Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garamond and the French Renaissance Garamond and the French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan for Everyone Ever

Garamond and The French Renaissance Garamond and The French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan For Everyone ever Design © 2014 Kylie Harrigan Garamond Typeface The French Renassaince Garamond, An Overview Garamond is a typeface that is widely used today. The namesake of that typeface was equally as popular as the typeface is now when he was around. Starting out as an apprentice punch cutter Claude Garamond 2 quickly made a name for himself in the typography industry. Even though the typeface named for Claude Garamond is not actually based on a design of his own it shows how much of an influence he was. He has his typefaces, typefaces named after him and typeface based on his original typefaces. As a major influence during the 16th century and continued influence all the way to today Claude Garamond has had a major influence in typography and design. Claude Garamond was born in Paris, France around 1480 or 1490. Rather quickly Garamond entered the industry of typography. He started out as an apprentice punch cutter and printer. Working for Antoine Augereau he specialized in type design as well as punching cutting and printing. Grec Du Roi Type The Renaissance in France It was under Francis 1, king of France The Francis 1 gallery in the Italy, including Benvenuto Cellini; he also from 1515 to 1547, that Renaissance art Chateau de Fontainebleau imported works of art from Italy. All this While artists and their patrons in France and and architecture first blossomed in France. rapidly galvanised a large part of the French the rest of Europe were still discovering and Shortly after coming to the throne, Francis, a Francis 1 not only encouraged the nobility into taking up the Italian style for developing the Gothic style, in Italy a new cultured and intelligent monarch, invited the Renaissance style of art in France, he their own building projects and artistic type of art, inspired by the Classical heritage, elderly Leonardo da Vinci to come and work also set about building fine Renaissance commissions. -

The Origins of the Underline As Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: a Case Study in Skeuomorphism

The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Romano, John J. 2016. The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797379 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism John J Romano A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Abstract This thesis investigates the process by which the underline came to be used as the default signifier of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web. Created in 1990 by Tim Berners- Lee, the web quickly became the most used hypertext system in the world, and most browsers default to indicating hyperlinks with an underline. To answer the question of why the underline was chosen over competing demarcation techniques, the thesis applies the methods of history of technology and sociology of technology. Before the invention of the web, the underline–also known as the vinculum–was used in many contexts in writing systems; collecting entities together to form a whole and ascribing additional meaning to the content. -

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Oral History Interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7

Oral history interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Massimo Vignelli on 2011 June 6-7. The interview took place at Vignelli's home and office in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Mija Riedel has reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Massimo Vignelli in his New York City office on June 6, 2011, for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Good morning. Let's start with some of the early biographical information. We'll take care of that and move along. MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Okay. MIJA RIEDEL: You were born in Milan, in Italy, in 1931? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Nineteen thirty-one, a long time ago. MIJA RIEDEL: Okay. What was the date? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Actually, 80 years ago, January 10th. I'm a Capricorn. MIJA RIEDEL: January 10th. -

Bluebook Citation in Scholarly Legal Writing

BLUEBOOK CITATION IN SCHOLARLY LEGAL WRITING © 2016 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. The writing assignments you receive in 1L Legal Research and Writing or Legal Practice are primarily practice-based documents such as memoranda and briefs, so your experience using the Bluebook as a first year student has likely been limited to the practitioner style of legal writing. When writing scholarly papers and for your law journal, however, you will need to use the Bluebook’s typeface conventions for law review articles. Although answers to all your citation questions can be found in the Bluebook itself, there are some key, but subtle differences between practitioner writing and scholarly writing you should be careful not to overlook. Your first encounter with law review-style citations will probably be the journal Write-On competition at the end of your first year. This guide may help you in the transition from providing Bluebook citations in court documents to doing the same for law review articles, with a focus on the sources that you are likely to encounter in the Write-On competition. 1. Typeface (Rule 2) Most law reviews use the same typeface style, which includes Ordinary Times New Roman, Italics, and SMALL CAPITALS. In court documents, use Ordinary Roman, Italics, and Underlining. Scholarly Writing In scholarly writing footnotes, use Ordinary Roman type for case names in full citations, including in citation sentences contained in footnotes. This typeface is also used in the main text of a document. Use Italics for the short form of case citations. Use Italics for article titles, introductory signals, procedural phrases in case names, and explanatory signals in citations. -

Visual Research Universal Communication Communication of Selling the Narrow Column Square Span Text in Color Change of Impact New Slaves

VISUAL RESEARCH UNIVERSAL COMMUNICATION COMMUNICATION OF SELLING THE NARROW COLUMN SQUARE SPAN TEXT IN COLOR CHANGE OF IMPACT NEW SLAVES ON TYPOGRAPHY by Herbert Bayer Typography is a service art, not a fine art, however pure and elemental the discipline may be. The graphic designer today seems to feel that the typographic means at his disposal have been exhausted. Accelerated by the speed of our time, a wish for new excitement is in the air. “New styles” are hopefully expected to appear. Nothing is more constructive than to look the facts in the face. What are they? The fact that nothing new has developed in recent decades? The boredom of the dead end without signs for a renewal? Or is it the realization that a forced change in search of a “new style” can only bring superficial gain? It seems appropriate at this point to recall the essence of statements made by progressive typographers of the 1920s: Previously used largely as a medium for making language visible, typographic material was discovered to have distinctive optical properties of its own, pointing toward specifically typographic expression. Typographers envisioned possibilities of deeper visual experiences from a new exploitation of the typographic material itself. Typography was for the first time seen not as an isolated discipline and technique, but in context with the ever-widening visual experiences that the picture symbol, photo, film, and television brought. They called for clarity, conciseness, precision; for more articulation, contrast, tension in the color and black and white values of the typographic page. They recognized that in all human endeavors a technology had adjusted to man’s demands; while no marked change or improvement had taken place in man’s most profound invention, printing-writing, since Gutenberg. -

X Garamond & His Famous Types

x Garamond & His Famous Types HENRY LEWIS BULLEN Ahistor y very interesting to all who may be benefited through the use of printing. t is a par t of the glory of French artthat two type designs that areadmittedly masterpieces beyond competition werecreated byFrench- men. These creations havehad a decisiveinflu- ence on subsequent type designers, and though four hundred and fifty years havepassed since the first use of one of these designs, and three hundred and seventy- fivesince the first use of the other,both of them in their original models arenow morepopular and moregenerally used than in any previous period. The earliest of these master designers was Nicolas Jenson, who first used his famous Roman types in Venice in 1470.But we are heremoreconcerned with the second master,Claude Gara- mond of Paris, in whose honor this book is issued and in reproduc- tions of whose famous Roman and Italic type designs it is composed, that those who read herein may better understand their merits. Original steel punches and copper matrices made and used by Garamond, some time beforehis death in 1561,are now the proper ty of the French nation, and areincluded as an item in the great asset of the national arts which French governments, whether royal, imperial or republican in form, haveinvariably honoured and protected. These implements and the types cast bymeans of them arekept in a special ‘Garamond & His Famous Types’ was originally published in An Exhibit of Garamond Type with Appropriate Ornaments. Being the third of a series of books showing the many beautiful types in the composing room of Redfield- Kendrick-Odell Co., Printers & Map Makers (Redfield-Kendrick-Odell Co.: Ne w York, 1927). -

A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 11-1-1992 A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P. Wall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Wall, David P., "A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology" (1992). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of David P. Wall With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of DECEMBER 1992 Da,e Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator George H. Ryan Direcmr or Designa[e A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology by David P. Wall A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology November 1992 Project Advisor: Professor David Pankow Introduction type,' When Adobe Systems introduced in 1990 their first digital library of 'wood the event marked the latest step forward in a tradition dating back to 1828, when Darius Wells, ofNew Wells' York City, perfected the equipment and techniques needed to mass produce wood type. -

Smooth Writing with In-Line Formatting Louise S

NESUG 2007 Posters Smooth Writing with In-Line Formatting Louise S. Hadden, Abt Associates Inc., Cambridge, MA ABSTRACT PROC TEMPLATE and ODS provide SAS® programmers with the tools to create customized reports and tables that can be used multiple times, for multiple projects. For ad hoc reporting or the exploratory or design phase of creating custom reports and tables, SAS® provides us with an easy option: in-line formatting. There will be a greater range of in-line formatting available in SAS 9.2, but the technique is still useful today in SAS versions 8.2 and 9.1, in a variety of procedures and output destinations. Several examples of in-line formatting will be presented, including formatting titles, footnotes and specific cells, bolding specified lines, shading specified lines, and publishing with a custom font. INTRODUCTION In-line formatting within procedural output is generally limited to three procedures: PROC PRINT, PROC REPORT and PROC TABULATE. The exception to this rule is in-line formatting with the use of ODS ESCAPECHAR, which will be briefly discussed in this paper. Even without the use of ODSESCAPECHAR, the number of options with in- line formatting is still exciting and almost overwhelming. As I was preparing to write this paper, I found that I kept thinking of more ways to customize output than would be possible to explore at any given time. The scope of the paper therefore will be limited to a few examples outputting to two destination “families”, ODS PRINTER (RTF and PDF) and ODS HTML (HTML4). The examples presented are produced using SAS 9.1.3 (SP4) on a Microsoft XP operating system. -

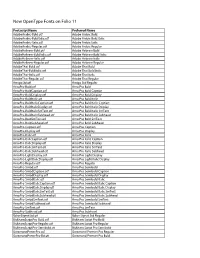

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Patrick Reagh Printers Note: the Number Following the Name Indicates the Monotype Series

Monotype typefaces available for fonts and composition at Patrick Reagh Printers note: the number following the name indicates the Monotype series. An e or an a after the number indicates either English- or American-manufactured matrices. R-roman / I-italic / SC-small caps / B-boldface lc-large composition* Antique 26a R 8 10 12 Baskerville 353a R/I/SC 7 8 10 11 12 Bembo 270e R/I/SC 8 10 11 12 13 14 (16 & 18 lc R/I) Narrow Bembo Italic 194e 10 12 13 (16 lc) Bodoni Medium 375a R/I/SC 8 10 12 Bodoni Book 875a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Bookman 98a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Bulmer 462a R/I/SC 6 8 9 10 12 (18 lc R) Centaur 252a (16 lc roman only) Cochin 61a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Deepdene 315a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Ehrhardt 453e R/I/SC 10 12 14 Fournier 185e R/I/SC 10 12 13 Franklin Gothic 107a R 6 8 10 12 Futura Light 606a R/I 6 8 10 12 Futura Medium /Extra Bold 605a & 603a R 6 8 10 12 Garamont 248a R/I/SC 8 10 12 Garamond Bold 548a R/I 6 8 10 12 Gill Sans 262e R/I/B 6 7 8 10 12 Goudy Bold 294a R/I 8 10 12 Goudy Modern 249e R/I/SC 8 10 11 12 Goudy Old Style 394a R/I/SC 6 8 10 12 Janson 401a R/I/SC 8 9 10 11 12 (14 & 18 lc R/I) Jenson Old Style 58a R 8 10 12 Sans Serif 329a (Kabel) R/B 8 10 12 Sans Serif Light/Bold 329a & 330a R 8 10 12 Univers Light 45e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Medium 55e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Bold 65e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 Univers Extra Bold 75e R/I 6 8 10 12 14 *Large composition can only be composed in roman or italic separately 1 Monotype display typefaces available for fonts at Patrick Reagh Printers note: the letter d following the size on English matrices indicates Didot which is the European standard for type sizing and is generally a point or two larger than the American point system.