Lissencephaly Gene (LISI) Expression in the CNS Suggests a Role in Neuronal Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myotonic Dystrophies: Diagnosis and Management Chris Turner,1 David Hilton-Jones2

Review J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158261 on 22 February 2010. Downloaded from The myotonic dystrophies: diagnosis and management Chris Turner,1 David Hilton-Jones2 1Department of Neurology, ABSTRACT asymptomatic relatives as well as prenatal and National Hospital for Neurology There are currently two clinically and molecularly defined preimplantation diagnosis can also be performed.7 and Neurosurgery, London, UK 2Department of Clinical forms of myotonic dystrophy: (1) myotonic dystrophy Neurology, The Radcliffe type 1 (DM1), also known as ‘Steinert’s disease’; and Anticipation Infirmary, Oxford, UK (2) myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2), also known as DMPK alleles greater than 37 CTG repeats in length proximal myotonic myopathy. DM1 and DM2 are are unstable and may expand in length during meiosis Correspondence to progressive multisystem genetic disorders with several and mitosis. Children of a parent with DM1 may Dr C Turner, Department of Neurology, National Hospital for clinical and genetic features in common. DM1 is the most inherit repeat lengths considerably longer than those Neurology and Neurosurgery, common form of adult onset muscular dystrophy whereas present in the transmitting parent. This phenomenon Queen Square, London WC1N DM2 tends to have a milder phenotype with later onset of causes ‘anticipation’, which is the occurrence of 3BG, UK; symptoms and is rarer than DM1. This review will focus increasing disease severity and decreasing age of onset [email protected] on the clinical features, diagnosis and management of in successive generations. The presence of a larger Received 1 December 2008 DM1 and DM2 and will briefly discuss the recent repeat leads to earlier onset and more severe disease Accepted 18 December 2008 advances in the understanding of the molecular and causes the more severe phenotype of ‘congenital’ pathogenesis of these diseases with particular reference DM1 (figure 2).8 9 A child with congenital DM 1 to new treatments using gene therapy. -

X-Linked Myotubular Myopathy and Chylothorax

ARTICLE IN PRESS Neuromuscular Disorders xxx (2007) xxx–xxx www.elsevier.com/locate/nmd Case report X-linked myotubular myopathy and chylothorax Koenraad Smets * Department of Neonatology, Ghent University Hospital, De Pintelaan 185, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Received 10 August 2007; received in revised form 4 October 2007; accepted 24 October 2007 Abstract X-linked myotubular myopathy usually presents at birth with hypotonia and respiratory distress. Phenotypic presentation, however, can be extreme variable. We report on a newborn baby, who presented with the severe form of the disease. In the second week of life, he developed a clinically relevant chylothorax, needing drainage and treatment with octreotide acetate. Pleural effusions are frequently described in patients with congenital myotonic dystrophy. To our knowledge, the association of chylothorax and X-linked myotubular myopathy has not been described to date. As chylothorax could not be attributed to any evident condition in this child, perhaps it may be added to the clinical spectrum of X-linked myotubular myopathy. Ó 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: X-linked myotubular myopathy; Chylothorax 1. Introduction drainage (Fig. 1). Laboratory examination was compatible with chylothorax (5230 white blood cells/ll, 98% lympho- Congenital myopathies often present with hypotonia cytes; chylomicrons were present; triglycerides 746 mg/dl). and respiratory distress from birth, although their expres- There were no central venous catheters in place who could sion may be delayed. In most cases muscle biopsy is war- have caused thrombosis, impairing lymphatic flow, neither ranted for definitive diagnosis. In some instances could any other risk factor for chylothorax be identified. -

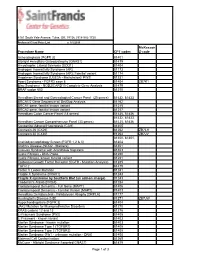

Procedure Name CPT Codes Mckesson Z-Code Achondroplasia

6161 South Yale Avenue, Tulsa, OK, 74136 | 918-502-1720 Preferred Client Price List v. 1/1/2019 McKesson Procedure Name CPT codes Z-code Achondroplasia {FGFR 3} 81401 Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy {GNAS1} 81479 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis {SOD1} 81404 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome {AR} 81173 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome {AR}; Familial variant 81174 Angelman Syndrome {UBE3A - Methylation}/ PWS 81331 Apert Syndrome - FGFR2 exon 8 81404 ZB7K1 Blau Syndrome - NOD2/CARD15 Complete Gene Analysis 81479 BRAF codon 600 81210 Hereditary Breast and Gynecological Cancer Panel (25 genes) 81432, 81433 BRCA1/2 Gene Sequence w/ Del/Dup Analysis 81162 BRCA1 gene, familial known variant 81215 BRCA2 gene, familial known variant 81217 Hereditary Colon Cancer Panel (18 genes) 81435, 81436 81432, 81433, Hereditary Cancer Comprehensive Panel (33 genes) 81435, 81436 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia {CAH} 81405 Connexin 26 {CX26} 81252 ZB7LH Connexin 30 {CX30} 81254 ZB7JV 81400, 81401, Craniodysmorphology Screen {FGFR 1,2 & 3} 81404 Crohn's Disease {NOD2 - Markers} 81401 Crouzon Syndrome with Acanthosis Nigricans 81403 Cystic Fibrosis - DNA Probe 81220 Cystic Fibrosis, known familial variant 81221 Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor {EGFR - Mutation Analysis} 81235 FGFR 2 81479 Factor V Leiden Mutation 81241 Fragile X Syndrome {FRAX1} 81243 Fragile X syndrome by Southern Blot (an add-on charge) 81243 Friederich's Ataxia {FRDA} 81284 Frontotemporal Dementia - Full Gene (MAPT) 81406 Frontotemporal Dementia - Familial Variant (MAPT) 81403 Hereditary Dentatorubral -

Why Do We Get New Families with Myotonic Dystrophy?

5 to 20 mutation 5 This mutation event probably only occurred once in human evolution in the shared common ancestor of 13 all Myotonic Dystrophy families. 11 12 14 15 20 to 35 20 repeats Repeats in this 5 to 15 repeats range are not 21 Repeats in this range associated with any are not associated symptoms and are 22 with any symptoms present at quite and are present at high frequency high frequency in the in the general 23 general population. population. They are They are genetically genetically unstable 24 very stable when when transmit- transmitted chang- ted, but increase in ing only very rarely. length quite slowly. 25 There is essen- There is definite tially zero risk of new risk of new Myo- 27 Myotonic Dystrophy tonic Dystrophy families arising from families arising from individuals with such individuals with such 30 repeats. repeats, but it may take many hundreds 33 of generations. 40 to 50 repeats 35 Repeats in this range are not associated with any symptoms, but are present at only very 40 low frequencies in the general population. They are though genetically unstable when transmitted, increasing in length very rapidly 45 and leading to new Myotonic Dystrophy families within a few generations. 50 60 to 3000 repeats 80 Repeats in this range are associated directly with Myotonic Dystrophy symptoms. The repeat is genetically very unstable and expands 300 rapidly in sucessive generations giving rise to the increased severity and decreased age of onset 1000 observed in Myotonic Dystrophy families. Myotonic Dystrophy Support Group Helpline 0115 987 0080 Myotonic dystrophy affects a wide range of body systems and varies dramatically in the relative severity of the symptoms and the age at which the first symptoms appear. -

Swallowing Diff Iculties in Myotonic Dystrophy

Swallowing Diff iculties in Myotonic Dystrophy by Jodi Allen Specialist Speech & Language Therapist, The National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery, London Swallowing difficulties are an important aspect of Myotonic Dystrophy due to potentially serious complications. They should be identified early to help reduce risk of life-threatening complications. Management options often include swallowing strategies and sometimes alternative routes of feeding. These will be outlined as part of this booklet. Brief Summary • Myotonic Dystrophy can affect the muscles of your face, mouth and throat. • Weakness or stiffness (myotonia) in these muscles can cause problems with swallowing. • Swallowing problems can lead to weight loss and chest infections. • Problems can be identified early by looking out for signs and symptoms. These may include longer mealtimes, food sticking in the throat, needing to drink with meals and coughing and spluttering. Myotonic Dystrophy Support Group Helpline 0115 987 0080 • Swallowing problems should be assessed by a Speech and Language Therapist who can provide you with tailored advice and options. How do we normally eat and drink? The wind pipe (known as the trachea) and food pipe (known as the oesophagus) sit very close together in the throat, as shown below. The airway and food pipe sit close together in the throat When talking or engaging in an activity other than eating and drinking, the airway is open. This allows oxygen to pass into the lungs and expel waste gases out. At these times the entrance to the food pipe is closed. At regular intervals we initiate ‘a swallow.’ This allows saliva to move from the mouth into the food pipe. -

Beyond Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes; Why Correct Diabetes Classification Is Important Gabriel I. Uwaifo, MD Dept of Endocrinology

Beyond Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes; Why Correct Diabetes Classification is Important Gabriel I. Uwaifo, MD, FACP, FTOS, FACE. Dept of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Weight Management, Ochsner Medical Center Objectives To highlight various classification methods of diabetes To highlight the importance and consequences of appropriate diabetes classification To provide suggested processes for diabetes classification in primary care settings and indices for specialty referral Presentation outline 1. Case presentations 2. Diabetes classification; past present and future 3. Diabetes classification; why is it important? 4. Suggested schemas for diabetes classification 5. Case presentation conclusions 6. Summary points and conclusions 3 Demonstrative cases Patient DL is a 56 yr old AA gentleman with a BMI of 24 referred for management of his “type 2 diabetes”. He is on basal bolus insulin with current HBA1c of 8.3. His greatest concern is on account of recent onset progressive neurologic symptoms and gaite unsteadiness Patient CY is a 21 yr old Caucasian lady with BMI of 28 and strong family history of diabetes referred for management of her “type 2 diabetes”. She is unsure if she even has diabetes as she indicates most of the SMBGs are under 160 and her current HBA1 is 6.4 on low dose metformin. Patient DR is a 54 yr old Asian lady with BMI of 36 and long standing “type 2 diabetes”. She has been referred because of poor diabetes control on multiple oral antidiabetics and persistent severe hypertriglyceridemia. Questions; Do all -

Relevance of Electrolytic Balance in Channelopathies

SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO-BICOCCA University of Milano-Bicocca School of Medicine and Surgery PhD Program in Translational and Molecular Medicine XXIX PhD course Relevance of electrolytic balance in channelopathies. Dr. Anna BINDA Matr. 708721 Tutor: Dr.ssa Ilaria RIVOLTA Coordinator: prof. Andrea BIONDI Academic year 2015-2016 2 Table of contents Chapter 1: introduction Channelopathies…………………………..…………………….….p. 7 Skeletal muscle channelopathies………………………….….…...p. 10 Neuromuscular junction channelopathies………………….……..p. 16 Neurological channelopathies……………………………….……p. 17 Cardiac channelopathies………………………………………..…p. 26 Channelopathies of non-excitable tissue………………………….p. 35 Scope of the thesis…………………………………………..…….p. 44 References………………………………………………….……..p. 45 Chapter 2: SCN4A mutation as modifying factor of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 2 phenotype…………………………..………..p. 51 Chapter 3: Functional characterization of a novel KCNJ2 mutation identified in an Autistic proband.…………………....p. 79 Chapter 4: A Novel Copy Number Variant of GSTM3 in Patients with Brugada Syndrome……………………………...………..p. 105 Chapter 5: Functional characterization of a mutation in KCNT1 gene related to non-familial Brugada Syndrome…………….p. 143 Chapter 6: summary, conclusions and future perspectives….p.175 3 4 Chapter 1: introduction 5 6 Channelopathies. The term “electrolyte” defines every substance that dissociates into ions in an aqueous solution and acquires the capacity to conduct electricity. Electrolytes have a central role in cellular physiology, in particular their correct balance between the intracellular compartment and the extracellular environment regulates physiological functions of both excitable and non-excitable cells, acting on cellular excitability, muscle contraction, neurotransmission and hormone release, signal transduction, ion and water homeostasis [1]. The most important electrolytes in the human organism are sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, calcium and chloride. -

The Histopathological Features of Muscular Dystrophies

SMGr up The Histopathological Features of Muscular Dystrophies Gulden Diniz* Pathologist, Microbiologist and Basic Oncologist, Neuromuscular Diseases’ Centre of Izmir Tepecik Education and Research Hospital, Turkey *Corresponding author: Gulden Diniz, Pathologist, Microbiologist and Basic Oncologist, Neuromuscular Diseases’ Centre of Izmir Tepecik Education and Research Hospital, Turkey. Email: [email protected] Published Date: September 23, 2016 ABSTRACT Muscular dystrophies are degenerative muscle diseases due to mutations in proteins ranging in function such as sarcolemmal structure, nuclear envelope structure, or post-translational suggesting that biological differences exist between individual muscles that predispose them to glycosylation. Each of them affects a specific group of skeletal muscles within the human body, specificClinical pathological manifestation etiologies. of different muscular dystrophies is now well known and documented. Dystrophinopathies are X-linked recessive diseases and the most common form of muscular dystrophies with a relatively poor outcome. Other recognized varieties of muscular dystrophies limb girdle muscular dystrophy is an umbrella name for a group of diseases which exhibits are classified into different groups according to their clinical or genetic similarities. For example, congenital muscular dystrophies is presentation prior to 1 year of age. proximal weakness of the shoulder and pelvic girdles. Similarly, the defining characteristic of Muscular Dystrophy | www.smgebooks.com 1 Copyright Diniz -

Triplet Repeat Diseases

1 Triplet Repeat Diseases Stephan J. Guyenet and Albert R. La Spada University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 1 A Novel Mechanism of Genetic Mutation Emerges 3 1.1 Repeat Sequences of All Types and Sizes 3 1.2 Trinucleotide Repeat Expansion as a Cause of Disease: Unique Features Explain Unusual Genetics 4 2 Repeat Diseases and Their Classification 5 2.1 Summary of Repeat Diseases 5 2.2 Differences in Repeat Sequence Composition and Location within Gene 6 2.3 Classification Based upon Mechanism of Pathogenesis and Nature of Mutation 6 3 Type 1: The CAG/Polyglutamine Repeat Diseases 9 3.1 Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy 9 3.2 Huntington’s Disease 12 3.3 Dentatorubral Pallidoluysian Atrophy 15 3.4 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 16 3.5 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 18 3.6 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3/Machado–Joseph Disease 19 3.7 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6 21 3.8 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 7 22 3.9 Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 17 25 3.10 Role of Aggregation in Polyglutamine Disease Pathogenesis 25 3.11 Protein Context 29 3.12 Transcriptional Dysregulation 30 3.13 Proteolytic Cleavage 30 4 Type 2: the Loss-of-function Repeat Diseases 33 4.1 Fragile X Syndrome 33 Encyclopedia of Molecular Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, 2nd Edition. Volume 15 Edited by Robert A. Meyers. Copyright 2005 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim ISBN: 3-527-30652-8 2 Triplet Repeat Diseases 4.2 Fragile XE Mental Retardation 34 4.3 Friedreich’s Ataxia 36 4.4 Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy Type 1 39 5 Type 3: the RNA Gain-of-function Repeat Diseases -

Technical Standards and Guidelines for Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Testing Thomas W

ACMG STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES Technical standards and guidelines for myotonic dystrophy type 1 testing Thomas W. Prior, PhD; on behalf of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Disclaimer: These standards and guidelines are designed primarily as an educational resource for clinical laboratory geneticists to help them provide quality clinical laboratory genetic services. Adherence to these standards and guidelines does not necessarily ensure a successful medical outcome. These standards and guidelines should not be considered inclusive of all proper procedures and tests or exclusive of other procedures and tests that are reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. In determining the propriety of any specific procedure or test, the clinical molecular geneticist should apply his or her own professional judgment to the specific clinical circumstances presented by the individual patient or specimen. It may be prudent, however, to document in the laboratory record the rationale for any significant deviation from these standards and guidelines. Abstract: Myotonic dystrophy type 1 is an autosomal dominant mul- Brief clinical description: Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) tisystem condition. Myotonic dystrophy type 1 is the result of an is an adult/congenital-onset multisystem disorder characterized unstable CTG expansion in the 3Ј-untranslated region of the myotonic by progressive muscle weakness, myotonia, intellectual impair- dystrophy protein kinase gene. The age of onset and the severity of the ment, cataracts, cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory insufficiency, phenotype are roughly correlated with the size of the CTG expansion. hypogonadism, and endocrine disturbances.1 The diagnosis can The combination of Southern transfer and polymerase chain reaction be problematic because of the wide range and severity of provides an accurate means of identifying patients affected by myotonic symptoms and often affected individuals will already have dystrophy type 1. -

Muscular Dystrophies: What the Radiologist Should Know

Muscular Dystrophies: What the radiologist should know J. Carmen Timberlake, MD; Kristina Siddall, MD; Christopher Bang, DO; Marat Bakman, MD; Gwy Suk Seo, MD; Johnny UV Monu, MD Department of Imaging Sciences University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY Presentation material is for education purposes only. All rights reserved. ©2006 URMC Radiology Page 1 of 39 Muscular Dystrophies: Introduction •! The muscular dystrophies are –! a group of inherited, progressive muscle disorders –! caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins required for normal muscle function. •! Biopsy reveals fiber degeneration –! this manifests clinically as weakness. Presentation material is for education purposes only. All rights reserved. ©2006 URMC Radiology Page 2 of 39 Muscular Dystrophies: Introduction •! Role of imaging in diagnosis and management –! Historically, diagnosis and evaluation of disease progression depend on clinical, pathologic, and biochemical parameters. –! Imaging has not been used for primary diagnosis or for routine follow-up evaluation. –! MRI, however, has a potential role in the work up, management, and study of muscular dystrophies Presentation material is for education purposes only. All rights reserved. ©2006 URMC Radiology Page 3 of 39 Muscular Dystrophies: Introduction Teaching points: 1.! Review of spectrum of muscular dystrophies. 2.! Review patterns of inheritance, pathophysiology of disease, clinical manifestations, and clinical management. 3.! Review radiologic findings in muscular dystrophies, with emphasis on -

Myotonic Dystrophy

Myotonic dystrophy Description Myotonic dystrophy is part of a group of inherited disorders called muscular dystrophies. It is the most common form of muscular dystrophy that begins in adulthood. Myotonic dystrophy is characterized by progressive muscle wasting and weakness. People with this disorder often have prolonged muscle contractions (myotonia) and are not able to relax certain muscles after use. For example, a person may have difficulty releasing their grip on a doorknob or handle. Also, affected people may have slurred speech or temporary locking of their jaw. Other signs and symptoms of myotonic dystrophy include clouding of the lens of the eye (cataracts) and abnormalities of the electrical signals that control the heartbeat (cardiac conduction defects). Some affected individuals develop a condition called diabetes mellitus, in which blood sugar levels can become dangerously high. The features of myotonic dystrophy often develop during a person's twenties or thirties, although they can occur at any age. The severity of the condition varies widely among affected people, even among members of the same family. There are two major types of myotonic dystrophy: type 1 and type 2. Their signs and symptoms overlap, although type 2 tends to be milder than type 1. The muscle weakness associated with type 1 particularly affects muscles farthest from the center of the body (distal muscles), such as those of the lower legs, hands, neck, and face. Muscle weakness in type 2 primarily involves muscles close to the center of the body ( proximal muscles), such as the those of the neck, shoulders, elbows, and hips. The two types of myotonic dystrophy are caused by mutations in different genes.