Zoroaster : the Prophet of Ancient Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

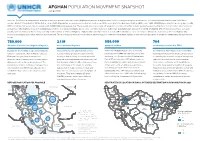

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

2 Religions and Religious Movements

ISBN 978-92-3-103654-5 Introduction 2 RELIGIONS AND RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS H.-J. Klimkeit, R. Meserve, E. E. Karimov and C. Shackle Contents Introduction ....................................... 62 RELIGIONS IN THE CENTRAL ASIAN ENVIRONMENT ............. 67 Turkic and Mongol beliefs, the Tibetan Bon religion and shamanism ......... 67 Religion among the Uighurs, Kyrgyz, Kitan ...................... 69 MANICHAEISM AND NESTORIAN CHRISTIANITY ............... 71 Manichaeism ...................................... 71 Nestorian Christianity .................................. 75 Zoroastrianism ..................................... 78 Hinduism ........................................ 82 THE ADVENT OF ISLAM: EXTENT AND IMPACT ................ 83 NON-ISLAMIC MYSTIC MOVEMENTS IN HINDU SOCIETY .......... 88 The Hatha-yoga movement ............................... 89 The bhakti movement .................................. 90 Birth of the Sikh religion ................................ 91 Introduction (H.-J. Klimkeit) Although cultural and religious life along the Central Asian Silk Route was determined both by various indigenous traditions, including Zoroastrianism, and by the world 62 ISBN 978-92-3-103654-5 Introduction religions that expanded into this area from India and China as well as from Syria and Per- sia, we can detect certain basic patterns that recur in different areas and situations.1 Here we mainly wish to illustrate that there were often similar geopolitical and social conditions in various oasis towns. The duality of such towns and the surrounding deserts, steppes and mountains is characteristic of the basic situation. Nomads dwelling in the steppes had their own social structures and their own understanding of life, which was determined by tra- ditions that spoke of forefathers and heroes of the past who had created a state with its own divine orders and laws. The Old Turkic inscriptions on the Orkhon river in Mongolia are a good case in point. -

A Sacred Celestial Motif: an Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Mazloumi & Nasrollahzadeh, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 2, pp. 682 - 699 Date of Publication: 16th September, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.32.682699 This paper can be cited as: Mazloumi, Y., & Nasrollahzadeh, C. (2017). A Sacred Celestial Motif: An Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(2), 682-699. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. A SACRED CELESTIAL MOTIF: AN INTRODUCTION TO WINGED ANGELS ICONOGRAPHY IN IRAN Yasaman Nabati Mazloumi M.A in Iranian Studies, Shahid Beheshti University, Daneshjoo Blvd, Velenjak, Street, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Cyrus Nasrollahzadeh Associate Professor, Department of Ancient Iranian Culture and Languages, Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 64th Street, Kurdestan Expressway, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract Through history many motifs have been created and over the centuries, some of them turned into very well-known symbols. One of these motifs is winged angel. This sacred and divine creature which appears in human-shaped, serves intermediaries between the God and people, and during history, indicates legitimating and bestows God-given glory. This article aims to present the results of exploring the historical background of the winged angels in Iran, in order to understand its precise concept; where it comes from and what it resembles. -

De Oud-Germaanse Religie (§§ 570 - 598) (De Vries) 1

Dit document vormt een onderdeel van de website https://www.religies-overzichtelijk.nl Hier vindt u tevens de koppelingen naar de andere teksten en de indexen, de toelichtingen en de afkortingen Laatste bewerking: 26-09-2020 [l] De Oud-Germaanse religie (§§ 570 - 598) (De Vries) 1 1 De schepping van de wereld en de mensen volgens de Germaanse overlevering .............. 4 1.1 (§ 570-6) Inleiding tot de schepping van de wereld en de mensen volgens de Germaanse overlevering .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 De scheppingsmythen ..................................................................................... 6 1.2.1 De mythe van Ýmir (SnE) ........................................................................... 7 1.2.1.1 (§ 570-1) Episode 1: de toestand vóór de schepping en het onstaan van Ýmir ........ 8 1.2.1.2 (§ 570-2) Episode 2: Auðumla en de schepping der goden ................................ 9 1.2.1.3 (§ 570-3) Episode 3: de slachting van Ýmir en de schepping van de wereld ......... 10 1.2.2 (§ 570-4) De mythe van de schepping van Askr en Embla (SnE) ........................... 11 1.2.3 (§ 570-5) De mythe van Odins vestiging in Ásgarðr (SnE) ................................... 12 1.3 De toestand vóór de schepping ....................................................................... 13 1.3.1 (§ 571-1) De toestand vóór de schepping in de literatuur .................................. 14 1.3.2 (§ 571-2) Verklaring van de overlevering t.a.v. de toestand vóór de schepping ....... 15 1.4 (§ 572) Het ontstaan van leven uit de polariteit van hitte en koude ........................... 16 1.5 (§ 573) De schepping van reuzen, goden en mensen uit een tweegeslachtelijk oerwezen 17 1.6 (§ 574) De voorstelling van de melk schenkende oerkoe ......................................... 18 1.7 (§ 575) De schepping van de wereld uit het lichaam van Ýmir ................................. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction

CHAPTER TEN: ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction A. Zoroastrianism: One of the World’s Oldest Living Religions B. Possesses Only 250,000 Adherents, Most Living in India C. Zoroastrianism Important because of Influence of Zoroastrianism on Christianity, Islam, Middle Eastern History, and Western Philosophy II. Pre-Zoroastrian Persian Religion A. The Gathas: Hymns of Early Zoroastrianism Provide Clues to Pre- Zoroastrian Persian Religion 1. The Gathas Considered the words of Zoroaster, and are Foundation for all Later Zoroastrian Scriptures 2. The Gathas Disparage Earlier Persian Religions B. The Aryans (Noble Ones): Nomadic Inhabitants of Ancient Persia 1. The Gathas Indicate Aryans Nature Worshippers Venerating Series of Deities (also mentioned in Hindu Vedic literature) a. The Daevas: Gods of Sun, Moon, Earth, Fire, Water b. Higher Gods, Intar the God of War, Asha the God of Truth and Justice, Uruwana a Sky God c. Most Popular God: Mithra, Giver and Benefactor of Cattle, God of Light, Loyalty, Obedience d. Mithra Survives in Zoroastrianism as Judge on Judgment Day 2. Aryans Worship a Supreme High God: Ahura Mazda (The Wise Lord) 3. Aryan Prophets / Reformers: Saoshyants 97 III. The Life of Zoroaster A. Scant Sources of Information about Zoroaster 1. The Gathas Provide Some Clues 2. Greek and Roman Writers (Plato, Pliny, Plutarch) Comment B. Zoroaster (born between 1400 and 1000 B.C.E.) 1. Original Name (Zarathustra Spitama) Indicates Birth into Warrior Clan Connected to Royal Family of Ancient Persia 2. Zoroaster Becomes Priest in His Religion; the Only Founder of a World Religion to be Trained as a Priest 3. -

Elbrus 5642M (South) - Russia

Elbrus 5642m (South) - Russia & Damavand 5671m - Iran EXPEDITION OVERVIEW Mount Elbrus and Mount Damavand Combo In just two weeks this combo expedition takes you to the volcanoes of Damavand in Iran, which is Asia’s highest, and Elbrus in Russia, which is Europe’s highest. On Elbrus we gradually gain height and increase our chance of success by taking time to acclimatise in the Syltran-Su valley on Mount Mukal, which offers views across the beautiful valleys to Elbrus. Once acclimatised, we climb these sweeping snow slopes to the col between Elbrus’ twin summits before continuing easily to the true summit of Europe’s highest mountain in an ascent of about 1000m. A brief celebration and then we fly direct to Tehran where Mount Damavand may be little known outside its home nation of Iran but it is Asia’s highest volcano and provides a delightful challenge for mountaineers. It is located northeast of Tehran, close to the Caspian Sea and dominates the Alborz mountain range. Damavand is, with its near-symmetrical lines, a beautiful and graceful peak that has lain dormant for 10,000 years. On reaching the crater rim you walk around it to the true summit and it is possible to walk into the crater. It is technically easy but demands a good level of fitness. PLEASE NOTE – YOU WILL NEED TO BOOK THIS TRIP AT LEAST 3 MONTHS BEFORE THE DEPARTURE DATE, TO ALLOW TIME TO GET YOUR AUTHORISATION CODE AND VISA FOR IRAN. The Volcanic Seven Summits Challenge – your dream met, a worldwide journey to the seven continents with a unique challenge that has only been completed by a handful of people. -

Pahlavica Iii)(1)

SOME REMARKS ON KARDER'S INSCRIPTION OF THE KA'BE-YE ZARDOST (PAHLAVICA III)(1) GIKYO ITO Prof. Emer. of Kyoto University Since its finding in 1939, Karder's Inscription of the Ka`be-ye Zardost (KKZ)(2) has invited various discussions linguistic or religio-historical and much ingenuity has been spent in trying to solve the difficulties. Thus some of them have been solved,(3) but some are not and sometimes strange miscal- culations still prevail in their treatments. KKZ begins with the wording: W; NH kltyr ZY mgwpt yzd'n W shpwhry MLK;n KLK; hwplst'y W hwk'mky HWYTNn. ;P-m PWN ZK sp'sy ZY-m PWN yzd'n W shpwhry MLK;n MLK; klty-HWYTNt-ZK-m;BYDWN shpwhry MLK;n MLK; PWN kltk'n ZY yzd'n PWN BB; W stly ;L stly gyw'k ;L gyw'k h'mstly PWN mgwstn k'mk'ly W p'ths'y (line 1)=ud 'az Karder 'i mowbed yazdan ud sabuhr 'sahan 'sah huparista ud hukamag HWYTNn ('niwehan). u-m 'pad 'an spas 'i-m 'pad yazdan ud sabuhr 'sahan 'sah 'kard-HWYTNt ('niwehed)-ZK-m ('a-m) 'kard Sabuhr 'sahan 'sah 'pad kardagan 'i yazddn 'pad 'dar ud sahr 'o sahr gydg 'o gyag hamsahr 'pad mowestankamgar ud padixsa (line 1). In this prologue, there are two problematic words: one is HWYTN-and the other ZK-m. (1) In regard to HWYTN-: Two forms provided with respective pho- netic complement -n and -t are here employed in distinction to KNRm where (lines 1 and 2) the only form HWYTN occurs for them both. -

The Majority of the Mithraic Monuments And

THE ORIGINS OF MITHRAIC MYSTERIES AND THE IDEA OF PROTO-MITHRAISM In Memory of the late Professor Osamu Suzuki (1905-1977) HIDEO OGAWA Professor, Keio University I The majority of the Mithraic monuments and inscriptions have been known from the western half of the Roman Empire.(1) The eastern half, includ- ing Greece, the Near East, North Africa, Egypt and South Russia, have given less evidences. This would not be so surprising, if Mithras had been a native god of the Romans or of a western province. But such is not the case. With the exception of S. Wikander,(2) most scholars have supported the eastern origin of the god Mithras and his mystery cult. This thesis was stated in the most typical way by Franz Cumont.(3) His speculations have been the starting point of almost all subsequent Mithraic studies. I do not want to re- capitulate his theory in length here, but confine myself in describing the main line of it with an emphasis upon his methodology concerning the problem of Mithraic origins. According to Cumont, the Avestan origin of Mithras is obvious. In the days of the Persian empire, magi (perhaps with official support) transplanted from Iran the worship of Mithras and Anahita in Asia Minor, North Syria and Armenia. Anahita was identified there with various local mother godesses such as Cybele. The cult of Mithras at first absorbed the astronomical ideas in Mesopotamia as the monuments of Nemrud-Dagh so indicate. Then, later, under the Greek influence in the Hellenistic period the cult was organized as an independent sectarian reli- gion. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

Final Qualifacition Paper

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN TERMEZ STATE UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HISTORY FINAL QUALIFACITION PAPER On the theme: ‘‘ INTERPRETATION OF ZARAOSTRIANISM SAINTS IN WRITTEN AN MATERIAL SOURCES ’’ Done by: 4th course student of the faculty of History O. X. Parmonov ____________ SUPERVIOR: SH.B. Abdulloyev __________ The Final Qualification Work is preliminary discussed in the faculty of History. Termez-2016 1 C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………...….........3-12 CHAPTER I. A SCIENTIFIC-THEORETICAL COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE ZOROASTRIANISM..............………..…….…………...…………. 12-20 1. The history of zoroastrianism........................……………..….... 12-14 2. Avesta and avestology................................................................... 15-20 CHAPTER II. ZOROASTRIANISM DIVINITES AS A SCIENTIFIC PROBLEM ...........……………………………….…..………………....21-77 1. Zoroastrianism deities in the analysis of written sources......... 21-65 2. The iconagraphy of zoroastrianism divinites..…….…............... 66-77 CONCLUSION............................ 78-80 BIBLIOGRAPHY.........................81-84 2 INTRODUCTION The Culimination of theme: Obviously, Avesta valuable encyclopedic resource reflecting the view of the world of our ancestors. He is the world itself all the philosophical doctrines effect. However, history of painful tests, "Avesta" is also avoided. Nearly a quarter of the village's only (four of 21 books). Unfortunately, parts of the source text are also not free from the effects of time. For this reason, studies conducted by historians today, but he was the only conclusions, including where the subscription is based on the opinions of scientific hypotheses. The birthplace of Zoroaster and Zaratushtraning historians seem to be the end of the chapter. As part of this final qualifying of his native gods, or image, the emergence and development although it is impossible to clarify that, on the basis of research in this area in recent years, foreign languages have been expressed in terms of the students.