Utopia Or Bust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

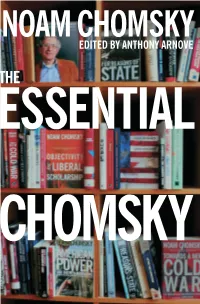

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

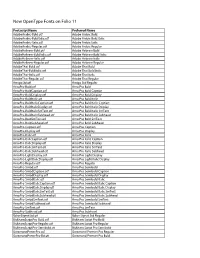

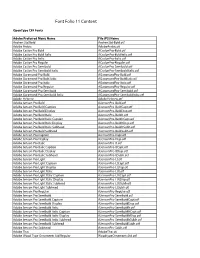

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Green Illusions Is Not a Litany of Despair

“In this terrific book, Ozzie Zehner explains why most current approaches to the world’s gathering climate and energy crises are not only misguided but actually counterproductive. We fool ourselves in innumerable ways, and Zehner is especially good at untangling sloppy thinking. Yet Green Illusions is not a litany of despair. It’s full of hope—which is different from false hope, and which requires readers with open, skeptical minds.”— David Owen, author of Green Metropolis “Think the answer to global warming lies in solar panels, wind turbines, and biofuels? Think again. In this thought-provoking and deeply researched critique of popular ‘green’ solutions, Zehner makes a convincing case that such alternatives won’t solve our energy problems; in fact, they could make matters even worse.”—Susan Freinkel, author of Plastic: A Toxic Love Story “There is no obvious competing or comparable book. Green Illusions has the same potential to sound a wake-up call in the energy arena as was observed with Silent Spring in the environment, and Fast Food Nation in the food system.”—Charles Francis, former director of the Center for Sustainable Agriculture Systems at the University of Nebraska “This is one of those books that you read with a yellow marker and end up highlighting most of it.”—David Ochsner, University of Texas at Austin Green Illusions Our Sustainable Future Series Editors Charles A. Francis University of Nebraska–Lincoln Cornelia Flora Iowa State University Paul A. Olson University of Nebraska–Lincoln The Dirty Secrets of Clean Energy and the Future of Environmentalism Ozzie Zehner University of Nebraska Press Lincoln and London Both text and cover are printed on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled). -

LOGO STANDARDS GUIDE 1 Murray City Identity

UPDATED August 2019 MURRAY CITY IDENTITY LOGO STANDARDS GUIDE 1 Murray City Identity TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 3 LOGO GUIDELINES GENERAL CITY LOGO SIGNATURE . 5 LOGO CONSTRUCTION . 6 CITY GROUPS . 9 TYPEFACES . 13 CLEAR SPACE AND MARGINS . .14 CITY COLOR PALETTE . 15 LOGO USE . 17 LOGO APPLICATIONS FORMAL STATIONERY . 23 STATIONERY TEMPLATES . 24 ENVELOPES . 25 BUSINESS CARDS . 26 GENERAL PAPER APPLICATIONS . 27 APPAREL . 28 FIRE DEPARTMENT APPLICATIONS . 29 POLICE DEPARTMENT APPLICATIONS . 31 VINYL APPLICATIONS . 32 RETIRED LOGO’S . 33 2 I N T R O D U C T I O N Murray City is unique . Our convenient location, strong independence, accessible government, and engaged citizens all work together to create a remarkable community . Murray City will strive to maintain our unity through a distinct brand and visual identity . Graphic identity is an important part of an organization . A logo or corporate symbol represents the people and products of an organization as well as the reputation it has achieved . 3 The Murray City brand combines the rich heritage of our community with its inherently progressive nature—but more importantly, it creates a symbol which universally represents the city. The “Circle M” mark replaces a diverse array of symbols that were previously used; the overall look and feel unites all areas of city government under one powerful and sophisticated image. The Murray City brand not only enhances the image of our city, it also serves to immediately identify it. Its effectiveness depends on proper and uniform usage on everything from a business card to the door of a city truck to the literature that is sent throughout the country representing our city. -

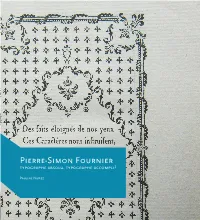

Pierre-Simon Fournier Typographe Absolu, Typographe Accompli?

Pierre-Simon Fournier typographe absolu, typographe accompli? Pauline Nuñez ¶ • °≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠° ≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°± Pierre-Simon Fournier * typographe absolu typographe accompli ? ≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°± °≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠° • ¶ Racines 04 Éléments biographiques Éléments de style Œuvre 18 Le Manuel Typographique Utile aux gens de lettres : vision encyclopédiste de l’art typographique ? Fournier réformateur et innovateur Fournier ornementaliste baroque Quelques exemples de caractères baroques en Europe. Fournier créateur plagié Après Fournier 52 Les admirateurs, les « continuateurs » Le revival Fournier chez Monotype Que reste-t-il de Fournier aujourd’hui ? Repères bibliographiques 72 Rue des Sept-Voies, aujourd’hui rue Valette. Atget, 1925. racines Jean Claude Fournier anne-Catherine Guyou (Auxerre, ? – ?, 1729) († le 13 avril 1772) un Fils1 imprimeur à Auxerre Jean-pierre l’aîné Charlotte Madeleine piChault pierre siMon le jeune Marie Madeleine Couret de VilleneuVe (Paris, 1706 – Mongé, 1783) († l1764) (Paris, 15 sept. 1712 – Paris, le 8 oct. 1768) († le 3 avril 1775) Jean François fils Marie elizabeth Gando trois filles antoine siMon pierre2 MarGurite anne de beaulieu († le 27 nov. 1786) elizabeth Françoise (13 sept. 1759 – ?) (14 août 1750 – ?) († le 10 oct. 1786) Marie Marie anne bruant adélaïde († le 5 sept. 1788) sophie (?) a. F. MoMoro un Fils, beaulieu-Fournier une Fille (guillotiné en 1794) un Fils qui prît plus tard le nom de Fournier 1. Probablement nommé François. Jean Claude Fournier, imprimeur à Saint-Dizier 1775 – 1791, est peut-être son fils. 2. Parfois appelé «le jeune».Fournier, imprimeur à Saint-Dizier 1775 – 1791, est peut-être son fils. Éléments biographiques. Pierre-Simon Fournier naît le 15 septembre 112 à Paris au sein d’une famille déjà ancrée dans le monde de l’imprimerie. -

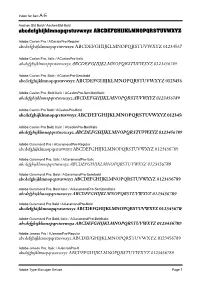

Adobe Type Manager Deluxe Page 1 Index for Set: A-E

Index for Set: A-E Aachen Std Bold / AachenStd-Bold abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Adobe Caslon Pro / ACaslonPro-Regular abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 012345678 Adobe Caslon Pro, Italic / ACaslonPro-Italic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Caslon Pro, Bold / ACaslonPro-Semibold abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567 Adobe Caslon Pro, Bold Italic / ACaslonPro-SemiboldItalic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Caslon Pro Bold / ACaslonPro-Bold abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456 Adobe Caslon Pro Bold, Italic / ACaslonPro-BoldItalic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro / AGaramondPro-Regular abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro, Italic / AGaramondPro-Italic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro, Bold / AGaramondPro-Semibold abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro, Bold Italic / AGaramondPro-SemiboldItalic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro Bold / AGaramondPro-Bold abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Garamond Pro Bold, Italic / AGaramondPro-BoldItalic abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 Adobe Jenson Pro / AJensonPro-Regular abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0123456789 -

Linotype Library Gold Edition 1.7** September 2002 See Page 2 2

Linotype Library Font Collections This document contains the following two lists of fonts: 1. Linotype Library Gold Edition 1.7** September 2002 see page 2 2. Linotype Library Website Fontlist 1999 February 1999 see page 32 ** This old version 1.7 is presently – October 2005 – still sold by Linotype Library GmbH. Since laymen cannot spot forged fonts (Public prosecutors and criminal court judges may study the report "The Funny Font Forging Industry"- http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/forgers.pdf), those who want to buy a Linotype font should insist that Linotype supplies an expertise by an independent lawcourt forgery expert guaranteeing that the Linotype font you intend to purchase is not a forgery. If the Linotype foundry does not supply full warranties, you should not buy any Linotype fonts: "I would recommend to obtain full warranties from the foundry that the typefaces do not infringe any rights anywhere in the world" (Niel Ackermann of Hewitsons Solicitors). Furthermore, those who buy a Linotype font should know that the Linotype Library GmbH secretly, i.e. without informing you, inserts your private address and other private data into the font bought by you: Since October 2005 Linotype distributes free of charge the font management spyware „FontExplorer X“ (see http://www.linotype.com/fontexplorerX). With such spyware, it is easy to collect private data about the font users. Those who do not want that their private data (e.g. private address, bank account number, credit card number etc.) are secretly inserted, as shown above, by Linotype into the fonts purchased should avoid to buy any Linotype fonts, and those who do not want that Linotype collects private data about your person should avoid to use any spyware, and those who do not want to buy any forged typefaces should insist that the Linotype Library GmbH supplies – prior to purchase – an expertise by an independent typeface expert guaranteeing that the font you intend to buy is no forgery. -

Fournier Le Jeune's Work Was Widely Accepted During the Rococo

FOURNIER TYPOGRAPHIQUE SPECIMEN Fournier Typographic Specimen �� LES CARACTERES DE L’IMPRIMERIE PAR FOURNIER LE JEUNE The characteres of Printing by Fournier le Jeune FOURNIER TYPOGRAPHIQUE SPECIMEN Fournier Typographic Specimen �� LES CARACTERES DE L’IMPRIMERIE PAR FOURNIER LE JEUNE The characteres of Printing by Fournier le Jeune contents History of the Artist 7 The Point System 9 Casting the Letterform 13 Type Styles 15 Type in Use 21 Citation 23 history of the artist pierre-simon fournier his books Fournier le Jeune’s work was widely Sep. 15 1712 - 8 Oct. 1768 was a Author of Manuel Typographique, French mid-18th century punch two volumes published in 1764 and accepted during the Rococo period because cutter, typefounder and typographic 1766. The first volume is one of the theoretician. He was both a collector major source books on the processes of the elegant and sensual curves which he and originator of types. Fournier’s of making printing types in the era of contributions to printing were his the hand press. Volume two includes lent to his type and ornaments. creation of initials and ornaments, his a comprehensive specimen of the design of letters, and his standardiza- types and ornaments of Fournier's tion of type sizes. He worked in the own foundry, most of which he rococo form, and designed typefaces cut himself, and as such provides a including Fournier and Narcissus. record of one of the most remarkable He was known for incorporating personal achievements in the history “decorative typographic ornaments” of typefounding. into his typefaces. Fournier’s main accomplishment is that he “created a his typefaces standardized measuring system that The Fournier mt family by Monotype would revolutionize the typography was based on the types cut by Pierre- industry forever”. -

Font Folio 11 Content

Font Folio 11 Content OpenType CFF Fonts Adobe Preferred Menu Name File (PS) Name Aachen Std Bold AachenStd-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic AdobeArabic.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Bold ACaslonPro-Bold.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Bold Italic ACaslonPro-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Italic ACaslonPro-Italic.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Regular ACaslonPro-Regular.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Semibold ACaslonPro-Semibold.otf Adobe Caslon Pro Semibold Italic ACaslonPro-SemiboldItalic.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Bold AGaramondPro-Bold.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Bold Italic AGaramondPro-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Italic AGaramondPro-Italic.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Regular AGaramondPro-Regular.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Semibold AGaramondPro-Semibold.otf Adobe Garamond Pro Semibold Italic AGaramondPro-SemiboldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew AdobeHebrew.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold AJensonPro-Bold.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Caption AJensonPro-BoldCapt.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Display AJensonPro-BoldDisp.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Italic AJensonPro-BoldIt.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Italic Caption AJensonPro-BoldItCapt.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Italic Display AJensonPro-BoldItDisp.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Italic Subhead AJensonPro-BoldItSubh.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Bold Subhead AJensonPro-BoldSubh.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Caption AJensonPro-Capt.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Display AJensonPro-Disp.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Italic AJensonPro-It.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Italic Caption AJensonPro-ItCapt.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Italic Display AJensonPro-ItDisp.otf Adobe Jenson Pro Italic Subhead AJensonPro-ItSubh.otf Adobe Jenson Pro -

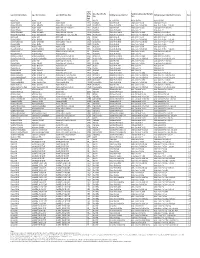

Mapping of Adobe's Type 1 Fonts to Opentype

Type 1 PC File Type 1 Mac Outline File Matching OpenType format Mac Menu Type 1 PostScript FontName Type 1 Mac Menu Name Type 1 Win/PC Menu Name Matching OpenType format font Matching OpenType format Win/PC Menu Name Notes Name Name Name Prefix Aachen-Bold Aachen Aachen ACB__ AacheBol AachenStd-Bold Aachen Std Bold Aachen Std Bold ACaslon-AltBold ACaslon AltBold ACaslon AltBold AWAB_ ACasAltBol ACaslonPro-Bold Adobe Caslon Pro Bold Adobe Caslon Pro Bold 2 ACaslon-AltBoldItalic ACaslon AltBoldItalic ACaslon AltBold + italic style AWABI ACasAltBolIta ACaslonPro-BoldItalic Adobe Caslon Pro Bold Italic Adobe Caslon Pro Bold + italic style 2 ACaslon-AltItalic ACaslon AltItalic ACaslon AltRegular + italic style AWAI_ ACasAltIta ACaslonPro-Italic Adobe Caslon Pro Italic Adobe Caslon Pro + italic style 2 ACaslon-AltRegular ACaslon AltRegular ACaslon AltRegular AWARG ACasAltReg ACaslonPro-Regular Adobe Caslon Pro Adobe Caslon Pro 2 ACaslon-AltSemibold ACaslon AltSemibold ACaslon AltRegular + bold style AWASB ACasAltSem ACaslonPro-Semibold Adobe Caslon Pro SmBd Adobe Caslon Pro + bold style 2 ACaslon-AltSemiboldItalic ACaslon AltSemiboldItalic ACaslon AltRegular + bold, italic styles AWASI ACasAltSemIta ACaslonPro-SemiboldItalic Adobe Caslon Pro SmBd Italic Adobe Caslon Pro + bold, italic styles 2 ACaslon-Bold ACaslon Bold ACaslon Bold AWB__ ACasBol ACaslonPro-Bold Adobe Caslon Pro Bold Adobe Caslon Pro Bold 1 ACaslon-BoldItalic ACaslon BoldItalic ACaslon Bold + bold style AWBI_ ACasBolIta ACaslonPro-BoldItalic Adobe Caslon Pro Bold Italic Adobe -

Capítulo 1. Historia De La Tipografía

Historia de la tipografía En este capítulo conoceremos el desarrollo de la tipogra- fía, desde Gutenberg, con la invención de los tipos móvi- les de metal, hasta la actualidad. Encontraremos informa- ción de tipógrafos, tipografías, innovaciones técnicas, fundiciones tipográficas y otros acontecimientos relevan- tes que ocurrieron durante estos 5 siglos y que además 1nos adentrarán en el universo de la tipografía. 1.1 Incunables: 1440-1500 Con la disponibilidad del papel, la impresión con bloques de madera tallada y la creciente demanda de libros, naciones como Italia, Alemania, Francia y los Países Bajos, buscaban la produc- ción de textos por medio de la mecanización utilizando tipos móviles. Alrededor de 1440, Johann Gensfleisch zum Gutenberg, desarrolló en Alemania una técnica para elaborar moldes de tipos que se utilizarían para la impresión de letras individuales (los chi- nos fueron los primeros en utilizar tipos móviles, hechos de made- ra, durante la primera mitad del siglo xi); escogió el tipo textura como modelo, imitando el trabajo de los escribas de la época, para que el nuevo estilo fuera aceptado. La obra más representa- tiva de Gutenberg es su Biblia de 42 líneas que desarrolló con esta técnica, la cual estuvo vigente por 500 años. Los tipos móviles 1 Retrato del s. xvi de la posible apariencia de Gutenberg (A. Thevet, Pourtraits et vies, 1584). Página de la Biblia de 42 líneas de Gutenberg. Las ilustraciones, así como algunos detalles en la composición del texto, fueron añadidas a mano después de haberse impreso. Este ejemplar se encuentra en la Biblioteca Británica en 2 Londres.