Principles of Generative Phonology: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vowel Quality and Phonological Projection

i Vowel Quality and Phonological Pro jection Marc van Oostendorp PhD Thesis Tilburg University September Acknowledgements The following p eople have help ed me prepare and write this dissertation John Alderete Elena Anagnostop oulou Sjef Barbiers Outi BatEl Dorothee Beermann Clemens Bennink Adams Bo domo Geert Bo oij Hans Bro ekhuis Norb ert Corver Martine Dhondt Ruud and Henny Dhondt Jo e Emonds Dicky Gilb ers Janet Grijzenhout Carlos Gussenhoven Gert jan Hakkenb erg Marco Haverkort Lars Hellan Ben Hermans Bart Holle brandse Hannekevan Ho of Angeliek van Hout Ro eland van Hout Harry van der Hulst Riny Huybregts Rene Kager HansPeter Kolb Emiel Krah mer David Leblanc Winnie Lechner Klarien van der Linde John Mc Carthy Dominique Nouveau Rolf Noyer Jaap and Hannyvan Oosten dorp Paola Monachesi Krisztina Polgardi Alan Prince Curt Rice Henk van Riemsdijk Iggy Ro ca Sam Rosenthall Grazyna Rowicka Lisa Selkirk Chris Sijtsma Craig Thiersch MiekeTrommelen Rub en van der Vijver Janneke Visser Riet Vos Jero en van de Weijer Wim Zonneveld Iwant to thank them all They have made the past four years for what it was the most interesting and happiest p erio d in mylife until now ii Contents Intro duction The Headedness of Syllables The Headedness Hyp othesis HH Theoretical Background Syllable Structure Feature geometry Sp ecication and Undersp ecicati on Skeletal tier Mo del of the grammar Optimality Theory Data Organisation of the thesis Chapter Chapter -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Vowel Acoustics Reliably Differentiate Three Coronal Stops of Wubuy Across Prosodic Contexts

Vowel acoustics reliably differentiate three coronal stops of Wubuy across prosodic contexts Rikke L. BundgaaRd-nieLsena, BRett J. BakeRb, ChRistian kRoosa, MaRk haRveyc and CatheRine t. Besta,d aMARCS Auditory Laboratories, University of Western Sydney bSchool of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne cSchool of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle dHaskins Laboratories, New Haven Abstract The present study investigates the acoustic differentiation of three coronal stops in the indigenous Australian language Wubuy. We test independent claims that only VC (vowel-into-consonant) transitions provide robust acoustic cues for retroflex as compared to alveolar and dental coronal stops, with no differentiating cues among these three coronal stops evident in CV (consonant-into-vowel) transitions. The four-way stop distinction /t, t̪ , ʈ, c/ in Wubuy is contrastive word-initially (Heath 1984) and by implication utterance-initially, i.e., in CV-only contexts, which suggests that acoustic differentiation should be expected to occur in the CV transitions of this language, including in initial positions. Therefore, we examined both VC and CV formant transition information in the three target coronal stops across VCV (word-internal), V#CV (word-initial but utterance-medial) and ##CV (word- and utterance-initial), for /a / vowel contexts, which provide the optimal environment for investigating formant transitions. Results confirm that these coro- nal contrasts are maintained in the CVs in this vowel context, and in all three posi- tions. The patterns of acoustic differences across the three syllable contexts also provide some support for a systematic role of prosodic boundaries in influencing the degree of coronal stop differentiation evident in the vowel formant transitions. -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta*

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta* Michael Kenstowicz Massachusetts Institute of Technology Omaggio a P-M. Bertinetto Ogni toscano si comporta di fronte a una parola a lui nuova, come si nota p. es. nella lettura del latino, scegliendo costantamente, e inconsciamente, il timbro aperto, secondo il principio che il Migliorini ha condensato nella formula «vocale incerta, vocale aperta»…è il processo a cui vien sottoposto ogni vocabolo importato o adattato da altri linguaggi. (Franceschi 1965:1-3) 1. Introduction Standard Italian distinguishes seven vowels in stressed nonfinal syllables. The open ɛ,ɔ vs. closed e,o mid-vowel contrast (transcribed here as open è,ò vs. closed é,ó) is neutralized in unstressed position (1). (1) 3 sg. infinitive tócca toccàre ‘touch’ blòcca bloccàre ‘block’ péla pelàre ‘pluck’ * A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the MIT Phonology Circle and the 40th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, University of Washington (March 2010). Thanks to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments as well as to Maria Giavazzi, Giovanna Marotta, Joan Mascaró, Andrea Moro, and Mario Saltarelli. 1 gèla gelàre ‘freeze’ The literature uniformly identifies the unstressed vowels as closed. Consequently, the open è and ò have more restricted distribution and hence by traditional criteria would be identified as "marked" (Krämer 2009). In this paper we examine various lines of evidence indicating that the open vowels are optimal in stressed (open) syllables (the rafforzamento of Nespor 1993) and thus that the closed é and ó are "marked" in this position: {è,ò} > {é,ó} (where > means “better than” in the Optimality Theoretic sense). -

UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Strengthening, Weakening and Variability: The Articulatory Correlates of Hypo- and Hyper- articulation in the Production of English Dental Fricatives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hw2719n Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 14(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Melguy, Yevgeniy Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.5070/P7141042482 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2018) Yevgeniy Melguy Susan Lin, Brian Smith M.A. Qualifying Paper 9 December 2018 Strengthening, weakening and variability: The articulatory correlates of hypo- and hyper- articulation in the production of English dental fricatives 1. INTRODUCTION A number of influential approaches to understanding phonetic and phonological variation in speech have highlighted the importance of functional factors (Blevins, 2004; Donegan & Stampe, 1979; Kiparsky, 1988; Kirchner, 1998; Lindblom, 1990). Under such approaches, speaker- and listener-oriented principles—ease of articulation vs. perceptual clarity—often work in opposite directions with respect to consonantal articulation. Minimization of effort is thought to drive a general “weakening” of consonants (resulting in decreased articulatory constriction and/or duration) which often makes them more articulatorily similar to surrounding sounds. This can result in assimilation, lenition, and ultimately deletion, and generally comes at the expense of clarity. By contrast, maximization of clarity drives consonantal “strengthening” processes (resulting in increased articulatory constriction and/or duration) that makes target segments more distinct from neighboring sounds, which can result in fortition. Clear speech generally involves more extreme or “forceful” articulations, and usually comes at the expense of requiring more articulatory effort from the speaker. -

For the Third Case. Fairly Detailed Phonetic and Distributional Data Are Also Utilized

nof:J1611tNT nmsohlw ED 030 098 AL 001 858 By-Moskowitz, Arlene I. The Two-Year -Old Stage in the Acquisition of English Phonology. Spons Agency-American Cuunoi of Learned Societies, New Yofk, N.Y.; Social Science Research Council, Washington, D.C. Pub Date 29 Dec 68 Note-24p.. Slightly expanded verzion of i. paper presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, New York City, December 29, 1968. EDRS Price MF-1025 HC-$1.30 Descriptors -*Child Language, Consonants, Distinctive Features, Early Childhood, Enghsh. Language Development, Language Learning Levels, Language Patterns, Language Typology, Phonemes. Phonetic Analysis. ePhonogi,gy, Vowels The phonologies of three English-speaking children at approximately two years of age are examined. Two of the analyses are based on pOblished:studies. the third is based on observations and recordings made by the author. Summary statements on phonemic inventories and on correspondences with the adult model are presented. For the third case. fairly detailed phonetic and distributional data are also utilized. The paper attempts to draw conclusions about typical difficulties of phonological development at this stage and possible strategies used by children in attaining the adult norms. (Author/JD) . r U.S. DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION TINS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM DIE PERSON OR 016ANIZATION 0116INATIN6 IT.POINTS Of VIEW OR OPINIONS STAB DO NOT IIKESSAMLY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFRCEOf EDUCATION POSITION OR POUCY. TR TWO*TIAMOLD SUM IN Mg ACQUISITION orMUSHPHOMOLO0Y1 Arlen* I. Noskovitz AL 001858 0. Introduction. It is a widely held view among linguists and paycholinguists that the phonology of a child's speech at any 2 ilage during the acquisition process is structured. -

A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language Michelle Arden San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arden, Michelle, "A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language" (2010). Master's Theses. 3744. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.v36r-dk3u https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Linguistics and Language Development San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Michelle J. Arden May 2010 © 2010 Michelle J. Arden ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Daniel Silverman Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Soteria Svorou Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Kenneth VanBik Department of Linguistics and Language Development ABSTRACT A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden This thesis presents a linguistic analysis of the Mara language, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in northwest Myanmar and in neighboring districts of India. -

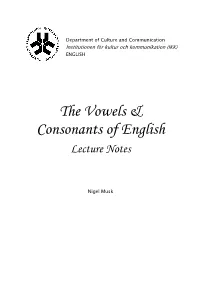

The Vowels & Consonants of English

Department of Culture and Communication Institutionen för kultur och kommunikation (IKK) ENGLISH The Vowels & Consonants of English Lecture Notes Nigel Musk The Consonants of English - - - Velar (Post Labio dental Palato Dental Palatal Glottal Bilabial alveolar alveolar) Alveolar Unvoiced (-V) -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V Voiced (+V) Stops (Plosives) p b t d k g ʔ1 Fricatives f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ h Affricates ʧ ʤ Nasals m n ŋ Lateral (approximants) l Approximants w2 r j w2 The consonants in the table above are the consonant phonemes of RP (Received Pronunciation) and GA (General American), that is, the meaning-distinguishing consonant sounds (c.f. pat – bat). Phonemes are written within slashes //, e.g. /t/. Significant variations are explained in the footnotes. /p/ put, supper, lip /ʃ/ show, washing, cash /b/ bit, ruby, pub /ʒ/ leisure, vision 3 /t/ two, letter , cat /h/ home, ahead 3 /d/ deep, ladder , read /ʧ/ chair, nature, watch /k/ can, lucky, sick /ʤ/ jump, pigeon, bridge /g/ gate, tiger, dog /m/ man, drummer, comb /f/ fine, coffee, leaf /n/ no, runner, pin /v/ van, over, move /ŋ/ young, singer 4 /θ/ think, both /l/ let , silly, fall /ð/ the, brother, smooth /r/ run, carry, (GA car) /s/ soup, fussy, less /j/ you, yes /z/ zoo, busy, use /w/ woman, way 1 [ʔ] is not regarded as a phoneme of standard English, but it is common in many varieties of British English (including contemporary RP), e.g. watch [wɒʔʧ], since [sɪnʔs], meet them [ˈmiːʔðəm]. -

The Sound Patterns of Camuno: Description and Explanation in Evolutionary Phonology

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Sound Patterns Of Camuno: Description And Explanation In Evolutionary Phonology Michela Cresci Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/191 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY by MICHELA CRESCI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City Universtiy of New York 2014 i 2014 MICHELA CRESCI All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS ____________________ __________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO ____________________ ___________________________________ Date Executive Officer KATHLEEN CURRIE HALL DOUGLAS H. WHALEN GIOVANNI BONFADINI Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY By Michela Cresci Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins This dissertation presents a linguistic study of the sound patterns of Camuno framed within Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins, 2004, 2006, to appear). Camuno is a variety of Eastern Lombard, a Romance language of northern Italy, spoken in Valcamonica. Camuno is not a local variety of Italian, but a sister of Italian, a local divergent development of the Latin originally spoken in Italy (Maiden & Perry, 1997, p. -

The Kortlandt Effect

The Kortlandt Effect Research Master Linguistics thesis by Pascale Eskes Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts July 2020 Supervisor: Dr. Alwin Kloekhorst Second reader: Prof. dr. Alexander Lubotsky ii Abstract It has been observed that pre-PIE *d sometimes turns into PIE *h₁, also referred to as the Kortlandt effect, but much is still unclear about the occurrence and nature of this change. In this thesis, I provide an elaborate discussion aimed at establishing the conditions and a phonetic explanation for the development. All words that have thus far been proposed as instances of the *d > *h₁ change will be investigated more closely, leading to the conclusion that the Kortlandt effect is a type of debuccalisation due to dental dissimilation when *d is followed by a consonant. Typological parallels for this type of change, as well as evidence from IE daughter languages, enable us to identify it as a shift from pre-glottalised voiceless stop to glottal stop. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Alwin Kloekhorst for guiding me through the writing process, helping me along when I got stuck and for his general encouragement. I also want to thank the LUCL lecturers for sharing their knowledge all these years and helping me identify and research my own linguistic interests; my family for their love and support throughout this project; my friends – with a special mention of Bahuvrīhi: Laura, Lotte and Vera – and Martin, also for their love and support, for the good times in between writing and for being willing to give elaborate advice on even the smallest research issues. -

Bftrkeley and LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE and BELIEFS

SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BFtRKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 UNIvERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUJBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY EDITORS (Los ANGELES): RALTPH L. BEALS, FRANEKLN FEARING, HARRY HOIJER Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 Submitted by editors September 30, 1943 Issued January 19, 1945 Price, 75 cents UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERIOA CONTENTS PAGE I. INTTRODUCTION ........................ .......................... 177 II. STORIIES 1. The Origin of Maize .................................................. 191 2. The Origin of Maize (Second Version) ....................... 196 3. Two Men Meet a Rayo .................................................. 196 4. Story of the Armadillo .................................................. 198 5. Why the Alligator Has No Tongue ......................... 199 6. How the Turkey Lost His Means of Defense . .................... 199 7. Origin of the Partridge .................................................. 199 8. Why Copal Is Burned for the Chanekos ....................... 200 9. An Encounter with Chanekos ............................................. 201 10. The Chaneko, The Man, His Mistress,