Ever Thus to Tyrants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

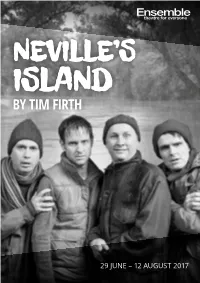

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

The Americans

INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1861. Seven Southern states have seceded from the Union over the issues of slavery and states rights. They have formed their own government, called the Confederacy, and raised an army. In March, the Confederate army attacks and seizes Fort Sumter, a Union stronghold in South Carolina. President Lincoln responds by issuing a call for volun- teers to serve in the Union army. Can the use of force preserve a nation? Examine the Issues • Can diplomacy prevent a war between the states? • What makes a civil war different from a foreign war? • How might a civil war affect society and the U.S. economy? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 11 links for more information about The Civil War. 1864 The 1865 Lee surrenders to Grant Confederate vessel 1864 at Appomattox. Hunley makes Abraham the first successful Lincoln is 1865 Andrew Johnson becomes submarine attack in history. reelected. president after Lincoln’s assassination. 1863 1864 1865 1864 Leo Tolstoy 1865 Joseph Lister writes War and pioneers antiseptic Peace. surgery. The Civil War 337 The Civil War Begins MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names The secession of Southern The nation’s identity was •Fort Sumter •Shiloh states caused the North and forged in part by the Civil War. •Anaconda plan •David G. Farragut the South to take up arms. •Bull Run •Monitor •Stonewall •Merrimack Jackson •Robert E. Lee •George McClellan •Antietam •Ulysses S. Grant One American's Story On April 18, 1861, the federal supply ship Baltic dropped anchor off the coast of New Jersey. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

Abraham Lincoln Official Bicentennial Publication State Participation: Virginia

Abraham Lincoln official Bicentennial Publication State Participation: Virginia 1. Name of state: Virginia 2. State motto: "Sic Semper Tyrannis" (Thus Always to Tyrants) 3. Governor's message: On behalf of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia, I am honored to pay tribute to one of America’s greatest leaders. Our nation’s proud history serves as an enduring testament to the fortitude and resolve of Abraham Lincoln. The experiment of American democracy faced a vital test as Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office as its sixteenth president. No American leader since Virginia’s own George Washington had taken the helm of the United States with such a challenge, as Lincoln would phrase it: such a “house divided.” Yet as his term and his brief life came to a close, Lincoln wiped the injustice of slavery from American society, restored the Union and brought us one step closer to the realization of the ideals upon which the country was founded. Although Lincoln is a son of Illinois, we in Virginia claim him as a brother. Lincoln has extensive family ties to the Commonwealth – his great-grandparents and grandparents lived in Virginia and his parents met, married, and lived for a time in the Shenandoah Valley. In Virginia, we claim Lincoln as a brother not just because his roots here run deep. Throughout his life, Lincoln exhibited the best qualities of Virginians. He embodied the courage of the Jamestown settlers and of two of his predecessors, Washington and Jefferson. Lincoln devoted himself to breaking the bonds that divided communities and his influence echoed in the twentieth century through the life of legal pioneer Oliver Hill. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

Ford's Theatre, Lincoln's Assassination and Its Aftermath

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/education/landmarks-american-history- and-culture-workshops-school-teachers for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Seat of War and Peace: The Lincoln Assassination and Its Legacy in the Nation’s Capital Institution: Ford’s Theatre Project Directors: Sarah Jencks and David McKenzie Grant Program: Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops 400 7th Street, S.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 2. Narrative Description 2015 will mark the 150th anniversary of the first assassination of a president—that of President Abraham Lincoln as he watched the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, six blocks from the White House in Washington, D.C. -

The Unitary Executive During the Second Half-Century

THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE DURING THE SECOND HALF-CENTURY * STEVEN G. CALABRESI ** CHRISTOPHER S. YOO I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................668 II. THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE DURING THE JACKSONIAN PERIOD, 1837-1861 .........................669 A. Martin Van Buren .................................................670 B. William H. Harrison ..............................................678 C. John Tyler...............................................................682 D. James K. Polk..........................................................688 E. Zachary Taylor.......................................................694 F. Millard Fillmore.....................................................698 G. Franklin Pierce.......................................................704 H. James Buchanan .....................................................709 III. THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE DURING THE CIVIL WAR, 1861-1869 ..................................717 A. Abraham Lincoln....................................................718 B. Andrew Johnson.....................................................737 C. The Tenure of Office Act and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson .................................................746 IV. THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE DURING THE GILDED AGE, 1869-1889................................759 A. Ulysses S. Grant ....................................................759 B. Rutherford B. Hayes...............................................769 C. James A. Garfield....................................................780 D. Chester