The Politics of Bad Options Why It Has Been Difficult to Resolve the Eurozone’S Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jahresbericht 2015

Jahresbericht 2015 Jahresbericht 2015 DIE STIMME DER SOZIALEN MARKTWIRTSCHAFT Jahresbericht 2015 des Wirtschaftsrates der CDU e.V. im April 2016 vorgelegt Die Europäische Idee mit Leben füllen – Reformen in Deutschland voranbringen! Exportstark, innovationsreich, qualitativ hochwertig – Deutschland steht mit stetigem positiven Wirtschaftswachstum und soliden Staatsfinanzen an der Spitze Europas. Doch Europa steht an einer Wegscheide: Noch immer haben die EU-Mitglieds- länder in der Vergangenheit Lösungen für zukunftsweisende Fragen gefunden – für die Bewältigung der Wirtschaftskrise 2009, bei der Finanzmarktregulierung und der EU-Schuldenkrise, bis hin zur Griechenlandkrise. Doch an der Flüchtlingskrise kann Europa zerbrechen. Immer häufiger werden fest vereinbarte und gemeinsam geglaubte Werte in Frage gestellt. Die Länder Ost- und Südosteuropas kündigen faktisch das Schengen-Abkommen auf, und Großbritannien steht vor einer Volks- abstimmung über den Verbleib in der EU. Die EU-Schuldenkrise ist noch keinesfalls gelöst, und die Geldpolitik der EZB wird immer mehr zum Risiko, weil sie den Reformdruck auf die Krisenländer reduziert. Notwendig ist stattdessen eine überzeugen- de Agenda für Wachstum, Wettbewerbsfähigkeit und Stabilität, den EU-Binnenmarkt im Bereich der Dienstleistungen und der Digitalen Wirtschaft zu vollenden, die Arbeitsmärkte weiter zu flexibilisieren sowie ein vollumfängliches Freihandels- abkommen mit den USA abzuschließen. Wir sollten alle Kräfte bündeln, um die Europäische Idee wieder mit Leben zu füllen, statt in die Nationalstaaterei abzurutschen. Die internationalen Aufgaben dürfen zugleich die notwendige wirtschaftspolitische Erneuerung in Deutschland nicht über- decken. Im Herbst 2015 ging die Legislaturperiode der Großen Koalition in ihre zweite Halbzeit: Beschäftigungsrekord, Haus- haltsüberschüsse und verbesserte Konjunkturprognosen geben Anlass zur Freude und haben die Lebenssituation der Men- schen in unserem Land kurzfristig verbessert. -

Stephanuspost Nr. 1

Der Stephanuskreis der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion informiert Dezember 2015 Wir geben verfolgten Christen eine Stimme Der Stephanuskreis setzt sich für Religionsfreiheit ein Menschen überall auf der Welt werden verfolgt, weil sie an das glauben, an was auch die Mehrheit der Deutschen glaubt. Sie werden verurteilt, weil sie eine Bibel besitzen, in die Kirche gehen oder beten. Nur vereinzelt dringen Schick- sale von verfolgten und ermordeten Christen ins Blickfeld unserer Gesellschaft. Dabei ist die Wahrheit, Verfolgung von Christen ist nicht die Ausnahme, sondern in manchen Teilen der Welt traurige Regel. Doch ihr Leid wird noch im- mer zu wenig wahrgenommen. Ebenso wie das der vielen anderen unterdrückten religiösen Minderheiten, zu denen in einigen Ländern auch Muslime gehören. 87 Abgeordnete der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion ha- ben sich in dieser Wahlperiode im Stephanuskreis zusam- mengeschlossen, um diesem Unrecht eine entschlossene- re Stimme zu geben. Wir haben es uns zur Aufgabe ge- Foto: Tobias Koch Tobias Foto: macht, weltweit für Religionsfreiheit und religiöse Toleranz einzutreten und insbesondere verfolgten Christen ein Fo- Prof. Dr. Heribert Hirte MdB Vorsitzender des Stephanuskreises rum auf politischer Ebene einzuräumen. Einen geschütz- ten Raum, der ihnen die Freiheit gibt, auf ihre Situation aufmerksam zu machen und uns die Möglichkeit, Informa- zunehmend erwartet wird, dass Menschen sich mit ihrer tionen zu bündeln und aufzuklären. Religiosität ins Private zurückziehen, scheint einigen nicht Der Einsatz für verfolgte Christen und die damit einher- bewusst, wie essenziell die Religionsfreiheit als Grund- gehenden Bemühungen für das Grund- und Menschen- und Menschenrecht für ein friedliches Miteinander ist. Der recht der Religionsfreiheit haben in der öffentlichen Wahr- Respekt vor anderen Religionen, aber auch vor Atheisten ist nehmung noch immer nicht den Stellenwert, den sie ver- da fest mit eingeschlossen. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/27

Plenarprotokoll 19/27 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografscher Bericht 27. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 20. April 2018 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 17: Elisabeth Motschmann (CDU/CSU) ....... 2495 B a) Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU, SPD, Thomas Hacker (FDP) ................. 2496 D FDP und BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN: Martin Rabanus (SPD) ................. Die Gewaltexzesse gegen die Rohingya 2497 D stoppen – Für die vollständige Anerken- Martin Erwin Renner (AfD) ............. 2498 D nung als gleichberechtigte Volksgruppe in Myanmar Martin Rabanus (SPD) ................. 2499 D Drucksache 19/1708 ................ 2483 B Doris Achelwilm (DIE LINKE) .......... 2500 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Zaklin Nastic, Margit Stumpp (BÜNDNIS 90/ Michel Brandt, Heike Hänsel, weiterer Ab- DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 2501 B geordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Staatenlosigkeit weltweit abschaffen – Michael Frieser (CDU/CSU) ............ 2502 B Für das Recht, Rechte zu haben Helge Lindh (SPD) .................... 2503 B Drucksache 19/1688 ................ 2483 B Frank Schwabe (SPD) .................. 2483 B Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Jürgen Braun (AfD) ................... 2484 C Antrag der Abgeordneten Christian Dürr, Michael Brand (Fulda) (CDU/CSU) ....... 2486 A Dr. Florian Toncar, Frank Schäffer, weite- Dr. Lukas Köhler (FDP) ................ 2488 A rer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der FDP: Trendwende zur Eigentümernation in Michel Brandt (DIE LINKE) ............ 2489 A Deutschland einleiten – Für einen Freibe- trag bei der Grunderwerbsteuer Margarete Bause (BÜNDNIS 90/ Drucksache 19/1696 ................... DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 2490 A 2504 B Katja Hessel (FDP) .................... 2504 C Sebastian Brehm (CDU/CSU) ........... 2491 A Antje Tillmann (CDU/CSU) ............. 2505 B Dr. Daniela De Ridder (SPD) ............ 2491 D Albrecht Glaser (AfD) ................. 2506 C Martin Patzelt (CDU/CSU) .............. 2492 D Bernhard Daldrup (SPD) ................ 2507 C Jörg Cezanne (DIE LINKE) ............. 2508 D Tagesordnungspunkt 18: Lisa Paus (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) . -

Einblicke #76 Für Köln, Für Sie

PROF. DR. HERIBERT HIRTE, MdB BERLINER EINBLICKE #76 FÜR KÖLN, FÜR SIE. Ihr Bundestagsabgeordneter für den Kölner Süden und Westen informiert Anfang Juli 2019 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, liebe Freunde! Das war es mit der letzten Sitzungswoche vor der parlamentarischen Sommerpause. Natürlich geht die Arbeit im Wahlkreis weiter, aber, Sie erlauben es mir, nun „muss“ ich bis September nicht mehr nach Berlin und „darf“ vielmehr in unserem Köln arbei- ten, herrlich! Das letzte halbe Jahr war aus politischer Sicht durchaus turbulent – was dadurch leider oft unter- geht: Die Große Koalition hat entgegen ihrem aus- baufähigen Ruf fleißig und gut für unser Land gear- beitet. Ich gebe Ihnen dafür Beispiele aus dieser Wo- che, in der wir wichtige Themen und Gesetze beschlossen, beraten und debattiert haben: Erste Be- ratung der Gruppenanträge über Organspenden, An- trag für Gerechtigkeit für die SED-Opfer, Aufarbei- tung von DDR-Zwangsadoptionen, zweite und dritte Zwar geht der Deutsche Bundestag nun in seine parlamentarische Sitzungs- Lesung zum Staatsangehörigkeitsrecht, Gesetz zur pause, das bedeutet aber nun einmal nicht Sommerpause. Deshalb stehen steuerlichen Förderung von Forschung und Ent- nun zahrliche Termine in den Wahlkreisen an, die Nacharbeit und die Vorbe- wicklung, Gesetz zur Modernisierung und Stärkung reitung für den Herbst knüpfen nahtlos an. der beruflichen Bildung, Gesetze zur Grundsteuer, fünftes Gesetz zur Änderung des Telekommunikati- de Gewaltpotential ist die größte Gefahr für das onsgesetzes, der Schiene höchste Priorität einräu- friedliche Zusammenleben in unserem Land. Wenn men, mit nationaler Tourismusstrategie den Stand- Sie erschreckende Beispiele aus dem Alltag eines Po- ort Deutschland weiter stärken - die Liste wäre hier litikers hören möchten, sehen Sie hier die entspre- noch nicht zu Ende, aber ich möchte Sie nicht weiter chende Rede von CDU-MdB Marian Wendt aus Sach- quälen. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 171. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 13.Mai 2016 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einstufung der Demokratischen Volksrepublik Algerien, des Königreichs Marokko und der Tunesischen Republik als sichere Herkunftsstaaten Drs. 18/8039 und 18/8311 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 572 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 58 Ja-Stimmen: 424 Nein-Stimmen: 145 Enthaltungen: 3 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 13.05.2016 Beginn: 10:05 Ende: 10:08 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Iris Eberl X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Seite: 3 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. -

Stephanuspost Nr. 7 | Dezember 2019

Der Stephanuskreis der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion informiert Dezember 2019 An jedem Ort der Welt: Christenhass, Muslimhass oder Antisemitismus geht uns alle an! Heißt Religion gleichzeitig Frieden? Die Antwort auf diese Frage ist komplexer als es zunächst erscheint. Es ist ein ver- klärtes Bild von Religion, diese als reine Friedensbotschaf- ten zu verstehen. Seit Jahrhunderten verursachen religiöse Koch Tobias Foto: Spannungen blutige Konflikte. Dabei haben sich Kirchen und Anhänger religiöser Strömungen aus einem Gemenge aus populistischer Ideologie, religiöser Extreme und häu- fig vor allem aufgrund ihrer weltlichen Machtansprüche bekriegt. Die geistigen Grundlagen für unser modernes Verständ- nis von Staat und Kirche konnten sich erst seit dem 19. Jahrhundert durchsetzen. Die Säkularisierung ist eine spe- zifisch europäische Entwicklung. Vorweg standen die Emanzipation des mündigen Bürgers und der Rechtsstaat. Durch die Garantie personenbezogener Rechte verpflichte- ten sich Staaten, den Schutz für die verschiedenen konfessi- Sie ist nicht weit weg, sondern wir spüren sie täglich“. onellen und religiösen Ausprägungen sicherzustellen. Die Selbst in Europa ist Juden-, Moslem- oder Christenhass staatlich garantierte Religionsfreiheit schützt den Einzel- nicht zu verleugnen. nen und befriedet in der Theorie die Gesellschaft. In Das Thema Christenverfolgung ist kein exklusives für Deutschland hat exemplarisch die Weimarer Reichsverfas- die Christenheit, wie Muslimhass oder Antisemitismus sung von 1919 endgültig den „christlichen Staat“ beseitigt. auch nicht nur Sache von Muslimen oder Juden ist. Es be- Dies brachte, auch durch die rechtliche Gleichstellung von trifft uns alle, an jedem Ort der Welt. Der Wettbewerb der Religion und nichtreligiöser Weltanschauung, volle indivi- Werte und Systeme hat sich globalisiert, der Einfluss Chi- duelle und für die Religionsgemeinschaften institutionelle nas, und damit der Einfluss autoritärer Werte, wird weiter- Freiheit. -

The Committees of the German Bundestag 2 3 Month in and Month Out, the German Bundestag Adopts New Laws Or Amends Existing Legislation

The Committees of the German Bundestag 2 3 Month in and month out, the German Bundestag adopts new laws or amends existing legislation. The Bundestag sets up permanent committees in every electoral term to assist it in accomplishing this task. In these committees, the Members concentrate on a specialised area of policy. They discuss the items referred to them by the ple- nary and draw up recommen- dations for decisions that serve as the basis for the ple- nary’s decision. The permanent committees of the German Bundestag – at the heart of Parliament’s work The Bundestag is largely free to decide how many commit- tees it establishes, a choice which depends on the priori- ties it wants to set in its par- liamentary work. There are 24 committees in the 19th electoral term. They essen- tially mirror the Federal Government’s distribution of ministerial portfolios, corre- sponding to the fields for which the ministries are The Committee on Labour and responsible. This facilitates Social Affairs and the Com- parliamentary scrutiny of the mittee on Internal Affairs and Federal Government’s work, Community have 46 members another of the Bundestag’s each, making them among the central functions. largest committees. Only the That said, in establishing com- Committee on Economic mittees, the Bundestag also Affairs and Energy has more sets political priorities of its members: 49. The Committee own. For example, the com- for the Scrutiny of Elections, mittees responsible for sport, Immunity and the Rules of tourism, or human rights and Procedure is the smallest humanitarian aid do not have committee, with 14 members. -

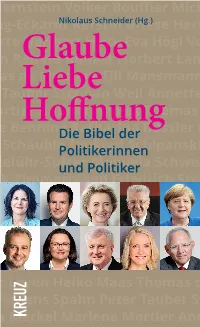

Glaube Liebe Hoffnung

Politikerbibel_Schu_Umschlag_print_Layout 1 15.08.2018 10:55 Seite 1 Ilse Aigner Annalena Baerbo ck Doroth e e Bär Melanie Bernstein Volker Bouffier Michael Brand Anna Nikolaus Schneider (Hg.) ) 1 . Christmann Maria FlachWeslchbe Baederuttunhg h atO die tBitbeol für mFerin eiicgenkese Leb eKn? aWetlchrer in Görg ing-Eckardt Kerstin Griese HermaMint Beniträg eGn vonrIlöse Ahigneer, An nMalena oBaenrbocik,k a H ( r Dorothee Bär, Sybille Benning, Melanie Bernstein, biblische Text ist mir am wichtigsten? Politikerinnen und Politiker e d Grütters Hubertus Heil Barbara Hendricks Christian Hi irte Heribert Hirte Eva Högl VolkVeolkerr B oKuffiear, Muichadel Breandr, A nnVa Choristlmkannm, ar e schreiben über ihren biblischen Lieblingstext und erklären, was n h Glaube Britta Dassler, Malu Dreyer, Maria Flachsbarth, c S Klein Julia Klöckner Pascal Kober Winfried Kretschma nn Renate Künast Norbert Lammert Werner Langen gerade dieses biblis che Wort für ihr Leben u nd po litisches Ha ndel n s Otto Fricke, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Kerstin Griese, u a bedeutet. Der Band zeigt eine in der Öffentlichkeit kaum bekannte l Hermann Gröhe, Markus Grübel, Monika Grütters, o Armin Laschet Ursula von der Leyen Heiko Maas Thomk as de Maizière Till Mansmann Elisabeth Mot - Seite der Po litike rinnen und Politike r. i N Liebe Hubertus Heil, Barbara Hendricks, Christian Hirte, schmann Nils Schmid Horst Seehofer Jens Spahn Peter Tauber Stephan Weil Annette WHeiridbertm Hirte, aEva nHögnl, Vol-keMr Kaudaer, uVolkzma r KMlein, ar - g Julia Klöckner, Pascal Kober, Winfried -

Plenarprotokoll 19/167

Plenarprotokoll 19/167 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 167. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 19. Juni 2020 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 26: Zusatzpunkt 25: a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD eingebrachten Ent- CDU/CSU und SPD eingebrachten Entwurfs wurfs eines Zweiten Gesetzes zur Umset- eines Gesetzes über begleitende Maßnah- zung steuerlicher Hilfsmaßnahmen zur men zur Umsetzung des Konjunktur- und Bewältigung der Corona-Krise (Zweites Krisenbewältigungspakets Corona-Steuerhilfegesetz) Drucksache 19/20057 . 20873 D Drucksache 19/20058 . 20873 B in Verbindung mit b) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregie- rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Zwei- ten Gesetzes über die Feststellung eines Zusatzpunkt 26: Nachtrags zum Bundeshaushaltsplan Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und für das Haushaltsjahr 2020 (Zweites SPD: Beschluss des Bundestages gemäß Ar- Nachtragshaushaltsgesetz 2020) tikel 115 Absatz 2 Satz 6 und 7 des Grund- Drucksache 19/20000 . 20873 B gesetzes Drucksache 19/20128 . 20874 A c) Antrag der Abgeordneten Kay Gottschalk, Marc Bernhard, Jürgen Braun, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD: in Verbindung mit Arbeitnehmer, Kleinunternehmer, Frei- berufler, Landwirte und Solo-Selbstän- Zusatzpunkt 27: dige aus der Corona-Steuerfalle befreien Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Dirk Spaniel, und gleichzeitig Bürokratie abbauen Wolfgang Wiehle, Leif-Erik Holm, weiterer Drucksache 19/20071 . 20873 C Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD: d) Antrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Deutscher Automobilindustrie zeitnah hel- Simone Barrientos, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, fen, Bahnrettung statt Konzernrettung, Be- weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion richte des Bundesrechnungshofs auch in DIE LINKE: Clubs und Festivals über der Krise beachten und umsetzen die Corona-Krise retten Drucksache 19/20072 . -

Stephanuspost Nr. 5

Der Stephanuskreis der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion informiert Weihnachten 2018 Ergreift Partei! Der Stephanuskreis mischt sich ein Willkürliche Inhaftierungen, Enteignungen, Beschränkun- wem können sich die bedrängten Christen weltweit Unter- gen von Studiums- und Arbeitsperspektiven, Schikanen, stützung erhoffen, wenn nicht von einem christlich ge- Folter und sogar Hinrichtungen – das alles sind Mittel, mit prägten Land wie Deutschland? „Das Kreuz, unter welches denen Regierungen oder Teile einer Gesellschaft Christen wir unsere Handlungen stellen, ist nicht nur Bekenntnis weltweit diskriminieren und bedrängen. Erst in diesem zur Nächstenliebe, die alles erträgt, alles glaubt, alles hofft, November wurden erneut mehrere Christen in Ägypten bei allem Stand hält“ (Kor 13,7). Es ist auch Ermächtigung, Par- einem Terroranschlag getötet. Für gro- tei zu ergreifen, Stellung zu beziehen ßes Aufsehen sorgte ihr Schicksal und für unsere Glaubensgeschwister nicht. Auch der Fall der wegen Blas- die Stimme zu erheben. Was kostet uns phemie angeklagten pakistanischen dieser Mut mit Blick auf die Leiden Christin Asia Bibi blieb jahrelang un- existenziell verfolgter Menschen? beachtet. Erst gegen Ende diesen Jah- Jeder von uns kann seinen Beitrag res machte ihr Schicksal Schlagzeilen, zur Religionsfreiheit leisten, mithel- wenn auch keine auf den Titelblättern. fen, dass wir das Menschenrecht Das Thema bedrängter und verfolgter durchsetzen können. Auch Atheisten Christen führt allenfalls ein Nischen- und Agnostiker sollten sich stärker für dasein. Mit dem schwindenden Ver- die Religionsfreiheit einsetzen. Denn ständnis für Religionen und Men- dort, wo Christen staatlich bedrängt schen, die ihren Glauben aktiv leben, und verfolgt werden, leiden auch ande- wächst eine gewisse Gleichgültigkeit re religiöse Minderheiten und auch in unserer Gesellschaft. Das kann zu Nichtgläubige. -

Wahlkreisbewerber/Innen Der CDU Nordrhein-Westfalen Zur Bundestagswahl 2013

Düsseldorf, 4. März 2013 Wahlkreisbewerber/innen der CDU Nordrhein-Westfalen zur Bundestagswahl 2013 WK# Wahlkreis Bewerber/in 87 Aachen I Rudolf Henke 88 Aachen II Helmut Brandt 89 Heinsberg Wilfried Oellers 90 Düren Thomas Rachel 91 Rhein-Erft-Kreis I Dr. Georg Kippels 92 Euskirchen – Rhein-Erft-Kreis II Detlef Seif 93 Köln I Karsten Möring 94 Köln II Prof. Dr. Heribert Hirte 95 Köln III Gisela Manderla 96 Bonn Dr. Claudia Lücking-Michel 97 Rhein-Sieg-Kreis I Elisabeth Winkelmeier-Becker 98 Rhein-Sieg-Kreis II Dr. Norbert Röttgen 99 Oberbergischer Kreis Klaus-Peter Flosbach 100 Rheinisch-Bergischer Kreis Wolfgang Bosbach 101 Leverkusen – Köln IV Helmut Nowak 102 Wuppertal I Peter Hintze 103 Solingen – Remscheid – Wuppertal II Jürgen Hardt 104 Mettmann I Michaela Noll 105 Mettmann II Peter Beyer 106 Düsseldorf I Thomas Jarzombek 107 Düsseldorf II Sylvia Pantel 108 Neuss I Hermann Gröhe 109 Mönchengladbach Dr. Günter Krings 110 Krefeld I – Neuss II Ansgar Heveling 111 Viersen Uwe Schummer 112 Kleve Ronald Pofalla 113 Wesel I Sabine Weiss 114 Krefeld II – Wesel II Kerstin Radomski 115 Duisburg I Thomas Mahlberg 116 Duisburg II Volker Mosblech 117 Oberhausen – Wesel III Marie-Luise Dött Seite 1/2 WK# Wahlkreis Bewerber/in 118 Mülheim – Essen I Astrid Timmermann-Fechter 119 Essen II Jutta Eckenbach 120 Essen III Matthias Hauer 121 Recklinghausen I Philipp Mißfelder 122 Recklinghausen II Rita Stockhofe 123 Gelsenkirchen Oliver Wittke 124 Steinfurt I – Borken I Jens Spahn 125 Bottrop – Recklinghausen III Sven Volmering 126 Borken II Johannes Röring 127 Coesfeld – Steinfurt II Karl Schiewerling 128 Steinfurt III Anja Karliczek 129 Münster Sybille Benning 130 Warendorf Reinhold Sendker 131 Gütersloh I Ralph Brinkhaus 132 Bielefeld – Gütersloh II Lena Strothmann 133 Herford – Minden-Lübbecke II Dr. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/177

Plenarprotokoll 19/177 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 177. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 18. September 2020 Inhalt: Präsident Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble . 22253 A Sabine Dittmar (SPD) . 22255 D Änderungen der Tagesordnung . 22253 D Dr. Andrew Ullmann (FDP) . 22256 C Ralph Brinkhaus (CDU/CSU) (zur Geschäftsordnung) . 22254 A Harald Weinberg (DIE LINKE) . 22257 B Maria Klein-Schmeink (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 22258 A Tagesordnungspunkt 20: Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 22258 D a) – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von den Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD ein- Dr. Edgar Franke (SPD) . 22259 D gebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes für ein Zukunftsprogramm Krankenhäu- Maria Klein-Schmeink (BÜNDNIS 90/ ser (Krankenhauszukunftsgesetz – DIE GRÜNEN) . 22260 C KHZG) Dr. Claudia Schmidtke (CDU/CSU) . 22261 B Drucksachen 19/22126, 19/22609 . 22254 A – Bericht des Haushaltsausschusses gemäß § 96 der Geschäftsordnung Drucksache 19/22614 . 22254 B b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Tagesordnungspunkt 5: Ausschusses für Gesundheit d) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Bruno – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Detlev Hollnagel, Albrecht Glaser, Franziska Spangenberg, Jörg Schneider, Dr. Robby Gminder, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Schlund, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der AfD: Souveränität bewah- Fraktion der AfD: Abschaffung des ren – Grenzüberschreitungen der Euro- DRG-Systems im Krankenhaus und päischen Zentralbank begegnen, Nega- Einführung des Prospektiv-Regiona- tivzinsen verbieten und erstatten len-Pauschalensystems – PRP-System Drucksache 19/22461 . 22262 B – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Detlev Spangenberg, Marc Bernhard, Stephan Dr. Bruno Hollnagel (AfD) . 22262 C Brandner, weiterer Abgeordneter und Dr. André Berghegger (CDU/CSU) . 22263 B der Fraktion der AfD: Krankenhäuser in der Fläche erhalten – Wirtschaft- Frank Schäffler (FDP) . 22264 C liche Basis sichern, Bundesländer an- gemessen beteiligen Doris Barnett (SPD) .