The Myotonic Dystrophies: Diagnosis and Management Chris Turner,1 David Hilton-Jones2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Letter Is for Families with Variant(S) in the Titin Gene, Also

This letter is for families with variant(s) in the Titin gene , also abbreviated as TTN . Changes in the Titin protein may cause muscle weakness as well as heart problems . You will need to discuss with your doctor if and how your Titin variant affects your health. What is Titin? Titin is a very large protein. It’s huge! In fact, Titin is the largest protein in the human body. The Titin protein is located in each of the individual muscle cells in our bodies. It is also found in the heart, which is a very specialized muscle. Muscles need Titin in order to work and move. You can learn more about Titin here: http://titinmyopathy.com . What is a Titin Myopathy? In medical terms, “Myo” refers to muscle and “-opathy” at the end of a word means that the word describes a medical disease or condition. So “myopathy” is a medical illness involving muscles. Myopathies result in muscle weakness and muscle fatigue. “Titin Myopathy” is a specific category of myopathy where the muscle problem is caused by a change in the Titin gene and subsequently the protein. What is a Titin-related Dystrophy? A Titin dystrophy is a muscle disorder where muscle cells break down. Dystrophies generally result in weakness that gets worse over time. A common heart problem caused by variants in the Titin gene is known as dilated cardiomyopathy. Sometimes other heart issues are also present in people with changes in their Titin gene. It is a good idea to have a checkup from a heart doctor if you have even a single variant in the Titin gene. -

X-Linked Myotubular Myopathy and Chylothorax

ARTICLE IN PRESS Neuromuscular Disorders xxx (2007) xxx–xxx www.elsevier.com/locate/nmd Case report X-linked myotubular myopathy and chylothorax Koenraad Smets * Department of Neonatology, Ghent University Hospital, De Pintelaan 185, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Received 10 August 2007; received in revised form 4 October 2007; accepted 24 October 2007 Abstract X-linked myotubular myopathy usually presents at birth with hypotonia and respiratory distress. Phenotypic presentation, however, can be extreme variable. We report on a newborn baby, who presented with the severe form of the disease. In the second week of life, he developed a clinically relevant chylothorax, needing drainage and treatment with octreotide acetate. Pleural effusions are frequently described in patients with congenital myotonic dystrophy. To our knowledge, the association of chylothorax and X-linked myotubular myopathy has not been described to date. As chylothorax could not be attributed to any evident condition in this child, perhaps it may be added to the clinical spectrum of X-linked myotubular myopathy. Ó 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: X-linked myotubular myopathy; Chylothorax 1. Introduction drainage (Fig. 1). Laboratory examination was compatible with chylothorax (5230 white blood cells/ll, 98% lympho- Congenital myopathies often present with hypotonia cytes; chylomicrons were present; triglycerides 746 mg/dl). and respiratory distress from birth, although their expres- There were no central venous catheters in place who could sion may be delayed. In most cases muscle biopsy is war- have caused thrombosis, impairing lymphatic flow, neither ranted for definitive diagnosis. In some instances could any other risk factor for chylothorax be identified. -

Consensus-Based Care Recommendations for Adults with Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1

Consensus-based Care Recommendations for Adults with Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 I Consensus-based Care Recommendations for Adults with Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Due to the multisystemic nature of this disease, the studies and rigorous evidence needed to drive the creation of an evidence-based guideline for the clinical care of adult myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) patients are not currently available for all affected body systems and symptoms. In order to improve and standardize care for this disorder now, more than 65 leading myotonic dystrophy (DM) clinicians in Western Europe, the UK, Canada and the US joined in a process started in Spring 2015 and concluded in Spring 2017 to create the Consensus-based Care Recommendations for Adults with Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. The project was organized and supported by the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation (MDF). A complete list of authors and an overview of the process is available in Addendum 1. A complete reading list for each of the study area sections is available in Addendum 2. An Update Policy has been adopted for this document and will direct a systematic review of literature and appropriate follow up every three years. Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation staff will provide logistical and staff support for the update process. A Quick Reference Guide extrapolated from the Consensus-based Care Recommendations is available here http://www.myotonic.org/clinical-resources For more information, visit myotonic.org. Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation 1 www.myotonic.org Table of Contents Life-threatening symptoms -

Skeletal Muscle Channelopathies: a Guide to Diagnosis and Management

Review Pract Neurol: first published as 10.1136/practneurol-2020-002576 on 9 February 2021. Downloaded from Skeletal muscle channelopathies: a guide to diagnosis and management Emma Matthews ,1,2 Sarah Holmes,3 Doreen Fialho2,3,4 1Atkinson- Morley ABSTRACT in the case of myotonia may be precipi- Neuromuscular Centre, St Skeletal muscle channelopathies are a group tated by sudden or initial movement, George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, of rare episodic genetic disorders comprising leading to falls and injury. Symptoms are UK the periodic paralyses and the non- dystrophic also exacerbated by prolonged rest, espe- 2 Department of Neuromuscular myotonias. They may cause significant morbidity, cially after preceding physical activity, and Diseases, UCL, Institute of limit vocational opportunities, be socially changes in environmental temperature.4 Neurology, London, UK 3Queen Square Centre for embarrassing, and sometimes are associated Leg muscle myotonia can cause particular Neuromuscular Diseases, with sudden cardiac death. The diagnosis is problems on public transport, with falls National Hospital for Neurology often hampered by symptoms that patients may caused by the vehicle stopping abruptly and Neurosurgery, London, UK 4Department of Clinical find difficult to describe, a normal examination or missing a destination through being Neurophysiology, King's College in the absence of symptoms, and the need unable to rise and exit quickly enough. Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, to interpret numerous tests that may be These difficulties can limit independence, London, UK normal or abnormal. However, the symptoms social activity, choice of employment Correspondence to respond very well to holistic management and (based on ability both to travel to the Dr Emma Matthews, Atkinson- pharmacological treatment, with great benefit to location and to perform certain tasks) and Morley Neuromuscular Centre, quality of life. -

Evidence-Based Guideline: Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management Of

Evidence-based Guideline: Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Issues Review Panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine Rabi Tawil, MD, FAAN1; John T. Kissel, MD, FAAN2; Chad Heatwole, MD, MS-CI3; Shree Pandya, PT, DPT, MS4; Gary Gronseth, MD, FAAN5; Michael Benatar, MBChB, DPhil, FAAN6 (1) MDA Neuromuscular Disease Clinic, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY (2) Department of Neurology, Wexner Medical Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH (3) Department of Neurology, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY (4) Department of Neurology, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY (5) Department of Neurology, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS (6) Department of Neurology, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL Correspondence to: American Academy of Neurology [email protected] 1 Approved by the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee on July 23, 2014; by the AAN Practice Committee on October 20, 2014; by the AANEM Board of Directors on [date]; and by the AANI Board of Directors on [date]. This guideline was endorsed by the FSH Society on December 18, 2014. 2 AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Rabi Tawil: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. John Kissel: acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. -

Myopathies Infosheet

The University of Chicago Genetic Services Laboratories 5841 S. Maryland Ave., Rm. G701, MC 0077, Chicago, Illinois 60637 Toll Free: (888) UC GENES (888) 824 3637 Local: (773) 834 0555 FAX: (773) 702 9130 [email protected] dnatesting.uchicago.edu CLIA #: 14D0917593 CAP #: 18827-49 Gene tic Testing for Congenital Myopathies/Muscular Dystrophies Congenital Myopathies Congenital myopathies are typically characterized by the presence of specific structural and histochemical features on muscle biopsy and clinical presentation can include congenital hypotonia, muscle weakness, delayed motor milestones, feeding difficulties, and facial muscle involvement (1). Serum creatine kinase may be normal or elevated. Heterogeneity in presenting symptoms can occur even amongst affected members of the same family. Congenital myopathies can be divided into three main clinicopathological defined categories: nemaline myopathy, core myopathy and centronuclear myopathy (2). Nemaline Myopathy Nemaline Myopathy is characterized by weakness, hypotonia and depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes. Weakness is typically proximal, diffuse or selective, with or without facial weakness and the diagnostic hallmark is the presence of distinct rod-like inclusions in the sarcoplasm of skeletal muscle fibers (3). Core Myopathy Core Myopathy is characterized by areas lacking histochemical oxidative and glycolytic enzymatic activity on histopathological exam (2). Symptoms include proximal muscle weakness with onset either congenitally or in early childhood. Bulbar and facial weakness may also be present. Patients with core myopathy are typically subclassified as either having central core disease or multiminicore disease. Centronuclear Myopathy Centronuclear Myopathy (CNM) is a rare muscle disease associated with non-progressive or slowly progressive muscle weakness that can develop from infancy to adulthood (4, 5). -

Clinical Approach to the Floppy Child

THE FLOPPY CHILD CLINICAL APPROACH TO THE FLOPPY CHILD The floppy infant syndrome is a well-recognised entity for paediatricians and neonatologists and refers to an infant with generalised hypotonia presenting at birth or in early life. An organised approach is essential when evaluating a floppy infant, as the causes are numerous. A detailed history combined with a full systemic and neurological examination are critical to allow for accurate and precise diagnosis. Diagnosis at an early stage is without a doubt in the child’s best interest. HISTORY The pre-, peri- and postnatal history is important. Enquire about the quality and quantity of fetal movements, breech presentation and the presence of either poly- or oligohydramnios. The incidence of breech presentation is higher in fetuses with neuromuscular disorders as turning requires adequate fetal mobility. Documentation of birth trauma, birth anoxia, delivery complications, low cord R van Toorn pH and Apgar scores are crucial as hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy remains MB ChB, (Stell) MRCP (Lond), FCP (SA) an important cause of neonatal hypotonia. Neonatal seizures and an encephalo- Specialist pathic state offer further proof that the hypotonia is of central origin. The onset of the hypotonia is also important as it may distinguish between congenital and Department of Paediatrics and Child Health aquired aetiologies. Enquire about consanguinity and identify other affected fam- Faculty of Health Sciences ily members in order to reach a definitive diagnosis, using a detailed family Stellenbosch University and pedigree to assist future genetic counselling. Tygerberg Children’s Hospital CLINICAL CLUES ON NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION Ronald van Toorn obtained his medical degree from the University of Stellenbosch, There are two approaches to the diagnostic problem. -

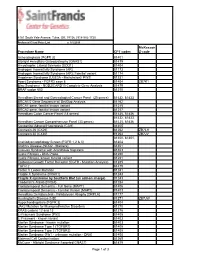

Procedure Name CPT Codes Mckesson Z-Code Achondroplasia

6161 South Yale Avenue, Tulsa, OK, 74136 | 918-502-1720 Preferred Client Price List v. 1/1/2019 McKesson Procedure Name CPT codes Z-code Achondroplasia {FGFR 3} 81401 Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy {GNAS1} 81479 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis {SOD1} 81404 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome {AR} 81173 Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome {AR}; Familial variant 81174 Angelman Syndrome {UBE3A - Methylation}/ PWS 81331 Apert Syndrome - FGFR2 exon 8 81404 ZB7K1 Blau Syndrome - NOD2/CARD15 Complete Gene Analysis 81479 BRAF codon 600 81210 Hereditary Breast and Gynecological Cancer Panel (25 genes) 81432, 81433 BRCA1/2 Gene Sequence w/ Del/Dup Analysis 81162 BRCA1 gene, familial known variant 81215 BRCA2 gene, familial known variant 81217 Hereditary Colon Cancer Panel (18 genes) 81435, 81436 81432, 81433, Hereditary Cancer Comprehensive Panel (33 genes) 81435, 81436 Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia {CAH} 81405 Connexin 26 {CX26} 81252 ZB7LH Connexin 30 {CX30} 81254 ZB7JV 81400, 81401, Craniodysmorphology Screen {FGFR 1,2 & 3} 81404 Crohn's Disease {NOD2 - Markers} 81401 Crouzon Syndrome with Acanthosis Nigricans 81403 Cystic Fibrosis - DNA Probe 81220 Cystic Fibrosis, known familial variant 81221 Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor {EGFR - Mutation Analysis} 81235 FGFR 2 81479 Factor V Leiden Mutation 81241 Fragile X Syndrome {FRAX1} 81243 Fragile X syndrome by Southern Blot (an add-on charge) 81243 Friederich's Ataxia {FRDA} 81284 Frontotemporal Dementia - Full Gene (MAPT) 81406 Frontotemporal Dementia - Familial Variant (MAPT) 81403 Hereditary Dentatorubral -

Congenital Muscular Dystrophy with Characteristic Radiological Findings Similar to Those with Fukuyama Congenital Muscular Dystrophy

Case Report Congenital muscular dystrophy with characteristic radiological findings similar to those with Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy Ajay Garg, Sheffali Gulati*, Vipul Gupta, Veena Kalra* Departments of Neuroradiology and *Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi, India. Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) is the quired social smile at 2 months, partial head control at 8 months, started sitting with support at 9 months and sitting without support most common congenital muscular dystrophy in Japan and at 18 months. He had no seizures. On examination, he had head lag there are isolated reports of non-Japanese patients with and hypotonia. Power was 3/5 in all limbs. Deep tendon jerks were FCMD. We report an Indian patient with congenital muscu- not elicitable. There was no muscle hypertrophy. The ophthalmic lar dystrophy and characteristic radiological findings similar examination, visual evoked potentials, motor nerve conduction stud- to those with FCMD. ies and EEG were normal. Electromyography showed a myopathic pattern. Serum creatine kinase was elevated at 2970 U/l (normal Key Words: Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy, con- 24-190 U/l). genital muscular dystrophy Cranial MRI revealed disorganized cerebellar folia with multiple cysts within vermis and cerebellar hemispheres (Figures 1a and 1b). There was marked pontine, and inferior vermian hypoplasia and fused midbrain colliculi (Figure 2a). The frontal lobes had shallow sulci Introduction and a bizarre pattern of the sulci parallel to each other without per- pendicular sulci (Figures 2a and 2b). There was ventriculomegaly and abnormal increased signal in periventricular white matter. The Congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) is a heterogeneous corpus callosum had a bizarre configuration, though was not hypo- group of disorders characterized by muscular hypotonia of plastic. -

Why Do We Get New Families with Myotonic Dystrophy?

5 to 20 mutation 5 This mutation event probably only occurred once in human evolution in the shared common ancestor of 13 all Myotonic Dystrophy families. 11 12 14 15 20 to 35 20 repeats Repeats in this 5 to 15 repeats range are not 21 Repeats in this range associated with any are not associated symptoms and are 22 with any symptoms present at quite and are present at high frequency high frequency in the in the general 23 general population. population. They are They are genetically genetically unstable 24 very stable when when transmit- transmitted chang- ted, but increase in ing only very rarely. length quite slowly. 25 There is essen- There is definite tially zero risk of new risk of new Myo- 27 Myotonic Dystrophy tonic Dystrophy families arising from families arising from individuals with such individuals with such 30 repeats. repeats, but it may take many hundreds 33 of generations. 40 to 50 repeats 35 Repeats in this range are not associated with any symptoms, but are present at only very 40 low frequencies in the general population. They are though genetically unstable when transmitted, increasing in length very rapidly 45 and leading to new Myotonic Dystrophy families within a few generations. 50 60 to 3000 repeats 80 Repeats in this range are associated directly with Myotonic Dystrophy symptoms. The repeat is genetically very unstable and expands 300 rapidly in sucessive generations giving rise to the increased severity and decreased age of onset 1000 observed in Myotonic Dystrophy families. Myotonic Dystrophy Support Group Helpline 0115 987 0080 Myotonic dystrophy affects a wide range of body systems and varies dramatically in the relative severity of the symptoms and the age at which the first symptoms appear. -

Swallowing Diff Iculties in Myotonic Dystrophy

Swallowing Diff iculties in Myotonic Dystrophy by Jodi Allen Specialist Speech & Language Therapist, The National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery, London Swallowing difficulties are an important aspect of Myotonic Dystrophy due to potentially serious complications. They should be identified early to help reduce risk of life-threatening complications. Management options often include swallowing strategies and sometimes alternative routes of feeding. These will be outlined as part of this booklet. Brief Summary • Myotonic Dystrophy can affect the muscles of your face, mouth and throat. • Weakness or stiffness (myotonia) in these muscles can cause problems with swallowing. • Swallowing problems can lead to weight loss and chest infections. • Problems can be identified early by looking out for signs and symptoms. These may include longer mealtimes, food sticking in the throat, needing to drink with meals and coughing and spluttering. Myotonic Dystrophy Support Group Helpline 0115 987 0080 • Swallowing problems should be assessed by a Speech and Language Therapist who can provide you with tailored advice and options. How do we normally eat and drink? The wind pipe (known as the trachea) and food pipe (known as the oesophagus) sit very close together in the throat, as shown below. The airway and food pipe sit close together in the throat When talking or engaging in an activity other than eating and drinking, the airway is open. This allows oxygen to pass into the lungs and expel waste gases out. At these times the entrance to the food pipe is closed. At regular intervals we initiate ‘a swallow.’ This allows saliva to move from the mouth into the food pipe. -

Beyond Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes; Why Correct Diabetes Classification Is Important Gabriel I. Uwaifo, MD Dept of Endocrinology

Beyond Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes; Why Correct Diabetes Classification is Important Gabriel I. Uwaifo, MD, FACP, FTOS, FACE. Dept of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Weight Management, Ochsner Medical Center Objectives To highlight various classification methods of diabetes To highlight the importance and consequences of appropriate diabetes classification To provide suggested processes for diabetes classification in primary care settings and indices for specialty referral Presentation outline 1. Case presentations 2. Diabetes classification; past present and future 3. Diabetes classification; why is it important? 4. Suggested schemas for diabetes classification 5. Case presentation conclusions 6. Summary points and conclusions 3 Demonstrative cases Patient DL is a 56 yr old AA gentleman with a BMI of 24 referred for management of his “type 2 diabetes”. He is on basal bolus insulin with current HBA1c of 8.3. His greatest concern is on account of recent onset progressive neurologic symptoms and gaite unsteadiness Patient CY is a 21 yr old Caucasian lady with BMI of 28 and strong family history of diabetes referred for management of her “type 2 diabetes”. She is unsure if she even has diabetes as she indicates most of the SMBGs are under 160 and her current HBA1 is 6.4 on low dose metformin. Patient DR is a 54 yr old Asian lady with BMI of 36 and long standing “type 2 diabetes”. She has been referred because of poor diabetes control on multiple oral antidiabetics and persistent severe hypertriglyceridemia. Questions; Do all