Broad Parties and Anti-Austerity Governments: from Defeat to Defeat, Learning the Lessons of Syriza’S Debacle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Thoughts on the 25 January 2015 Election in Greece

GPSG Pamphlet No 4 First thoughts on the 25 January 2015 election in Greece Edited by Roman Gerodimos Copy editing: Patty Dohle Roman Gerodimos Pamphlet design: Ana Alania Cover photo: The Zappeion Hall, by Panoramas on Flickr Inside photos: Jenny Tolou Eveline Konstantinidis – Ziegler Spyros Papaspyropoulos (Flickr) Ana Alania Roman Gerodimos Published with the support of the Politics & Media Research Group, Bournemouth University Selection and editorial matter © Roman Gerodimos for the Greek Politics Specialist Group 2015 All remaining articles © respective authors 2015 All photos used with permission or under a Creative Commons licence Published on 2 February 2015 by the Greek Politics Specialist Group (GPSG) www.gpsg.org.uk Editorial | Roman Gerodimos Continuing a tradition that started in 2012, a couple of weeks ago the Greek Politics Specialist Group (GPSG) invited short commentaries from its members, affiliates and the broader academ- ic community, as a first ‘rapid’ reaction to the election results. The scale of the response was humbling and posed an editorial dilemma, namely whether the pamphlet should be limited to a small number of indicative perspectives, perhaps favouring more established voices, or whether it should capture the full range of viewpoints. As two of the founding principles and core aims of the GPSG are to act as a forum for the free exchange of ideas and also to give voice to younger and emerging scholars, it was decided that all contributions that met our editorial standards of factual accuracy and timely -

The Making of SYRIZA

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Panos Petrou The making of SYRIZA Published: June 11, 2012. http://socialistworker.org/print/2012/06/11/the-making-of-syriza Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. June 11, 2012 -- Socialist Worker (USA) -- Greece's Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA, has a chance of winning parliamentary elections in Greece on June 17, which would give it an opportunity to form a government of the left that would reject the drastic austerity measures imposed on Greece as a condition of the European Union's bailout of the country's financial elite. SYRIZA rose from small-party status to a second-place finish in elections on May 6, 2012, finishing ahead of the PASOK party, which has ruled Greece for most of the past four decades, and close behind the main conservative party New Democracy. When none of the three top finishers were able to form a government with a majority in parliament, a date for a new election was set -- and SYRIZA has been neck-and-neck with New Democracy ever since. Where did SYRIZA, an alliance of numerous left-wing organisations and unaffiliated individuals, come from? Panos Petrou, a leading member of Internationalist Workers Left (DEA, by its initials in Greek), a revolutionary socialist organisation that co-founded SYRIZA in 2004, explains how the coalition rose to the prominence it has today. -

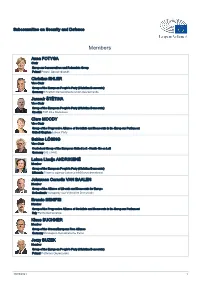

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

BIGGEST INEQUALITY SURGE SINCE 1980S

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 433 22 March 2017 50p/£1 Inside: BIGGEST INEQUALITY Keep the guard on the SURGE SINCE 1980s train! Strikes against driver-only operation spread. See page 10 Greece: a fourth memorandum? Theodora Polenta discusses the current political situation in Greece. See pages 6-7 The art of Buffy “If nothing is done to change [the] outlook, the current parlia - ment [2015-20] will go down as being the worst on record for in - come growth in the bottom half of the income distribution. “It will also represent the biggest rise in inequality since the end of the 1980s”. More page 5 On the 20th anniversary of the TV RICH AND series, Carrie Evans discusses its impact. See page 9 Join Labour! POOR: THE Grassroots Momentum: an opportunity almost missed GAP WIDENS See page 4 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org G20 deletion signals danger By Rhodri Evans From revolutionary to bourgeois minister When 20 governments met for the G20 summit in late 2008, at the worst of the global credit crash, their agreed joint state - Martin McGuinness ment included just one hard commitment: to resist protec - tionism, to avoid new trade By Gerry Bates minister, and made a series of real barriers. and symbolic concessions to union - Not perfectly, but on the whole, ism — signing up to support Police Martin McGuinness became a that commitment held, and Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), helped the slump level out in late revolutionary, by his own lights, and shaking the Queen’s hand in as a teenager, and ended his life 2009 rather than continuing June 2012, which he described as downwards for three or four as a bourgeois minister in a po - “in a symbolic way offering the litical system he had vowed to years as in the 1930s, when states hand of friendship to unionists”. -

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study Release Notes Sebastian Adrian Popa Hermann Schmitt Sara B Hobolt Eftichia Teperoglou Original release 1 January 2015 MZES, University of Mannheim Acknowledgement of the data Users of the data are kindly asked to acknowledge use of the data by always citing both the data and the accompanying release document. How to cite this data: Schmitt, Hermann; Popa, Sebastian A.; Hobolt, Sara B.; Teperoglou, Eftichia (2015): European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5160 Data file Version 2.0.0, doi:10.4232/1. 12300 and Schmitt H, Hobolt SB and Popa SA (2015) Does personalization increase turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, Online first available for download from: http://eup.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/06/03/1465116515584626.full How to cite this document: Sebastian Adrian Popa, Hermann Schmitt, Sara B. Hobolt, and Eftichia Teperoglou (2015) EES 2014 Voter Study Advance Release Notes. Mannheim: MZES, University of Mannheim. Acknowledgement of assistance The 2014 EES voter study was funded by a consortium of private foundations under the leadership of Volkswagen Foundation (the other partners are: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Stiftung Mercator, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian). It profited enormously from to synergies that emerged from the co-operation with the post-election survey funded by the European Parliament. Last but certainly not least, it benefited from the generous support of TNS Opinion who did the fieldwork in all the 28 member countries . The study would not have been possible the help of many colleagues, both members of the EES team and country experts form the wider academic community, who spent valuable time on the questionnaire and study preparation, often at very short notice. -

For a European Antifascist Movement Before It Is Too Late

For a European antifascist movement before it is too late... https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article3146 Anti-fascism For a European antifascist movement before it is too late... - IV Online magazine - 2013 - IV465 - October 2013 - Publication date: Monday 14 October 2013 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/5 For a European antifascist movement before it is too late... The launching press conference of the Greek Committee of the European Antifascist Initiative took place last Thursday 10 of October at the conference hall of the Greek Journalists' Union. The panel included the journalist and documentarist Aris Hatzistefanou (Debtocracy, Catastroika), the professor of International Law George Katrougalos, the Secretary of Syriza's Central Committee Dimitris Vitsas, the vice-president of Unicef-Hellas Sofia Tzitzikou, the Secretary of EEK (far-left) Savvas Michail, the MP of Syriza Dimitris Tsoukalas, the activist Yorgos Mitralias and the journalist Moisis Litsis. Among personalities present in the hall and supporting the European Antifascist Manifesto we noticed many Syriza MPs like Sofia Sakorafa and antifascist resistance national hero Manolis Glezos, the ex-president of the Journalist's Union D. Trimis, Unicef-Hellas president L. Kanellopoulos, the president of the Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen & Merchants (GSEVEE), members of Syriza's leadership, university professors, leading ecologists, the author of the book on Golden Dawn Dimitris Psarras and the president of the Association of Holocaust's Victims Descendents Marios Soussis. Comrade Petros Konstantinou, leader of the antiracist and antifascist movement KERFAA, took also the floor exposing his point of view.. -

Reshaping Politics of the Left and Centre in Greece After the 2014 EP Election Filippa Chatzistavrou and Sofia Michalaki

Commentary No. 21/ 10 September 2014 Reshaping politics of the left and centre in Greece after the 2014 EP election Filippa Chatzistavrou and Sofia Michalaki he European Parliament elections in Greece earlier this year highlighted a conundrum: that of minority political parties struggling to mobilise voters in the event of snap national elections in T spring 2015. The political landscape is confused and volatile; the right and extreme-right on the political spectrum are accorded a disproportionately large place in political debate, while ideological positioning by the centre and centre-left does not seem to be a major concern for political analysts. The radical left-wing SYRIZA party is attempting to maintain a ‘leftist’ profile while demonstrating its capacity to govern through a strategy of image normalisation. SYRIZA faces a profound challenge in defining a modern political programme in which policy-specific party positions will be clearly identified, and in which political engagement can be matched with concrete political proposals. This conundrum looks even more insoluble in the face of internal criticism about attempts by the party leadership to broaden its electoral base to be more inclusive. Electoral winners and political losers from across the spectrum Official electoral results showed SYRIZA to be the winner of the 2014 EP election. But if we look more closely at the results and compare them to those of the last national elections (2012), we see that despite a spectacular launch in 2012, SYRIZA recorded a loss of more than 100,000 votes in the EP election. This loss could partly be attributed to poor voter turnout, although traditionally in Greece the opposition significantly increases its vote share in EP elections. -

For a European Antifascist Movement

For A European Antifascist Movement By Yorgos Mitralias Region: Europe Global Research, June 27, 2013 Theme: Police State & Civil Rights CADTM and Socialist Project The deepening and generalization of the crisis to nearly all European countries makes it now possible to comprehend not only the crisis’s dynamic and characteristics, but also the priority tasks which a Left that does not surrender and keeps resisting ought to take on. 1. That is why we could henceforth evoke a trend toward the “Greecization” of, at least, the European south, insofar as countries such as Spain, Italy or even France, one after the other, find themselves confronted with a political scene that has been deeply and drastically changed, just like what has been going on in Greece for the last two to three years. To various extents, but in a clearer and clearer fashion, the pillar of their political system, say their traditionally prevailing two-party system, has entered a profound crisis (France, Spain) or more, is collapsing (Greece, Italy) in favour of often unheard of until those days political forces, belonging to both ends of the political scene. In no time, their two main (left and right) neoliberal parties, which had been keeping the power in turns – altogether, they used to gather 70 per cent, 80 per cent or even more of the votes, have now started to decline or even decompose. They are no longer granted more than 50 per cent, 40 per cent or even 30 per cent of the citizens’ preferences. Collapse of Social-Democracy 2. Even though the classical right has suffered too, the consequences of the alienation of citizens mainly impacted the social-democracy. -

A Weightless Hegemony

susan watkins Editorial A WEIGHTLESS HEGEMONY New Labour’s Role in the Neoliberal Order he Centre Left governments that dominated the North Atlantic zone up to the turn of the millennium have now all Tbut disappeared. Within six months of Bush’s victory in the United States, the Olive Tree coalition had crumbled before Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. The autumn of 2001 saw Social Democrats driven from office in Norway and Denmark. In April 2002 Kok’s Labour-led government resigned over a report pointing to Dutch troops’ complicity in the Srebrenica massacre. The following month, Jospin came in a humiliating third behind Chirac and Le Pen in the French presidential contest, and the Right triumphed in the legislative elections. In Germany, the spd–Green coalition clung on by a whisker, aided by providential floods. Though the sap retains its historic grip on Sweden it now lacks an absolute majority, and Persson was trounced in the 2003 campaign for euro entry. In Greece, where pasok has only been out of power for three years since 1981, Simitis squeaked back in 2000 with a 43.8 to 42.7 per cent lead. Within this landscape, Britain has been the conspicuous exception. In the United Kingdom alone a Centre Left government remains firmly in place, its grip on power strengthened, if anything, in its second term of office, and still enjoying a wide margin of electoral advantage. Both features—New Labour’s survival against the general turn of the polit- ical wheel, and the scale of its domestic predominance—set it apart within the oecd zone. -

Populist Parties a Journey Around the Continent’S New and Old Populist Parties

1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. As the publisher of this work, d|part wants to encourage the circulation of the work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore publish our work under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. This means that you can share, download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format. This is subject to Attribution — You must give appropriate credit to d|part and the authors listed above, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. Non Commercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. No Derivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material. To find out more go to www.creativecommons.org First published in 2018. © d|part. Some rights reserved. Keithstrasse 14, 10787 Berlin, Germany www.dpart.org Edited by Anne Heyer & Christine Hübner. We are grateful for the contributions of our authors: Konstantinos Kostagiannis, Timo Lochocki, Javier Martínez-Cantó, Agata Mazepus, Honorata Mazepus, Charlotte de Roon, Krisztian Simon, Maria Tyrberg, Ioannis Vlastaris. Title picture: “Linked” by Cali4beach via Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0. Europe’s new spectre: Populist parties A journey around the continent’s new and old populist parties Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................. 1 (Un-)democratic populism and new parties in Europe ......................................................................... 5 Anne Heyer 1 - The many transformations of Syriza ............................................................................................. -

Of National Politics

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/qoe Zooming in on the ‘Europeanisation’ of national politics: A comparative analysis of seven EU Citation: Mariano Torcal, Toni Rodon (2021) Zooming in on the ‘Europeanisation’ countries of national politics: A comparative anal- ysis of seven EU countries. Quaderni dell’Osservatorio elettorale – Italian Journal of Electoral Studies 84(1): 3-29. Mariano Torcal1,*, Toni Rodon2 doi: 10.36253/qoe-9585 1 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, ICREA Research Fellow, 0000-0002-0060-1522 Received: August 10, 2020 2 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 0000-0002-0546-4475 *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Accepted: March 24, 2021 Published: July 20, 2021 Abstract. This article empirically revisits and tests the effect of individual distance from parties on the EU integration dimension and on the left–right dimension for Copyright: © 2021 Mariano Torcal, Toni Rodon. This is an open access, peer- vote choice in both national and European elections. This analysis is based on the reviewed article published by Firenze unique European Election Study (EES) 2014 survey panel data from seven EU coun- University Press (http://www.fupress. tries. Our findings show that in most countries the effect of individual distance on com/qoe) and distributed under the the EU integration dimension is positive and significant for both European and terms of the Creative Commons Attri- national elections. Yet the effect of this dimension is not uniform across all seven bution License, which permits unre- countries, revealing two scenarios: one in which it is only relevant for Eurosceptic stricted use, distribution, and reproduc- voters and the other in which it is significant for voters of most parties in the system.