The Votive Scenario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7

Oral history interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Massimo Vignelli on 2011 June 6-7. The interview took place at Vignelli's home and office in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Mija Riedel has reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Massimo Vignelli in his New York City office on June 6, 2011, for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Good morning. Let's start with some of the early biographical information. We'll take care of that and move along. MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Okay. MIJA RIEDEL: You were born in Milan, in Italy, in 1931? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Nineteen thirty-one, a long time ago. MIJA RIEDEL: Okay. What was the date? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Actually, 80 years ago, January 10th. I'm a Capricorn. MIJA RIEDEL: January 10th. -

„Ihr Müsst Allen Bildern Den Abschied Geben

OF CHURCHES, HERETICS, AND OTHER GUIDES OF THE BLIND –'THE FALL OF THE BLIND LEADING THE BLIND' BY PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER AND THE ESTHETICS OF SUBVERSION – Jürgen Müller Heresy in Pictures Pictures are a medium of biblical exegesis. By illustrating biblical contents, they provide a specific interpretation of a particular passage, clarifying and disambiguating images even where the Scripture is vague or obscure. First of all, this is due to the nature of the texts in the Old and New Testaments, since it is indeed rare that the descriptions of events and persons are vivid enough for a painter to derive precise instructions regarding artistic composition from them. Pictures, however, are subject to the necessity of putting something in concrete form; therefore, they require legitimization and are part of orthodoxy, whatever it may be.1 Since the time of the Reformation at the very latest, pictures have been used as a means of religious canonization to give expression to orthodoxy, but also to denounce the respective opposing side, of course. But whatever their function in religious practice may have been, as a rule they represented instruments of disambiguation. Luther, in particular, valued pictures as a pedagogical tool and took a critical stance against the iconoclasts.2 For him, their essential purpose was to teach, simply and clearly.3 In the following remarks, I would like to explore the reverse case and present pictures as agents of subversion. For the interpreter this poses a task that does not involve certainty, but ambiguity or equivocality. For in this context, semantic ambivalence is not in any way an expression of a modern concept of art in the sense of Umberto Eco's Open Work; rather, it is due to the fact that a heterodox meaning is being hidden in the pictures. -

Preparing Images for Delivery

TECHNICAL PAPER Preparing Images for Delivery TABLE OF CONTENTS So, you’ve done a great job for your client. You’ve created a nice image that you both 2 How to prepare RGB files for CMYK agree meets the requirements of the layout. Now what do you do? You deliver it (so you 4 Soft proofing and gamut warning can bill it!). But, in this digital age, how you prepare an image for delivery can make or 13 Final image sizing break the final reproduction. Guess who will get the blame if the image’s reproduction is less than satisfactory? Do you even need to guess? 15 Image sharpening 19 Converting to CMYK What should photographers do to ensure that their images reproduce well in print? 21 What about providing RGB files? Take some precautions and learn the lingo so you can communicate, because a lack of crystal-clear communication is at the root of most every problem on press. 24 The proof 26 Marking your territory It should be no surprise that knowing what the client needs is a requirement of pro- 27 File formats for delivery fessional photographers. But does that mean a photographer in the digital age must become a prepress expert? Kind of—if only to know exactly what to supply your clients. 32 Check list for file delivery 32 Additional resources There are two perfectly legitimate approaches to the problem of supplying digital files for reproduction. One approach is to supply RGB files, and the other is to take responsibility for supplying CMYK files. Either approach is valid, each with positives and negatives. -

FTA First Guide

Design Guide An SPI Project DESIGN FLEXOGRAPHIC TECHNICAL ASSOCIATION FIRST 4.0 SUPPLEMENTAL FLEXOGRAPHIC PRINTING DESIGN GUIDE 1.0 Design Introduction 1 5.0 File Formats and Usage 30 1.1 Overview 2 5.1 Specified Formats 30 1.2 Responsibility 2 5.2 Portable Document Format (PDF) 30 1.3 Assumptions 3 5.3 Clip Art 31 5.4 Creating and Identifying FPO Continuous Tone Images 31 2.0 Getting Started 4 5.5 Special Effects 31 2.1 Recognizing Attributes of the Flexographic Process 4 5.6 Image Substitution – Automatic Image Replacement 32 2.2 Materials and Information Needed to Begin 5 5.7 File Transfer Recommendations 32 2.2.1 Template Layout / Die-Cut Specifications 55.8 Program Applications 32 2.3 File Naming Conventions 6 6.0 Preflight of Final Design Prior to Release 33 6 2.4 Types of Proofs 8 6.1 Documenting the Design 33 2.5 Process Control Test Elements 9 6.2 Release to Prepress 34 3.0 Type and Design Elements 9 3.1 Typography: Know the Print Process Capabilities 9 3.1.1 Registration Tolerance 12 3.1.2 Process Color Type 13 3.1.3 Process Reverse/Knockout 13 3.1.4 Line Reverse/Knockout 13 3.1.5 Drop Shadow 13 3.1.6 Spaces and Tabs 14 3.1.7 Text Wrap 14 3.1.8 Fonts 14 3.2 Custom and Special Colors 16 3.3 Bar Code Design Considerations 17 3.3.1 Bar Code Specifications 18 3.3.2 Designer Responsibilities 18 3.3.3 USPS Intelligent Mail Bar Code 22 3.4 Screen Ruling 22 3.5 Tints 23 3.6 Ink Colors 24 4.0 Document Structure 25 4.1 Naming Conventions 26 4.2 Document Size 26 4.3 Working in Layers 26 4.4 Auto-Traced / Revectorized Art 26 4.5 Blends, Vignettes, Gradations 27 4.6 Imported Images – Follow the Links 28 4.7 Electronic Whiteout 29 4.8 Image Capture Quality – Scanning Considerations 29 4.9 Scaling & Resizing 30 4.10 Color Space 30 FLEXOGRAPHIC IMAGE REPRODUCTION SPECIFICATIONS & TOLERANCES 1 DESIGN 1.0 DESIGN INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview FIRST 4.0 is created to facilitate communication among all participants involved in the design, preparation and printing of flexographic materials. -

Guide to Publishing at the US Department of Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 457 533 CS 510 669 AUTHOR Ohnemus, Edward; Zimmermann, Jacquelyn TITLE Guide to Publishing at the U.S. Department of Education. November 2001 Edition. INSTITUTION Department of Education, Washington, DC. Office of the Secretary.; Office of Public Affairs (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2001-11-00 NOTE 56p. AVAILABLE FROM ED Pubs, P.O. Box 1398, Jessup, MD 20794-1398. Tel: 877-433-7827 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ed.gov/pubs/edpubs.html. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Editing; *Federal Government; Guidelines; Layout (Publications); Printing; Speeches; *Writing for Publication ABSTRACT This guide is intended for use by United States Department of Education employees and contractors working on manuscripts to be published by all principal offices except for the Office of Educational Research and Improvement, which includes the National Center for Education Statistics. It helps authors publish according to the duties and responsibilities of the United States Department of Education, whose mission is to ensure equal access to education and to promote educational excellence throughout the nation. Sections of the guide are: Your First Steps toward Publishing; Who Should Use This Guide; How This Guide Will Help You; Why You Must Publish through Government Channels; Getting Your Manuscript Edited and Printed; Getting Your Manuscript Designed; Steps in a Typical Printing Job at ED; Parts of a Publication; Sample Verso (Boilerplate) Page; Verso Page Explanation; The Writing Guides to Use; Limits on Content; Publishing Translations of ED Publications; Publishing Newsletters; Stationery and Business Cards; Giving and Publishing Official Speeches; How Your Publication Will Reach the Audience for Whom It Was Intended; and Forms Needed To Get Your Manuscript Edited and Printed. -

The Fall of the Blind Leading the Blind by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and the Esthetics of Subversion*

OF CHURCHES, HERETICS, AND OTHER GUIDES OF THE BLIND: THE FALL OF THE BLIND LEADING THE BLIND BY PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER AND THE ESTHETICS OF SUBVERSION* Jürgen Müller Heresy in Pictures Pictures are a medium of biblical exegesis. By illustrating biblical sub jects, they provide a specific interpretation of selected passages, clarifying and disambiguating by means of images, even where Scripture is vague or obscure. This is due first of all to the nature of the texts in the Old and New Testaments: one rarely encounters descriptions of persons and events vivid enough to function as precise templates for pictorial compo sitions. Pictures, on the other hand, are subject to the necessity of putting something in concrete form; as such, they require legitimization and are potentially instruments of codification.1 During the Reformation pictures were used to canonize religious view points and to give expression to various orthodoxies, but also to denounce the heterodoxy of the opposing side. But whatever their function in reli gious practice may have been, as a rule they operated as vehicles of dis ambiguation. Luther, in particular, valued pictures as a pedagogical tool and took a critical stance against the iconoclasts.2 For him, their essential purpose was to teach, simply and clearly.3 * Translated from German to English by Rosemarie Greenman and edited by Walter Melion. 1 Cf. Scribner R.W., “Reformatorische Bildpropaganda”, Historische Bildkunde 12 (1991) 83–106. 2 Cf. Berns J.J., “Die Macht der äußeren und der inneren Bilder. Momente des innerpro testantischen Bilderstreits während der Reformation”, in Battafarano I.M. -

A Sketch of the History of Music-Printing, from the Fifteenth to The

A Sketch of the History of Music-Printing, from the Fifteenth to the Nineteenth Century ( Continued) Author(s): Friedrich Chrysander Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 18, No. 413 (Jul. 1, 1877), pp. 324-326 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3355495 Accessed: 17-01-2016 05:24 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.240.43.43 on Sun, 17 Jan 2016 05:24:14 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL 324 TIMES.--JuLY I, 1877. is only the shallow water that foams and rages. Judging him by this standard of his own, we must Farther out the "blue profound" merely rises in unfortunatelycancel a considerable part of his book. obedience to force and then sinks again to rest upon Poor Schmid! Too much learning often dulls the the spot from which it rose. So with the effect of spirit, if there is not on the other side a little his- fashion on a nation's music. -

HANS BALDUNG GRIEN En Alsace HANS BALDUNG GRIEN En Alsace a - Armoiries De La Famille Baldung (Vers 1530) LANGUE ET CULTURE RÉGIONALES CAHIER N°8

LANGUE ET CULTURE RÉGIONALES CAHIER N°8 HANS BALDUNG GRIEN en Alsace HANS BALDUNG GRIEN en Alsace a - Armoiries de la famille Baldung (vers 1530) LANGUE ET CULTURE RÉGIONALES CAHIER N°8 HANS BALDUNG GRIEN en Alsace pour le 500e anniversaire de sa naissance par Théodore Rieger réédition numérique en ligne, 2014 Cet ouvrage, édité par CANOPÉ académie de Strasbourg, à la demande de la Mission Académique aux Enseignements Régionaux et Internationaux de l’académie de Strasbourg, a bénéficié du concours financier des Conseils Généraux du Bas-Rhin et du Haut-Rhin et du Conseil Régional d’Alsace. Directeur de publication : Yves SCHNEIDER Coordination éditoriale : Jacques SPEYSER Infographies, mise en pages et adaptation numérique : Agnès GOESEL © CANOPÉ ACADÉMIE DE STRASBOURG ISSN : 0763-8604 ISBN (2014) : 978-2-86636-438-0 (ISBN : 2-86636-031-3, 1987) Dépôt légal : juillet 2014 LISTE DES illustrations Planches en couleurs A. Portrait de jeune homme à la fourrure ............................................................30 B. Saint Georges et saint Mathias ........................................................................31 C. Portrait du chanoine Ambroise Volmar Keller ..................................................32 D. La Vierge à la treille ........................................................................................33 E. L'Incrédulité de saint Thomas ..........................................................................34 F. Hercule étouffant Antée ..................................................................................35 -

FFTA FIRST 5.0 Design Guide (Pdf)

Complimentary Design Guide 5.0 Flexographic Image Reproduction Specifications & Tolerances Complimentary Design Guide An FTA Strategic Planning Initiative Project The Flexographic Technical Association has made this FIRST 5.0 supplement of the design guide available to you, and your design partners, as an enhancement to your creative process. To purchase the book in it’s entirety visit: www.flexography.org/first Copyright, © 1997, ©1999, ©2003, ©2009, ©2013, ©2014 by the Flexographic Technical Association, Inc. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953462 Edition 5.0 Published by the Flexographic Technical Association, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Inquires should be addressed to: FTA 3920 Veterans Memorial Hwy Ste 9 Bohemia NY 11716-1074 www.flexography.org International Standard Book Number ISBN-13: 978-0-9894374-4-8 Content Notes: 1. This reference guide is designed and formatted to facilitate ease of use. As such, pertinent information (including text, charts, and graphics) are repeated in the Communication and Implementation, Design, Prepress and Print sections. 2. Registered trademark products are identified for information purposes only. All products mentioned in this book are trademarks of their respective owner. The author and publisher assume no responsibility for the efficacy or performance. While every attempt has been made to ensure the details described in this book are accurate, the author and publisher assume no responsibility for any errors that may exist, or for any loss of data which may occur as a result of such errors. .1 ii Flexographic Image Reproduction Specifications & Tolerances 5.0 INTRODUCTION The Mission of FIRST FIRST seeks to understand customers’ graphic requirements for reproduction and translate those aesthetic requirements into specifications for each phase of the flexographic printing process including: customers, designers, prepress providers, raw material & equipment suppliers, and printers. -

Guidelines for Preparing and Submitting Electronic Design and Pre-Press Files Professional Graphics (Part 1) 427-033 Electronic Design 9/11/97 2:03 PM Page 1

427-033 Electronic Design 9/12/97 6:52 AM Page c1 U.S. Government Printing Office Publication 300.6 August 1997 Guidelines for Preparing and Submitting Electronic Design and Pre-Press Files Professional Graphics (Part 1) 427-033 Electronic Design 9/11/97 2:03 PM Page 1 To Our Customers, The United States Government Printing Office (GPO) is dedicated to providing our customers the best possible printed job at the lowest possible price, while meeting each customer’s deadline. To do this effec- tively, GPO must be able to provide usable Electronic Design and Pre-Press (EDPP) files to the printing contractor. Commonly referred to as Desktop Publishing, EDPP covers electronic publishing from design to press. The following guidelines will assist you in preparing effective EDPP files for items created using professional publish- ing software packages. Due to the many advantages of digital design, we encourage all of our customers to consider submitting jobs as digital copy on electronic media. Your assistance in following these guidelines is appreciated. MICHAEL F. DIMARIO Public Printer PG–1 427-033 Electronic Design 9/11/97 2:03 PM Page 2 Special Notes The EDPP guidelines are a two-part set dedi- cated to providing customers with valuable information about creating publications on a desktop computer. The section that you are currently reading is Part 1—Professional Graphics. If you are a customer who is currently using an Office Graphics (OG) application such as Word- Perfect, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Powerpoint, Microsoft Excel, Freelance Graphics, Microsoft Publisher or Harvard Graphics, please refer to Part 2—Office Graphics. -

Administrator's Guide

Oracle® Hyperion Financial Data Quality Management, Enterprise Edition Administrator's Guide Release 11.1.2.4.220 E73556-08 February 2019 Oracle Hyperion Financial Data Quality Management, Enterprise Edition Administrator's Guide, Release 11.1.2.4.220 E73556-08 Copyright © 2009, 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Primary Author: EPM Information Development Team This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency- specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. -

QP Prepress Form

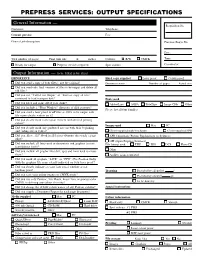

PREPRESS SERVICES: OUTPUT SPECIFICATIONS General Information — Requisition No. Customer: Telephone: Contact person: Fax: General job description: Previous Req’n No. Date: Total number of pages: Final trim size X inches Colours: Ⅺ B/W Ⅺ CMYK Time: Ⅺ Ready for output Ⅺ Prepress services required Spot colours: Coordinator: Output Information — to be filled in by client IMPORTANT: Hard copy supplied Ⅺ Laser proof Ⅺ Colour proof Ⅺ Did you send a copy of your file(s), not the original? Document name Number of pages Actual size Ⅺ Did you send only final versions of files to be output and delete all old files? Ⅺ Did you use ‘‘Collect for Output’’ or ‘‘Save-as, copy all files’’ command to load transport disk? Fonts used Ⅺ Did you label and name all of your disks? Ⅺ Adobe/Lino Ⅺ AGFA Ⅺ TrueType Ⅺ Image Club Ⅺ Other Ⅺ Did you include a ‘‘Print Window’’ directory of disk contents? Please list all font families Ⅺ Did you send a laser proof of all files at 100% to be output with file name clearly written on it? Ⅺ Did you clearly mark each layout element with desired printing colour? Images used Ⅺ Mac Ⅺ PC Ⅺ Did you clearly mark any graduated screens with their beginning and ending screen values? Ⅺ Client-supplied high-resolution Ⅺ Client-supplied FPO Ⅺ Did you allow .125Љ bleed in all layout elements that touch a page Ⅺ APR (Automatic Picture Replacement in SyQuest) edge? Ⅺ OPI (Open Prepress Interface) Ⅺ Did you include all fonts used in documents and graphics (screen File format used Ⅺ TIFF Ⅺ EPS Ⅺ DCS Ⅺ PhotoCD fonts/printer fonts)? Ⅺ Other Ⅺ Did you include all graphic files (tiff, eps) and fonts used to create them? Ⅺ Archive scans requested Ⅺ Did you mark all graphics ‘‘LIVE’’ or ‘‘FPO’’ (For Position Only) with the graphics file name clearly indicated on your laser proof? Ⅺ Did you clearly indicate on your laser proof whether or not keylines print? Trapping Ⅺ Provided by client࠽0.