First Thoughts on the 18 & 25 May 2014 Elections in Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of Syriza: an Interview with Aristides Baltas

THE RISE OF SYRIZA: AN INTERVIEW WITH ARISTIDES BALTAS This interview with Aristides Baltas, the eminent Greek philosopher who was one of the founders of Syriza and is currently a coordinator of its policy planning committee, was conducted by Leo Panitch with the help of Michalis Spourdalakis in Athens on 29 May 2012, three weeks after Syriza came a close second in the first Greek election of 6 May, and just three days before the party’s platform was to be revealed for the second election of 17 June. Leo Panitch (LP): Can we begin with the question of what is distinctive about Syriza in terms of socialist strategy today? Aristides Baltas (AB): I think that independently of everything else, what’s happening in Greece does have a bearing on socialist strategy, which is not possible to discuss during the electoral campaign, but which will present issues that we’re going to face after the elections, no matter how the elections turn out. We haven’t had the opportunity to discuss this, because we are doing so many diverse things that we look like a chicken running around with its head cut off. But this is precisely why I first want to step back to 2008, when through an interesting procedure, Synaspismos, the main party in the Syriza coalition, formulated the main elements of the programme in a book of over 300 pages. The polls were showing that Syriza was growing in popularity (indeed we reached over 15 per cent in voting intentions that year), and there was a big pressure on us at that time, as we kept hearing: ‘you don’t have a programme; we don’t know who you are; we don’t know what you’re saying’. -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTION IN GREECE 7th July 2019 European New Democracy is the favourite in the Elections monitor Greek general election of 7th July Corinne Deloy On 26th May, just a few hours after the announcement of the results of the European, regional and local elections held in Greece, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA), whose party came second to the main opposition party, New Analysis Democracy (ND), declared: “I cannot ignore this result. It is for the people to decide and I am therefore going to request the organisation of an early general election”. Organisation of an early general election (3 months’ early) surprised some observers of Greek political life who thought that the head of government would call on compatriots to vote as late as possible to allow the country’s position to improve as much as possible. New Democracy won in the European elections with 33.12% of the vote, ahead of SYRIZA, with 23.76%. The Movement for Change (Kinima allagis, KINAL), the left-wing opposition party which includes the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), the Social Democrats Movement (KIDISO), the River (To Potami) and the Democratic Left (DIMAR), collected 7.72% of the vote and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), 5.35%. Alexis Tsipras had made these elections a referendum Costas Bakoyannis (ND), the new mayor of Athens, on the action of his government. “We are not voting belongs to a political dynasty: he is the son of Dora for a new government, but it is clear that this vote is Bakoyannis, former Minister of Culture (1992-1993) not without consequence. -

Greece Political Briefing: an Assessment of SYRIZA's Review

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 26, No. 1 (GR) Febr 2020 Greece political briefing: An assessment of SYRIZA’s review George N. Tzogopoulos 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 An assessment of SYRIZA’s review In February 2020 the central committee of SYRIZA approved the party’s review covering the period from January 2015 until July 2019. While the performance of SYRIZA after the summer of 2015 was largely based on bailout obligations and was efficient, its stance in the first semester of that year stigmatized not only the national economy but also the party itself. The review discusses successes and failures and constitutes a useful document in the effort of the main opposition party to learn by its mistakes and develop attractive governmental proposals. A few months after the general election of July 2019, the main opposition SYRIZA party is keeping a low profile in domestic politics. Its electoral defeat has required a period of self- criticism and internal debate in order for the party to gradually start formulating new policies which will perhaps allow it to win the next national election. Against this backdrop, three experienced politicians, former vice-President of the government Yiannis Dragasakis, former Shipping Minister Theodoros Dritsas and former Education Minister Aristides Baltas prepared a review of the party’s 4.5 administration year. The review was presented to SYRIZA’s central committee at the beginning of February 2020 and was subsequently approved. -

Greece Wave 3

GREECE WAVE 3 Pre-election Study June 2019 Marina Costa Lobo Efstratios-Ioannis Kartalis Nelson Santos Roberto Pannico Tiago Silva Table of Contents 1. Technical Report 2. Report Highlights 3. Most important Problem Facing Greece 4. Ideological Placement of Main Parties 5. Party identification 6. National Issues: Evaluation of the Economy 7. National Issues: Evaluation of the Current Syriza Government 8. National Issues: Economic situation 9. National Issues: Immigration 10. National Issues: PRESPA Agreement 11. Greece and the EU: Membership 12. Greece and the EU: Benefits of Membership 13. Greece and the EU: Political Integration? 14. Greece and the EU: Benefits of the Euro 15. Greece and the EU: Exit from the Euro 1. Technical Report This study is part of the MAPLE Project, ERC – European Research Council Grant, 682125, which aims to study the Politicisation of the EU before and after the Eurozone Crisis in Belgium, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain. In each of these countries an online panel will be carried out just before and just after the legislative elections. This report pertains to the pre-election panel of Greece legislative elections 2019 to be held on 7 July. Our questionnaire seeks to model the political context of political choices, and to understand the importance which European attitudes may have in voting behaviour. In Greece, we have partnered with Metron Analysis. We present in this report a number of political attitudes according to stated partisanship in Greece. We are interested in the way in which partisan preferences are related to political attitudes, including national issues as well as those pertaining to the EU. -

Greece and the Case of the 2012

! ! ! ! ! ! "#$$%$!&'(!)*$!+&,$!-.!)*$!/01/!23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!74$%)6-',! ! ! 84$)*&!9&,,64&:6,! ! ! 8!;$'6-#!<-'-#,!=*$,6,!;>?@6))$(!)-!! )*$!A$3&#)@$')!-.!B-46)6%&4!;%6$'%$C!! D'6E$#,6)F!-.!+&46.-#'6&C!;&'!A6$G-! 83#64!1,)C!/01H! ! ! /! =&?4$!-.!+-')$'),! +*&3)$#!1! 8'!I')#-(>%)6-'!)-!)*$!;6G'6.6%&'%$!-.!74$%)-#&4!;F,)$@,JJJJJJJJJJ!K! !+$')#&4!B>LL4$!-.!)*$!"#$$:!+&,$JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMJMMN! =*$!"#$$:!74$%)-#&4!;F,)$@JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMMJJJM10! =*$!O&#$!233-#)>'6)F!-.!)*$!/01/!"#$$:!74$%)6-',JJJJJJJJJJJJJM1P! +*&3)$#!/! 74$%)-#&4!=*$-#F!-.!23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!;F,)$@,JJJJJJJJJJJJJM/0! 23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!74$%)-#&4!=*$-#F!&'(!Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'JJMMJM//! +*&3)$#!H! B&#)F!;)#&)$GF!O$,$&#%*!A$,6G'JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMM/P! Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'!O$,$&#%*!A$,6G'JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMJJH1! +*&3)$#!K! B&#)F!;)#&)$GF!O$,>4),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMJHP! Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'!O$,>4),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMKH! Q$@&4$!+&'(6(&)$!O$,>4),R!S6''6'G!&'(!5-,6'G!B&#)6$,JJJJJJJMJJMMMKT! +*&3)$#!P! +-'%4>,6-',JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMJJJJMMPH! U6?46-G#&3*FJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMN/! 833$'(6VJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJNK! ! H! 56,)!-.!;F@?-4,C!Q6G>#$,C!=&?4$,! ! Q6G>#$!1R!;&@34$!-.!O$4&)6E$!O&':!Q-#@>4&JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMM/W! ! Q6G>#$!/R!;&@34$!A&)&,$)!-.!+&'(6(&)$,!! 7V%*&'G$(!-'!X$Y!A$@-%#&%F!A6,)#6%)!56,),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJM/T! ! Q6G>#$!HR!;&@34$!A&)&,$)!-.!B$#%$')&G$! !! -.!Q$@&4$!+&'(6(&)$,!-'!X$Y!A$@-%#&%F!A6,)#6%)!56,),JJJJJJJJJJMH/! ! Q6G>#$!KR!X&)6-'&4!A&)&,$)!A6,34&F6'G!B$#%$')&G$!-.!+*&'G$! !! -

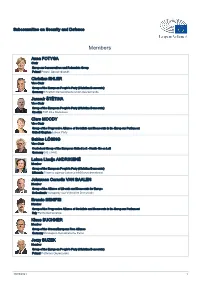

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Kaminis' Lightning Quick NY City Trip Greece Feels the Heat, Moves

S O C V th ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 10 0 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A wEEKLy GREEK-AMERIcAN PUBLIcATION 1915-2015 VOL. 18, ISSUE 916 May 2-8 , 2015 c v $1.50 Kaminis’ Greece Feels t1he Heat, Lightning Moves toward Reforms Quick NY To Unblock Loan Flow City Trip ATHENS – Hopes for a deal on Tsipras said in a television in - Greece’s bailout rose after Prime terview that he expected a deal Minister Alexis Tsipras said he would be reached by May 9, in Mayor of Athens expected an agreement could be time for the next Eurozone reached within two weeks and meeting. Spoke on Gov’t the European Union reported a Greece has to repay the In - pick-up in the negotiations. ternational Monetary Fund a to - At Columbia Univ. Greek stocks rose and its sov - tal of almost 1 billion euros by ereign borrowing rates dropped, May 12. It is expected to have TNH Staff a sign that international in - enough money to make that, if vestors are less worried about it manages to raise as much as NEW YORK – Even during a cri - the country defaulting on its it hopes from a move to grab sis, Greece – and even some of its debts in coming weeks. cash reserves from local entities politicians – can rise to the occa - The European Union said like hospitals and schools. sion and present the world with that Greece’s talks with its cred - But it faces bigger repay - examples of good governance. -

Vigilantism Against Migrants and Minorities; First Edition

11 VIGILANTISM IN GREECE The case of the Golden Dawn Christos Vrakopoulos and Daphne Halikiopoulou Introduction This chapter focuses on vigilantism in Greece. Specifically, it examines the Golden Dawn, a group that beyond engaging in vigilante activities is also the third biggest political party in the country. The Golden Dawn is distinct from a number of other European parties broadly labelled under the ‘far right’ umbrella in that it was formed as a violent grass-roots movement by far-right activists, its main activities prior to 2012 confined to the streets. It can be described as a vigilante group, which frequently uses violence, engages in street politics, has a strong focus on community-based activities, and whose members perceive themselves as ‘street soldiers’. Since 2013 a number of its leading cadres, who are also members of the Greek parliament, have been undergoing trial for maintaining a criminal organization and other criminal acts including murder and grievous bodily harm. The progressive entrenchment of this group in the Greek political system has raised a number of questions about its potential implications on the nature of democracy and policy-making. This chapter examines various dimensions of the Golden Dawn’s vigilante activities. Following a brief overview of the Greek socio- political context, it proceeds to examine the party’s ideology, its organizational structure, its various operations, communications activities and relationships with other political actors and groups in Greece. The political, social and economic environment Political violence and the history of vigilantism in Greece Vigilante and paramilitary activities have a long tradition in Modern Greek history. -

Erika Spyropoulos Honored As Friend of Paideia Archbishop Ieronymos

S O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v A wEEKly GREEK-AmERICAN PUBlICATION www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 16, ISSUE 815 May 25-31, 2013 $1.50 Regeneron’s Success Has Archbishop Ieronymos Welcomed in the U.S. Been Led by the Team of Athens Prelate Went To NYC Cathedral Vangelos & Yancopoulos During Historic Visit TARRYTOWN, N.Y. - The news medical degree. He has made do - that a new asthma drug being de - nations amounting to tens of mil - By Constantine S. Sirigos veloped by Sanofi and Regeneron lions of dollars to those schools. TNH Staff Writer Pharmaceuticals which may help In 1986 he became head of patients whose condition is not Merck & Co. which he led to new NEW YORK – It was a more well controlled by existing medi - heights, and where he gained a emotional Sunday Divine Liturgy cines was also the story of the reputation for being an outstand - than usual at the Archdiocesan partnership of two of the most ing leader. He resigned in 1994 – Cathedral of the Holy Trinity this prominent Greek-American mem - Merck has age limits – and was week, and the yearlong celebra - bers of the pharmaceutical indus - lured to Regeneron by Schleifer tion of the 100th anniversary of try. on the advice of Yancopoulos who the Cathedral of Sts. Constantine Pindar Roy Vagelos, who for - doubted whether his compatriot and Helen in Brooklyn gained its merly headed the giant drug com - would join them. -

Jaharises Host a Very Formidable Greek- American Think Tank

S O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v A wEEkly GrEEk-AmEriCAN PuBliCATiON www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 15, ISSUE 765 June 9-15, 2012 $1.50 Jaharises Host A Very Nightmare Scenario as Crucial Elections Near Formidable Greek- Uncertainty Still Dominates, Along American Think Tank With Pessimism By Constantine S. Sirigos Kondylis, was focused on By Andy Dabilis TNH Staff Writer worldly matters, but in discus - TNH Staff Writer sions among the guests at the NEW YORK – Michael and Mary tables around the room was ATHENS - No money to pay Jaharis hosted a private dinner noted concern about the world salaries, pensions or bills. No for the Founders and guests of in a spiritual dimension. money to import food, fuel or “Faith – An Endowment for Or - Faith’s Spiritual Advisor, Rev. medicine. Paying with IOUs or thodoxy and Hellenism.” The Fr. Alexander Karloutsos, Proto - paper scrips because there’s no event featured presentations presbyter of the Ecumenical Pa - money. A collapse of the banks, four distinguished speakers who triarchate, who was present hospitals unable to care for the connected current events to the with Presbytera Xanthi, has ill, riots in the streets, panic and future of America and the drawn together Greek-Ameri - anarchy. Greek-American community. cans who are leaders across the All those horror stories have Earlier in the day, Faith held spectrum of industry and en - emerged for Greece if the coun - its annual Founders meeting, at deavors to fuel and drive the en - try is forced out of the Eurozone which the year’s priorities were dowment’s work, but the group because parties opposed to the set. -

Golden Dawn and the Right-Wing Extremism in Greece

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Golden Dawn and the Right-Wing Extremism in Greece Lymouris, Nikolaos November 2013 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/106463/ MPRA Paper No. 106463, posted 08 Mar 2021 07:42 UTC Golden Dawn and the Right-Wing Extremism in Greece Dr Nikolaos Lymouris London School of Economics - Introduction There is an ongoing controversy as to whether extreme right has been a longstanding political phenomenon in Greece or whether it is associated with the ongoing economic crisis. The first view suggests that the extreme right ideology has been an integral part of modern Greek political history because of its tradition of far-right dictatorships. The other view emphasizes the fact that the extreme right in Greece never actually existed simply because of the lack of a nationalist middle class. In effect, the emergence of Golden Dawn is simply an epiphenomenon of the economic crisis. At the same time, a broad new trend was adopted not only by the mass media but also -unfortunately– the academia in order to expand – by using false criteria - the political boundaries of the extreme right, to characterize as many parties as possible as extreme right. In any case, the years after the fall of the Greek junta (from 1974 until today) there are mainly two right-wing parties in the Greek political life: the “United Nationalist Movement” (ENEK in its Greek acronym), a fridge organisation acted during the mid 80’s and has ceased to exist, and the Golden Dawn, whose electoral success provoked an important political and social debate. -

The Gatekeeper's Gambit: SYRIZA, Left Populism and the European Migration Crisis

Working Paper The Gatekeeper’s Gambit: SYRIZA, Left Populism and the European Migration Crisis Antonios A. Nestoras Brussels, 02 February 2016 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 Migration and Populism: the New Frontline ................................................ 3 Gateway Greece .............................................................................................. 7 ‘The Biggest Migration Crisis since WWII’ ................................................... 7 Migration Trends and Policies, 2008 - 2014 ................................................. 9 2015: The SYRIZA Pull-Factor? ................................................................... 12 The SYRIZA Gambit ....................................................................................... 15 ‘No Migrant is Illegal’ ................................................................................. 15 ‘It’s all Europe’s Fault’ ................................................................................ 18 ‘Pay or Pray’ ................................................................................................ 21 The EU Reaction ............................................................................................ 24 Hot Spots and Relocation .......................................................................... 24 The Turkish Counter ................................................................................... 25 The Schengen GREXIT