Europeans View Commercial Ties Between Britain and the American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Colonial Historical Society Société D'histoire

FRENCH COLONIAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY SOCIÉTÉ D’HISTOIRE COLONIALE FRANÇAISE 41ST Annual Meeting/41ème Congrès annuel 7-9 May/mai 2015 Binghamton, NY PROGRAM/PROGRAMME Thursday, May 7/jeudi 7 mai 8:00-12:30 Registration/Inscription 8:30-10:00 Welcome/Accueil (Arlington A) Alf Andrew Heggoy Book Prize Panel/ Remise du Prix Alf Andrew Heggoy Recipient/Récipiendaire: Elizabeth Foster, Tufts University, for her book Faith in Empire: Religion, Politics, and Colonial Rule in French Senegal, 1880-1940 (Stanford University Press, 2013) Discussant/Discutant: Ken Orosz, Buffalo State College 10:00-10:30 Coffee Break/Pause café 10:30-12:00 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1A Gender, Family, and Empire/Genre, famille, et empire (Arlington A) Chair/Modératrice: Jennifer Sessions, University of Iowa Caroline Campbell, University of North Dakota, “Claiming Frenchness through Family Heritage: Léon Sultan and the Popular Front’s Fight against Fascist Settlers in Interwar Morocco” Carolyn J. Eichner, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “Hubertine Auclert on Love, Marriage, and Divorce: The Family as a Site of Colonial Engagement” Nat Godley, Alverno College, “Public Assimilation and Personal Status: Gender relations and the mission civilisatrice among Algerian Jews” 1B Images, Representations, and Perceptions of Empire/Images, représentations et perceptions d’empire (Arlington B) Chair/Modératrice: Rebecca Scales, Rochester Institute of Technology Kylynn R. Jasinski, University of Pittsburgh, “Categorizing the Colonies: Architecture of the ‘yellow’ -

Society in Colonial Latin America with the Exception of Some Early Viceroys, Few Members of Spain’S Nobility Came to the New World

Spanish America and Brazil 475 Within Spanish America, the mining centers of Mexico and Peru eventually exercised global economic influence. American silver increased the European money supply, promoting com- mercial expansion and, later, industrialization. Large amounts of silver also flowed to Asia. Both Europe and the Iberian colonies of Latin America ran chronic trade deficits with Asia. As a result, massive amounts of Peruvian and Mexican silver flowed to Asia via Middle Eastern middlemen or across the Pacific to the Spanish colony of the Philippines, where it paid for Asian spices, silks, and pottery. The rich mines of Peru, Bolivia, and Mexico stimulated urban population growth as well as commercial links with distant agricultural and textile producers. The population of the city of Potosí, high in the Andes, reached 120,000 inhabitants by 1625. This rich mining town became the center of a vast regional market that depended on Chilean wheat, Argentine livestock, and Ecuadorian textiles. The sugar plantations of Brazil played a similar role in integrating the economy of the south Atlantic region. Brazil exchanged sugar, tobacco, and reexported slaves for yerba (Paraguayan tea), hides, livestock, and silver produced in neighboring Spanish colonies. Portugal’s increasing openness to British trade also allowed Brazil to become a conduit for an illegal trade between Spanish colonies and Europe. At the end of the seventeenth century, the discovery of gold in Brazil promoted further regional and international economic integration. Society in Colonial Latin America With the exception of some early viceroys, few members of Spain’s nobility came to the New World. -

Neo-European Worlds

Garner: Europeans in Neo-European Worlds 35 EUROPEANS IN NEO-EUROPEAN WORLDS: THE AMERICAS IN WORLD HISTORY by Lydia Garner In studies of World history the experience of the first colonial powers in the Americas (Spain, Portugal, England, and france) and the processes of creating neo-European worlds in the new environ- ment is a topic that has received little attention. Matters related to race, religion, culture, language, and, since of the middle of the last century of economic progress, have divided the historiography of the Americas along the lines of Anglo-Saxon vs. Iberian civilizations to the point where the integration of the Americas into World history seems destined to follow the same lines. But in the broader perspec- tive of World history, the Americas of the early centuries can also be analyzed as the repository of Western Civilization as expressed by its constituent parts, the Anglo-Saxon and the Iberian. When transplanted to the environment of the Americas those parts had to undergo processes of adaptation to create a neo-European world, a process that extended into the post-colonial period. European institu- tions adapted to function in the context of local socio/economic and historical realities, and in the process they created apparently similar European institutions that in reality became different from those in the mother countries, and thus were neo-European. To explore their experience in the Americas is essential for the integration of the history of the Americas into World history for comparative studies with the European experience in other regions of the world and for the introduction of a new perspective on the history of the Americas. -

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA and HIS OTHERS

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA AND HIS OTHERS (FREN GU4626) A study of Derrida’s work using as a guiding thread a comparison with contemporary “others” who have addressed the same question albeit from an antithetic point of view: 1) Derrida with Althusser on the question of historicity 2) Derrida with Deleuze on the question of alterity, focusing on their analyses of linguistic difference 3) Derrida with Habermas on the question of cosmopolitanism and hospitality Etienne Balibar THE 68-EFFECT IN FRENCH THEORY (FREN GU4625) A study of the relationship between the May 68 events in Paris and "French theory," with a focus on 1) “Power and Knowledge” (Foucault and Lacan); 2) “Desire” (Deleuze-Guattari and Irigaray); 3) “Reproduction” (Althusser and Bourdieu-Passeron). Antoine Compagnon PROUST VS. SAINTE-BEUVE (FREN GR8605) A seminar on the origins of the Proust’s novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, in the pamphlet Contre Sainte-Beuve, both an essay and a narrative drafted by Proust in 1908-1909. But who was Sainte-Beuve? And how did the monumental novel curiously emerge out of a quarrel with a 19th-century critic? We will also look at the various attempts to reconstitute the tentative Contre Sainte-Beuve, buried deep in the archeology of the Recherche. Souleymane Bachir Diagne DISCOVERING EXISTENCE (FREN GU4730) Modern science marking the end of the closed world meant that Earth, the abode of the human being, lost its natural position at the center of the universe. The passage from the Aristotelian closed world to the infinite universe of modern science raised the question of the meaning of human existence, which is the topic of the seminar. -

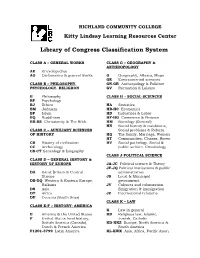

Library of Congress Classification System

RICHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE Kitty Lindsay Learning Resources Center Library of Congress Classification System CLASS A – GENERAL WORKS CLASS G – GEOGRAPHY & ANTHROPOLOGY AE Encyclopedias AG Dictionaries & general works G Geography, Atlases, Maps GE Environmental sciences CLASS B – PHILOSOPHY. GN-GR Anthropology & Folklore PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGIION GV Recreation & Leisure B Philosophy CLASS H – SOCIAL SCIENCES BF Psychology BJ Ethics HA Statistics BM Judaism HB-HC Economics BP Islam HD Industries & Labor BQ Buddhism HF-HG Commerce & Finance BR-BS Christianity & The Bible HM Sociology (General) HN Social history & conditions, CLASS C – AUXILIARY SCIENCES Social problems & Reform. OF HISTORY HQ The family, Marriage, Women HT Communities, Classes, Races CB History of civilization HV Social pathology. Social & CC Archaeology public welfare. Criminology CS-CT Genealogy & Biography CLASS J-POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASS D – GENERAL HISTORY & HISTORY OF EUROPE JA-JC Political science & Theory JF-JQ Political institutions & public DA Great Britain & Central administration Europe JS Local & Municipal DB-DQ Western & Eastern Europe, government. Balkans JV Colonies and colonization. DS Asia Emigration & immigration DT Africa JZ International relations. DU Oceania (South Seas) CLASS K – LAW CLASS E-F – HISTORY: AMERICA K Law in general E America & the United States KB Religious law, Islamic, F United States local history, Jewish, Catholic British America (Canada), KD-KKZ Europe, North America & Dutch & French America South America F1201-3799 Latin America KL-KWX -

Note: the 2020 Conference in Buffalo Was Cancelled Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Note: The 2020 conference in Buffalo was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. French Colonial History Society Preliminary Program Buffalo, May 28-30 mai, 2020 Thursday, May 28 / jeudi 31 mai 8:00-18:00 Registration/Inscription 9:00-10:30 Session 1 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1 A Celebrating the Empire in Francophone Contact Zones Moderator: TBD Berny Sèbe, University of Birmingham, “Celebrating the Empire in Geographical Borderlands: Literary Representations of Saharan Fortresses” Vladimir Kapor, University of Manchester, “‘Une célébration de l’unité de la France mondiale’? – Celebrations of La Semaine Coloniale française in the French Empire’s Peripheries” Matthew G. Stanard, Berry College, “Remembering the Colony across a Francophone Borderland: Celebrating Empire in Belgian Colonial Monuments after 1960” 1 B Painting and Representation Moderator: TBD Whitney Walton, Purdue University, “Imaging the Borders of Post-colonial French America: The Art of Charles-Alexandre Lesueur 1820s-1830s “ Caroline Herbelin, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, « La peinture lettrée en Annam au début de la colonisation française 1859-1924 « Agnieszka Anna Ficek, City University of New York, “Enlightened Cannibals and Primitive Princesses: the Inca Empire in the French Imagination” 1 C Racial Boundaries and the Civilizing Mission During and After the Great War Moderator: Richard Fogarty, University at Albany, SUNY Matt Patsis, University of Central Florida, “The Troupes Coloniales: A Comparative analysis of African American and French West African Soldiers in World War I” Mohamed Ait Abdelkader, Université Mouloud Mammeri (U.M.M.T.O.) de Tizi-Ouzou, « L’apport des “indigènes” dans la “mission civilisatrice” de l’empire colonial français » Elizabeth F. -

Library of Congress Classification System

Evergreen Valley College Library Outline of the Library of Congress Classification System The Evergreen Valley College Library uses the Library of Congress Classification System to organize its collection. An outline of the class system is presented here with breakout notations of popular areas within the collection. For further assistance, please consult a reference librarian. A—General Works E 300-453—Revolution to the Civil War, AE---Encyclopedias 1775-1861 E 398—Mexican War, 1846-1848 B—Philosophy, Psychology, Religion E 441-453—Slavery in the United States. BC—Logic Antislavery movements BF—Psychology E 456-655—Civil War period, 1861-65 E 660-738—Late nineteenth century, 1865- BH-BL—Aesthetics. Ethics BM—Judaism 1900 BP—Islam E 740-837—Twentieth Century BQ—Buddhism BR—Christianity F 1-975—United States Local History BS—The Bible F 856-870--California BX—Denominations & Sects F 1001-1145.2—British America F 1170—French America F 1201-3799—Latin America, Spanish C—Auxiliary Sciences of History America CT—Biography F 1201-1392—Mexico F 1219.73—Aztecs D—History: General and Old World F1421-1440—Central America D-DJ, DL-DR—History of Europe F1435—Mayas (General) DJK-DK—Eastern Europe G—Geography, Anthropology, Recreation DS—Asia GB—Physical Geography DT—Africa GC—Oceanography DU—Australia, New Zealand GN—Anthropology GR—Folklore E-F—History: America GT—Manners and Customs. Dress, E 11-143—America Costume, Fashion. E 51-73—Pre-Columbian America GV—Recreation E 75-99—Indians of North America H—Social Science E 99—Indian Tribes and Cultures HA—Statistics E 101-135—Discovery of America and HB-HC—Economics early explorations HD—Land. -

What Is Québécois Literature? Reflections on the Literary History of Francophone Writing in Canada

What is Québécois Literature? Reflections on the Literary History of Francophone Writing in Canada Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures, 28 Chapman, What is Québécois Literature.indd 1 30/07/2013 09:16:58 Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures Series Editors EDMUND SMYTH CHARLES FORSDICK Manchester Metropolitan University University of Liverpool Editorial Board JACQUELINE DUTTON LYNN A. HIGGINS MIREILLE ROSELLO University of Melbourne Dartmouth College University of Amsterdam MICHAEL SHERINGHAM DAVID WALKER University of Oxford University of Sheffield This series aims to provide a forum for new research on modern and contem- porary French and francophone cultures and writing. The books published in Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures reflect a wide variety of critical practices and theoretical approaches, in harmony with the intellectual, cultural and social developments which have taken place over the past few decades. All manifestations of contemporary French and francophone culture and expression are considered, including literature, cinema, popular culture, theory. The volumes in the series will participate in the wider debate on key aspects of contemporary culture. Recent titles in the series: 12 Lawrence R. Schehr, French 20 Pim Higginson, The Noir Atlantic: Post-Modern Masculinities: From Chester Himes and the Birth of the Neuromatrices to Seropositivity Francophone African Crime Novel 13 Mireille Rosello, The Reparative in 21 Verena Andermatt Conley, Spatial Narratives: Works of Mourning in Ecologies: Urban -

Topics Dept. Coord. Call

Selector Responsibility Areas CALL # TOPICS DEPT. COORD. A I 1 - 21 INDEXES REFERENCE BD AC 1 - 999 COLLECTIONS - SERIES ENGLISH BD AE 1 - 90 ENCYCLOPEDIAS REFERENCE BD AG 2 - 600 DICTIONARIES REFERENCE BD AM 1 - 501 MUSEUMS UNCLASSIFIED RW AN NEWSPAPERS COMM DP AP 1 - 271 PERIODICALS COMM DP AP 200 - 230 JUVENILE PERIODICALS JUV YR AS 1 - 945 ACADEMIES AND LEARNED SOCIETIES UNCLASSIFIED RW AY 10 - 2001 YEARBOOKS, ALMANACS REFERENCE BD AZ 20 - 999 HISTORY OF SCHOLARSHIP C & I YR B 1 - 5802 PHILOSOPHY PHILOSOPHY BD BC 1 - 199 LOGIC PHILOSOPHY BD BD 10 - 701 METAPHYSICS/ COSMOLOGY PHILOSOPHY BD BF 1 - 990 PSYCHOLOGY PSYCHOLOGY BD BF 1001 - 2055 PARAPSYCHOLOGY/OCCULT SCIENCE PSYCHOLOGY BD BH 1 - 301 AESTHETICS PHILOSOPHY BD BJ 1 - 1725 ETHICS PHILOSOPHY BD BJ 1801 - 2195 ETIQUETTE ANTHROPOLOGY KW BL 1 - 2790 RELIGION PHILOSOPHY BD BM 1 - 990 JUDAISM PHILOSOPHY BD BP 1 - 610 ISLAM PHILOSOPHY BD BQ 1 - 9800 BUDDHISM PHILOSOPHY BD BR 1 - 1725 CHRISTIANITY PHILOSOPHY BD BS 1 - 2970 THE BIBLE PHILOSOPHY BD BT 10 - 1480 DOCTRINE PHILOSOPHY BD BV 1 - 5099 PRACTICAL THEOLOGY PHILOSOPHY BD BX 1 - 9999 CHRISTIAN DENOMINATIONS PHILOSOPHY BD C 1 - 51 GENERAL HISTORY RK CB 3 - 482 HISTORY OF CIVILIZATONS HISTORY RK CC 1 - 960 ARCHAEOLOGY ANTHROPOLOGY KW CD 1 - 6471 ARCHIVES HISTORY RK CE 1 - 97 CALENDAR HISTORY RK CJ 1 - 6661 NUMISMATICS HISTORY RK CN 1 - 1355 INSCRIPTIONS HISTORY RK CR 1 - 6305 HERALDY HISTORY RK CS 1 - 3090 GENEALOGY HISTORY RK CT 21 - 9999 BIOGRAPHY UNCLASSIFIED D 1 - 2009 GENERAL HISTORY RK DA 1 - 995 GREAT BRITAIN HISTORY RK DAW -

The French Empire Remind Students of the Spanish Exper- Ience in the Americas

hsus_te_ch02_na_s02_s.fm Page 40 Tuesday, May 15, 2007v 9:48 AM A beaver ᮣ Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION Instruction A Profitable Fur Trade While the Spanish grew rich mining silver and gold in South America, the French profited from the fur trade SECTION in Canada. But the trade relied on good relations with Objectives the Indians, who hunted and traded valuable beaver As you teach this section, keep students pelts with the French. At times, conflicts with the Iroquois halted the trade. As one missionary reported, focused on the following objectives to help New France faced ruin: them answer the Section Focus Question and master core content. “At no time in the past were the beavers more plen- tiful in our lakes and rivers and more scarce in the • Explain how the fur trade affected the country’s stores....The war against the Iroquois has French and the Indians in North America. exhausted all the sources....The Montréal store has • Explain how and why Quebec was founded. not purchased a single beaver from the Natives in the • Describe the French expansion into past year. At Trois-Rivières, the few Natives that came were employed to defend the place where the enemy Louisiana. is expected. The store in Québec is the image of poverty.” —François Joseph Le Mercier, ᮡ French fur trader Relations des Jésuites, 1653 Prepare to Read Background Knowledge L3 The French Empire Remind students of the Spanish exper- ience in the Americas. Ask them to predict how the experiences of other Objectives Why It Matters Spain’s success with its American colonies encour- colonists might be different, depending • Explain how the fur trade affected the French aged other European nations to establish colonies. -

ED302438.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 438 SO 019 368 AUTHOR Glasrud, Clarence A., Ed. TITLE The Quiet Heritage = L'Heritage Tranquille. Proceedings from a Conference on the Contributions of the French to the Upper Midwest (Minneapolis, Minnesota, November 9, 1985). INSTITUTION Concordia Coll., Moorhead, Minn. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 1731).; Drawings, photographs, and colored reproductions of paintings will not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMCcbber Bookstore, Concordia College, Moorhead, MN 56560 ($9.50). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Studies; *French; *North American Culture; North Americans; United States History IDENTIFIERS French Canadians; *French Culture; French People; *Heritage; United States (Upper Midwest) ABSTRACT This book, containing the papers presented at a conference concerning the French contributions to the Upper Midwest region of the United States, includes:(1) "Contact and Consequence: An Introduction to Over 300 Years of French Presence in the Northwest" (V. Benoit);(2) "The French Voyageur and the Fur Trade" (J. T. Rivard); (3) "The Assimilation and Acculturation of French Canadians" (E. E. Gagne); (4) "History of Our Lady of Lourdes Church" (A. W. Moss);(5) "The Enhanced Economic Position of Women in French Colonial Illinois" (W. Briggs);(6) "Silkville: Fourierism on the Kansas Prairies" (L. D. Harris);(7) "The Structures of Everyday Life in a French Utopian Settlement in Iowa: The Case of the Icarians of Adams County, 1853-1898" (A. Prevos); (8) "France and America: A Minnesota Artist's Experience" (R. N. Coen); (9) "The Mute Heritage: Perspective on the French of America" (A. Renaud); (10) "French Presence in the Red River Valley, Part I: A History of the Metis to 1870" (V. -

Anti-Americanism and Americanophobia : a French Perspective

ANTI-AMERICANISM AND AMERICANOPHOBIA : A FRENCH PERSPECTIVE Denis Lacorne CERI/FNSP French anti-Americanism has never been as much the focus of debate as it is today. This is true both in France, where a crop of books has appeared on the subject, and in the United States, for reasons linked to the French refusal to support the American invasion of Iraq. Some authors have underlined the unchanging nature of the phenomenon, defining anti- Americanism as a historical “constant” since the 18th century, or again an endlessly repetitive “semantic block” to use Philippe Roger’s expression. Others, like Jean-François Revel, have tried to show what lay hidden behind such a fashionable ideology: a deep-rooted critique of economic liberalism and American democracy. Yet others, while rejecting the anti-American label, like Emmanuel Todd, have attempted to lift the veil and lay bare the weaknesses of American democracy and the extreme economic fragility of an American empire “in decline,” despite appearances.1 Contradictions and swings in public opinion What I propose to do here, rather than pick out historical constants, defend the virtues of the liberal model, or pontificate upon the inevitable decline of great empires, is to take a closer look at the contradictions of what I view as a changing and ambiguous phenomenon, a subject of frequent swings in public opinion. In The Rise and Fall of Anti-Americanism (1990) Jacques Rupnik and I pointed out that France is a heterogeneous country made up of countless different groups, every one of which has its “own” image of America, which frequently changes in the light of circumstances or political events.