Tanka E O Sentimento Dos Japoneses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

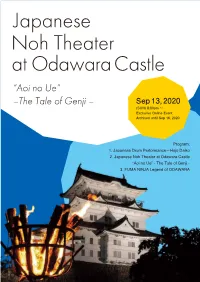

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

The Reflection of the Concept of Marriage of Heian Japanese Aristocracy Revealed in Murasaki Shikibu's

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI v PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Yunita Prabandari Nomor Mahasiswa : 084214081 Demi pengembangan ilmu -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

The Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Tale of Genji and a Dream of Red Mansions

Volume 5, No. 2-3 24 The Cross-cultural Comparison of The Tale of Genji and A Dream of Red Mansions Mengmeng ZHOU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China; Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Tale of Genji, and A Dream of Red Mansions are the classic work of oriental literature. The protagonists Murasaki-no-ue and Daiyu, as the representatives of eastern ideal female images, reflect the similarities and differences between Japanese culture and Chinese culture. It is worthwhile to elaborate and analyze from cross-cultural perspective in four aspects: a) the background of composition; b)the psychological character; c) the cultural aesthetic orientation; and d)value orientation. Key Words: Murasaki-no-ue; Daiyu; cross-cultural study 1. THE BACKGROUND OF COMPOSITION The Tale of Genji, is considered to be finished in its present form between about 1000 and 1008 in Heian-era of Japan. The exact time of final copy is still on doubt. The author Murasaki Shikibu was born in a family of minor nobility and a member the northern branch of the Fujiwara clan. It is argued that her given name might have been Fujiwara Takako. She had been a maid of honor in imperial court. As a custom in imperial court, the maid of honor was given an honorific title by her father or her brother‘s position. ―Shikibu‖ refers to her elder brother‘s position in the Bureau of Ceremony (shikibu-shō).―Murasaki‖ is her nickname, which is called by the readers, after the character Murasaki-no-ue in The Tale of Genji. -

The Tale of Murasaki Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE TALE OF MURASAKI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Liza Dalby | 448 pages | 21 Aug 2001 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780385497954 | English | New York, United States The Tale of Murasaki PDF Book There is no way I could have written a scholarly biography or history of her because there are too many gaps. Their mother died, perhaps in childbirth, when they were quite young. These items are shipped from and sold by different sellers. Dalby definitely has a flair for writing like a Japanese person; her images of nature are beautiful and harmonious and lucidly flow page after page and yet the reader develops a sense of what a strong woman Murasaki was, flawed and often sarcastic. My own career at court was developing moderately well, and I was then under the protection of Counselor Kanetaka, a nephew of Regent Michinaga. Is there a difference in style between the last chapter and the rest of the novel? Anyone already an enthusiast either of [The Tale of] Genji or of Arthur Golden's wonderful Memoirs of a Geisha will already be running to the bookstore for this book Archived from the original on August 2, Designated one of the One Hundred Poets , Murasaki is shown dressed in a violet kimono , the color associated with her name, in this Edo period illustration. The endorsement from Arthur Golden of Memoirs of a Geisha infamy already lowered my expectations. The atmosphere was so vividly painted, I really felt like I got a good idea of the life she lead. The complexities of the style mentioned in the previous section make it unreadable by the average Japanese person without dedicated study of the language of the tale. -

The Tale of Genji” and Its Selected Adaptations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Anna Kuchta Instytut Filozo!i, Uniwersytet Jagielloński Joanna Malita Instytut Religioznawstwa, Uniwersytet Jagielloński Spirit possession and emotional suffering in „The Tale of Genji” and its selected adaptations. A study of love triangle between Prince Genji, Lady Aoi and Lady Rokujō Considered a fundamental work of Japanese literature – even the whole Japanese culture – !e Tale of Genji, written a thousand years ago by lady Murasaki Shikibu (a lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court of the empress Shōshi1 in Heian Japan2), continues to awe the readers and inspire the artists up to the 21st century. %e amount of adaptations of the story, including more traditional arts (like Nō theatre) and modern versions (here !lms, manga and anime can be mentioned) only proves the timeless value and importance of the tale. %e academics have always regarded !e Tale of Genji as a very abundant source, too, as numerous analyses and studies have been produced hitherto. %is article intends to add to the perception of spiri- tual possession in the novel itself, as well as in selected adaptations. From poems to scents, from courtly romance to political intrigues: Shikibu covers the life of aristocrats so thoroughly that it became one of the main sour- ces of knowledge about Heian music3. Murasaki’s novel depicts the perfect male, 1 For the transcript of the Japanese words and names, the Hepburn romanisation system is used. %e Japanese names are given in the Japanese order (with family name !rst and personal name second). -

Poetry: the Language of Love in Tale of Genji

Poetry: The Language of Love in Tale of Genji YANPING WANG This article examines the poetic love presented by waka poetry in the Tale of Genji. Waka poetry comprises the thematic frame of Tale of Genji. It is the language of love. Through observation of metaphors in the waka poems in this article, we can grasp the essence of the poetics of love in the Genji. Unlike the colors of any heroes’ and heroines’ love in other literary works, Genji’s love is poetic multi-color, which makes him a mythopoetic romantic hero in Japanese culture. Love in Heian aristocracy is sketched as consisting of an elaborate code of courtship which is very strict in its rules of communion by poetry. Love is a romantic adventure without compromise and bondage of morality. The love adventure of Genji and other heroes involves not only aesthetic Bildung and political struggle but also poetic production and metaphorical transformation. The acceptance of the lover’s poetic courtship creates an artistic and romantic air to the relations between men and women. Love and desire are accompanied by a ritual of elegance, grace and a refined cult of poetic beauty. There are 795 poems (waka) in the Genji. They are used in the world of the Genji as a medium of interpersonal communication, as a means to express individual emotions and feelings, as an artistic narrative to poeticize the romance and as an artistic form to explore the internal life of the characters.1 Nearly 80 percent (624) of these 795 poems are exchanges (zotoka), 107 are solo recitals and 64 are occasional poems.2 -

Sowon S. Park

Journal of World Literature Volume 1 Number 2, 2016 The Chinese Scriptworld and World Literature Guest-editor: Sowon S. Park Journal of World Literature (1.2), p. 0 The Chinese Scriptworld and World Literature CONTENTS Introduction: Transnational Scriptworlds Sowon S. Park … 1 Scriptworlds Lost and Found David Damrosch … 13 On Roman Letters and Other Stories: An Essay in Heterographics Charles Lock … 28 The Chinese Script in the Chinese Scriptworld: Chinese Characters in Native and Borrowed Traditions Edward McDonald … 42 Script as a Factor in Translation Judy Wakabayashi … 59 The Many Scripts of the Chinese Scriptworld, the Epic of King Gesar, and World Literature Karen L. Thornber … 79 Eating Murasaki Shikibu: Scriptworlds, Reverse-Importation, and the Tale of Genji Matthew Chozick … 93 From the Universal to the National: The Question of Language and Writing in Twentieth Century Korea Lim HyongTaek … 108 Cultural Margins, Hybrid Scripts: Bigraphism and Translation in Taiwanese Indigenous Writing Andrea Bachner … 121 The Twentieth Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic John Duong Phan … 140 Journal of World Literature (1.2), p. 1 The Chinese Scriptworld and World Literature Introduction: Transnational Scriptworlds Sowon S. Park Oxford University [email protected] The Chinese Scriptworld and World Literature This special issue brings into focus the “Chinese scriptworld,” the cultural sphere inscribed and afforded by Chinese characters. Geographically, it stretches across China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, all of which use, or have used, Chinese characters with which to write. This region has long been classified in Western as well as East Asian scholarship as the East Asian Cultural Sphere, the Sinosphere, or the Sinographic sphere. -

The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Literature: a Spring Rain

The Lotus Sutra in Japanese literature: A spring rain This is a translation of a Spanish lecture presented on 12 April 2013 at the SGISpain Culture Center in RivasVaciamadrid, near Madrid Carlos Rubio ILL I be able, in little over an hour, to enumerate the properties of Wwater to you? And its benefits for the soil and the land? It would be better to sum it all up in one sentence which we have probably heard more than once: “Water is the key to life on earth”. To me, in this day of spring here in Madrid, lavish in fresh and unexpected downpours, beautifully referred to as “harusame” by Japanese people, the water is a metaphor for the Lotus Sutra. I am not going to explain this metaphor in terms of what this text stands for to the Buddhist believer. I do not have the authority to it simply because, unlike most, if not all of you, I am not gifted with faith. However, I would venture to talk about the Lotus Sutra—and I ask you to pardon me for being daring—due to its intrinsic values, as I perceive them, through what I learnt during the two years of supervision of the text, when I had the honour of collaborating in the Spanish edition of the work which Soka Gakkai is preparing, as well as its connection with some aspects of the Japanese culture, especially poetry. Message of Hope: “You will be Buddhas” In the first scene of the Lotus Sutra (abbreviated from now on as LS)1, great sages, deities and kings gather in large numbers to hear the Buddha speaking.