Julius Caesar Xxxiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

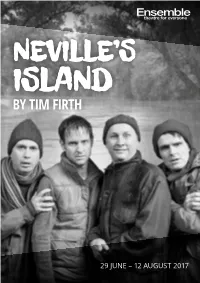

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Plutarch on the Role of Eros in a Marriage

1 2 3 4 Plutarch on the Role of Eros in a Marriage 5 6 Jeffrey Beneker 7 8 Plutarch’s thinking on marital relationships has attracted a significant amount 9 of interest in recent years and has been approached from a variety of 10 perspectives. Some scholars have studied the societal aspect of marriage in 11 Plutarch’s works, raising questions about the role of women in the household, 12 in the community, and especially in their interactions with men, and therefore 13 they have tended to address larger social issues, such as gender, sexuality, and 14 equality.1 Others have taken a philosophical tack and have examined Plutarch’s 15 writing, especially as it concerns the nature and value of marriage, in terms of 16 the broader philosophical traditions to which it is related.2 However, my focus 17 in this paper is much more narrow. I intend to explore one particular 18 component of the marital relationship itself: the erotic connection that exists, 19 or might exist, between a husband and wife. Looking first to the Moralia and 20 the dialogue Amatorius, I will argue that Plutarch describes the eros shared 21 between a married couple as an essential prerequisite for the development of 22 philia and virtue. Then, turning to the Lives, I will demonstrate how the ideas 23 found in the Amatorius are fundamental to Plutarch’s representation of 24 marriage in the biographies of Brutus and Pompey. 25 In the Amatorius, Plutarch, who is himself the principal speaker, touches on 26 a variety of topics related to eros, but the discussion itself is motivated by a 27 single event: the wealthy widow Ismenodora has expressed her desire to marry 28 the ephebe Bacchon, who comes from a family of lower social standing. -

Marcus Porcius Cato Salonianus

Marcus Porcius Cato Salonianus Marcus Porcius Cato Salonianus or Cato Salonianus (154 BC- ?) was the son of Cato the Elder by his second wife Salonia, who was the freedwoman daughter of one of Cato's own freedman scribes, formerly a slave. Centuries: 3rd century BC - 2nd century BC - 1st century BC Decades: 200s BC 190s BC 180s BC 170s BC 160s BC - 150s BC - 140s BC 130s BC 120s BC 110s BC 100s BC Years: 159 BC 158 BC 157 BC 156 BC 155 BC - 154 BC - 153 BC 152. BC Marcus Porcius Cato (Latin: M·PORCIVS·M·F·CATO[1]) (234 BC, Tusculumâ€âœ149 BC) was a Roman statesman, surnamed the Censor (Censorius), Sapiens, Priscu Marcus PORCIUS Cato Salonianus. HM George I's 59-Great Grandfather. HRE Ferdinand I's 55-Great Grandfather. Poss. Agnes Harris's 50-Great Grandfather. ` Osawatomie' Brown's 65-Great Grandfather. Wife/Partner: ? Child: Marcus Porcius Cato. _ _ _Deioneus (King) of PHOCIS +. Marcus Porcius Cato Salonianus or Cato Salonianus (154 BC- ?) was the son of Cato the Elder by his second wife Salonia, who was the freedwoman daughter of one of Cato's own freedman scribes, formerly a slave. Life. He was born 154 BC, when his father had completed his eightieth year, and about two years before the death of his half-brother, Marcus Porcius Cato Licinianus. He lost his father when he was five years old, and lived to attain the praetorship, in which office he died. [Gellius, xiii. 19.] [Plutarch, "Cato the Elder", 27.] He was father of one son also called Marcus Po.. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee. -

Pro Milone: the Purposes of Cicero’S Published Defense Of

PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. ANNIUS MILO by ROBERT CHRISTIAN RUTLEDGE (Under the Direction of James C. Anderson, Jr.) ABSTRACT This thesis explores the trial of T. Annius Milo for the murder of P. Clodius Pulcher, which occurred in Rome in 52 BC, and the events leading up to it, as well as Marcus Tullius Cicero’s defense of Milo and his later published version of that defense. The thesis examines the purposes for Cicero’s publication of the speech because Cicero failed to acquit his client, and yet still published his defense. Before specifically examining Cicero’s goals for his publication, this thesis considers relationships between the parties involved in the trial, as well as the conflicting accounts of the murder; it then observes the volatile events and novel procedure surrounding the trial; and it also surveys the unusual topographic setting of the trial. Finally, this thesis considers the differences between the published speech and the speech delivered at trial, the timing of its publication, and possible political and philosophical purposes. INDEX WORDS: Marcus Tullius Cicero, Pro Milone, Titus Annius Milo, Publius Clodius Pulcher, Pompey, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Quintus Asconius Pedianus, Roman Courts, Roman Trials, Roman Criminal Procedure, Ancient Criminal Procedure, Roman Rhetoric, Latin Rhetoric, Ancient Rhetoric, Roman Speeches, Roman Defense Speeches, Roman Topography, Roman Forum, Roman Philosophy, Roman Stoicism, Roman Natural Law, Roman Politics PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. ANNIUS MILO by ROBERT CHRISTIAN RUTLEDGE B.A. Philosophy, Georgia State University, 1995 J.D., University of Georgia, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Robert Christian Rutledge All Rights Reserved PRO MILONE: THE PURPOSES OF CICERO’S PUBLISHED DEFENSE OF T. -

Marcus Junius Brutus David B

History Publications History 2007 Marcus Junius Brutus David B. Hollander Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_pubs Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Political History Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ history_pubs/6. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marcus Junius Brutus Abstract Marcus Junius Brutus (BREW-tuhs) came from noble stock. His reputed paternal ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, helped overthrow the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, in 510 B.C.E. and then became one of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic. His mother, Servilia Caepionis, was descended from Gaius Servilius Ahala, who had murdered the would-be tyrant Spurius Maelius in 439. Disciplines Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity | Political History Comments "Marcus Junius Brutus," in Great Lives from History: Notorious Lives, ed. Carl L. Bankston III, Salem Press (2007) 146-148. Used with permission of EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_pubs/6 Great Lives from History: Notorious Lives Marcus Junius Brutus by David B. -

Andrew Hansen

Andrew Hansen Comedian, musician, MC and The Chaser star Andrew Hansen is a comedian, pianist, guitarist, composer and vocalist as well as a writer and performer who is best known as a member of the Australian satirical team on ABC TV’s The Chaser. Andrew is very versatile on the corporate stage too. He can MC an event, give a custom-written comedy presentation or even compose and perform a song if inspired to do so. Andrew’s radio work includes shows on Triple M as well as composing and starring in the musical comedy series and ARIA Award winning album The Blow Parade (triple j, 2010). The Chaser’s TV shows include Media Circus (2014-15), The Hamster Wheel (2011-2013), Yes We Canberra! (2010), The Chaser’s War On Everything (2006-9), The Chaser Decides (2004, 2007) and CNNNN (2002-3). On the Seven network, Andrew produced The Unbelievable Truth (2012). He has also appeared as a guest on most Australian TV shows that have guests. In print he wrote for the humorous fortnightly newspaper The Chaser (1999-2005), eleven Chaser Annuals (Text Publishing, 2000-10), and for the recently launched Chaser Quarterly (2015). On stage Andrew composed and starred in the musical Dead Caesar (Sydney Theatre Company), did two national tours with The Chaser, and two live collaborations with Chris Taylor (One Man Show, 2014 and In Conversation with Lionel Corn, 2015). The Chaser team also runs a cool theatre in Sydney called Giant Dwarf. Andrew composed all The Chaser’s songs as well as the theme music for Media Circus and The Chaser’s War On Everything.