Paradowska.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounds of War and Peace: Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945

10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. Exploiting to the full methodologies and research tools developed in the fields of sound and soundscape studies, the Sounds of War and Peace authors analyse their reflections on autobiographical texts and art. The studies demonstrate the role urban sounds played in the inhabitants’ forging a sense of 1945 Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945 identity as they adapted to new living conditions. The chapters also shed light on the ideological forces at work in the creation of urban sound space. Sounds of War and Peace. War Sounds of Soundscapes of European Cities in Volume 10 Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Renata Tańczuk is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Sławomir Wieczorek is a faculty member of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) · Wieczorek / Sławomir Tańczuk Renata ISBN 978-3-631-75336-1 EESM 10_275336_Wieczorek_SG_A5HC globalL.indd 1 16.04.18 14:11 10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany

Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany This book is about the ethics of nursing and midwifery, and how these were abrogated during the Nazi era. Nurses and midwives actively killed their patients, many of whom were disabled children and infants and patients with mental (and other) illnesses or intellectual disabilities. The book gives the facts as well as theoretical perspectives as a lens through which these crimes can be viewed. It also provides a way to teach this history to nursing and midwifery students, and, for the first time, explains the role of one of the world’s most historically prominent midwifery leaders in the Nazi crimes. Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Susan Benedict is Professor of Nursing, Director of Global Health, and Co- Director of the Campus-Wide Ethics Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing in Houston. Linda Shields is Professor of Nursing—Tropical Health at James Cook Uni- versity, Townsville, Queensland, and Honorary Professor, School of Medi- cine, The University of Queensland. Routledge Studies in Modern European History 1 Facing Fascism 9 The Russian Revolution of 1905 The Conservative Party and the Centenary Perspectives European dictators 1935–1940 Edited by Anthony Heywood and Nick Crowson Jonathan D. Smele 2 French Foreign and Defence 10 Weimar Cities Policy, 1918–1940 The Challenge of Urban The Decline and Fall of a Great Modernity in Germany Power John Bingham Edited by Robert Boyce 11 The Nazi Party and the German 3 Britain and the Problem of Foreign Office International Disarmament Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Arthur 1919–1934 L. -

Lilo Linke a 'Spirit of Insubordination' Autobiography As Emancipatory

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ autobiography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/177/ Version: Full Version Citation: Ogurla, Anita Judith (2016) Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ auto- biography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Lilo Linke: A ‘Spirit of Insubordination’ Autobiography as Emancipatory Pedagogy; A Turkish Case Study Anita Judith Ogurlu Humanities & Cultural Studies Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, February 2016 I hereby declare that the thesis is my own work. Anita Judith Ogurlu 16 February 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines the life and work of a little-known interwar period German writer Lilo Linke. Documenting individual and social evolution across three continents, her self-reflexive and autobiographical narratives are like conversations with readers in the hope of facilitating progressive change. With little tertiary education, as a self-fashioned practitioner prior to the emergence of cultural studies, Linke’s everyday experiences constitute ‘experiential learning’ (John Dewey). Rejecting her Nazi-leaning family, through ‘fortunate encounter[s]’ (Goethe) she became critical of Weimar and cultivated hope by imagining and working to become a better person, what Ernst Bloch called Vor-Schein. Linke’s ‘instinct of workmanship’, ‘parental bent’ and ‘idle curiosity’ was grounded in her inherent ‘spirit of insubordination’, terms borrowed from Thorstein Veblen. -

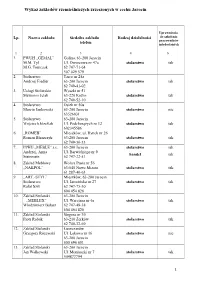

Wykaz Zakładów Rzemieślniczych Zrzeszonych W Cechu Jarocin

Wykaz zakładów rzemie ślniczych zrzeszonych w cechu Jarocin Uprawnienia Lp. Nazwa zakładu Siedziba zakładu Rodzaj działalno ści do szkolenia pracowników telefon młodocianych 1 2 3 4 6 1. PWUH „GEMAL” Golina, 63-200 Jarocin M.M. Tyl Ul. Dworcowa nr 47a stolarstwo tak M.G. Tomczak 62 747-71-64 507 029 579 2. Stolarstwo Tarce nr 25a Andrzej Fiedler 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-41-02 3. Usługi Stolarskie Wyszki nr 51 Sławomir Jelak 63-220 Kotlin stolarstwo tak 62 740-52-10 4. Stolarstwo Osiek nr 50a Marcin Jankowski 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo nie 63526031 5. Stolarstwo 63-200 Jarocin Wojciech Józefiak Ul. Podchor ąż ych nr 12 stolarstwo tak 602345586 6. „ROMEB” Mieszków, ul. Rynek nr 26 Roman Błaszczyk 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-30-33 7. PPHU „MEBLE” s.c. 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak Andrzej, Anna Ul. Barwickiego nr 9 handel tak Steinmetz 62 747-22-51 8. Zakład Meblowy Wolica Pusta nr 56 „NAKPOL” 63-040 Nowe Miasto stolarstwo tak 61 287-40-63 9. „ART.-STYL” Mieszków, 63-200 Jarocin Stolarstwo Ul. Jaroci ńska nr 27 stolarstwo tak Rafał Szik 62 747-75-50 604 454 826 10. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin „MEBLEX” Ul. Warciana nr 6a stolarstwo tak Włodzimierz Bałasz 62 747-48-38 604 454 826 11. Zakład Stolarski St ęgosz nr 30 Piotr Robak 63-210 Żerków stolarstwo tak 62 740-32-69 12. Zakład Stolarski Łuszczanów Grzegorz Ró żewski Ul. Ł ąkowa nr 16 stolarstwo nie 63-200 Jarocin 600 696 651 13. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin Jan Wałkowski Ul. -

Arani, Miriam Y. "Photojournalism As a Means of Deception in Nazi-Occupied Poland, 1939– 45." Visual Histories of Occupation: a Transcultural Dialogue

Arani, Miriam Y. "Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939– 45." Visual Histories of Occupation: A Transcultural Dialogue. Ed. Jeremy E. Taylor. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 159–182. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350167513.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 13:56 UTC. Copyright © Jeremy E. Taylor 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939–45 Miriam Y. Arani Introduction Outside Europe, the conflicting memories of Germans, Poles and Jews are hard to understand. They are informed by conflicts before and during the Second World War. In particular, the impact of Nazism in occupied Poland (1939–45) – including the Holocaust – is difficult to understand without considering the deceitful propaganda of Nazism that affected visual culture in a subliminal but crucial way. The aim of this chapter is to understand photographs of the Nazi occupation of Poland as visual artefacts with distinct meanings for their contemporaries in the framework of a specific historical and cultural context. I will discuss how Nazi propaganda deliberately exploited the faith in still photography as a neutral depiction of reality, and the extent of that deceit through photojournalism by the Nazi occupiers of Poland. In addition, I will outline methods through which to evaluate the reliability of photographic sources. For the purposes of reliability and validity, I use a large, randomized sample with all kinds of photographs from archives, libraries and museums in this study. -

Poles Under German Occupation the Situation and Attitudes of Poles During the German Occupation

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/poles-under-german-occu/15596,Poles-under-German-Occupation.html 2021-09-25, 22:48 Poles under German Occupation The Situation and Attitudes of Poles during the German Occupation The Polish population found itself in a very difficult situation during the very first days of the war, both in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in The General Government. The policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Executions, resettlements, arrests, deportations to camps, and street round-ups were a constant element of the everyday life of Poles during the war. Initially the policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Food rationing was imposed in cities and towns, with food coupons covering about one-third of a person’s daily needs. Levies — obligatory, regular deliveries of selected produce — were introduced in the countryside. Farmers who failed to deliver their levy were subject to severe repressions, including the death penalty. Devaluation and difficulty with finding employment were the reason for most Poles’ poverty and for the everyday problems in obtaining basic products. The occupier also limited access to healthcare. The birthrate fell dramatically while the incidence of infectious diseases increased significantly. -

The Employment Effects of Immigration: Evidence from the Mass Arrival of German Expellees in Post-War Germany

The Employment Effects of Immigration: Evidence from the Mass Arrival of German Expellees in Post-war Germany By Sebastian Braun and Toman Omar Mahmoud No. 1725| August 2011 Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Hindenburgufer 66, 24105 Kiel, Germany Kiel Working Paper No. 1725 | August 2011 The Employment Effects of Immigration: Evidence from the Mass Arrival of German Expellees in Post-war Germany* Sebastian Braun and Toman Omar Mahmoud Abstract: This paper studies the employment effects of the influx of millions of German expellees to West Germany after World War II. The expellees were forced to relocate to post-war Germany. They represented a complete cross-section of society, were close substitutes to the native West German population, and were very unevenly distributed across labor market segments in West Germany. We find a substantial negative effect of expellee inflows on native employment. The effect was, however, limited to labor market segments with very high inflow rates. IV regressions that exploit variation in geographical proximity and in pre-war occupations confirm the OLS results. Keywords: Forced migration, native employment, post-war Germany JEL classification: J61, J21, C36 Sebastian Braun Kiel Institute for the World Economy Telephone: +49 431 8814 482 E-mail: [email protected] Toman Omar Mahmoud Kiel Institute for the World Economy Telephone: +49 431 8814 471 E-mail: [email protected] * We thank Eckhardt Bode, Michael C. Burda, Michael Kvasnicka, Alexandra Spitz-Oener, Andreas Steinmayr, Nikolaus Wolf and participants of research seminars in Berlin and Kiel for helpful comments and discussions. Martin Müller-Gürtler and Richard Franke provided excellent research assistance. -

OBWIESZCZENIE Powiatowej Komisji Wyborczej W Jarocinie Z Dnia 2 Października 2018 R

OBWIESZCZENIE Powiatowej Komisji Wyborczej w Jarocinie z dnia 2 października 2018 r. o zarejestrowanych listach kandydatów na radnych w wyborach do Rady Powiatu Jarocińskiego zarządzonych na dzień 21 października 2018 r. Na podstawie art. 435 § 1 w związku z art. 450 ustawy z dnia 5 stycznia 2011 r. - Kodeks wyborczy (Dz. U. z 2018 r. poz. 754, 1000 i 1349) Powiatowa Komisja Wyborcza w Jarocinie podaje do wiadomości publicznej informację o zarejestrowanych listach kandydatów na radnych w wyborach do Rady Powiatu Jarocińskiego zarządzonych na dzień 21 października 2018 r. Okręg wyborczy Nr 1 Okręg wyborczy Nr 2 Okręg wyborczy Nr 3 Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL Lista nr 2 - KOMITET WYBORCZY PSL 1. KOŁODZIEJ Ryszard Idzi, lat 72, zam. Zakrzew 1. WŁODARCZYK Bronisława Kazimiera, lat 76, zam. 1. JĘDRASZCZYK Jacek Marek, lat 70, zam. Żerków 2. MATUSZAK Karol Piotr, lat 54, zam. Golina Jarocin 2. SZLACHETKA Andrzej, lat 34, zam. Komorze 3. IGNASIAK Katarzyna, lat 34, zam. Potarzyca 2. SZATKOWSKA Hanna Jadwiga, lat 51, zam. Jarocin Przybysławskie 4. PIECHOCKA Anita Magdalena, lat 34, zam. Cząszczew 3. FLORCZYK Wojciech Zdzisław, lat 66, zam. Jarocin 3. RYBACKA Agnieszka, lat 43, zam. Żerków 5. KOWNACKI Witold, lat 62, zam. Witaszyce 4. WALCZAK-GŁĄB Aleksandra, lat 60, zam. Jarocin 4. NOWAK Halina Maria, lat 64, zam. Szczonów 6. ORPEL Bartłomiej, lat 29, zam. Siedlemin 5. GROCHOWSKI Marek Jan, lat 66, zam. Jarocin 5. BIERNACIK Zbigniew, lat 49, zam. Chrzan 7. STASZAK Anna, lat 34, zam. Jarocin 6. FRANKIEWICZ Błażej, lat 54, zam. Jarocin 8. MĄKA Joanna, lat 23, zam. -

German Research Strategies and Sources for Eastern Provinces: Pomerania, Posen, Brandenburg, West Prussia, East Prussia, Silesia

German Research Strategies and Sources for Eastern Provinces: Pomerania, Posen, Brandenburg, West Prussia, East Prussia, Silesia Careen Barrett-Valentine, AG® ALWAYS START WITH GAZETTEERS • www.meyersgaz.org Digitized Meyer’s gazetteer online o German Empire jurisdictions are at the top of the entry page. o Click on map to see historical map. Click on “Toggle Historical Map” to see modern map. o Tutorial available soon www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/”How_to”_Guides_for_International_Research • www.kartenmeister.com Gazetteer of German Empire locations not in modern Germany. o Scroll downenter “German City Name”Choose entry o Modern Polish province name provided. Use GoogleMaps for other Polish jurisdictions. o Note “Lutheran Parish”, “Catholic Parish”, and “Civil Registry”. GENERAL RESOURCES: These resources should be used for research in all of the eastern provinces. • www.familysearch.org Germany records databases o “Search””Records”Click on Europe on the mapChoose “Germany” o Read list of “Indexed Historical Records” AND “Image Only Historical Records” o Browse ALL databases. Indexes are sometimes incomplete and always only as good as the indexer. • www.baza.archiwa.gov.pl/sezam/pradziad.php?l=en The PRADZIAD Database o Enter locality”Search”Scroll down”more” o Note dates, record type, and archive. Use GoogleTranslate for “remarks”. • www.szukajwarchiwach.pl Polish “Archival resources online” o Search for digitized and non-digitized records o Tutorial, www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Poland_”How_to”_Guides “Polish State Archives Online” • www.lostshoebox.com “Online Records for Poland” o Right side“Countries””Online Records for Poland” o The map shows you which websites to use. The list below the map describes the websites. -

Wykaz Kół Łowieckich Na Terenie Powiatu Jarocin

Wykaz kół łowieckich na terenie powiatu Jarocin numer miejscowości przynależne do powiat gmina koło łowieckie adres korespondencyjny mail Prezes Koła obwodu obwodu łowieckiego Jaraczewo, Łobez, Góra, K.Ł. Nr 27 "OSTOJA" Jaraczewo Łukaszewo 6, 63-233 Jaraczewo 411 Zalesie, Panienka, Niedźwiady, [email protected] Ryszard Maluśki Gola, Wojciechowo, Łobzowiec Aleksandrów, Wolica Pusta, K.Ł. Nr 48 "RYŚ" Poznań ul. Sasankowa 19, 62-002 Złotniki 317 Stramnice, Szypłów, Chwalęcin, Adam Feldmann Kolniczki, Komorze, Rogusko ul. Stefana Batorego 16, 63-200 K.Ł. Nr 28 "JELEŃ" Jarocin 415 Nosków, Porzęczew [email protected] Witold Kownacki Jarocin Jaraczewo K.Ł. Nr 76 "KNIEJA" Książ Wlkp. Grzymysław 28/4, 63-100 Śrem 326 Niedźwiady [email protected] Maciej Tempski Rusko, Strzyżewko, Ławęcice, K.Ł. Nr 21 "RUDEL" Rusko ul. Szkolna 10, 63-233 Jaraczewo 414 Poręba, Cerkwoca Stara, [email protected] Józef Bandyk Cerekwica Nowa, Parzęczew W.K.Ł. Nr 418 "WIDOWA" ul. Inwestycyjna 3, 55-040 417 Niedzwiady, Gola, Łukaszewo Jan Bartoszewicz Wrocław Kobierzyce K.Ł. Nr 82 "JELEŃ" Poznań ul. Bolkowicka 19, 60-301 Poznań 466 Suchorzewko, Rusko Mariusz Krzyżaniak ul. Wojska Polskiego 71d, 60-625 K.Ł. Nr 7 "PRZYLESIE" Poznań 412 Brzostów Wojciech Wesoły Poznań ul. Stefana Batorego 16, 63-200 K.Ł. Nr 28 "JELEŃ" Jarocin 415 Siedlemin, Potarzyca, Roszków [email protected] Witold Kownacki Jarocin Jarocin jarociński Leśniczówka Murzynówko 9, 63-023 K.Ł. Nr 77 "JELEŃ" Nowe Miasto 410 Radlin, Wilkowyja [email protected] Maciej Becela Sulęcinek Sierszew, Sucha, Żegocin, Wieczyn, Broniszewice, Żbiki, Grab, Pieruchy, Pieruszyczki, 398 Czermin, Robaków, Łęgi, Psienie Ostrów, Skrzypnia, K.Ł. -

Protection of Minorities in Upper Silesia

[Distributed to the Council.] Official No. : C-422. I 932 - I- Geneva, May 30th, 1932. LEAGUE OF NATIONS PROTECTION OF MINORITIES IN UPPER SILESIA PETITION FROM THE “ASSOCIATION OF POLES IN GERMANY”, SECTION I, OF OPPELN, CONCERNING THE SITUATION OF THE POLISH MINORITY IN GERMAN UPPER SILESIA Note by the Secretary-General. In accordance with the procedure established for petitions addressed to the Council of the League of Nations under Article 147 of the Germano-Polish Convention of May 15th, 1922, concerning Upper Silesia, the Secretary-General forwarded this petition with twenty appendices, on December 21st, 1931, to the German Government for its observations. A fter having obtained from the Acting-President of the Council an extension of the time limit fixed for the presentation of its observations, the German Government forwarded them in a letter dated March 30th, 1932, accompanied by twenty-nine appendices. The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate, for the consideration of the Council, the petition and the observations of the German Government with their respective appendices. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page I Petition from the “Association of Poles in Germany”, Section I, of Oppeln, con cerning the Situation of the Polish Minority in German Upper Silesia . 5 A ppendices to th e P e t i t i o n ................................................................................................................... 20 II. O bservations of th e G erm an G o v e r n m e n t.................................................................................... 9^ A ppendices to th e O b s e r v a t i o n s ...............................................................................................................I03 S. A N. 400 (F.) 230 (A.) 5/32.