Of National Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Members

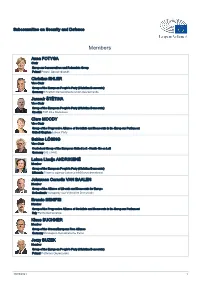

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

BIGGEST INEQUALITY SURGE SINCE 1980S

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 433 22 March 2017 50p/£1 Inside: BIGGEST INEQUALITY Keep the guard on the SURGE SINCE 1980s train! Strikes against driver-only operation spread. See page 10 Greece: a fourth memorandum? Theodora Polenta discusses the current political situation in Greece. See pages 6-7 The art of Buffy “If nothing is done to change [the] outlook, the current parlia - ment [2015-20] will go down as being the worst on record for in - come growth in the bottom half of the income distribution. “It will also represent the biggest rise in inequality since the end of the 1980s”. More page 5 On the 20th anniversary of the TV RICH AND series, Carrie Evans discusses its impact. See page 9 Join Labour! POOR: THE Grassroots Momentum: an opportunity almost missed GAP WIDENS See page 4 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org G20 deletion signals danger By Rhodri Evans From revolutionary to bourgeois minister When 20 governments met for the G20 summit in late 2008, at the worst of the global credit crash, their agreed joint state - Martin McGuinness ment included just one hard commitment: to resist protec - tionism, to avoid new trade By Gerry Bates minister, and made a series of real barriers. and symbolic concessions to union - Not perfectly, but on the whole, ism — signing up to support Police Martin McGuinness became a that commitment held, and Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), helped the slump level out in late revolutionary, by his own lights, and shaking the Queen’s hand in as a teenager, and ended his life 2009 rather than continuing June 2012, which he described as downwards for three or four as a bourgeois minister in a po - “in a symbolic way offering the litical system he had vowed to years as in the 1930s, when states hand of friendship to unionists”. -

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study Release Notes Sebastian Adrian Popa Hermann Schmitt Sara B Hobolt Eftichia Teperoglou Original release 1 January 2015 MZES, University of Mannheim Acknowledgement of the data Users of the data are kindly asked to acknowledge use of the data by always citing both the data and the accompanying release document. How to cite this data: Schmitt, Hermann; Popa, Sebastian A.; Hobolt, Sara B.; Teperoglou, Eftichia (2015): European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5160 Data file Version 2.0.0, doi:10.4232/1. 12300 and Schmitt H, Hobolt SB and Popa SA (2015) Does personalization increase turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, Online first available for download from: http://eup.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/06/03/1465116515584626.full How to cite this document: Sebastian Adrian Popa, Hermann Schmitt, Sara B. Hobolt, and Eftichia Teperoglou (2015) EES 2014 Voter Study Advance Release Notes. Mannheim: MZES, University of Mannheim. Acknowledgement of assistance The 2014 EES voter study was funded by a consortium of private foundations under the leadership of Volkswagen Foundation (the other partners are: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Stiftung Mercator, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian). It profited enormously from to synergies that emerged from the co-operation with the post-election survey funded by the European Parliament. Last but certainly not least, it benefited from the generous support of TNS Opinion who did the fieldwork in all the 28 member countries . The study would not have been possible the help of many colleagues, both members of the EES team and country experts form the wider academic community, who spent valuable time on the questionnaire and study preparation, often at very short notice. -

Reshaping Politics of the Left and Centre in Greece After the 2014 EP Election Filippa Chatzistavrou and Sofia Michalaki

Commentary No. 21/ 10 September 2014 Reshaping politics of the left and centre in Greece after the 2014 EP election Filippa Chatzistavrou and Sofia Michalaki he European Parliament elections in Greece earlier this year highlighted a conundrum: that of minority political parties struggling to mobilise voters in the event of snap national elections in T spring 2015. The political landscape is confused and volatile; the right and extreme-right on the political spectrum are accorded a disproportionately large place in political debate, while ideological positioning by the centre and centre-left does not seem to be a major concern for political analysts. The radical left-wing SYRIZA party is attempting to maintain a ‘leftist’ profile while demonstrating its capacity to govern through a strategy of image normalisation. SYRIZA faces a profound challenge in defining a modern political programme in which policy-specific party positions will be clearly identified, and in which political engagement can be matched with concrete political proposals. This conundrum looks even more insoluble in the face of internal criticism about attempts by the party leadership to broaden its electoral base to be more inclusive. Electoral winners and political losers from across the spectrum Official electoral results showed SYRIZA to be the winner of the 2014 EP election. But if we look more closely at the results and compare them to those of the last national elections (2012), we see that despite a spectacular launch in 2012, SYRIZA recorded a loss of more than 100,000 votes in the EP election. This loss could partly be attributed to poor voter turnout, although traditionally in Greece the opposition significantly increases its vote share in EP elections. -

A Weightless Hegemony

susan watkins Editorial A WEIGHTLESS HEGEMONY New Labour’s Role in the Neoliberal Order he Centre Left governments that dominated the North Atlantic zone up to the turn of the millennium have now all Tbut disappeared. Within six months of Bush’s victory in the United States, the Olive Tree coalition had crumbled before Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. The autumn of 2001 saw Social Democrats driven from office in Norway and Denmark. In April 2002 Kok’s Labour-led government resigned over a report pointing to Dutch troops’ complicity in the Srebrenica massacre. The following month, Jospin came in a humiliating third behind Chirac and Le Pen in the French presidential contest, and the Right triumphed in the legislative elections. In Germany, the spd–Green coalition clung on by a whisker, aided by providential floods. Though the sap retains its historic grip on Sweden it now lacks an absolute majority, and Persson was trounced in the 2003 campaign for euro entry. In Greece, where pasok has only been out of power for three years since 1981, Simitis squeaked back in 2000 with a 43.8 to 42.7 per cent lead. Within this landscape, Britain has been the conspicuous exception. In the United Kingdom alone a Centre Left government remains firmly in place, its grip on power strengthened, if anything, in its second term of office, and still enjoying a wide margin of electoral advantage. Both features—New Labour’s survival against the general turn of the polit- ical wheel, and the scale of its domestic predominance—set it apart within the oecd zone. -

EU Agricultural Policy Analysis1 Policies Specific to Greece Since the Mid 20Th Century

EUROMED SUSTAINABLE CONNECTIONS ANNA LINDH FOUNDATION POLICY ANALYSIS 1:1. THE HISTORY OF OLIVE OIL February 20, 2008 THE HISTORY OF OLIVE OIL1 The Cretan word for olive, elaiwa, also changed as the olive and its oil moved north and west through Southern Europe, becoming “The whole Mediterranean, the sculpture, the palm, the gold elaia in Classical Greek, oliva in Latin, olivera in Spanish, olew in beads, the bearded heroes, the wine, the ideas, the shops, the Welsh and olive in German. There is speculation that the Greek moonlight, the winged gorgons, the bronze men, the word for olive tree, elaion, may have been derived from the philosophers,- all of it seems to rise in the sour, pungent taste of Semitic Phoenician word, el’you, meaning superior, perhaps these black olives between the teeth. A taste older than meat, alluding to the higher quality associated with olive oil compared to older than wine. A taste as old as cold water. Only the sea itself other oils that were available at the time. seems as ancient a part of the region as the olive and its oil, that like no other products of Nature, have shaped civilizations from Just as with the word zeit, many name places throughout the remotest antiquity to the present.” Mediterranean region relate to the Greek word, elaia and the Latin Laurence Durrell, Prospero’s Cell, 1945 word, oliva: Ela, a cape and river in Cyprus; Elaia, Elaikhorian, Elaiofiton, Elaion, Elaiotopos, all villages in Greece; the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem; Olivet, a village in France: and Olivares, a Spanish village. -

First Thoughts on the 18 & 25 May 2014 Elections in Greece

GREEK ELECTIONS 2014 First thoughts on the 18 & 25 May 2014 elections in Greece Andronidis |Bertsou| Boussalis |Chadjipadelis| Drakaki |Exa daktylos|Halikiopoulou| Kamekis |Karakasis| Katsaitis |Kats ambekis| Kulich |Kyris |Lefkofridi| Leontitsis |Manoli|Margarit is| Nevradakis |Papazoglou| Prodromidou |Rapidis| Sigalas | Sotiropoulos |Theologou| Tsarouhas |Tzagkarakis |Vamvak as| Vasilopoulou |Xypolia|Andronidis|Bertsou|Boussalis|C hadjipadelis|Drakaki|Exadaktylos| Halikiopoulou |Kamekis| Karakasis |Katsaitis| Katsambekis |Kulich|Kyris| Lefkofridi |L eontitsis| Manoli |Margaritis |Nevradakis| Papazoglou |Prodr omidou| Rapidis |Sigalas|Sotiropoulos| Theologou |Tsarouh as|Tzagkarakis| Vamvakas |Vasilopoulou| Xypolia |Androni dis| Bertsou |Boussalis| Chadjipadelis |Drakaki| Exadaktylos Edited by Roman Gerodimos www.gpsg.org.uk GPSG PAMPHLET #3 First thoughts on the 18 & 25 May 2014 elections in Greece Editorial | Domestic Message in a European Bottle A friend recently noted that the European Parliament election is like Eurovision: “nobody remembers it the next day, but still, everybody talks about it and bets on it beforehand”. This rule may be about to be broken in Greece: this particular EP election not only coincided with two rounds of local (municipal and regional) elections – therefore creating a cumulative political event – but it was also the first national contest since the historic elections of May and June 2012, which marked the breakdown of the post-1974 party system. The recent elections were important for other reasons, too: -

Should Access to Money Laundering Information for Tax Authorities Be Facilitated?

Should access to money laundering information for tax authorities be facilitated? The vote of the MEPs Within the broader EU agenda on the measures to fight tax avoidance and tax evasion, the EP approved a proposal on facilitating the access to money laundering information for tax authorities. In fact, the fight against money laundering and the one against tax evasion are often intertwined. This initiative, also because of its specific and technical scope, was well received by the MEPs who widely approved the proposal. Even though there were some disagreements coming from some national delegations such as the British and the Polish ones, a large majority of MEPs supported the text (86%). In fact, apart from EFDD and ECR, the majority of MEPs from all other political groups voted in favor. Greek MEPs were on the same line with the majority of the EU Parliament in regard to access to ant-money laundering by tax authorities, as they all voted in favour with some exceptions. In fact, the members of the Communist Party DISTRIBUTION OF GREEK POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT IN 2016 of Greece, Konstantinos Papadokis and Non- Satirias Zarioanopoulis as well as Inscrits: European KKE, Golden United Left- Kostantinka Kuneva (Syriza) decided to Dawn Nordic abstain (the latter did not vote in the plenary, Green Left: European SYRIZA but she notified her intention to abstain Conservativ eventually). Additionally, Eva Kaili (PASOK) es and Reformists: did not vote. ANEL Progressive Alliance of Socialists European People's and Party: Democrats: -

Electoral Lists Ahead of the Elections to the European Parliament from a Gender Perspective ______Details)

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs ____________________________________________________________________________________________ EL GREECE This case study presents the situation in Greece as regards the representation of men and women on the electoral lists in the elections for the European Parliament 2014. The first two tables indicate the legal situation regarding the representation of men and women on the lists and the names of all parties and independent candidates which will partake in these elections. The subsequent tables are sorted by those political parties which were already represented in the European Parliament between 2009 and 2014 and will firstly indicate whether and how a party quota applies and then present the first half of the candidates on the lists for the 2014 elections. The legal situation in Greece regarding the application of gender quotas 2009-2013: 2262 Number of seats in the EP 2013-2014: 21 System type: Preferential Voting Threshold: Seats are allocated among all the lists of parties or coalitions of parties who obtain the 3% of the votes. The votes of Greeks living in other EU Member States are also counted. Number of constituencies: Single electoral constituency Compulsory voting: Yes. The obligation to vote in all Electoral System type for levels of elections is defined by in the Constitution the EP election 2014 (Art.51 par.3) and the Electoral Code. Legal Sources: Act concerning the election of the representatives of the Assembly by direct universal suffrage, Official Journal L 278, 08/10/1976 P. 0005 – 0011. Constitution of 1976 Law for European Elections No. 4255/2014 National gender quotas YES, Legislated Candidate Quotas apply, introduced with Law apply: Yes/No 4255/2014 (Law for European Elections) , Article 3 par. -

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2019a from August 21, 2019 Manifesto Project Dataset - List of Political Parties Version 2019a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the name of the party or alliance in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In the case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties it comprises. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list. If the composition of an alliance has changed between elections this change is reported as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party has split from another party or a number of parties has merged and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 2 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. Elections -

Release Notes for the Manifesto Project Dataset / MARPOR Full Dataset: Updates (2011-2020B), Changes, Corrections, and Known Errors

Release Notes for the Manifesto Project Dataset / MARPOR Full Dataset: Updates (2011-2020b), changes, corrections, and known errors 1 MARPOR Full Dataset 2020b: December 2020 Version Elections added: • Austria 2019 • Denmark 2019 • Hungary 2018 • Israel 2019 April • Montenegro 2020 • Portugal 2019 • Spain 2019 November • Ukraine 2014 Corrections and changes: • Harmonized the election data of two italian electoral alliances and their members for 2006 election: • Following parties are affected: { House of Freedom (32629) { Green Federation (32110) { Communist Refoundation Party (32212) { Party of Italian Communists (32213) { Rose in the Fist (32221) { Olive Tree (32329) { List Di Pietro - Italy of Values (32902) { Autonomy Liberty Democracy (32903) { South Tyrolean Peoples Party (32904) { Popular Democratic Union for Europe (32953) { The Union Prodi (32955) 2 { Union for Christian and Center Democrats (32530) { Go Italy (32610) { New Italian Socialist Party (32611) { National Alliance (32710) { Northern League (32720) { Italy in the World (32952) • We changed a party family coding: { The Union - Prodi (32955) to 98 (diverse/alliance) • We corrected the coding of a few quasi-sentences in three documents which results in minor changes to their per-variables. The following manifesto are affected: (party date) { Lithuania: 88320 200810 { Slovakia: 96521 200606, 96710 200606 • We corrected a counting mistake of the codes of one document, resulting in changes of the per-values. { Slovakia: 96423 201603 • Dropped data for one observations: { Polish -

Broad Parties and Anti-Austerity Governments: from Defeat to Defeat, Learning the Lessons of Syriza’S Debacle

Débats Tendance CLAIRE du NPA http://www.tendanceclaire.org Broad parties and anti-austerity governments: from defeat to defeat, learning the lessons of Syriza’s debacle Versão em português | Version en français The NPA leadership, the majority of which is organically linked to the majority of the International committee of the Fourth international (ICFI), refuses to draw all the lessons from a way of building organizations that has continuously failed and led to political and organizational catastrophes in its national sections, with of course a very negative overall impact, for more than twenty years. The question is: what policy of the ICFI leadership is at the heart of such major and repeated failures, of utter disasters, even, in certain countries? After compiling a non-exhaustive list of the most significant among the regrettable and disastrous experiences of the past two decades, this contribution focuses on the latest tragedy to date: Greece. The heart of the political problem first appears in the more or less empirical choices of the ICFI in the 1980s, then becomes systematic in the 1990s after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and its easy colonization by capital. The political bankruptcy of the Socialist Democracy current (DS) in Brazil In 1979-80, we first see the small Brazilian section of the ICFI participate in the construction of the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT). Participating in building a mass party is not a problem per se: it is - or rather, it should be - a tactical choice, all the more necessary in a context where all organizations either of the non-Stalinist left or breaking with Stalinism were then to be found in the PT.