película sonora a finales de la década de 1920 hasta la difusión de los medios de comunicación, como la televisión y las computadoras personales, hasta los teléfonos móviles de vídeo, la inmediatez de la cultura audiovisual ha cambiado la forma en que las personas navegan y manipulan el contenido. Las imágenes visuales inducen instinctivamente asociaciones auditivas y musicales, y vice-versa. Sin embargo, el análisis musical en la cultura audiovisual a menudo supone la limitación de lo visual en lo musical (es decir, la primacía de un producto visual sobre su música acompañante). -

|||GET||| Behind the Fog 1St Edition

BEHIND THE FOG 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Lisa Martino-Taylor | 9781315295206 | | | | | Fog, First Edition Or maybe if your boss puts it on your desk We use cookies to enhance your experience on our website. No trivia or quizzes yet. Herbert creates the perfect blend of over the top with gruesomeness This is one of those books I really wanted to love more considering Herbert is kind of a UK horror icon, however, I only half loved it. Diya finds people by reaching out to a lot of nonprofit groups and she is always aware of representing a broad cross-section of the people who end up on the streets. Other Editions Antonio Bay is actually Point Reyes Station. The more visceral sections are quite good, but they're not Behind the Fog 1st edition for long and the author is not operating at a level near them for much of the book. He is up there with Stephen king for me and is truly Talented I Picked up this book when I was a teen, on holiday, It was a book left in my aunty and uncles holiday Villa, I got into a few pages and it truly disturbed me to the core, to the point where I even felt I was far too young at the time to be reading such a scary book. There were a few scenes that felt dated, and of course, 40 years on, the technology is going to be antiquated, but Behind the Fog 1st edition is all of little consequence, and I hardly noticed. -

100 Piano Classics

100 Piano Classics: In The The Best Of The Red Army Lounge Choir Samuel Joseph Red Army Choir SILCD1427 | 738572142728 SILKD6034 | 738572603427 CD | Lounge Album | Russian Military Songs Samuel Joseph is 'The Pianists' Pianist'. Born in Hobart, Re-mastered from the original session tapes, the recordings Tasmania he grew up performing at restaurants, events and for this 2CD set were all made in Moscow over a number of competitions around the city before settling in London in years. They present the most complete and definitive 2005. He has brought his unique keyboard artistry to many collection of recordings of military and revolutionary songs celebrated London venues including the Dorchester, the by this most versatile of choirs. Includes Kalinka, My Savoy, Claridges, the Waldorf and Le Caprice. He has Country, Moscow Nights, The Cossacks, Song of the Volga entertained celebrities as diverse as Bono to Dustin Boatmen, Dark Eyes and the USSR National Anthem. Hoffman along with heads of state and royalty. Flair, vibrancy and impeccable presentation underline his keyboard skills. This 100 track collection highlights his astounding repertoire Swinging Mademoiselles - The Adventures Of Robinson Groovy French Sounds From Crusoe - Original TV The 60s Soundtrack Various Artists Robert Mellin & Gian-Piero SILCD1191 | 738572119126 Reverberi CD | French FILMCD705 | 5014929070520 CD | TV Soundtracks Long before England started swinging in the mid-1960s, One of the most evocative children's TV series of the 1960s France was the bastion for cool European pop sounds. is equally matched by Robert Mellin and Gian-Piero Sultry young French maidens, heavy on mascara and a Reverberi's enchanting score familiar to any young viewer of languid innocence cast a sexy spell with what became the period. -

The Impact of a Book Flood on Reading Motivation and Reading Achivement of Fourth Grade Students

THE IMPACT OF A BOOK FLOOD ON READING MOTIVATION AND READING ACHIVEMENT OF FOURTH GRADE STUDENTS by SHERRY MARIE ANDREWS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN READING EDUCATION 2017 Oakland University Rochester, Michigan Doctoral Advisory Committee Linda M. Pavonetti, Ed.D., Chair James F. Cipielewski, PhD. Bong Gee Jang, Ph.D. Anica G. Bowe, Ph.D. © Copyright by Sherry Marie Andrews, 2017 All rights reserved ii I dedicate this dissertation to my family and friends. A special thank you goes to my loving and supportive husband, John and daughter, Nicole who have made numerous sacrifices and tirelessly supported me throughout this journey. I will always appreciate all that you both have done. I also dedicate this dissertation to my mother, Velma for instilling the love of reading by playing recorded stories on the record player when I was a child. I know that you have watched over me from heaven as I have aspired to reach the goals that you said were possible. To my father, Orice, when I began this journey I never thought that you would not be present when I crossed the finish line. Your tenacity and spirit have kept me centered and focused. Sincere appreciation is extended to my siblings, Antionette and Orlando for their encouragement and unyielding confidence in my ability to complete this endeavor. To my cousin, Norma, who has been a constant source of inspiration and moral support. To my friends Janet and Joanne who provided a place for respite and never grew tired of listening to my ramblings. -

Blu-Ray Titles

BLU-RAY DISC ASSOCIATION CES 2007 Blu-ray Disc: The Leader in HD Entertainment Current and Upcoming Title Releases∗ Currently Available 16 Blocks The Ant Bully 25th Anniversary: Live in Amsterdam The Architect 50 First Dates ATL Aeon Flux Basic Instinct 2 All the King’s Men Behind Enemy Lines America’s Soul Benchwarmers American Classic The Big Hit Annapolis Black Hawk Down Blazing Saddles Goal: The Dream Begins Blues Gone in 60 Seconds The Brothers Grimm Good Night and Good Luck Bubble The Great Raid The Covenant Haunted Mansion A Christmas Story HDNet World Report – Shuttle Club Date: Live in Memphis Discovery’s Historic Mission Crash Hitch Dark Water House of Flying Daggers The Descent House of Wax The Devil Wears Prada Ice Age: The Meltdown The Devil’s Rejects Into the Blue Dinosaur Invincible Eight Below The Italian Job Enemy of the State Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back Enron – The Smartest Guys in the Room John Legend – Live at the House of Fantastic Four Kingdom of Heaven Firewall Kiss Kiss Bang Bang The Fifth Element Kiss of the Dragon Flight of the Phoenix A Knight’s Tale Flightplan Kung Fu Hustle Four Brothers Lady in the Water Freak ‘N’Roll…Into the Fog The Lake House The Fugitive Lara Croft – Tomb Raider Full Metal Jacket The Last Samurai Glory Road The Last Waltz Go League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Lethal Weapon Space Cowboys Lethal Weapon 2 Species Little Man Speed Lord of War Stargate Memento Stealth Million Dollar Baby Stir of Echoes Mission-Impossible III Superman – The Movie Mission Impossible – Ultimate Missions Superman II – The Richard Donner Cut Collection Superman Returns Monster House S.W.A.T.