The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Literature: a Spring Rain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations 1

Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations 1 Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations Chair • Whitney Cox Professors • Muzaffar Alam - Director of Graduate Studies • Dipesh Chakrabarty • Ulrike Stark • Gary Tubb Associate Professors • Whitney Cox • Thibaut d’Hubert • Sascha Ebeling • Rochona Majumdar Assistant Professors • Andrew Ollett • Tyler Williams - Director of Undergraduate Studies Visiting Professors • E. Annamalai Associated Faculty • Daniel A. Arnold (Divinity School) • Christian K. Wedemeyer (Divinity School) Instructional Professors • Mandira Bhaduri • Jason Grunebaum • Sujata Mahajan • Timsal Masud • Karma T. Ngodup Emeritus Faculty • Wendy Doniger • Ronald B. Inden • Colin P. Masica • C. M. Naim • Clinton B.Seely • Norman H. Zide The Department The Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations is a multidisciplinary department comprised of faculty with expertise in the languages, literatures, histories, philosophies, and religions of South Asia. The examination of South Asian texts, broadly defined, is the guiding principle of our Ph.D. degree, and the dissertation itself. This involves acquaintance with a wide range of South Asian texts and their historical contexts, and theoretical reflection on the conditions of understanding and interpreting these texts. These goals are met through departmental seminars and advanced language courses, which lead up to the dissertation project. The Department admits applications only for the Ph.D. degree, although graduate students in the doctoral program may receive an M.A. degree in the course of their work toward the Ph.D. Students admitted to the doctoral program are awarded a six-year fellowship package that includes full tuition, academic year stipends, stipends for some summers, and medical insurance. Experience in teaching positions is a required part of the 2 Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations program, and students are given opportunities to teach at several levels in both language courses and other courses. -

547-553 Poetry China Song and After.Indd

Poetry: China (Song and After) Chinese Buddhist poetry from the Song (宋; 960– Chan Buddhist Poetry in the Song and 1279) onward was marked by the dominance of Its Influence Chan Buddhism and the participation of a newly emergent literary elite whose writings were increas- The growth and institutionalization of Chan ingly published and preserved due to advances in Buddhism as the foremost Buddhist tradition of printing technology. All of these factors, their indi- the Song, along with the invention of new forms of vidual development and occasional confluence, are Chan literature, had an enormous impact on the the most salient traits of Chinese Buddhist literature collection and conceptualization of poetry writ- from the Song until the literary May Fourth Move- ten by Buddhist monks. The two most prominent, ment (1919). and closely related, Chan literary innovations, The special relationship between Buddhism and “lamp records” (denglu [燈錄]) and “recorded say- poetry has been a recurring subject of scholarship, ings” (yulu [語錄]), both came to maturity during mostly focused on Chan (Demiéville, 1970; Iriya, the Song. While denglu are extensive genealogical 1983; Ge, 1986; Watson, 1988), which has further histories of Chan lineages that compile exemplary yielded the study of Chan poetry and aesthetics (Pi, writings and anecdotes from hundreds of masters, 1995; Zhang, 2006). The study of Buddhist poetry yulu collect the sermons and writings of individual as literary history has focused on noteworthy Bud- abbots. Both types of literature include the poetry of dhist poet-monks and established poets who wrote Chan monks in significant quantities, which tends Buddhist-themed poetry (Sun, 2006; Xiao, 2012). -

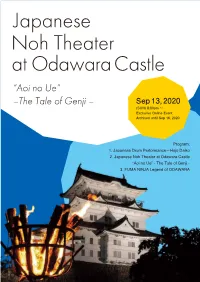

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Stephen Carl Berkwitz

STEPHEN CARL BERKWITZ Department of Religious Studies Missouri State University 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897 (417) 836-4147 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://missouristate.academia.edu/StephenBerkwitz EDUCATION Ph.D. 1999 University of California, Santa Barbara (Religious Studies) Dissertation: “The Ethics of Buddhist History: A Study of the Pāli and Sinhala Thūpavaṃsas.” Advisors: Ninian Smart (Chair), Gerald J. Larson, Barbara Holdrege, and Charles Hallisey M.A. 1994 University of California, Santa Barbara (Religious Studies) Thesis: “Reforming Tradition and Forming Identity in Twentieth-Century Sri Lankan Buddhism.” B.A. 1991 University of Vermont (Religion) EMPLOYMENT AND COURSES TAUGHT Head, Department of Religious Studies, Missouri State University, Fall 2012-present Professor, Department of Religious Studies, Missouri State University, Paths of World Religions, Buddhism, Religions of China and Japan, Yoga and Meditation, Theories of Religion, Sex, Power and Devotion in South Asian Poetry (graduate), Religion, Colonialism, Postcolonialism (graduate), Tantra: Body and Power in South Asia (graduate), Fall 2010-present Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies. Missouri State University, Paths of World Religions, Buddhism, Religion: Colonialism/Postcolonialism, Theories of Religion, History of Indian Buddhism (graduate), Buddhism in the Modern World. Pali, Sanskrit, Religions of China and Japan, Fall 2004-Spring 2010 Visiting Instructor, Missouri-London Study Abroad Program, International -

How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China

how poetry became meditation Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.2: 113-151 thomas j. mazanec How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China abstract: In late-ninth-century China, poetry and meditation became equated — not just meta- phorically, but as two equally valid means of achieving stillness and insight. This article discusses how several strands in literary and Buddhist discourses fed into an assertion about such a unity by the poet-monk Qiji 齊己 (864–937?). One strand was the aesthetic of kuyin 苦吟 (“bitter intoning”), which involved intense devotion to poetry to the point of suffering. At stake too was the poet as “fashioner” — one who helps make and shape a microcosm that mirrors the impersonal natural forces of the macrocosm. Jia Dao 賈島 (779–843) was crucial in popularizing this sense of kuyin. Concurrently, an older layer of the literary-theoretical tradition, which saw the poet’s spirit as roaming the cosmos, was also given new life in late Tang and mixed with kuyin and Buddhist meditation. This led to the assertion that poetry and meditation were two gates to the same goal, with Qiji and others turning poetry writing into the pursuit of enlightenment. keywords: Buddhism, meditation, poetry, Tang dynasty ometime in the early-tenth century, not long after the great Tang S dynasty 唐 (618–907) collapsed and the land fell under the control of regional strongmen, a Buddhist monk named Qichan 棲蟾 wrote a poem to another monk. The first line reads: “Poetry is meditation for Confucians 詩為儒者禪.”1 The line makes a curious claim: the practice Thomas Mazanec, Dept. -

The Reflection of the Concept of Marriage of Heian Japanese Aristocracy Revealed in Murasaki Shikibu's

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI THE REFLECTION OF THE CONCEPT OF MARRIAGE OF HEIAN JAPANESE ARISTOCRACY REVEALED IN MURASAKI SHIKIBU’S THE TALE OF GENJI AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By YUNITA PRABANDARI Student Number: 084214081 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2015 ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI v PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Yunita Prabandari Nomor Mahasiswa : 084214081 Demi pengembangan ilmu -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

Developments in Buddhist Studies, 2015

Canadian Journal of Buddhist Studies ISSN 1710-8268 http://journals.sfu.ca/cjbs/index.php/cjbs/index Number 11, 2016 Developments in Buddhist Studies, 2015 A Report on the Symposium “Buddhist Studies Today” University of British Columbia, Vancouver July 7-9, 2015 Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Arthur E. Link Distinguished University Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies University of Michigan Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. Developments in Buddhist Studies, 2015 A Report on the Symposium “Buddhist Studies Today” University of British Columbia, Vancouver July 7-9, 2015 Donald S. Lopez Jr. UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Abstract This report summarizes the proceedings of “Buddhist Studies Today,” a symposium convened at the University of British Columbia and sponsored by the American Coun- cil of Learned Societies with support from The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation. It was a three-day symposium to celebrate the first Dissertation Fellows of The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Program in Buddhist Studies and to reflect on their work. 6 Lopez, Buddhist Studies Today Introduction The context On January 1, 1966, a meeting was held at the University of British Co- lumbia to assess the state of the field of Buddhist Studies and to establish an organization to support its scholarship. A report of the meeting by Holmes Welch, titled “Developments in Buddhist Studies,” was published in the May 1996 issue of the now defunct Newsletter (XVII.5, 12-16) of the American Council of Learned Societies. -

The Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Tale of Genji and a Dream of Red Mansions

Volume 5, No. 2-3 24 The Cross-cultural Comparison of The Tale of Genji and A Dream of Red Mansions Mengmeng ZHOU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China; Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Tale of Genji, and A Dream of Red Mansions are the classic work of oriental literature. The protagonists Murasaki-no-ue and Daiyu, as the representatives of eastern ideal female images, reflect the similarities and differences between Japanese culture and Chinese culture. It is worthwhile to elaborate and analyze from cross-cultural perspective in four aspects: a) the background of composition; b)the psychological character; c) the cultural aesthetic orientation; and d)value orientation. Key Words: Murasaki-no-ue; Daiyu; cross-cultural study 1. THE BACKGROUND OF COMPOSITION The Tale of Genji, is considered to be finished in its present form between about 1000 and 1008 in Heian-era of Japan. The exact time of final copy is still on doubt. The author Murasaki Shikibu was born in a family of minor nobility and a member the northern branch of the Fujiwara clan. It is argued that her given name might have been Fujiwara Takako. She had been a maid of honor in imperial court. As a custom in imperial court, the maid of honor was given an honorific title by her father or her brother‘s position. ―Shikibu‖ refers to her elder brother‘s position in the Bureau of Ceremony (shikibu-shō).―Murasaki‖ is her nickname, which is called by the readers, after the character Murasaki-no-ue in The Tale of Genji.