Ancient Greeks Today: Modern Adaptations of the Orestes Myth Arthur L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Seneca's Trojan Women for Vce Students

NOTES ON SENECA’S TROJAN WOMEN FOR VCE STUDENTS Betty Gabriel-Jones Seneca’s Trojan Women, is, like most of his plays, modelled on a Greek original, Eurip- ides’ Women of Troy. However, he brings a distinctly Roman attitude to his plays, an attitude no doubt at least partly formed by a life led in and around the courts of the Julio-Claudian emperors. Seneca thrived under Tiberius, fell out of favour with Caligula, returned to Rome on Caligula’s death, was exiled by Claudius, then recalled, became influential at the court of Nero (indeed was probably the second most powerful man in Rome, after the emperor) and was eventually sentenced to death by Nero. This eventful and, one assumes, stressful life surely played a part in his somewhat pessimistic view of life. It is hard to see how this could not be the case. After all, his protégé, Nero, murdered his own stepbrother, his stepsister/wife and his mother Agrippina. His second wife, whom he supposedly loved, he kicked to death in a drunken rage. Witnessing such events, even if one were not involved, would not lead one to see life as a sunny, cheerful affair. And Seneca was not uninvolved. He was no innocent, and may even have condoned the killing of Agrippina; certainly he composed a speech for Nero in which he justified his action. In addition to all this, Seneca lived in a Rome where bloody and murderous games were the staple entertainment of the masses. By philosophy, Seneca was a stoic—that is to say, he advised a life designed around ra- tional behaviour, modesty, and discipline. -

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee's Iphigenia

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0: A Director’s Approach Caroline Donica Table of Contents Chapter One: Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 4 Introduction 4 The Life and Works of Charles Mee 4 Just War 8 Production History and Reception 11 Survey of Literature 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter Two: Play Analysis 16 Introduction 16 Synopsis 16 Given Circumstances 24 Previous Action 26 Dialogue and Imagery 27 Character Analysis 29 Idea and Theme 34 Conclusion 36 Chapter Three: The Design Process 37 Introduction 37 Production Style 37 Director’s Approach 38 Choice of Stage 38 Collaboration with Designers 40 Set Design 44 Costumes 46 Makeup and Hair 50 Properties 52 Lighting 53 Sound 55 Conclusion 56 Chapter Four: The Rehearsal Process 57 Introduction 57 Auditions and Casting 57 Rehearsals and Acting Strategies 60 Technical and Dress Rehearsals 64 Performances 65 Conclusion 67 Chapter Five: Reflection 68 Introduction 68 Design 68 Staging and Timing 72 Acting 73 Self-Analysis 77 Conclusion 80 Appendices 82 A – Photos Featuring the Set Design 83 B – Photos Featuring the Costume Design 86 C – Photos Featuring the Lighting Design 92 D – Photos Featuring the Concept Images 98 Works Consulted 102 Donica 4 Chapter One Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 Introduction Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0 is a significant work in recent theatre history. The play was widely recognized and repeatedly produced for its unique take on contemporary issues, popular culture, and current events set within a framework of ancient myths and historical literature. -

De Novis Libris Iudicia ∵

mnemosyne 70 (2017) 347-358 brill.com/mnem De Novis Libris Iudicia ∵ Carrara, L. L’indovino Poliido. Roma, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2014. xxiv, 497 pp. Pr. €48.00. ISBN 9788863726688. In this book Laura Carrara (C.) offers an edition with introduction and com- mentary (including two appendices, an extensive bibliography and indexes) of three fragmentary plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, which focus on the story of a mythical descendant of Melampus, the prophet and sorcerer Polyidus of Corinth, and his dealings with the son of Minos, Glaucus, whose life he saved. These plays are the Cressae, Manteis and Polyidus respectively. In the introduction C. gives an extensive survey of the sources on Polyidus in earlier periods and in literary genres other than tragedy. He plays a sec- ondary part in several stories (as in Pi. O. 13.74-84, where he is helping Bellerophon to control Pegasus) and only in the Cretan story about Glaucus he is the main character. C. observes that in archaic literature we find no traces of this story, but even so regards it as likely that the tragic poets did not invent it (perhaps finding it in an archaic Melampodia). Starting from Il. 13.636-672, where Polyidus predicts the death of his son Euchenor, C. first discusses the various archaic sources in detail and then goes on to various later kinds of prose and poetry, offering a full diachronic picture of the evidence on Polyidus. In the next chapter C. discusses a 5th century kylix, which is the only evidence in visual art of the Cretan story and more or less contemporary with the tragic plays. -

The Darkness of Man: a Study of Light and Dark Imagery in Seneca's

The Darkness of Man: A Study of Light and Dark Imagery in Seneca’s Thyestes and Agamemnon A Senior Thesis in Classics The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Emily Kohut May 2016 Kohut 1 Acknowledgments I would like to give my deepest and heartfelt thanks to Colorado College’s Classics department. Thank you Owen Cramer, Sanjaya Thakur, Marcia Dobson, and Richard Buxton for all of your help, edits, and advice throughout the course of my time here at CC and especially while working on this project. Thank you to my family and friends for supporting me through this whole process and to the many others who have been involved in my time here at CC. This has been an amazing experience and I could not have done it without all of you. Thank you very much. Kohut 2 The Darkness of Man: A Study of Light and Dark Imagery in Seneca’s Thyestes and Agamemnon Seneca’s Thyestes and Agamemnon are texts in which light rarely presents itself, instead it is dark that is present from start to finish. Throughout the course of these texts, I take note of the use and presence, or lack, of light. There appear to be two specific uses of light that serve specific purposes in Thyestes and Agamemnon: natural light (generally indicated with primarily die- or luc-1 based words), and artificial light (referenced by words related to/derived from flamma or ardeo2). Natural light is prominently used only when discussing its being consumed by darkness, while artificial light appears in passages saturated with destruction and chaos. -

AGAMEMNON PROLOGUE: Lines 1-39

AGAMEMNON PROLOGUE: Lines 1-39 GUARD: Watching from a WatchTower in Argos for the beacon of light announcing the fall of Troy! Laments of how long he has waited and watched with “elbow-bent, doglike,” without sleep. At prologues end, the beacon of light has brightened the sky. Guard has much joy, and hope that this will turn the house around. Imagery: Light/ Dark Lines 16-18: We know there is something amiss with how the house is being “administered.” The mix of anticipation and foreboding sets mood of the play. Something’s Coming. PARADOS: Prelude Lines 40- 103 What Character is the Chorus Playing? Lines 72-76 PRELUDE Continued WHAT’S GOING ON? - Trojan War has just ended after 10 years, but how did it began? MENELAUS- KING OF SPARTA AGAMEMNON- KING OF ARGOS/ BROTHER OF MENELAUS Vs. PARIS (ALEXANDER)- PRINCE OF TROY HELEN- Once Wife of Menelaus now Wife of Paris (Clytemnestra's Sister) “Promiscuous Girl, Stop Teasing Me” NESTRA: WAIT, SO MY HUSBAND LEFT TO FIGHT A WAR TO FORCE MY \ SISTER TO STAY MARRIED TO HIS BROTHER? CHORUS: YES, CLYTEMNESTRA. NESTRA: ALRIGHT, COOL. SO, I’M JUST GONNA TRY TO TAKE CARE OF THIS KINGDOM OF ARGOS THEN, I GUESS. CHORUS: BUT, WHY ARE YOU BURNING ALL THESE SACRIFICES FOR THE GODS AND ORDERING ALL THESE CELEBRATIONS? NESTRA: WELL… CHORUS: IMMA LET YOU FINISH BUT, I GOTTA TELL YOU ABOUT THIS OTHER MESS REAL QUICK.. PARADOS: Three-Part ODE Part One: STROPHE (East To West, or From Stage Right) ANTISTROPHE (West to East, or From Stage Left) EPODE (From Center, could be by one member of chorus or multiple) CALCHAS: I’m a Soothsayer and those two eagles eating that pregnant rabbit means VICTORY for the two brothers! ARTEMIS: Yes, but those eagles killed a pregnant rabbit. -

The Zodiac: Comparison of the Ancient Greek Mythology and the Popular Romanian Beliefs

THE ZODIAC: COMPARISON OF THE ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND THE POPULAR ROMANIAN BELIEFS DOINA IONESCU *, FLORA ROVITHIS ** , ELENI ROVITHIS-LIVANIOU *** Abstract : This paper intends to draw a comparison between the ancient Greek Mythology and the Romanian folk beliefs for the Zodiac. So, after giving general information for the Zodiac, each one of the 12 zodiac signs is described. Besides, information is given for a few astronomical subjects of special interest, together with Romanian people believe and the description of Greek myths concerning them. Thus, after a thorough examination it is realized that: a) The Greek mythology offers an explanation for the consecration of each Zodiac sign, and even if this seems hyperbolic in almost most of the cases it was a solution for things not easily understood at that time; b) All these passed to the Romanians and influenced them a lot firstly by the ancient Greeks who had built colonies in the present Romania coasts as well as via commerce, and later via the Romans, and c) The Romanian beliefs for the Zodiac is also connected to their deep Orthodox religious character, with some references also to their history. Finally, a general discussion is made and some agricultural and navigator suggestions connected to Pleiades and Hyades are referred, too. Keywords : Zodiac, Greek, mythology, tradition, religion. PROLOGUE One of their first thoughts, or questions asked, by the primitive people had possibly to do with sky and stars because, when during the night it was very dark, all these lights above had certainly arose their interest. So, many ancient civilizations observed the stars as well as their movements in the sky. -

Seagate Crystal Reports

GREEK VERSUS MODERN TRAGEDY IN ' EUGENE O’NEILL Maria do Perpétuo Socorro Rego e Reis Cosme Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Pós - Graduação em Inglês e Literatura Correspondente Greek Versus Modern Tragedy in Eugene O’Neill Maria do Pérpetuo Socorro Rego Reis Cosme Tese submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do Grau de Doutora em Letras opção Inglês e Literatura Correspondente. Florianópolis Esta tese foi julgada adequada e qjrovada em sua. forma. finaL pelo Programa de Pós- Gràduação em Inglês para obtenção do grau de Doutora em Letras Opção Inglês e Literatura-Correspondente Dra. Bárbara O Baptista Coordenadora Dra. Bamadete Pasold Orientadora Banca Examinadora Dra Bemadete PasoId(OrientaíWora) Dr. Donaldo Schüler ( examinador) Dr. Joséy^oberto O' Shea (examinador) Dra Patrícia Vaüghan (examinadora) Florianópolis, 30 de março de 1998 Dedico essa Tese com muita saudade ao meu querido pai: José Reis (In Memoriam)que durante a sua vida sempre sonhou com a minha obtenção do Grau de Doutora. Esta pesquisa também é dedicada com muito amor a : minha mãe Lauríta Reis pelo estímulo perene no decorrer do doutorado; meu esposo Antonio Cosme Neto pela força e coragem para que eu não desistisse do doutorado; meus filhos Márcio Elysio , Lysianne e principalmente o querido “editor “Erick Elysio por toda a compreensão e confiança na capacidade da mãe para terminar o “sofrido” doutorado; meus irmãos e parentes pela amizade e solidariedade ; todos os meus amigos e colegas de profissão que sempre confiaram na minha capacidade e pelo estimulo constante para eu continuar apesar de tudo. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Dra. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

Aeschylus' Libation Bearers

Libation Bearers By Aeschylus Translated by Jim Erdman Further Revised by Gregory Nagy At the tomb of Agamemnon. Orestes and Pylades enter. Orestes Hermes of the nether world, you who guard the powers [kratos] of the ancestors, prove yourself my savior [sōtēr] and ally, I entreat you, now that I have come to this land and returned from exile. On this mounded grave I cry out to my father to hearken, 5 to hear me... [There is a gap in the text.] [Look, I bring] a lock of hair to Inakhos1 in compensation for his care, and here, a second, in token of my grief [penthos]. For I was not present, father, to lament your death, nor did I stretch forth my hand to bear your corpse. 10 What is this I see? What is this throng of women that advances, marked by their sable cloaks? To what calamity should I set this down? Is it some new sorrow that befalls our house? Or am I right to suppose that for my father’s sake they bear 15 these libations to appease the powers below? It can only be for this cause: for indeed I think my own sister Electra is approaching, distinguished by her bitter grief [penthos]. Oh grant me, Zeus, to avenge my father’s death, and may you be my willing ally! 20 Pylades, let us stand apart, that I may know clearly what this band of suppliant women intends. They exit. Electra enters accompanied by women carrying libations. Chorus strophe 1 Sent forth from the palace I have come to convey libations to the sound of sharp blows of my hands. -

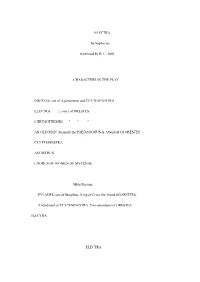

ELECTRA by Sophocles Translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS in THE

ELECTRA by Sophocles translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY ORESTES, son of Agamemnon and CLYTEMNESTRA ELECTRA } sister of ORESTES CHRYSOTHEMIS} " " " AN OLD MAN, formerly the PAEDAGOGUS or Attendant Of ORESTES CLYTEMNESTRA AEGISTHUS CHORUS OF WOMEN OF MYCENAE Mute Persons PYLADES, son of Strophius, King of Crisa, the friend Of ORESTES. A handmaid of CLYTEMNESTRA. Two attendants of ORESTES ELECTRA ELECTRA (SCENE:- At Mycenae, before the palace of the Pelopidae. It is morning and the new-risen sun is bright. The PAEDAGOGUS enters on the left of the spectators, accompanied by the two youths, ORESTES and PYLADES.) PAEDAGOGUS SON of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon!- now thou mayest behold with thine eyes all that thy soul hath desired so long. There is the ancient Argos of thy yearning,- that hallowed scene whence the gadfly drove the daughter of Inachus; and there, Orestes, is the Lycean Agora, named from the wolf-slaying god; there, on the left, Hera's famous temple; and in this place to which we have come, deem that thou seest Mycenae rich in gold, with the house of the Pelopidae there, so often stained with bloodshed; whence I carried thee of yore, from the slaying of thy father, as thy kinswoman, thy sister, charged me; and saved thee, and reared thee up to manhood, to be the avenger of thy murdered sire. Now, therefore, Orestes, and thou, best of friends, Pylades, our plans must be laid quickly; for lo, already the sun's bright ray is waking the songs of the birds into clearness, and the dark night of stars is spent. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

Aristotle and Sophocles' Electra

ARISTOTLE AND SOPHOCLES' ELECTRA ]. C. Kamerbeek viro de Soplwcle optinu merito 1. The key element of Aristotle's Poetics is the idea that each product of 1roi710-Ls is the imitation1 of an action. This action is defined as an ordered arrangement (<TVv0€0-LS or o-vo,ao-ts) of actions/events. The requirements to be met by the course of action, in this sense, provide the primary criteria for determining the quality of the individual pieces. A good <TUO-TaO"LS (alias: µ.v0os, for lack of a better term usually translated as 'plot') is a whole, consisting of a beginning, a middle and an end. The internal structure of the action is described with the aid of the central concepts €lKos and avayKa'iov: the events which, together, constitute the plot have to show close coherence in the sense that each subsequent event necessarily, or at least with a large degree of pro bability, follows from the preceding events. The ideal action is an action in which coincidence does not play a major part: everything is as it is because, in the light of preceding events, 2 it could not or could hardly have been otherwise. Judged by these fundamental criteria, Sophocles' Electra is far from satisfactory. The action in the restricted sense is summarized by Orestes (verse 38 ff.) as follows: Orestes, Pylades and the Pedagogue have come to Argos to take revenge on Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus for the murder of Agamemnon - an act which Apollo advised them to undertake 'by stratagem'. For this purpose, th<;_ Pedagogue will enter the palace to reconnoitre the situation and to bring the news of Orestes' death.