The Rhetorical Function of Tecmessa, Chrysothemis, and Ismene in Tragedies of Sophocles and Selected Adaptations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukrainian Folk Singing in NYC

Fall–Winter 2010 Volume 36: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore Ukrainian Folk Singing in NYC Hindu Home Altars Mexican Immigrant Creative Writers National Heritage Award Winner Remembering Bess Lomax Hawes From the Director Since the found- a student-only conference. There are prec- Mano,” readers will enjoy fresh prose pieces ing of the New York edents for this format, also. In commenting and poetry in English and Spanish from a Folklore Society, the on the 1950 meeting, then-president Moritz recently published anthology, produced by organization has pro- Jagendorf wrote, “Another ‘new’ at the Mexican cultural nonprofit Mano a Mano, vided two consistent Rochester meeting was the suggestion to the New York Writers Coalition, and a group benefits of member- have an annual contest among students of of New York’s newest Spanish-language ship: receipt of a New York State colleges and universities for writers. Musician, discophile, and Irish- published journal— the best paper on New York State folklore. American music researcher Ted McGraw since 2000, Voices— The winner will receive fifty dollars, and his presents a preliminary report and asks Voices and at least one annual meeting. or her paper will be read before the mem- readers for assistance in documenting the In the early years, the annual meeting bers.” (It is unclear whether this suggestion fascinating history of twentieth-century took place jointly with the annual gathering was implemented!) button accordions made by Italian craftsmen of the New York Historical Association, The 2010 meeting was held at New York and sold to the Irish market in New York. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Alumni Revue! This Issue Was Created Since It Was Decided to Publish a New Edition Every Other Year Beginning with SP 2017

AAlluummnnii RReevvuuee Ph.D. Program in Theatre The Graduate Center City University of New York Volume XIII (Updated) SP 2016 Welcome to the updated version of the thirteenth edition of our Alumni Revue! This issue was created since it was decided to publish a new edition every other year beginning with SP 2017. It once again expands our numbers and updates existing entries. Thanks to all of you who returned the forms that provided us with this information; please continue to urge your fellow alums to do the same so that the following editions will be even larger and more complete. For copies of the form, Alumni Information Questionnaire, please contact the editor of this revue, Lynette Gibson, Assistant Program Officer/Academic Program Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Theatre, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. You may also email her at [email protected]. Thank you again for staying in touch with us. We’re always delighted to hear from you! Jean Graham-Jones Executive Officer Hello Everyone: his is the updated version of the thirteenth edition of Alumni Revue. As always, I would like to thank our alumni for taking the time to send me T their updated information. I am, as always, very grateful to the Administrative Assistants, who are responsible for ensuring the entries are correctly edited. The Cover Page was done once again by James Armstrong, maybe he should be named honorary “cover-in-chief”. The photograph shows the exterior of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, England and was taken in August 2012. -

Tragic Hero Analysis on Apollo in Rick Riordan's The

TRAGIC HERO ANALYSIS ON APOLLO IN RICK RIORDAN’S THE TRIALS OF APOLLO: THE HIDDEN ORACLE THESIS BY: KASYFUL GHOMAM REG. NUMBER: A73217114 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES UIN SUNAN AMPEL SURABAYA 2021 TRAGIC HERO ANALYSIS ON APOLLO IN RICK RIORDAN’S THE TRIALS OF APOLLO: THE HIDDEN ORACLE By: Kasyful Ghomam Reg. Number: A73217114 Approved to be examined by the Board of Examiners, English Department, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya Surabaya, July 18ᵗʰ, 2021 Thesis Advisor Sufi Ikrima Sa’adah M. Hum NUP. 201603318 Acknowledged by: Head of English Department Dr. Wahju Kusumajanti, M. Hum NIP. 197002051999032002 EXAMINER SHEET ii The Board of Examiners are: Examiner 1 Examiner2 Sufi Ikrima Sa’adah M. Hum Dr. Wahju Kusumajanti, M.Hum NUP. 201603318 NIP. 197002051999032002 Examiner 3 Examiner 4 Dr. Abu Fanani, S.s., M.Pd Ramadhina Ulfa Nuristama, M.A. NIP. 196906152007011051 NIP. 199203062020122019 Acknowledged by: The Dean of Faculty of Arts and Humanities UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya Name NIP iii iv v ABSTRACT Ghomam, K (2021). Tragic Hero Analysis On Apollo In Rick Riordan’s The Trials Of Apollo: The Hidden Oracle. English literature, UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya. Advisor: Dr. Sufi Ikrima Sa’adah, M.Hum. Keywords: tragic hero, Apollo, myth, catharsis This study aims to analyze the tragic hero shown by Apollo in Rick Riordan’s The Trials of Apollo: The Hidden Oracle. This study focuses on two research questions: How are the characteristics of a tragic hero shown by Apollo, and how did Apollo escape from a tragic hero in The Trails of Apollo: The Hidden Oracle. -

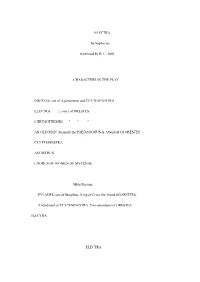

ELECTRA by Sophocles Translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS in THE

ELECTRA by Sophocles translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY ORESTES, son of Agamemnon and CLYTEMNESTRA ELECTRA } sister of ORESTES CHRYSOTHEMIS} " " " AN OLD MAN, formerly the PAEDAGOGUS or Attendant Of ORESTES CLYTEMNESTRA AEGISTHUS CHORUS OF WOMEN OF MYCENAE Mute Persons PYLADES, son of Strophius, King of Crisa, the friend Of ORESTES. A handmaid of CLYTEMNESTRA. Two attendants of ORESTES ELECTRA ELECTRA (SCENE:- At Mycenae, before the palace of the Pelopidae. It is morning and the new-risen sun is bright. The PAEDAGOGUS enters on the left of the spectators, accompanied by the two youths, ORESTES and PYLADES.) PAEDAGOGUS SON of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon!- now thou mayest behold with thine eyes all that thy soul hath desired so long. There is the ancient Argos of thy yearning,- that hallowed scene whence the gadfly drove the daughter of Inachus; and there, Orestes, is the Lycean Agora, named from the wolf-slaying god; there, on the left, Hera's famous temple; and in this place to which we have come, deem that thou seest Mycenae rich in gold, with the house of the Pelopidae there, so often stained with bloodshed; whence I carried thee of yore, from the slaying of thy father, as thy kinswoman, thy sister, charged me; and saved thee, and reared thee up to manhood, to be the avenger of thy murdered sire. Now, therefore, Orestes, and thou, best of friends, Pylades, our plans must be laid quickly; for lo, already the sun's bright ray is waking the songs of the birds into clearness, and the dark night of stars is spent. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

UWL LCM Welcome to Thebes Programme 2021

BA (Hons) Acting and BA (Hons) Actor Musicianship present WELCOME TO THEBES A play by Moira Buffini London College of Music @LCMLive Streaming Online LCMLive 17 – 20 June 2021 London College of Music Director’s Note Cast and Characters After ten years of brutal civil war, When Sophocles was writing in Athens Cast Character Eurydice and her government are in the fifth century BCE, Thebes was an preparing to lead Thebes into its enemy territory. Although almost on its Lorraine Adeyefa Eurydice (Cast 1) / Helia (Cast 2) new life as a democracy. Holding the doorstep – just one day’s trek across a Christian Bludell Xenophanes (Cast 1) / Prince Tydeus (Cast 2) new-found peace by their fingertips, mountain – it was mythic and distant. A Theodoros Charalambous Tiresias they face danger on all sides. At home, point of departure in our process was to war lords seeking to profit from chaos consider the people stranded in refugee Rose De Vera Pargeia stir up rebellion, while outside their camps in Greece today: to ask who Jenna Dyckhoff Megaera / Eunomia gates, neighbouring Sparta is looking they are, where they have come from to extend its empire. Their only hope and what is our responsibility to them. Molly Evans Antigone is to secure the help of democratic Forced out, homes destroyed, they have Sophia Ford Aglaea superpower Athens. risked their lives to flee circumstances we can barely imagine, in order simply Tiana Mai Jackson Euphrosyne and Harmonia Moira Buffini relocates Oedpius’ cursed to live. During the pandemic, the Kofi Jordan Prince Tydeus (Cast 1) / Xenophanes (Cast 2) family to the twenty-first century in situation of these already vulnerable a radical reimagining of Sophocles’ people continues to worsen. -

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays*

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays* The effects of recognition have to do with know- ledge and the means of acquiring it, with secrets, disguises, lapses of memory, clues, signs, and the like, and this no doubt explains the odd, almost asymmetrical positioning of anagnorisis in the domain of poetics… Structure and theme, poetics and interpretation, are curiously combined in this term… Terence Cave1 The fortuitous survival of three plays by each of the three tragic poets on the same story offers an unparalleled opportunity to consider some of the formal aspects of the genre, those which dictate the limits and possibilities of its dramatic enactment. Three salient elements constitute the irreducible minimum that characterizes the Orestes-Electra plot and is by necessity common to all three versions. These consist of nostos (return), anagnorisis (recognition) and mechanêma (the intrigue). This se- quence is known to us already from the Odyssey as the masterplot in the story of Odysseus himself and his return home, and it will come into play once again, nota- bly in Euripides’ version. Yet, at the same time, the Odyssey already contains the story of Orestes, who returns home to avenge his father, and it is this deed that pro- vides a contrapuntal line to the main story, which is that of the trials of Odysseus, his homecoming, his eventual vengeance on the suitors, and revelation of identity to friends and kin. The epic, however, gives only the bare facts of Orestes’ deed, which are recorded at the very outset in the proem (Od. -

Liz White Is an Actor Who Has Appeared in a Wide Variety of Roles on Stage and in Film and Television

Liz White is an actor who has appeared in a wide variety of roles on stage and in film and television. One of her most recent film roles was in Pride (2014) directed by Marcus Warchus. Among her other film roles, Liz has played Pamela in Vera Drake (2004) directed by Mike Leigh, and she starred as the eponymous woman in the 2012 film version of The Woman in Black, based on the novel by Susan Hill. For BBC Television, Liz played WPC/WDC Annie Cartwright in Life on Mars (2006/7), Caroline in the adaptation of The Crimson Petal and the White (2011), and Lizzie Mottershead in the series Our Zoo (2014). Other television roles have been Eileen in Teachers (2003), Jess Mercer in The Fixer (2008), and Lucille in The Paradise (2013). Liz’s stage credits have included three acclaimed performances at the National Theatre. She played Heavenly Critchfield in Laurie Sansom’s production of Spring Storm by Tennessee Williams, which transferred from the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, to the Cottesloe (2010), Anne Frankford in A Woman Killed With Kindness by Thomas Heywood, directed by Katie Mitchell in the Lyttelton (2010), and double roles in Marianne Elliot’s revival of Port by Simon Stephens in the Lyttelton (2013). In Autumn, 2014, Liz played the role of Chrysothemis in Ian Rickson’s production of Sophocles’ Electra at the Old Vic Theatre. The production used the version of the play written by Frank McGuinness and starred Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra. In this interview, recorded by Chrissy Combes at the Old Vic Theatre on Thursday 11 December 2014, Liz talked about the experience of playing Chrysothemis, Electra’s sister. -

Chapter 5 Vision of Tiresias: a Review of Kipling's Poetry

Chapter 5 Vision of Tiresias: A Review of Kipling’s Poetry While referring to the duality in Kipling’s creative art, Harold Orel writes: Rudyard Kipling’s history as a writer illustrates one of the most serious problems in modern criticism, the relationship between members of the Establishment (in both England and the United States) and writers who, for one reason or another, do not seem to satisfy the Establishment’s expectations of what they should be saying and writing (213, italics author’s). It is this area where Kipling refuses to endorse the stance of the Establishment and offers alternative viewpoints that attracts the attention of Kipling scholars in the postcolonial period. In his personal life, too, Kipling chose to stay miles away from the formality and grandeur of the officialdom of the Raj. His refusal of the ‘Knighthood’ offered to him in 1899 and 1903 by Lord Salisbury and Balfour consecutively, bears evidence to this statement (Carrington 393). The same accounts for his refusal to join the royal party thrown in the honour of the Prince of Wales (later King George V) in 1903 and 1911 on the occasion of his trip to India (393). All these instances only hint at Kipling’s notion of the Empire, which far from being monolithic, is replete with contradictions and subversive ironies. In this chapter I am going to focus on several of his poems bearing testimony to his gradual disillusionment with the Raj. A good number of poems such as “The overland Mail” (1886) or “The White Man’s Burden” (1899) reflect the myth of White superiority. -

Furbish'd Remnants

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Furbish’d Remnants”: Theatrical Adaptation and the Orient, 1660-1815 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Angelina Marie Del Balzo 2019 Ó Copyright by Angelina Marie Del Balzo 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Furbish’d Remnants”: Theatrical Adaptation and the Orient, 1660-1815 by Angelina Marie Del Balzo Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Felicity A. Nussbaum, Chair Furbish’d Remnants argues that eighteenth-century theatrical adaptations set in the Orient destabilize categories of difference, introducing Oriental characters as subjects of sympathy while at the same time defamiliarizing the people and space of London. Applying contemporary theories of emotion, I contend that in eighteenth-century theater, the actor and the character become distinct subjects for the affective transfer of sympathy, increasing the emotional potential of performance beyond the narrative onstage. Adaptation as a form heightens this alienation effect, by drawing attention to narrative’s properties as an artistic construction. A paradox at the heart of eighteenth-century theater is that while the term “adaptation” did not have a specific literary or theatrical definition until near the end of the period, in practice adaptations and translations proliferated on the English stage. Anticipating Linda Hutcheon’s postmodernist theory of adaptation, eighteenth-century playwrights and performers conceptualized adaptation as both process and product. Adaptation created a narrative mode that emphasized the process and labor of performance for audiences in order to create a higher level of engagement with ii audiences. -

Hermes As Guide and Leader of Souls by Brian Clark

CROSSING THE THRESHOLD: Hermes as Guide and Leader of Souls Brian Clark The Threshold to the Underworld The classical motif of the hero’s descent into the underworld or katabasis has been used in psychoanalytic writings (especially Jungian) as a metaphor for a descent into unconscious terrain, which is dark and unknown, contrary to the Olympian ideals of the ego. The underworld sphere is unlike anything the hero has known to date: the values, customs and laws of this domain are alien. The encounter with the underworld terrain is a rich metaphor for passages in a life when the psychological landscape shifts and becomes unfamiliar. These passages in one’s life are evoked out of a sense of loss, grief or an encounter with death. The space that separates the two spheres between what has been known, but now lost, and what is unknown but looming ahead is a liminal or suspended state. What the hero has previously known is now suspended; old forms of familiarity are not available. The hero, symbolic of the conscious knowing of self and mastery of the world that encompassed him, now faces a descent into an alien realm that is dark, foreign and dangerous. The threshold between these two worlds (between what is known, light and conscious and what is unknown, dark and unconscious) requires guidance and direction. Once the threshold has been crossed into the unknown, the hero cannot be in control of this world through his strength; his identity now is suspended and the fixed mental images that once bound him to the world are in flux.