Investing in Urban Sustainable Development in Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounds of War and Peace: Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945

10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. Exploiting to the full methodologies and research tools developed in the fields of sound and soundscape studies, the Sounds of War and Peace authors analyse their reflections on autobiographical texts and art. The studies demonstrate the role urban sounds played in the inhabitants’ forging a sense of 1945 Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945 identity as they adapted to new living conditions. The chapters also shed light on the ideological forces at work in the creation of urban sound space. Sounds of War and Peace. War Sounds of Soundscapes of European Cities in Volume 10 Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Renata Tańczuk is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Sławomir Wieczorek is a faculty member of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) · Wieczorek / Sławomir Tańczuk Renata ISBN 978-3-631-75336-1 EESM 10_275336_Wieczorek_SG_A5HC globalL.indd 1 16.04.18 14:11 10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. -

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

Arkusz RADZYMIN (488)

PAŃSTWOWY INSTYTUT GEOLOGICZNY PAŃSTWOWY INSTYTUT BADAWCZY OPRACOWANIE ZAMÓWIONE PRZEZ MINISTRA ŚRODOWISKA OBJAŚNIENIA DO MAPY GEOŚRODOWISKOWEJ POLSKI 1:50 000 Arkusz RADZYMIN (488) Warszawa 2010 Autorzy: Sławomir Mądry*, Paweł Kwecko***, Hanna Tomassi- Morawiec***, Krystyna Wojciechowska** Główny koordynator MGśP: Małgorzata Sikorska-Maykowska*** Redaktor regionalny planszy A: Katarzyna Strzemińska*** Redaktor regionalny planszy B: Joanna Szyborska-Kaszycka *** Redaktor tekstu: Sylwia Tarwid-Maciejowska.*** * - Przedsiębiorstwo Usług Geologicznych „Kielkart”, ul. Starowapiennikowa 6, 25-113 Kielce ** - Przedsiębiorstwo Geologiczne „Polgeol” SA, ul. Berezyńska 39, 03-908 Warszawa *** - Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny, ul. Rakowiecka 4, 00-975 Warszawa ISBN ………………. Copyright by PIG and MŚ, Warszawa 2010 Spis treści I. Wstęp (Sławomir Mądry) ............................................................................................................. 3 II. Charakterystyka geograficzna i gospodarcza (Sławomir Mądry) ............................................. 4 III. Budowa geologiczna (Sławomir Mądry) .................................................................................. 7 IV. Złoża kopalin (Sławomir Mądry) ............................................................................................ 10 1. Surowce ilaste ceramiki budowlanej ................................................................................ 10 2. Piaski kwarcowe .............................................................................................................. -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

S Y L a B U S

S Y L A B U S Course: CODE: Informatization of Civil Procedure Faculty: Wydział Prawa i Administracji (Faculty of Law and Administration) Form of Ye Semester Form of Course Hours the Exam ECTS ar 2021/2022 2 lecture 1 test 3 5 Teacher dr Karolina Ziemianin The Aims of the The aim of the course is to familiarize the student with the IT aspects of civil procedure. They cover in Course particular the issues of using IT tools during the trial and in the administration of justice. Prerequisites The student should have basic knowledge of substantive and procedural civil law. TEACHING EFFECT’S Category The effect’s descritpion KNOWLEDGE The student knows and distinguishes computer tools that are being used in the judicial and extrajudicial proceedings. The students knows the types of judicial and extrajudicial proceedings in the computer tools are used. The student typifies tasks of the judicial authorities in the field of creating and using computer tools in the jurisdiction. SKILLS The student solves problems described in simple cases. The student is able to properly use the available computers tools used in the judicial and extrajudicial proceedings. The student is able to prepare applications and pleadings in the proceedings that use computers tools. COMPETENCES The student is ready to undertake individual and team activities related to the administration of justice. The student is ready to identify with the tasks carried out in the practice of law with the use of tools to inform the administration of justice. STUDY CONTENT 1. Introduction to civil procedure – basic issues. 1 2. -

Poli Sh Genealogcal Soci Ettq of Mlrfiesota Newsletteiili

Poli sh Genealogcal Soci ettq of MlrfiesotA NEWSLETTEIili VOLI.JME 13 WIMER 2005-06 NUMBBR 4 A Survivor's Guide to Finding Ancestors in Poland: My experience in researching the M AG DZI ARZ| LAB AK fami I i e s from Pilzno, Galicia through Chicago to Sturgeon Lake, MN By Mark Dobosenski [email protected]> All of us have had to start somewhere in our search for nm our ancestors originating in Poland--but where do we begin? this issue " . " How does one go about this grurd scavenger hunt? WtritE A Survivor's Guide to Finding there are many rcsources available online and in printed form Ancestors in Poland......................p. 1 (some of which will be noted for you ro try), I thought it might be helpful to document my search for my wife's ancestors. President's Letter........ ........2 I used to ask many questions of my father-in-law, fhe late The Bulletin Board............................... 3 Frank MAGDZIARZ, of Sturgeon Lake, MN. Sometime Letters to the editor........ .......................4 after Dianne and I were married and I became interested in Where is ?inovrocwa? qagTg both my and my wife's family hisrories. Maybe having Pommem? Pomorze? Kaszuby? children brought that urge to mind? Nonetheless, Frank had a great mind for relationships! Group Tour to Poland.......................5 Marcinkiewicz of Little Falls Well, the first step in beginning one's family history re- DNA Genealogy search is to ask questions: check with living family members Polish Churches of the Archdiocese of and record your information down in eithera notebook or St. -

Geographischer Index

2 Gerhard-Mercator-Universität Duisburg FB 1 – Jüdische Studien DFG-Projekt "Rabbinat" Prof. Dr. Michael Brocke Carsten Wilke Geographischer und quellenkundlicher Index zur Geschichte der Rabbinate im deutschen Sprachgebiet 1780-1918 mit Beiträgen von Andreas Brämer Duisburg, im Juni 1999 3 Als Dokumente zur äußeren Organisation des Rabbinats besitzen wir aus den meisten deutschen Staaten des 19. Jahrhunderts weder statistische Aufstellungen noch ein zusammenhängendes offizielles Aktenkorpus, wie es für Frankreich etwa in den Archiven des Zentralkonsistoriums vorliegt; die For- schungslage stellt sich als ein fragmentarisches Mosaik von Lokalgeschichten dar. Es braucht nun nicht eigens betont zu werden, daß in Ermangelung einer auch nur ungefähren Vorstellung von Anzahl, geo- graphischer Verteilung und Rechtstatus der Rabbinate das historische Wissen schwerlich über isolierte Detailkenntnisse hinausgelangen kann. Für die im Rahmen des DFG-Projekts durchgeführten Studien erwies es sich deswegen als erforderlich, zur Rabbinatsgeschichte im umfassenden deutschen Kontext einen Index zu erstellen, der möglichst vielfältige Daten zu den folgenden Rubriken erfassen soll: 1. gesetzliche, administrative und organisatorische Rahmenbedingungen der rabbinischen Amts- ausübung in den Einzelstaaten, 2. Anzahl, Sitz und territoriale Zuständigkeit der Rabbinate unter Berücksichtigung der histori- schen Veränderungen, 3. Reihenfolge der jeweiligen Titulare mit Lebens- und Amtsdaten, 4. juristische und historische Sekundärliteratur, 5. erhaltenes Aktenmaterial -

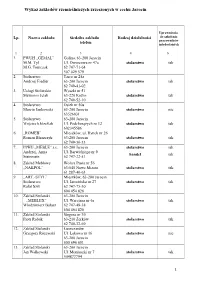

Wykaz Zakładów Rzemieślniczych Zrzeszonych W Cechu Jarocin

Wykaz zakładów rzemie ślniczych zrzeszonych w cechu Jarocin Uprawnienia Lp. Nazwa zakładu Siedziba zakładu Rodzaj działalno ści do szkolenia pracowników telefon młodocianych 1 2 3 4 6 1. PWUH „GEMAL” Golina, 63-200 Jarocin M.M. Tyl Ul. Dworcowa nr 47a stolarstwo tak M.G. Tomczak 62 747-71-64 507 029 579 2. Stolarstwo Tarce nr 25a Andrzej Fiedler 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-41-02 3. Usługi Stolarskie Wyszki nr 51 Sławomir Jelak 63-220 Kotlin stolarstwo tak 62 740-52-10 4. Stolarstwo Osiek nr 50a Marcin Jankowski 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo nie 63526031 5. Stolarstwo 63-200 Jarocin Wojciech Józefiak Ul. Podchor ąż ych nr 12 stolarstwo tak 602345586 6. „ROMEB” Mieszków, ul. Rynek nr 26 Roman Błaszczyk 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-30-33 7. PPHU „MEBLE” s.c. 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak Andrzej, Anna Ul. Barwickiego nr 9 handel tak Steinmetz 62 747-22-51 8. Zakład Meblowy Wolica Pusta nr 56 „NAKPOL” 63-040 Nowe Miasto stolarstwo tak 61 287-40-63 9. „ART.-STYL” Mieszków, 63-200 Jarocin Stolarstwo Ul. Jaroci ńska nr 27 stolarstwo tak Rafał Szik 62 747-75-50 604 454 826 10. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin „MEBLEX” Ul. Warciana nr 6a stolarstwo tak Włodzimierz Bałasz 62 747-48-38 604 454 826 11. Zakład Stolarski St ęgosz nr 30 Piotr Robak 63-210 Żerków stolarstwo tak 62 740-32-69 12. Zakład Stolarski Łuszczanów Grzegorz Ró żewski Ul. Ł ąkowa nr 16 stolarstwo nie 63-200 Jarocin 600 696 651 13. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin Jan Wałkowski Ul. -

INFORMATOR O Jednostkach Nieodpłatnego Poradnictwa Dostępnego Dla Mieszkańców Powiatu Wołomińskiego.Pdf

o jednostkach nieodpłatnego poradnictwa dostępnego dla mieszkańców powiatu wołomińskiego INFORMATOR www.powiat-wolominski.pl Lista jednostek nieodpłatnego poradnictwa zawiera dane jednostek nieod- 1. PORADNICTWO RODZINNE płatnego poradnictwa uporządkowane według tematyki poradnictwa, w tym Zakres poradnictwa: jednostek publicznych, jednostek niepublicznych działających na zlecenie Poradnictwo rodzinne obejmuje problemy funkcjonowania rodziny, w tym opieki nad osobą niepełnosprawną a także oraz jednostek prowadzących działalność pożytku publicznego działających terapię rodzinną. na zlecenie, którym powierzono zadania z zakresu poradnictwa specjalistycz- Kryterium dostępu: nego na podstawie odrębnych przepisów. Dane obejmują informacje o zakre- Osoby i rodziny, które mają trudności lub wykazują potrze- bę wsparcia w rozwiązywaniu swoich problemów życio- sie poradnictwa, kryteriach dostępu do usługi, nazwie jednostek, adresach wych, bez względu na posiadany dochód. i danych kontaktowych, w tym stronach internetowych i numerach telefonów, Jednostka dniach i godzinach działalności oraz kryteria dostępu do usługi. Adres Dni i godziny dyżurów Telefon, e-mail, www prowadząca Gminny Ośrodek ul. T. Kościuszki 14, • poniedziałek: 9.00 – 18.00 29 757-80-85 Lista zawiera także wykaz krajowych infolinii tematycznych i innych form Pomocy Społecznej 05-252 Dąbrówka • wtorek – czwartek: 7.30 – 15.30 731-907-002 porad świadczonych za pośrednictwem komunikacji elektronicznej jako form • piątek: 7.30 – 14.30 [email protected] www.bip.dabrowka.net.pl poradnictwa również łatwo dostępnego dla mieszkańców powiatu – podane jako ostatnie w danej kategorii tematycznej. Gminny Ośrodek ul. Jana Pawła II 17, • poniedziałek, wtorek, czwartek: 25 675-41-09 Pomocy Społecznej 05-280 Jadów 8.00 – 16.00 [email protected] • środa: 7.00 – 17.00 www.jadow.az.pl od strony • piątek: 8.00 – 14.00 podwórka (w piątek nie przyjmuje się inte- SPIS TRESCI resantów w sprawie świadczeń 1. -

Uchwała Nr XXIX/208/2017 Z Dnia 30 Marca 2017 R

DZIENNIK URZĘDOWY WOJEWÓDZTWA WIELKOPOLSKIEGO Poznań, dnia 5 kwietnia 2017 r. Poz. 2837 UCHWAŁA NR XXIX/208/2017 RADY GMINY DOMINOWO z dnia 30 marca 2017 r. w sprawie dostosowania sieci szkół podstawowych i gimnazjum do nowego ustroju szkolnego. Na podstawie art. 18 ust. 2 pkt 15 ustawy z dnia 8 marca 1990r. o samorządzie gminnym (Dz. U. 2016 r., poz. 446 ze zmianami) oraz art. 210 ustawy z dnia 14 grudnia 2016 r. Przepisy wprowadzające ustawę – Prawo oświatowe (Dz.U. 2017 r. poz. 60) uchwala się, co następuje: § 1. Uchwała określa: 1) plan sieci publicznych szkół podstawowych prowadzonych przez Gminę Dominowo, a także granice obwodów publicznych szkół podstawowych prowadzonych przez Gminę Dominowo na okres od dnia 1 września 2017 roku do dnia 31 sierpnia 2019 roku, który stanowi załącznik nr 1 do niniejszej uchwały; 2) plan sieci prowadzonego przez Gminę Dominowo gimnazjum oraz granice obwodu dotychczasowego gimnazjum prowadzonego przez Gminę Dominowo na okres od dnia 1 września 2017 roku do dnia 31 sierpnia 2019 roku, który stanowi załącznik nr 2 do niniejszej uchwały; 3) plan sieci publicznych ośmioletnich szkół podstawowych prowadzonych przez gminę, a także granice obwodów publicznych ośmioletnich szkół podstawowych prowadzonych przez Gminę Dominowo, od dnia 1 września 2019 roku, który stanowi załącznik nr 3 do niniejszej uchwały. § 2. Gimnazjum w Gieczu im. mjr Henryka Sucharskiego z siedzibą w Gieczu, przekształca się w ośmioletnia szkołę podstawową: 1) nazwa szkoły ; Szkoła Podstawowa w Gieczu; 2) siedziba szkoły: Giecz 25, 63-012 Dominowo ; 3) dzień rozpoczęcia działalności szkoły: 1 września 2017 roku; 4) rok szkolny, w którym rozpocznie się kształcenie w klasie pierwszej: 2019/2020. -

L392 Official Journal

Official Journal L 392 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Legislation 23 November 2020 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/1737 of 14 July 2020 amending Regulation (EC) No 273/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Regulation (EC) No 111/2005 as regards the inclusion of certain drug precursors in the list of scheduled substances (1) . 1 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1738 of 16 November 2020 approving non- minor amendments to the specification for a name entered in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications (‘Asparago verde di Altedo’ (PGI)) . 8 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1739 of 20 November 2020 amending and correcting Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/761 as regards the quantities available for tariff rate quotas for certain agricultural products included in the WTO schedule of the Union following the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the Union, a tariff quota for poultrymeat originating in Ukraine and a tariff quota for meat of bovine animals originating in Canada . 9 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1740 of 20 November 2020 setting out the provisions necessary for the implementation of the renewal procedure for active substances, as provided for in Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 844/2012 (1) . 20 DECISIONS ★ Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1741 of 20 November 2020 amending the Annex to Implementing Decision 2014/709/EU concerning animal health control measures relating to African swine fever in certain Member States (notified under document C(2020) 8266) (1) . -

Harmonogram Wywozu Odpadów Komunalnych Z Gminy I Miasta Jastrowie - Rok 2021” Zabudowa Jednorodzinna, Aktualizacja Ważna Od 01.07.2021”

ul. Wojska Polskiego 29, 64-915 Jastrowie, WWW.ZECIUK.PL Tel./fax 672662809, e-mail [email protected] „HARMONOGRAM WYWOZU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH Z GMINY I MIASTA JASTROWIE - ROK 2021” ZABUDOWA JEDNORODZINNA, AKTUALIZACJA WAŻNA OD 01.07.2021” MIEJSCOWOŚĆ HARMONOGRAM NA ODBIÓR ZMIESZANYCH ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH Styczeń Luty Marzec Kwiecień Maj Czerwiec Lipiec Sierpień Wrzesień Październik Listopad Grudzień Jastrowie ul.: Wojska Polskiego, Urocza, Przemysłowa, Wywóz odbywał się będzie co dwa tygodnie: WTOREK Kwiatowa, Ogrodowa, Miła, Brzozowa, Narutowicza, Świętojańska, Zaułek Świętoj., Słoneczna, Grunwaldzka, Mickiewicza, Kościelna, Kilińszczaków, Kilińskiego, Kolejowa, 5, 19 2, 16 2, 16, 30 13, 27 11, 25 8, 22 6, 20 3, 17, 31 14, 28 12, 26 9, 23 7, 21 Poznańska, Jagiellońska, Cmentarna, Roosevelta, Dworcowa, Graniczna, Jeziorna, Polna i okoliczne nieujęte Jastrowie - Hajda, Jastrowie - Byszki, Samborsko, Brzeźnica, Wywóz odbywał się będzie co dwa tygodnie: ŚRODA Sypniewo, Budy, Smolary, Trzebieszki, Prądy, Piaski, Zagórze, 13, 27 10, 24 10, 24 7, 21 5, 19 2, 16, 30 7, 21 4, 18 1, 15, 29 13, 27 10, 24 8, 22 Jastrowie ul. Kilińszczaków „za torami” Nadarzyce, Brzeźnica Kolonia, Sypniewko, Wywóz odbywał się będzie co dwa tygodnie: CZWARTEK Sypniewko Folwark, Sypniewo Kolonia 14, 28 11, 25 11, 25 8, 22 6, 20 4 (piątek), 17 1, 15, 29 12, 26 9, 23 7, 21 4, 18 2, 16, 30 Wywóz odbywał się będzie co dwa tygodnie: PIĄTEK Jastrowie ul.: Wądołek, Gdańska, Konopnicka, Słowackiego, 1 Maja, al. Wolności, Poniatowskiego, 10 Pułku Piechoty, 2 Lutego, Inwalidów,