Title on the Tale of Genji and the Art of Translation Sub Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations Janice Shizue Kanemitsu In seventeenth-century Japan, dramatic narratives were being performed under drastically new circumstances. Instead of itinerant performers giving performances at religious venues in accordance with a ritual calendar, professionals staged plays at commercial, secular, and physically fixed venues. Theaters contracted artists to perform monthly programs (that might run shorter or longer than a month, depending on a given program’s popularity and other factors) and operated on revenues earned by charging theatergoers admission fees. A theater’s survival thus hinged on staging hit plays that would draw audiences. And if a particular cast of characters was found to please crowds, producing plays that placed the same characters in a variety of situations was one means of ensuring a full house. Kinpira jōruri 金平浄瑠璃 enjoyed tremendous though short-lived popularity as a form of puppet theater during the mid-1600s. Though its storylines lack the nuanced sophistication of later theatrical narra- tives, Kinpira jōruri offers a vivid illustration of how theater interacted with publishing in Japan during the early Tokugawa 徳川 period. This essay begins with an overview of Kinpira jōruri’s historical background, and then discusses the textualization of puppet theater plays. Although Kinpira jōruri plays were first composed as highly masculinized period pieces revolving around political scandals, they gradually transformed to incorporate more sentimentalism and female protagonists. The final part of this chapter will therefore consider the fundamental characteristics of Kinpira jōruri as a whole, and explore the ways in which the circulation of Kinpira jōruri plays—as printed texts— encouraged a transregional hybridization of this theatrical genre. -

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Title the NEW ECONOMIC POLICY in the CLOSING DAYS of the TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE Author(S) Honjo, Eijiro Citation Kyoto University Ec

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository THE NEW ECONOMIC POLICY IN THE CLOSING DAYS Title OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE Author(s) Honjo, Eijiro Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1929), 4(2): 52-75 Issue Date 1929-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/125185 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 1 Kyoto University Economic Review MEMOIRS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN THE IMPERIAL. UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO VOLUME IV 1929 PUBUSIIED bY THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN 'fHR IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO THE NEW ECONOMIC POLICY IN THE CLOSING DAYS OF THE TOKUGAW A SHOGUNATE The period of about 260 years following the Keicho and Genna eras (1596-1623) is called either the Tokugawa period or the age of the feudal system based on the centralisation of power; but, needless to say, the situation in this period, as in other periods, was subject to a variety of changes. Especially in and after the middle part of the Tokugawa Shogunate, commerce and industry witnessed considerable development, currency was widely circulated and the chanin class, or commercial interests, gained much influence in consequence of the growth of urban districts. This led to the development of the currency economy in addition to the land economy already existing, a new economic power thus coming into being besides the agrarian economic power. Owing to this remarkable economic change, it became im· possible for the samurai class to maintain their livelihood, and for the farming class to support the samurai class as under the old economic system, with the result that these classes had to bow to the new economic power and look to the chiinin for financial help. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

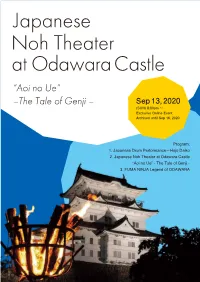

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

The Reflection of the Concept of Marriage of Heian Japanese Aristocracy Revealed in Murasaki Shikibu's

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI v PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Yunita Prabandari Nomor Mahasiswa : 084214081 Demi pengembangan ilmu -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

The Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Tale of Genji and a Dream of Red Mansions

Volume 5, No. 2-3 24 The Cross-cultural Comparison of The Tale of Genji and A Dream of Red Mansions Mengmeng ZHOU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China; Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Tale of Genji, and A Dream of Red Mansions are the classic work of oriental literature. The protagonists Murasaki-no-ue and Daiyu, as the representatives of eastern ideal female images, reflect the similarities and differences between Japanese culture and Chinese culture. It is worthwhile to elaborate and analyze from cross-cultural perspective in four aspects: a) the background of composition; b)the psychological character; c) the cultural aesthetic orientation; and d)value orientation. Key Words: Murasaki-no-ue; Daiyu; cross-cultural study 1. THE BACKGROUND OF COMPOSITION The Tale of Genji, is considered to be finished in its present form between about 1000 and 1008 in Heian-era of Japan. The exact time of final copy is still on doubt. The author Murasaki Shikibu was born in a family of minor nobility and a member the northern branch of the Fujiwara clan. It is argued that her given name might have been Fujiwara Takako. She had been a maid of honor in imperial court. As a custom in imperial court, the maid of honor was given an honorific title by her father or her brother‘s position. ―Shikibu‖ refers to her elder brother‘s position in the Bureau of Ceremony (shikibu-shō).―Murasaki‖ is her nickname, which is called by the readers, after the character Murasaki-no-ue in The Tale of Genji. -

<全文>Japan Review : No.34

<全文>Japan review : No.34 journal or Japan review : Journal of the International publication title Research Center for Japanese Studies volume 34 year 2019-12 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1368/00007405/ 2019 PRINT EDITION: ISSN 0915-0986 ONLINE EDITION: ISSN 2434-3129 34 NUMBER 34 2019 JAPAN REVIEWJAPAN japan review J OURNAL OF CONTENTS THE I NTERNATIONAL Gerald GROEMER A Retiree’s Chat (Shin’ya meidan): The Recollections of the.\ǀND3RHW+H]XWVX7ǀVDNX R. Keller KIMBROUGH Pushing Filial Piety: The Twenty-Four Filial ExemplarsDQGDQ2VDND3XEOLVKHU¶V³%HQH¿FLDO%RRNVIRU:RPHQ´ R. Keller KIMBROUGH Translation: The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars R 0,85$7DNDVKL ESEARCH 7KH)LOLDO3LHW\0RXQWDLQ.DQQR+DFKLUǀDQG7KH7KUHH7HDFKLQJV Ruselle MEADE Juvenile Science and the Japanese Nation: 6KǀQHQ¶HQDQGWKH&XOWLYDWLRQRI6FLHQWL¿F6XEMHFWV C ,66(<ǀNR ENTER 5HYLVLWLQJ7VXGD6ǀNLFKLLQ3RVWZDU-DSDQ³0LVXQGHUVWDQGLQJV´DQGWKH+LVWRULFDO)DFWVRIWKH.LNL 0DWWKHZ/$5.,1* 'HDWKDQGWKH3URVSHFWVRI8QL¿FDWLRQNihonga’s3RVWZDU5DSSURFKHPHQWVZLWK<ǀJD FOR &KXQ:D&+$1 J )UDFWXULQJ5HDOLWLHV6WDJLQJ%XGGKLVW$UWLQ'RPRQ.HQ¶V3KRWRERRN0XUǀML(1954) APANESE %22.5(9,(:6 COVER IMAGE: S *RVRNXLVKLNLVKLNL]X御即位式々図. TUDIES (In *RVRNXLGDLMǀVDLWDLWHQ]XDQ7DLVKǀQREX御即位大甞祭大典図案 大正之部, E\6KLPRPXUD7DPDKLUR 下村玉廣. 8QVǀGǀ © 2019 by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Please note that the contents of Japan Review may not be used or reproduced without the written permis- sion of the Editor, except for short quotations in scholarly publications in which quoted material is duly attributed to the author(s) and Japan Review. Japan Review Number 34, December 2019 Published by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies 3-2 Goryo Oeyama-cho, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto 610-1192, Japan Tel. 075-335-2210 Fax 075-335-2043 Print edition: ISSN 0915-0986 Online edition: ISSN 2434-3129 japan review Journal of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Number 34 2019 About the Journal Japan Review is a refereed journal published annually by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies since 1990. -

Diss Master Draft-Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Visual and Material Culture at Hokyoji Imperial Convent: The Significance of "Women's Art" in Early Modern Japan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fq6n1qb Author Yamamoto, Sharon Mitsuko Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan.