Study Guide for Elektra, Fall 2008 by Amy R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

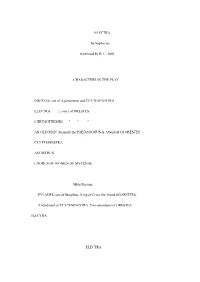

ELECTRA by Sophocles Translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS in THE

ELECTRA by Sophocles translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY ORESTES, son of Agamemnon and CLYTEMNESTRA ELECTRA } sister of ORESTES CHRYSOTHEMIS} " " " AN OLD MAN, formerly the PAEDAGOGUS or Attendant Of ORESTES CLYTEMNESTRA AEGISTHUS CHORUS OF WOMEN OF MYCENAE Mute Persons PYLADES, son of Strophius, King of Crisa, the friend Of ORESTES. A handmaid of CLYTEMNESTRA. Two attendants of ORESTES ELECTRA ELECTRA (SCENE:- At Mycenae, before the palace of the Pelopidae. It is morning and the new-risen sun is bright. The PAEDAGOGUS enters on the left of the spectators, accompanied by the two youths, ORESTES and PYLADES.) PAEDAGOGUS SON of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon!- now thou mayest behold with thine eyes all that thy soul hath desired so long. There is the ancient Argos of thy yearning,- that hallowed scene whence the gadfly drove the daughter of Inachus; and there, Orestes, is the Lycean Agora, named from the wolf-slaying god; there, on the left, Hera's famous temple; and in this place to which we have come, deem that thou seest Mycenae rich in gold, with the house of the Pelopidae there, so often stained with bloodshed; whence I carried thee of yore, from the slaying of thy father, as thy kinswoman, thy sister, charged me; and saved thee, and reared thee up to manhood, to be the avenger of thy murdered sire. Now, therefore, Orestes, and thou, best of friends, Pylades, our plans must be laid quickly; for lo, already the sun's bright ray is waking the songs of the birds into clearness, and the dark night of stars is spent. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays*

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays* The effects of recognition have to do with know- ledge and the means of acquiring it, with secrets, disguises, lapses of memory, clues, signs, and the like, and this no doubt explains the odd, almost asymmetrical positioning of anagnorisis in the domain of poetics… Structure and theme, poetics and interpretation, are curiously combined in this term… Terence Cave1 The fortuitous survival of three plays by each of the three tragic poets on the same story offers an unparalleled opportunity to consider some of the formal aspects of the genre, those which dictate the limits and possibilities of its dramatic enactment. Three salient elements constitute the irreducible minimum that characterizes the Orestes-Electra plot and is by necessity common to all three versions. These consist of nostos (return), anagnorisis (recognition) and mechanêma (the intrigue). This se- quence is known to us already from the Odyssey as the masterplot in the story of Odysseus himself and his return home, and it will come into play once again, nota- bly in Euripides’ version. Yet, at the same time, the Odyssey already contains the story of Orestes, who returns home to avenge his father, and it is this deed that pro- vides a contrapuntal line to the main story, which is that of the trials of Odysseus, his homecoming, his eventual vengeance on the suitors, and revelation of identity to friends and kin. The epic, however, gives only the bare facts of Orestes’ deed, which are recorded at the very outset in the proem (Od. -

Liz White Is an Actor Who Has Appeared in a Wide Variety of Roles on Stage and in Film and Television

Liz White is an actor who has appeared in a wide variety of roles on stage and in film and television. One of her most recent film roles was in Pride (2014) directed by Marcus Warchus. Among her other film roles, Liz has played Pamela in Vera Drake (2004) directed by Mike Leigh, and she starred as the eponymous woman in the 2012 film version of The Woman in Black, based on the novel by Susan Hill. For BBC Television, Liz played WPC/WDC Annie Cartwright in Life on Mars (2006/7), Caroline in the adaptation of The Crimson Petal and the White (2011), and Lizzie Mottershead in the series Our Zoo (2014). Other television roles have been Eileen in Teachers (2003), Jess Mercer in The Fixer (2008), and Lucille in The Paradise (2013). Liz’s stage credits have included three acclaimed performances at the National Theatre. She played Heavenly Critchfield in Laurie Sansom’s production of Spring Storm by Tennessee Williams, which transferred from the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, to the Cottesloe (2010), Anne Frankford in A Woman Killed With Kindness by Thomas Heywood, directed by Katie Mitchell in the Lyttelton (2010), and double roles in Marianne Elliot’s revival of Port by Simon Stephens in the Lyttelton (2013). In Autumn, 2014, Liz played the role of Chrysothemis in Ian Rickson’s production of Sophocles’ Electra at the Old Vic Theatre. The production used the version of the play written by Frank McGuinness and starred Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra. In this interview, recorded by Chrissy Combes at the Old Vic Theatre on Thursday 11 December 2014, Liz talked about the experience of playing Chrysothemis, Electra’s sister. -

Sophocles' Electra

Sophocles’ Electra Dramatic action and important elements in the play, scene-by-scene Setting: Mycenae/Argos Background: 15-20 years ago, Agamemnon (here named as grandson of Pelops) was killed by his wife and lover Aegisthus (also grandson of Pelops). As a boy, Orestes, was evacuated by his sister Electra and the ‘Old Slave’ to Phocis, to the kingdom of Strophius (Agamemnon’s guest-friend and father of Pylades). Electra stayed in Mycenae, preserving her father’s memory and harbouring extreme hatred for her mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. She has a sister, Chrysothemis, who says that she accepts the situation. Prologue: 1- 85 (pp. 169-75) - Dawn at the palace of Atreus. Orestes, Pylades and the Old Slave arrive. Topography of wealthy Argos/Mycenae, and the bloody house of the Atreids. - The story of Orestes’ evacuation. ‘It is time to act!’ v. 22 - Apollo’s oracle at Delphi: Agamemnon was killed by deception; use deception (doloisi – cunning at p. 171 is a bit weak) to kill the murderers. - Orestes’ idea to send the Old Slave to the palace. Orestes and Pylades will arrive later with the urn containing the ‘ashes’ of Orestes. «Yes, often in the past I have known clever men dead in fiction but not dead; and then when they return home the honour they receive is all the greater» v. 62-4, p. 173 Orestes like Odysseus: return to house and riches - Electra is heard wailing. Old slave: “No time to lose”. Prologue: 86-120 (pp. 175-7) - Enter Electra, who addresses the light of day. -

Elektra 2017

B Y J ANE G ANAHL The Many Faces of S E G A M I N A M E G Elektra D I R B ou may have seen her in the form of Jennifer YGarner’s sword-wielding assassin in the 2005 film Elektra , on stage as a bitter Civil War spin - ster in Eugene o’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra , in the words of Sylvia Plath’s controversial poem “Electra on Azalea Path,” in the famed portrait by Frederic Leighton, Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon , and indeed, in Richard Strauss’ opera Elektra* . K U , In the 2,000-plus years since her name was first S M U etched on paper, Electra—the myth, the character—has E S U inspired dozens, if not hundreds, of works of theater, lit - M L L erature, art, opera, and psychoanalysis. Around a cen - U H , tury ago, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung suggested there y R E L was an “Electra complex” suffered by many little girls L A G who were in love with their fathers in competition with T R A their mothers, thus tainting forever the innocent tag S N E “Daddy’s little girl.” R E F Even today, the vengeful, father-worshipping anti-heroine / S E of Sophocles’ tragedy continues to fascinate and perturb G A M I us—perhaps in part because her story of familial murder N A and mayhem makes Game of Thrones pale in comparison. M E G In the years following the Trojan War, Electra has waited D I R B for nearly a decade for the return of her brother orestes *When referring to the Sophocles play, the standard English spelling is “Electra.” “Elektra” is the German spelling. -

An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra

Rebellious Performances: An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra Bethany Nickerson Honors Thesis-English Department Advisor: Jeffrey DeShell, English Cathy Preston, English John Gibert, Classics March 22, 2012 Nickerson 1 Abstract This thesis seeks to create an understanding of the mythological characters of Clytemnestra and Electra as they were portrayed by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. By examining these plays in conjunction with the historical setting in which they were written and performed, this discussion shows how these two female characters play masculine roles in order to achieve their desires. These fictional women reveal how the real-life women of Classical Athens, were always caught in a double bind due to the patriarchal society in which they lived. This thesis examines the plays of these playwrights in their original Greek in order to examine how these women play masculine roles though their actions as well as the very words they use. This discussion ends with an examination of these female characters in relation to the male character Orestes which shows how these women are ultimately unsuccessful in their attempts to achieve their desires because they are, in the end, women. Nickerson 2 From the haunting song of the seductive sirens to the killing glare of Medusa and from the terrifying features of the chimera to the deadly riddles of the Sphinx, the feminine often appears in Greek mythology as perilous and evil. In the literature and myths of the Greeks from the earliest poems of the archaic period to the sophisticated dramas of Classical Athens, there emerges a pervasive fear of women. -

Compassion in Sophocles' Electra

Compassion in Sophocles' Electra Electra might seem an odd choice for a drama to illustrate the theme of compassion, but the theme is presented in this play in a relatively straightforward manner. Also, in Electra Sophocles develops the theme of compassion dramatically in ways that closely anticipate his development of compassion in his last two extant plays, Philoctetes and Oedipus at Colonus. The play presents the reunion of Electra with her brother Orestes during the execution of the plot developed by Orestes, his friend Pylades, and Orestes’ Paedagogus to execute Clytemnestra and Aegisthus for their murder of Orestes’ and Electra’s father, Agamemnon. Compassion functions in Electra as a strong motivating force between friends that prompts Electra to end her sister Chrysothemis’ “illusion” that Orestes is alive; it also prompts Orestes to end Electra’s sorrow and suffering over the apparent loss of her brother, Orestes himself. Electra and Orestes are therefore characterized in the play as being capable of compassion. Furthermore, Aegisthus’ and Clytemnestra’s contrasting lack of compassion serves to motivate Electra and Orestes: Agamemnon’s death is repeatedly characterized as pitiful, undeserved and unlamented; this motivates the retribution against his murderers in accordance with the ethic, “no pity for those who show no pity.” The play does not seem to me to problematize that ethic. In fact, I will argue that the application and denial of compassion in this play conforms to expectations of reciprocity that were operational in ancient Greek society and were explored in the classic Greek tragedy of Sophocles. . -

An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra Bethany Nickerson University of Colorado Boulder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2012 Rebellious Performances: An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra Bethany Nickerson University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Nickerson, Bethany, "Rebellious Performances: An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 257. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rebellious Performances: An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra Bethany Nickerson Honors Thesis-English Department Advisor: Jeffrey DeShell, English Cathy Preston, English John Gibert, Classics March 22, 2012 Nickerson 1 Abstract This thesis seeks to create an understanding of the mythological characters of Clytemnestra and Electra as they were portrayed by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. By examining these plays in conjunction with the historical setting in which they were written and performed, this discussion shows how these two female characters play masculine roles in order to achieve their desires. These fictional women reveal how the real-life women of Classical Athens, were always caught in a double bind due to the patriarchal society in which they lived. This thesis examines the plays of these playwrights in their original Greek in order to examine how these women play masculine roles though their actions as well as the very words they use. -

Clytemnestra, Electra, and the Failure of Mothering on the Attic

CLYTEMNESTRA, ELECTRA, AND THE FAILURE OF MOTHERING ON THE ATTIC STAGE by DEANA PAIGE ZEIGLER (Under the Direction of Nancy Felson) ABSTRACT I first extract a normative model for mother-daughter relationships from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter as well as a story pattern of the succession narrative from Hesiod’s Theogony and Homer’s Odyssey . Using both of these patterns or models, I investigate the troubled relationship between Clytemnestra and Electra. In Sophocles’ Electra and Euripides’ Electra the behavior of each character not only fails to conform to the normative model of a mother- daughter pair, it, in fact, exceeds all negative expectations for a functional, reciprocal mother- daughter relationship. Nevertheless, Clytemnestra and Electra are both aware of these societal norms. Both characters are disadvantaged because of the limits of female power, for Clytemnestra at an earlier phase of her life before she killed Agamemnon and usurped the throne. This fact contributes to the failure in mothering and the reproduction of mothering on the Attic stage. INDEX WORDS: Mothers, Daughters, Ancient Greece, Greek Tragedy, Sophocles, Euripides, Electra, Clytemnestra, Succession CLYTEMNESTRA, ELECTRA, AND THE FAILURE OF MOTHERING ON THE ATTIC STAGE by DEANA PAIGE ZEIGLER B.A., The College of Charleston, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Deana Paige Zeigler All Rights Reserved CLYTEMNESTRA, ELECTRA, AND THE FAILURE OF MOTHERING ON THE ATTIC STAGE by DEANA PAIGE ZEIGLER Major Professor: Nancy Felson Committee: Charles Platter Chris Cuomo Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2008 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

Clytemnestra's Daughters by Christopher Shorr

Clytemnestra's Daughters by Christopher Shorr Based on the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides Christopher Shorr 1010 N. New Street Bethlehem, PA 18018 [email protected] 484-695-3564 © 2009 Christopher Shorr The Plot This play at times follows traditional plots, but moves between Euripides’, Sophocles’ and Aeschylus’ versions of the story of the house of Atreus, and at other times takes new turns. Special Thanks Special thanks to Sycamore Rouge, Moravian College, the Southampton Playwriting Conference and Touchstone Theatre, for their assistance in the development of the script, and to Rebecca Kolacki and Alanah Cervantes for their research assistance. Structure Divided into three acts, the play should be performed in two halves, separated by an intermission: Act I (Iphigenia); Intermission; Act II (Chrysothemis) and Act III (Electra) Music The play begins and ends with a few lines of a song. Although written with the 1937 song “Someday My Prince Will Come” by Larry Morey and Frank Churchill in mind, it may be difficult to secure rights to this song for performance. If that is the case, another song could be used. Something wistful and nostalgic with fairytale themes would be ideal. There are plenty of songs in the public domain that could work. Perhaps the 1917 song “I'm Always Chasing Rainbows” by Joe McCarthy and Harry Carroll: At the end of the rainbow there's happiness, And to find it how often I've tried, But my life is a race, just a wild goose chase, And my dreams have all been denied. Why have I always been a failure? What can the reason be? I wonder if the world's to blame, I wonder if it could be me. -

Ancient Greeks Today: Modern Adaptations of the Orestes Myth Arthur L

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Theater Summer Fellows Student Research 7-22-2016 Ancient Greeks Today: Modern Adaptations of the Orestes Myth Arthur L. Robinson Ursinus College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/theater_sum Part of the Playwriting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Robinson, Arthur L., "Ancient Greeks Today: Modern Adaptations of the Orestes Myth" (2016). Theater Summer Fellows. 2. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/theater_sum/2 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theater Summer Fellows by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Ursinus College Ancient Greeks Today Modern Adaptations of the Orestes Myth Arthur Robinson Professor Scudera 2 Introduction Scholar Verna A. Foster describes the act of revising or adapting as making something old fit “for a new cultural environment, or a new audience” (Foster 2). Take into consideration Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet; the original play borrows elements from the ancient tale known as Pyramus and Thisbe, and has been adapted itself into everything from musicals such as High School Musical and West Side Story, to a zombie film, Warm Bodies. Writers and artists revisit and rework this play into new forms in order to speak to their own audiences. With this in mind, my research focuses on adaptations of the Orestes myth, a Greek tragedy often retold.