Paper Teperoglou & Tsatsanis EES Final Conference Nov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of Syriza: an Interview with Aristides Baltas

THE RISE OF SYRIZA: AN INTERVIEW WITH ARISTIDES BALTAS This interview with Aristides Baltas, the eminent Greek philosopher who was one of the founders of Syriza and is currently a coordinator of its policy planning committee, was conducted by Leo Panitch with the help of Michalis Spourdalakis in Athens on 29 May 2012, three weeks after Syriza came a close second in the first Greek election of 6 May, and just three days before the party’s platform was to be revealed for the second election of 17 June. Leo Panitch (LP): Can we begin with the question of what is distinctive about Syriza in terms of socialist strategy today? Aristides Baltas (AB): I think that independently of everything else, what’s happening in Greece does have a bearing on socialist strategy, which is not possible to discuss during the electoral campaign, but which will present issues that we’re going to face after the elections, no matter how the elections turn out. We haven’t had the opportunity to discuss this, because we are doing so many diverse things that we look like a chicken running around with its head cut off. But this is precisely why I first want to step back to 2008, when through an interesting procedure, Synaspismos, the main party in the Syriza coalition, formulated the main elements of the programme in a book of over 300 pages. The polls were showing that Syriza was growing in popularity (indeed we reached over 15 per cent in voting intentions that year), and there was a big pressure on us at that time, as we kept hearing: ‘you don’t have a programme; we don’t know who you are; we don’t know what you’re saying’. -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTION IN GREECE 7th July 2019 European New Democracy is the favourite in the Elections monitor Greek general election of 7th July Corinne Deloy On 26th May, just a few hours after the announcement of the results of the European, regional and local elections held in Greece, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA), whose party came second to the main opposition party, New Analysis Democracy (ND), declared: “I cannot ignore this result. It is for the people to decide and I am therefore going to request the organisation of an early general election”. Organisation of an early general election (3 months’ early) surprised some observers of Greek political life who thought that the head of government would call on compatriots to vote as late as possible to allow the country’s position to improve as much as possible. New Democracy won in the European elections with 33.12% of the vote, ahead of SYRIZA, with 23.76%. The Movement for Change (Kinima allagis, KINAL), the left-wing opposition party which includes the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), the Social Democrats Movement (KIDISO), the River (To Potami) and the Democratic Left (DIMAR), collected 7.72% of the vote and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), 5.35%. Alexis Tsipras had made these elections a referendum Costas Bakoyannis (ND), the new mayor of Athens, on the action of his government. “We are not voting belongs to a political dynasty: he is the son of Dora for a new government, but it is clear that this vote is Bakoyannis, former Minister of Culture (1992-1993) not without consequence. -

Greece Political Briefing: an Assessment of SYRIZA's Review

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 26, No. 1 (GR) Febr 2020 Greece political briefing: An assessment of SYRIZA’s review George N. Tzogopoulos 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 An assessment of SYRIZA’s review In February 2020 the central committee of SYRIZA approved the party’s review covering the period from January 2015 until July 2019. While the performance of SYRIZA after the summer of 2015 was largely based on bailout obligations and was efficient, its stance in the first semester of that year stigmatized not only the national economy but also the party itself. The review discusses successes and failures and constitutes a useful document in the effort of the main opposition party to learn by its mistakes and develop attractive governmental proposals. A few months after the general election of July 2019, the main opposition SYRIZA party is keeping a low profile in domestic politics. Its electoral defeat has required a period of self- criticism and internal debate in order for the party to gradually start formulating new policies which will perhaps allow it to win the next national election. Against this backdrop, three experienced politicians, former vice-President of the government Yiannis Dragasakis, former Shipping Minister Theodoros Dritsas and former Education Minister Aristides Baltas prepared a review of the party’s 4.5 administration year. The review was presented to SYRIZA’s central committee at the beginning of February 2020 and was subsequently approved. -

Greece Wave 3

GREECE WAVE 3 Pre-election Study June 2019 Marina Costa Lobo Efstratios-Ioannis Kartalis Nelson Santos Roberto Pannico Tiago Silva Table of Contents 1. Technical Report 2. Report Highlights 3. Most important Problem Facing Greece 4. Ideological Placement of Main Parties 5. Party identification 6. National Issues: Evaluation of the Economy 7. National Issues: Evaluation of the Current Syriza Government 8. National Issues: Economic situation 9. National Issues: Immigration 10. National Issues: PRESPA Agreement 11. Greece and the EU: Membership 12. Greece and the EU: Benefits of Membership 13. Greece and the EU: Political Integration? 14. Greece and the EU: Benefits of the Euro 15. Greece and the EU: Exit from the Euro 1. Technical Report This study is part of the MAPLE Project, ERC – European Research Council Grant, 682125, which aims to study the Politicisation of the EU before and after the Eurozone Crisis in Belgium, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain. In each of these countries an online panel will be carried out just before and just after the legislative elections. This report pertains to the pre-election panel of Greece legislative elections 2019 to be held on 7 July. Our questionnaire seeks to model the political context of political choices, and to understand the importance which European attitudes may have in voting behaviour. In Greece, we have partnered with Metron Analysis. We present in this report a number of political attitudes according to stated partisanship in Greece. We are interested in the way in which partisan preferences are related to political attitudes, including national issues as well as those pertaining to the EU. -

Greece and the Case of the 2012

! ! ! ! ! ! "#$$%$!&'(!)*$!+&,$!-.!)*$!/01/!23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!74$%)6-',! ! ! 84$)*&!9&,,64&:6,! ! ! 8!;$'6-#!<-'-#,!=*$,6,!;>?@6))$(!)-!! )*$!A$3&#)@$')!-.!B-46)6%&4!;%6$'%$C!! D'6E$#,6)F!-.!+&46.-#'6&C!;&'!A6$G-! 83#64!1,)C!/01H! ! ! /! =&?4$!-.!+-')$'),! +*&3)$#!1! 8'!I')#-(>%)6-'!)-!)*$!;6G'6.6%&'%$!-.!74$%)-#&4!;F,)$@,JJJJJJJJJJ!K! !+$')#&4!B>LL4$!-.!)*$!"#$$:!+&,$JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMJMMN! =*$!"#$$:!74$%)-#&4!;F,)$@JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMMJJJM10! =*$!O&#$!233-#)>'6)F!-.!)*$!/01/!"#$$:!74$%)6-',JJJJJJJJJJJJJM1P! +*&3)$#!/! 74$%)-#&4!=*$-#F!-.!23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!;F,)$@,JJJJJJJJJJJJJM/0! 23$'!&'(!+4-,$(!56,)!74$%)-#&4!=*$-#F!&'(!Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'JJMMJM//! +*&3)$#!H! B&#)F!;)#&)$GF!O$,$&#%*!A$,6G'JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMM/P! Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'!O$,$&#%*!A$,6G'JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMJJH1! +*&3)$#!K! B&#)F!;)#&)$GF!O$,>4),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMJHP! Q$@&4$!O$3#$,$')&)6-'!O$,>4),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMKH! Q$@&4$!+&'(6(&)$!O$,>4),R!S6''6'G!&'(!5-,6'G!B&#)6$,JJJJJJJMJJMMMKT! +*&3)$#!P! +-'%4>,6-',JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMJJJJMMPH! U6?46-G#&3*FJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMN/! 833$'(6VJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJNK! ! H! 56,)!-.!;F@?-4,C!Q6G>#$,C!=&?4$,! ! Q6G>#$!1R!;&@34$!-.!O$4&)6E$!O&':!Q-#@>4&JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJMMM/W! ! Q6G>#$!/R!;&@34$!A&)&,$)!-.!+&'(6(&)$,!! 7V%*&'G$(!-'!X$Y!A$@-%#&%F!A6,)#6%)!56,),JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJM/T! ! Q6G>#$!HR!;&@34$!A&)&,$)!-.!B$#%$')&G$! !! -.!Q$@&4$!+&'(6(&)$,!-'!X$Y!A$@-%#&%F!A6,)#6%)!56,),JJJJJJJJJJMH/! ! Q6G>#$!KR!X&)6-'&4!A&)&,$)!A6,34&F6'G!B$#%$')&G$!-.!+*&'G$! !! -

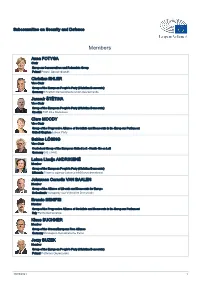

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

BIGGEST INEQUALITY SURGE SINCE 1980S

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 433 22 March 2017 50p/£1 Inside: BIGGEST INEQUALITY Keep the guard on the SURGE SINCE 1980s train! Strikes against driver-only operation spread. See page 10 Greece: a fourth memorandum? Theodora Polenta discusses the current political situation in Greece. See pages 6-7 The art of Buffy “If nothing is done to change [the] outlook, the current parlia - ment [2015-20] will go down as being the worst on record for in - come growth in the bottom half of the income distribution. “It will also represent the biggest rise in inequality since the end of the 1980s”. More page 5 On the 20th anniversary of the TV RICH AND series, Carrie Evans discusses its impact. See page 9 Join Labour! POOR: THE Grassroots Momentum: an opportunity almost missed GAP WIDENS See page 4 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org G20 deletion signals danger By Rhodri Evans From revolutionary to bourgeois minister When 20 governments met for the G20 summit in late 2008, at the worst of the global credit crash, their agreed joint state - Martin McGuinness ment included just one hard commitment: to resist protec - tionism, to avoid new trade By Gerry Bates minister, and made a series of real barriers. and symbolic concessions to union - Not perfectly, but on the whole, ism — signing up to support Police Martin McGuinness became a that commitment held, and Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), helped the slump level out in late revolutionary, by his own lights, and shaking the Queen’s hand in as a teenager, and ended his life 2009 rather than continuing June 2012, which he described as downwards for three or four as a bourgeois minister in a po - “in a symbolic way offering the litical system he had vowed to years as in the 1930s, when states hand of friendship to unionists”. -

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study

European Election Study 2014 EES 2014 Voter Study First Post-Electoral Study Release Notes Sebastian Adrian Popa Hermann Schmitt Sara B Hobolt Eftichia Teperoglou Original release 1 January 2015 MZES, University of Mannheim Acknowledgement of the data Users of the data are kindly asked to acknowledge use of the data by always citing both the data and the accompanying release document. How to cite this data: Schmitt, Hermann; Popa, Sebastian A.; Hobolt, Sara B.; Teperoglou, Eftichia (2015): European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5160 Data file Version 2.0.0, doi:10.4232/1. 12300 and Schmitt H, Hobolt SB and Popa SA (2015) Does personalization increase turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, Online first available for download from: http://eup.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/06/03/1465116515584626.full How to cite this document: Sebastian Adrian Popa, Hermann Schmitt, Sara B. Hobolt, and Eftichia Teperoglou (2015) EES 2014 Voter Study Advance Release Notes. Mannheim: MZES, University of Mannheim. Acknowledgement of assistance The 2014 EES voter study was funded by a consortium of private foundations under the leadership of Volkswagen Foundation (the other partners are: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Stiftung Mercator, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian). It profited enormously from to synergies that emerged from the co-operation with the post-election survey funded by the European Parliament. Last but certainly not least, it benefited from the generous support of TNS Opinion who did the fieldwork in all the 28 member countries . The study would not have been possible the help of many colleagues, both members of the EES team and country experts form the wider academic community, who spent valuable time on the questionnaire and study preparation, often at very short notice. -

Macedonians and the Greek Civil War

Macedonians and the Greek Civil War By By Naum Peiov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) Macedonians and the Greek Civil War Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada Originally published in Macedonian in June 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2015 by Naum Peiov & Risto Stefov e-book edition November 16, 2015 2 INDEX Foreword ............................................................................................4 PART ONE – The Greek Civil War 1945 – 1949 - Introduction ......8 CHAPTER ONE – Unilateral Civil War .........................................21 CHAPTER TWO - Restoration of the monarchy ............................52 CHAPTER THREE – ESTABLISHING A DEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENT..............................................................................72 CHAPTER FOUR - Withdrawal of the Democratic Army .............81 PART TWO - Macedonians in the Greek Civil War .......................91 CHAPTER FIVE – Systematic persecution of the Macedonian people ...............................................................................................91 CHAPTER SIX - RESISTANCE TO NEW PRESSURE .............127 CHAPTER SEVEN - RELATIONS BETWEEN NOF AND THE CPG................................................................................................136 -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period. -

Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 477,942 Km2

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Λάνδρος Χρίστος , Λάνδρος Χρίστος , Λάνδρος Χρίστος , Λάνδρος Χρίστος , Λάνδρος Χρίστος , Καμάρα Αφροδίτη , Ντόουσον Μαρία - Δήμητρα , Σπυροπούλου Βάσω Μετάφραση : Παπαδάκη Ειρήνη , Παπαδάκη Ειρήνη , Ντοβλέτης Ονούφριος , Ντοβλέτης Ονούφριος , Νάκας Ιωάννης , Καριώρης Παναγιώτης (23/3/2007) Περίληψη : Γενικές Πληροφορίες Area: 477,942 km2 Coastline length: 163 km Population: 33.814 Island capital and its population: Samos (6.236) Administrative structure: Region of North Aegean, Prefecture of Samos, Municipality of Vathy (Capital: Samos, 6.236), Municipality of Karlovasi (Capital: Neo Karlovasi, 5.740), Municipality of Marathokambos (Capital: Marathokambos, 1.329), Municipality of Pythagoreion (Capital: Pythagoreion, 1.327) Local newspapers: "Charavgi", "Samiakon Vima", "Samiakos Typos", "Samiaki Echo", "Samiaki" Local radio stations:Plus FM (89.4), Rock 9.35 (93.5), Radio Choros (94.2), Metamorfosis (95.0), Face FM (95.6), Samos FM (97.7), 2000 FM (99.8), Top FM (102.4), Armonia (103.2), Radio Vathy (102 FM) Local TV stations: TV Samos, Samiaki Tileorasi, TV 7 Samos Museums: Archaeological Museum of Samos, Archaeological Collection of Pythagoreion, Natural History Museum of the Aegean-Paleontological Museum of Samos-Constantinos and Maria Zimali Foundation, Karlovasi Historical and Folklore Museum, Folklore Museum of the N. Demetriou Foundation, Samos Ecclesiastical Museum, Samian Wine Museum, Pagonda Folklore Museum, Mavratzaioi Historical Museum Archaeological sites and monuments: The Heraion of