Sowon S. Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

KOREA's LITERARY TRADITION 27 Like Much Folk and Oral Literature, Mask Dances Ch'unhyang Chòn (Tale of Ch'unhyang)

Korea’s Literary Tradition Bruce Fulton Introduction monks and the Shilla warrior youth known as hwarang. Corresponding to Chinese Tang poetry Korean literature reflects Korean culture, itself and Sanskrit poetry, they have both religious and a blend of a native tradition originating in Siberia; folk overtones. The majority are Buddhist in spirit Confucianism and a writing system borrowed from and content. At least three of the twenty-five sur- China; and Buddhism, imported from India by way viving hyangga date from the Three Kingdoms peri- of China. Modern literature, dating from the early od (57 B.C. – A.D. 667); the earliest, "Sòdong yo," 1900s, was initially influenced by Western models, was written during the reign of Shilla king especially realism in fiction and imagism and sym- Chinp'yòng (579-632). Hyangga were transcribed in bolism in poetry, introduced to Korea by way of hyangch'al, a writing system that used certain Japan. For most of its history Korean literature has Chinese ideographs because their pronunciation embodied two distinct characteristics: an emotional was similar to Korean pronunciation, and other exuberance deriving from the native tradition and ideographs for their meaning. intellectual rigor originating in Confucian tradition. The hyangga form continued to develop during Korean literature consists of oral literature; the Unified Shilla kingdom (667-935). One of the literature written in Chinese ideographs (han- best-known examples, "Ch'òyong ka" (879; “Song of mun), from Unified Shilla to the early twentieth Ch'òyong”), is a shaman chant, reflecting the influ- century, or in any of several hybrid systems ence of shamanism in Korean oral tradition and sug- employing Chinese; and, after 1446, literature gesting that hyangga represent a development of written in the Korean script (han’gùl). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

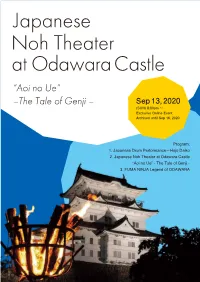

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Colonial Echo, 1937

The Colonial Echo 1937 • ROGER B. CHILD • EDITOR • • FRANCIS REN DEDICATION • This 1937 Colonial Echo is dedicated to J. Wilfred Lambert who, as Dean of Freshmen, has performed his office with pa- tience and understanding, and who offers to each entering student an intelligent guidance, a helpful friendliness and a vital idealism born of his own deep- rooted faith in the College of William and Mary. DEAN J. WILFRED LAMBERT Views of the College The Board of Visitors The Officers of Administration The Officers of Instruction DE COLLEGIO Haec libelli pars, quae ad res Collegii ipsius atque eius curatores praeceptores- que pertmet, summo konorum cursus aiscrimine servato, multo tamen plus quam seriem graauum munerumque acadenncorum indicat. Proponit enim eos qui res maximas gesserunt litterarias et qui nunciam luvenes mstituunt m d-octrmas plurimas, quarum quidem ratio deliberandi libera fecundaque non est ininiina. THE COLLEGE OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY It Is always difficult to obtain views of the college that are new and different from those that have been used before. But in this section of the book, an attempt has been made to choose the pictures in the interests of good scenic representation, and best possible compo- sition, though restricted to so few of the build- ings for subject matter. THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE The President's house was built in 1732 and has been the home of the successive presidents of the college. This house is a fine example of eighteenth century Virginian Architecture, and was restored in 193! by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. THE WREN COURTYARD attrac- The Wren Courtyard is one of the most tive spots In the college, and gives a pronounced are Old World impression. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

The Reflection of the Concept of Marriage of Heian Japanese Aristocracy Revealed in Murasaki Shikibu's

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI v PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Yunita Prabandari Nomor Mahasiswa : 084214081 Demi pengembangan ilmu -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2019)

The Triple Crown (1867-2019) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug O’Neill Keith Desormeaux Steve Asmussen Big Chief Racing, Head of Plains Partners, Rocker O Ranch, Keith Desormeaux Reddam Racing LLC (J. Paul Reddam) WinStar Farm LLC & Bobby Flay 2015 American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah American Pharoah Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza American Pharoah Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) Zayat Stables LLC (Ahmed Zayat) 2014 California Chrome California Chrome Tonalist California Chrome Victor Espinoza Victor Espinoza Joel Rosario California Chrome Art Sherman Art Sherman Christophe Clement Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Steve Coburn & Perry Martin Robert S. -

The Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Tale of Genji and a Dream of Red Mansions

Volume 5, No. 2-3 24 The Cross-cultural Comparison of The Tale of Genji and A Dream of Red Mansions Mengmeng ZHOU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China; Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Tale of Genji, and A Dream of Red Mansions are the classic work of oriental literature. The protagonists Murasaki-no-ue and Daiyu, as the representatives of eastern ideal female images, reflect the similarities and differences between Japanese culture and Chinese culture. It is worthwhile to elaborate and analyze from cross-cultural perspective in four aspects: a) the background of composition; b)the psychological character; c) the cultural aesthetic orientation; and d)value orientation. Key Words: Murasaki-no-ue; Daiyu; cross-cultural study 1. THE BACKGROUND OF COMPOSITION The Tale of Genji, is considered to be finished in its present form between about 1000 and 1008 in Heian-era of Japan. The exact time of final copy is still on doubt. The author Murasaki Shikibu was born in a family of minor nobility and a member the northern branch of the Fujiwara clan. It is argued that her given name might have been Fujiwara Takako. She had been a maid of honor in imperial court. As a custom in imperial court, the maid of honor was given an honorific title by her father or her brother‘s position. ―Shikibu‖ refers to her elder brother‘s position in the Bureau of Ceremony (shikibu-shō).―Murasaki‖ is her nickname, which is called by the readers, after the character Murasaki-no-ue in The Tale of Genji. -

The Triple Crown (1867-2020)

The Triple Crown (1867-2020) Kentucky Derby Winner Preakness Stakes Winner Belmont Stakes Winner Horse of the Year Jockey Jockey Jockey Champion 3yo Trainer Trainer Trainer Year Owner Owner Owner 2020 Authentic (Sept. 5, 2020) f-Swiss Skydiver (Oct. 3, 2020) Tiz the Law (June 20, 2020) Authentic John Velazquez Robby Albarado Manny Franco Authentic Bob Baffert Kenny McPeek Barclay Tagg Spendthrift Farm, MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Stables & Starlight Racing Peter J. Callaghan Sackatoga Stable 2019 Country House War of Will Sir Winston Bricks and Mortar Flavien Prat Tyler Gaffalione Joel Rosario Maximum Security Bill Mott Mark Casse Mark Casse Mrs. J.V. Shields Jr., E.J.M. McFadden Jr. & LNJ Foxwoods Gary Barber Tracy Farmer 2018 Justify Justify Justify Justify Mike Smith Mike Smith Mike Smith Justify Bob Baffert Bob Baffert Bob Baffert WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC WinStar Farm LLC, China Horse Club, Starlight Racing & Head of Plains Partners LLC 2017 Always Dreaming Cloud Computing Tapwrit Gun Runner John Velazquez Javier Castellano Joel Ortiz West Coast Todd Pletcher Chad Brown Todd Pletcher MeB Racing, Brooklyn Boyz, Teresa Viola, St. Elias, Siena Farm & West Point Thoroughbreds Bridlewood Farm, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners & Robert V. LaPenta Klaravich Stables Inc. & William H. Lawrence 2016 Nyquist Exaggerator Creator California Chrome Mario Gutierrez Kent Desormeaux Irad Ortiz Jr. Arrogate Doug