Of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

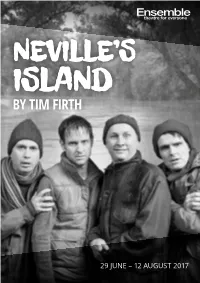

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Andrew Hansen

Andrew Hansen Comedian, musician, MC and The Chaser star Andrew Hansen is a comedian, pianist, guitarist, composer and vocalist as well as a writer and performer who is best known as a member of the Australian satirical team on ABC TV’s The Chaser. Andrew is very versatile on the corporate stage too. He can MC an event, give a custom-written comedy presentation or even compose and perform a song if inspired to do so. Andrew’s radio work includes shows on Triple M as well as composing and starring in the musical comedy series and ARIA Award winning album The Blow Parade (triple j, 2010). The Chaser’s TV shows include Media Circus (2014-15), The Hamster Wheel (2011-2013), Yes We Canberra! (2010), The Chaser’s War On Everything (2006-9), The Chaser Decides (2004, 2007) and CNNNN (2002-3). On the Seven network, Andrew produced The Unbelievable Truth (2012). He has also appeared as a guest on most Australian TV shows that have guests. In print he wrote for the humorous fortnightly newspaper The Chaser (1999-2005), eleven Chaser Annuals (Text Publishing, 2000-10), and for the recently launched Chaser Quarterly (2015). On stage Andrew composed and starred in the musical Dead Caesar (Sydney Theatre Company), did two national tours with The Chaser, and two live collaborations with Chris Taylor (One Man Show, 2014 and In Conversation with Lionel Corn, 2015). The Chaser team also runs a cool theatre in Sydney called Giant Dwarf. Andrew composed all The Chaser’s songs as well as the theme music for Media Circus and The Chaser’s War On Everything. -

Ever Thus to Tyrants

EVER THUS TO TYRANTS The plot to overthrow Julius Caesar is either treachery or an attempt to save the Republic, depending on your opinions of the figures involved. Historians have long debated whether Caesar was an accomplished leader or, as the conspirators argue, a power-hungry tyrant. What does Shakespeare’s play tell us? Legend has it that Marcus Brutus uttered “sic semper tyrannis” MARCH 2019 (“ever thus to tyrants”) as he and the other conspirators assassinated Julius Caesar. The phrase has also gained notoriety because John WRITTEN BY: Wilkes Booth allegedly shouted the phrase as he fatally shot KEE-YOON NAHM Abraham Lincoln. Booth, who at one time played Mark Antony in (FESTIVAL DRAMATURG) Shakespeare’s play, was aware of the phrase’s attribution to Brutus. He wanted to connect his murder to the death of Julius Caesar, THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT: CAESAR perhaps to justify the deed. But Brutus probably never said these words. The Roman historian Plutarch does not mention this in his account of Caesar’s life, although the assassination is described in gruesome detail. Shakespeare relied heavily on Plutarch to write his play, and so Brutus in Julius Caesar does not say the infamous line either. However, some of the other conspirators are eager to label Caesar a tyrant. Immediately after the assassination, Cinna shouts for all to hear, “Liberty! Freedom! Tyranny is dead!” By the time that Brutus and Antony give their funeral speeches, part of the public has adopted this viewpoint, calling the late Caesar a tyrant. Earlier in the play, we see Cassius first develop this narrative. -

Year 7 – Unit 3 Rhetoric and Julius Caesar

Making Meaning in English: Appendix 1 - The Art of Rhetoric Making Meaning in English: Appendix 1 Year 7 – Unit 3 Rhetoric and Julius Caesar 1 Making Meaning in English: Appendix 1 - The Art of Rhetoric Rhetoric and Julius Caesar – contents Key knowledge Rhetorical figures 4 Parts of speech 4 The three charioteers 4 The five parts of rhetoric 5 Key quotations form famous speeches 5 Characters in Julius Caesar 5 Plot of Julius Caesar 6 Key quotations from Julius Caesar 6 Section 1 The origins of rhetoric 7 Background to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar 9 Julius Caesar Act 1 scene 2 – Vocabulary in action 10 Julius Caesar Act 1 scene 2 12 Act 1 scene 2: Check your understanding 18 The first part of rhetoric: Invention 20 Alliteration 22 Rhetorical questions 24 Satan from Paradise Lost 27 Your analysis: How does Satan use rhetoric to persuade his army to support him? 28 Grammar: Auxiliary verbs in verb phrases 29 Creation – Argument 30 Section 2 The Life of Cicero 31 Julius Caesar Act 2 scene 2 – Vocabulary in action 33 Julius Caesar Act 2 scene 2: “The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes” 35 Act 2 scene 2: Check your understanding 39 The second Part of Rhetoric: Arrangement 40 Anaphora 43 Transferred epithets 45 Cicero: attack dog of the Roman Forum 47 Your analysis: How did Cicero use rhetoric to make Catiline appear guilty? 48 Grammar: Participles of the Verb 49 Creation – Argument 50 Section 3 Julius Caesar - Act 3 scene 1 – The Senate 51 Julius Caesar Act 3 scene 2 – Vocabulary in action 54 Julius Caesar Act 2 scene 2: “Lend -

Constructing Caesar: Julius Caesar’S Caesar and the Creation of the Myth of Caesar in History and Space

CONSTRUCTING CAESAR: JULIUS CAESAR’S CAESAR AND THE CREATION OF THE MYTH OF CAESAR IN HISTORY AND SPACE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bradley G. Potter, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor Fritz Graf ______________________ Professor Ellen O’Gorman Advisor Department of Greek & Latin ABSTRACT Authors since antiquity have constructed the persona of Caesar to satisfy their views of Julius Caesar and his role in Roman history. I contend that Julius Caesar was the first to construct Caesar, and he did so through his commentaries, written in the third person to distance himself from the protagonist of his work, and through his building projects at Rome. Both the war commentaries and the building projects are performative in that they perform “Caesar,” for example the dramatically staged speeches in Bellum Gallicum 7 or the performance platform in front of the temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum Iulium. Through the performing of Caesar, the texts construct Caesar. My reading aims to distinguish Julius Caesar as author from Caesar the protagonist and persona the texts work to construct. The narrative of Roman camps under siege in Bellum Gallicum 5 constructs Caesar as savior while pointing to problems of Republican oligarchic government, offering Caesar as the solution. Bellum Civile 1 then presents the savior Caesar to the Roman people as the alternative to the very oligarchy that threatens the libertas of the people. -

The English of Shakespeare : Illustrated in a Philological

'^r ^\ p Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/englisliofsliakespOOcrairicli THE English of Shakespeare; ILLDSTKATED IK ^ i^ilfllopal Cflmm^ntars JULIUS CESAR. GEORGE L. CRATK, PBOFES30B or BISTORT AND OF ENGLISH LitrrAT:JKB IJf QUSEK'S COij;.SGA, BELFAST. ^. m * . !EB£leK, from iije tirtjitts iaebigeO Honfion EDttton, BY W. J. ROLFE, KA8TEB or THE HIGH SCHOOL, CAKBBIDOB, MASS. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY EDWIN GINK WOOLWORTH, AINSWORTH, & CO. CHICAGO: FRED B. QINN. 1869. Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by CROSBY AND AINSWORTH, In the Clerk'B Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusett*. THIRD EDITION. • Tt«eOTVrt AT TN t NO. 4 SPKINO LANS. Preuwork bj John Wilson and Sob. PREFACE TO THE AMERICAN EDITION. A YEAR ago I let a class at school take yulius CcEsar as their first reading in Shakespeare, and made daily use of this book of Professor Craik's in teaching them. They noted down all the more im- portant points as I gave them, and, without having seen the book, learned the better part of it pretty thoroughly. It took more time than I had ever before given to a single play, — considerably more, of course, than would have been necessary if the book had been in the hands of the scholars ; but the results satisfied me that it was time well spent. I never had a class that became so heartily interested in Shakespeare, or that went on so rapidly and so well in reading other plays. -

Home Learning Pack Year 11 Terms 3 & 4

HOME LEARNING PACK YEAR 11 TERMS 3 & 4 1 CONTENTS How to use this pack 3 English 4 Maths - Foundation 38 Maths - Higher 86 Science 121 History 132 Geography 176 French 196 Spanish 201 Drama 214 Photography 217 Personal Development 230 Physical Education 253 2 HOW TO USE THIS BOOKLET In this booklet you will find a menu of tasks related to the subjects and topics that you study. There are opportunities for you to revise material you have previously studied, practice skills that you have learned in class and sometimes learn something new. As a minimum you will a pen and some paper to complete these tasks. If you need these, please collect from the reception desk at the academy. For some of the mind- mapping tasks you might wish to use coloured pens or pencils but they are not essential. Some tasks may ask you to create packs of flashcards. You can use any kind of paper or card for this but don’t worry if you don’t have enough, just choose another task. While you are not in school you should follow your normal school timetable and complete an hour of work for each hour you would normally be studying that subject in school. You may find that, without the support of your teacher you complete tasks more slowly than you would do in a lesson and that is absolutely fine. If you get really stuck on something, move on to the next task and/or seek help from the internet, a parent/guardian or by e-mailing or phoning your teacher if possible. -

Skenè. Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies

Σ 6:2 2020 Jewish Theatres Edited by Piero Capelli Piero Capelli – Foreword Fabrizio Lelli – Italian Jews and Theatre in Early Modern Italy Michela Andreatta – Piety on Stage: Popular Drama and the Public Life of Early Modern Jewish Confraternities Chiara Carmen Scordari – Behind Multiple Masks: Leon Modena’s Diasporic Tragedy L’Ester in Seventeenth-Century Venice Zehavit Stern – The Archive, the Repertoire, and Jewish Theatre: Zygmunt Turkow Performs a National Dramatic Heritage Yair Lipshitz – Nocturnal Histories: Nighttime and the Jewish Temporal Imagination in Modern Hebrew Drama Diego Rotman – Language Politics, Memory, and Discourse: Yiddish Theatre in Israel (1948-2003) Miscellany David Lucking – Stony Limits and Envious Walls: Metamorphosing Ovid in Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream Cristina Consiglio – Hamlet Overseas. The Acting Technique of Edwin Booth Special Section Patrick Gray – Shakespeare and the Fall of the Roman Republic: A Reply to Paul A. Cantor Elena Pellone – Will Tosh, Playing Indoors: Staging Early Modern Drama in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London and New York: Bloomsbury (The Arden Shakespeare), 2019, pp. 264 Nicola Pasqualicchio – Andrew Filmer and Juliet Rufford (eds),Performing Architectures: Projects, Practices, Pedagogies, London and New York: Methuen, 2018, pp. 235 Sally Blackburn-Daniels – A Theatrical Performance of Vernon Lee’s The Ballet of the Nations Skenè. Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 6:2 2020 Jewish Theatres Edited by Piero Capelli SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri Executive Editor Guido Avezzù. General Editors Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi.