WORKING PAPERS Number 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Two-Popes-Ampas-Script.Pdf

THE TWO POPES Written by Anthony McCarten Pre-Title: Over a black screen we hear the robotic voice of a modern telephone system. VOICE: Welcome to Skytours. For flight information please press “1”. If you’re calling about an existing booking please press “2”. If you’re calling about a new booking please press “3” ... The beep of someone (Bergoglio) pressing a button. VOICE: (CONT’D) Did you know that you can book any flight on the Skytour website and that our discount prices are internet only ... BERGOGLIO: (V.O.) Oh good evening I ... oh. He’s mistaken this last for a human voice but ... VOICE: (V.O.) ... if you still wish to speak to an operator please press one ... Another beep. VOICE : (V.O.) Good morning welcome to the Skytours sales desk ... BERGOGLIO: (V.O.) Ah. Yes. I’m looking for a flight from Rome to Lampedusa. Yes I know I could book it on the internet. I’ve only just moved here. VOICE: Name? BERGOGLIO: Bergoglio. Jorge Bergoglio. VOICE: Like the Pope. 1 BERGOGLIO: Well ... yes ... in fact. VOICE: Postcode? BERGOGLIO: Vatican city. There’s a long pause. VOICE: Very funny. The line goes dead. Title: The Two Popes. (All the scenes that take place in Argentina are acted in Spanish) EXT. VILLA 21 (2005) - DAY A smartly-dressed boy is walking along the narrow streets of Villa 21 - a poor area that is exploding with music, street vendors, traffic. He struts past the astonishing murals that decorate the walls of the area. The boy is heading for an outdoor mass, celebrated by Archbishop Bergoglio. -

Law and Gospel Article

RENDER UNTO RAWLS: LAW, GOSPEL, AND THE EVANGELICAL FALLACY Wayne R. Barnes∗ I. INTRODUCTION Many explicitly Christian voices inject themselves frequently and regularly into the current public policy and political discourse. Though not all, many of these Christian arguments proceed in something like the following manner. X is condemned (or required) by God, as revealed in the Bible. Therefore, the explicitly-required “Christian position” on X is for the law to prohibit or limit the activity (or require it), in accordance with the advocate’s interpretation of biblical ethical standards. To be clear, I mean to discuss only those scenarios where a Christian publicly identifies a position as being mandated by Christian morality or values --- i.e., where the public is given a message that some law or public policy is needed in order to comply with the Christian scriptures or God’s will. That is, in short, this article is about explicit political communications to the public in overt religious language of what Christianity supposedly requires for law and policy. As will be seen, these voices come quite famously from the Christian Religious Right, but they come from the Religious Left as well. Political philosophers (most famously John Rawls) have posited that pluralism and principles of liberal democracy strongly counsel against resort to such religious views in support of or against any law or public policy.1 That is, in opposition to this overt religious advocacy in the political realm (though, it should be noted, not necessarily taking a substantive position on the issues, per se) is the position of Rawlsian political liberalism, which states generally that, all things being equal, such inaccessible religious arguments should not be made, but rather arguments should only be made by resort to “public reason” which all find to be accessible.2 Christian political voices counter that this results in an intolerable stifling of their voice, of requiring that they “bracket” ∗ Professor, Texas Wesleyan University School of Law. -

Box1 Folder 45 2.Pdf

e~'~/ .#'~; /%4 ~~ ~/-cu- 0 ~/tJD /~/~/~ :l,tJ-O ~~ bO:cJV " " . INTERNA TIONA L Although more Japanese women a.re working out.ide the home than ever belore, a recent lurvey trom that country lndicateB that they a re not likely to get very high on the eorpotate la.dder. The survey, carried out by a women-, magazlne, polled 500 Japanese corpora.tions on the qualltles they look tor when seekl.l'1! a temale staff member. I Accordlng to lhe KyGdo News Service.! 95'0 of the eompanlel said they look fop female workers who are cheerful and obedLent; 9Z% sou.,ht cooperative women; and 85% wanted temale employees wllllng to take respoDs!bllity. Moat firms indtcated that they seek women worker, willLng to perform tasks such as copying and making tea. CFS National Office 3540 14th Street Detroit, Michigan 48208 (31 3) 833-3987 Christians For Socialism in the u.S. Formerl y known as American Christians Toward Socialism (A CTS), CFS in the US " part of the international movement of Christians for Socialism. INTERN..A TIONA L December 10 i. Human Rightl Day aroUnd the world. But Ln Talwan, the arrests in recent yeaI'I of feminists, IdDIibt clvll rlghts advocate., lntellec.uals, and re11gious leaders only symbolize the lack of human rlghts. I Two years ago on Dec. 10 In Taiwan, a human rights day rally exploded 1nto violence ~nd more than ZOO people were arrested. E1ght of them, including two lemlnl.t leaders. were tried by milltary tribunal for "secUtlon, it convicted and received sentences of from 1Z years to Ufe. -

Barnabas Aid Magazine March/April 2021

barnabasaid.org MARCH/ barnabasaid APRIL 2021 BARNABAS AID - RELIEF AGENCY FOR THE PERSECUTED CHURCH - BRINGING HOPE TO SUFFERING CHRISTIANS NORTH KOREA INDIA ARMENIA Christian Survivors of the Secretive Old and New Forms of Barnabas Petition for Recognition State’s ”Re-Education” Camps Persecution on the Rise of Armenian Genocide The Barnabas Aid Distinctive What helps make Barnabas Aid distinctive from other Christian organizations that deal with persecution? We work by: communities, so they can maintain their presence and witness, rather than setting ● directing our aid only to Christians, up our own structures or sending out How to Find Us although its benefits may not be exclusive missionaries to them (“As we have opportunity, let us You may contact do good to all people, especially to those ● tackle persecution at its root by making Barnabas Aid at the who belong to the family of believers” known the aspects of other religions and following addresses: Galatians 6:10, emphasis added) ideologies that result in injustice and oppression of Christians and others ● channeling money from Christians through Christians to Christians (we do ● inform and enable Christians in the West International Headquarters not send people; we only send money) to respond to the growing challenge The Old Rectory, River Street, of other religions and ideologies to the Pewsey, Wiltshire SN9 5DB, UK ● channeling money through existing Church, society and mission in their own Telephone 01672 564938 structures in the countries where funds countries are sent (e.g. -

Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2010 Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For Leslie C. Griffin University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Politics Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Griffin, Leslie C., "Review Essay: Religion and Politics 2008-2009: Sometimes You Get What You Pray For" (2010). Scholarly Works. 803. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/803 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY RELIGION AND POLITICS 2008-2009 THUMPIN' IT: THE USE AND ABUSE OF THE BIBLE IN TODAY'S PRESIDENTIAL POLITICS. By Jacques Berlinerblau. Westminster John Knox Press 2008. Pp. x + 190. $11.84. ISBN: 0-664-23173-X. THE SECULAR CONSCIENCE: WHY BELIEF BELONGS IN PUBLIC LIFE. By Austin Dacey. Prometheus Book 2008. Pp. 269. $17.80. ISBN: 1-591- 02604-0. SOULED OUT: RECLAIMING FAITH AND POLITICS AFTER THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT. By E.J Dionne, Jr.. Princeton University Press 2008. Pp. 251. $14.95. ISBN: 0-691-13458-8. THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS LIBERTY By Anthony Gill. Cambridge University Press 2007. Pp. 263. Paper. $18.81. ISBN: 0-521- 61273-X. BLEACHED FAITH. THE TRAGIC COST WHEN RELIGION IS FORCED INTO THE PUBLIC SQUARE. By Steven Goldberg. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory 2020-2021

ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020-2021 Mission Basilica San Buenaventura, Ventura See inside front cover 01-FRONT_COVER.indd 1 9/16/2020 3:47:17 PM Los Angeles Archdiocesan Catholic Directory Archdiocese of Los Angeles 3424 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90010-2241 2020-21 Order your copies of the new 2020-2021 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory. The print edition of the award-winning Directory celebrates Mission San Buenaventura named by Pope Francis as the first basilica in the Archdiocese. This spiral-bound, 272-page Directory includes Sept. 1, 2020 assignments – along with photos of the new priests and deacons serving the largest Archdiocese in the United States! The price of the 2020-21 edition is $30.00 (shipping included). Please return your order with payment to assure processing. (As always, advertisers receive one complimentary copy, so consider advertising in next year’s edition.) Directories are scheduled to begin being mailed in October. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Please return this portion with your payment REG Archdiocese of Los Angeles 2020-2021 LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY ORDER FORM YES, send the print version of the 2020-21 ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY at the flat rate of $30.00 each. Please return your order with payment to assure processing. -

Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs

260914: Julian Filochowski Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs. It is my intuition that ‘the annunciation’ is just around the corner; that is an announcement from Rome - not from the Angel Gabriel, but from the Cardinal ‘Angel’ (Angelo) Amato, Head of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints – an announcement that our beloved Servant of God, Oscar Romero, will be raised to the altars during 2015. Oremus! Archbishop Romero is not only the most famous Salvadoran of our times, but also the most loved and simultaneously the most hated. Nevertheless it seems entirely fitting to me to adapt the words from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “he was the noblest Salvadoran of them all”. Indeed today he is recognised as such, repeatedly acclaimed by President Funes as the ‘spiritual guide of the nation’ - with monuments and memorials in almost every town and village in El Salvador. He has been described as a national treasure. As a holy prophet and martyr, Oscar Romero is, I would suggest, a precious diamond, who adds a special redemptive lustre to the universal Church of the 20th century. For over 30 years, however, Archbishop Romero’s detractors inside the Church have tried to paint a picture of him as a rather cheap fake diamond - naïve, vain, manipulated, doctrinally heterodox and politically extreme. (In truth they feared Romero’s canonisation might be interpreted as the canonisation of liberation theology.) And they are still not finished - even though their curial leader, the Colombian Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo, has now gone to that great dicastery in the sky, with God. -

In the Liberation Struggle

11 Latin Rmerican Christians inthe Liberation Struggle Since the Latin American Catholic Bishops the People's United Front. When this failed, due met in Medellin, Colombia in August and September to fragmentation and mistrust on the left and the 1968 to call for basic changes in the region, the repression exercised by the government, he joined Catholic Church has been increasingly polarized the National Liberation Army in the mountains. between those who heard their words from the He soon fell in a skirmish with government troops point of view of the suffering majorities and advised by U.S. counterinsurgency experts. those who heard them from the point of view of Camilo's option for violence has clearly affected the vested interests. The former found in the the attitudes of Latin American Christians, but Medellin documents, as in certain documents of so also has his attempt to build a United Front, the Second Vatican Council and the social ency- as we shall see in the Dominican piece which fol- clicals of Popes Paul VI and John XXIII, the lows. But more importantly, Camilo lent the fire legitimation of their struggles for justice and of committed love to the Christian forces for their condemnations of exploitation and struc- change around the continent. To Camilo it had tures of domination. The Latin American Bishops become apparent that the central meaning of his had hoped that their call published in Medellin Catholic commitment would only be found in the would be enough, all too hastily retreating from love of his neighbor. And he saw still more their public declarations when their implications clearly that love which does not find effective became apparent. -

Religion and Fake News: Faith-Based Alternative Information Ecosystems in the U.S. and Europe

Religion and Fake News: Faith-based Alternative Information Ecosystems in the U.S. and Europe Christopher Douglas | 6 January 2018 Summary he intersection of fake news and religion is marked by three asymmetries. First, fake news circulates more among Americans than Europeans. Second, fake news circulates T among conservatives more than liberals. Third, fake news for conservatives often feature religious themes. The origin of the fake news information-entertainment ecosystem lies largely in Christian fundamentalism’s cultivation of counter-expertise. The intersection of fake news and religion today is being exploited by Russia to subvert Western democracies and deepen social divisions. Western countries need to strengthen mainstream evidence-based journalism, incorporate conservative religious leaders into mainstream discussions, and detach high religiosity from fake news information ecosystems. Page 1 About the Report This report was commissioned by the Cambridge Institute on Religion & International Studies (CIRIS) on behalf of the Transatlantic Policy Network on Religion and Diplomacy (TPNRD). About the TPNRD The TPNRD is a forum of diplomats from North America and Europe who collaborate on religion-related foreign policy issues. Launched in 2015, the network is co-chaired by officials from the European External Action Service and the U.S. Department of State. About CIRIS CIRIS is a multi-disciplinary research centre at Clare College, Cambridge. CIRIS’s role as the Secretariat of the TPNRD is generously supported by the Henry Luce Foundation’s initiative on religion in international affairs. For further information about CIRIS, visit ciris.org.uk. About the Author Christopher Douglas teaches American literature and religion at the University of Victoria, Canada. -

ABCD Again Tops Goal Parish Collections...Pg

SERVING THE PEOPLE OF GOD IN THE COUNTIES OF BROWARD, COLLIER, DADE, GLADES, HENDRY, MARTIN, MONROE AND PALM BEACH Volume XXI Number 5 April 6, 1979 Price 25c ABCD Again Tops Goal Parish collections...Pg. 16 For the second year in suc- cession the Archbishop's Charities Drive has gone over the top. The goal was $3,000,000, and as of March 31, almost $3,400,000 had been pledged. This represents a 12 percent gain over the goal. Last year there was an 18 percent increase over the goal of 82,700,000. ARCHBISHOP MCCARTHY said exceeding the goal of the Charities Drive "fills me with a profound sense of gratitude and deep pride in the priests, religious and faithful of the Archdiocese. Our success reveals that we are growing as a community of love committed to living the Gospel. As your Archbishop, I marvel at the continuing generosity of our people and their dedicated spirit of service. It is with a feeling of exhilaration that I experience how the priests, religious and laity are ever-willing, in their various ministries, to respond to the call for help of those who are in need of the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. "In these days of economic and spiritual crisis, the demands are Smiles greeted the final figure of the ABCD campaign ment director, Don Livingstone, lay chairman and Msgr. ever-increasing. Your magnificent this year as Msgr. Jude O'Doherty writes the numbers John O'Dowd, coordinator of the Development office. support will help us to respond to real for Archbishop McCarthy, center, Frank Nolan, develop- needs in a tangible way. -

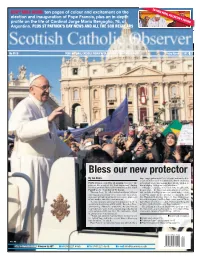

Bless Our New Protector

28-PAGE PAPAL COLLECTOR’S EDITION DON’T MISS INSIDE ten pages of colour and excitement on the election and inauguration of Pope Francis, plus an in-depth profile on the life of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 76, of Argentina. PLUS ST PATRICK’S DAY NEWS AND ALL THE SCO REGULARS No 5510 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday March 22 2013 | £1 Bless our new protector By Ian Dunn huge congregation in St Peter’s Square and watched by a vast television audience around the world, including POPE Francis called for all mankind to serve ‘the in Scotland where our bishops have already written to poorest, the weakest, the least important,’ during him pledging ‘loving and loyal obedience.’ the inauguration Mass of his ministry as the 266th Although according to Church law, he officially Pontiff on the feast day of St Joseph. became Pope—the first Jesuit and Latin American Pon- The new Pope, 76, called in his homily for ‘all men tiff, and the first Pope from a religious order in 150 and women of goodwill’ to be ‘protectors of creation, years—the minute he accepted his election in the Sis- protectors of God’s plan inscribed in nature, protectors tine Chapel on Wednesday March 13, Pope Francis was of one another and of the environment.’ formally inaugurated as Holy Father at the start of Tues- “Let us not allow omens of destruction and death to day’s Mass, when he received the Fisherman’s Ring and accompany the advance of this world,” he said on Tues- pallium, symbolising his new Papal authority. -

State Visit of H.E. Paul BIYA, President of the Republic of Cameroon, to Italy 20 - 22 March 2017

TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE PAIX REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PEACE REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL ------- ------- R E CELLULE DE COMMUNICATION R COMMUNICATION UNIT P N U EP N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER UE DU CAM State Visit of H.E. Paul BIYA, President of the Republic of Cameroon, to Italy 20 - 22 March 2017 PRESS KIT Our Website : www.prc.cm TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE PAIX REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PEACE REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL R ------- E ------- P RE N U P N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER CELLULE DE COMMUNICATION UE DU CAM COMMUNICATION UNIT THE CAMEROONIAN COMMUNITY IN ITALY - It is estimated at about 12,000 people including approximately 4.000 students. - The Cameroonian students’ community is the first African community and the fifth worldwide. - Fields of study or of specialization are: medicine (about 2800); engineering (about 400); architecture (about 300); pharmacy (about 150) and economics (about 120). - Some Cameroonian students receive training in hotel management, law, communication and international cooperation. - Cameroonian workers in Italy are about 300 in number. They consist essentially of former students practicing as doctors, pharmacists, lawyers or business executives. - Other Cameroonians with precarious or irregular status operate in small jobs: labourers, domestic workers, mechanics, etc. The number is estimated at about 1.500. 1 TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PAIX REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON PEACE Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL ------- ------- R E ELLULE DE COMMUNICATION R C P E N COMMUNICATION UNIT U P N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER UE DU CAM GENERAL PRESENTATION OF CAMEROON ameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon is History a country in the west Central Africa region.