Neo-European Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Role of the Privy Council and the Prerogative 3

Foreword The Privy Council is shrouded in mystery. As Patrick O’Connor points out, even its statutory definition is circular: the Privy Council is defined by the Interpretation Act 1978 as the members of ‘Her Majesty’s Honourable Privy Council’. Many people may have heard of its judicial committee, but its other roles emerge from the constitutional fog only occasionally – at their most controversial, to dispossess the Chagos Islanders of their home, more routinely to grant a charter to a university. Tracing its origin back to the twelfth or thirteen century, its continued existence, if considered at all, is regarded as vaguely charming and largely formal. But, as the vehicle that dispossessed those living on or near Diego Garcia, the Privy Council can still display the power that once it had more widely as an instrument of feudal rule. Many of its Orders in Council bypass Parliament but have the same force as democratically passed legislation. They are passed, unlike such legislation, without any express statement of compatibility with the European Convention on Human Rights. What is more, Orders in Council are not even published simultaneously with their passage. Two important orders relating to the treatment of the Chagos Islanders were made public only five days after they were passed. Patrick, originally inspired by his discovery of the essay that the great nineteenth century jurist Albert Venn Dicey wrote for his All Souls Fellowship, provides a fascinating account of the history and continuing role of the Privy Council. He concludes by arguing that its role, and indeed continued existence, should be subject to fundamental review. -

French Colonial Historical Society Société D'histoire

FRENCH COLONIAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY SOCIÉTÉ D’HISTOIRE COLONIALE FRANÇAISE 41ST Annual Meeting/41ème Congrès annuel 7-9 May/mai 2015 Binghamton, NY PROGRAM/PROGRAMME Thursday, May 7/jeudi 7 mai 8:00-12:30 Registration/Inscription 8:30-10:00 Welcome/Accueil (Arlington A) Alf Andrew Heggoy Book Prize Panel/ Remise du Prix Alf Andrew Heggoy Recipient/Récipiendaire: Elizabeth Foster, Tufts University, for her book Faith in Empire: Religion, Politics, and Colonial Rule in French Senegal, 1880-1940 (Stanford University Press, 2013) Discussant/Discutant: Ken Orosz, Buffalo State College 10:00-10:30 Coffee Break/Pause café 10:30-12:00 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1A Gender, Family, and Empire/Genre, famille, et empire (Arlington A) Chair/Modératrice: Jennifer Sessions, University of Iowa Caroline Campbell, University of North Dakota, “Claiming Frenchness through Family Heritage: Léon Sultan and the Popular Front’s Fight against Fascist Settlers in Interwar Morocco” Carolyn J. Eichner, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “Hubertine Auclert on Love, Marriage, and Divorce: The Family as a Site of Colonial Engagement” Nat Godley, Alverno College, “Public Assimilation and Personal Status: Gender relations and the mission civilisatrice among Algerian Jews” 1B Images, Representations, and Perceptions of Empire/Images, représentations et perceptions d’empire (Arlington B) Chair/Modératrice: Rebecca Scales, Rochester Institute of Technology Kylynn R. Jasinski, University of Pittsburgh, “Categorizing the Colonies: Architecture of the ‘yellow’ -

Society in Colonial Latin America with the Exception of Some Early Viceroys, Few Members of Spain’S Nobility Came to the New World

Spanish America and Brazil 475 Within Spanish America, the mining centers of Mexico and Peru eventually exercised global economic influence. American silver increased the European money supply, promoting com- mercial expansion and, later, industrialization. Large amounts of silver also flowed to Asia. Both Europe and the Iberian colonies of Latin America ran chronic trade deficits with Asia. As a result, massive amounts of Peruvian and Mexican silver flowed to Asia via Middle Eastern middlemen or across the Pacific to the Spanish colony of the Philippines, where it paid for Asian spices, silks, and pottery. The rich mines of Peru, Bolivia, and Mexico stimulated urban population growth as well as commercial links with distant agricultural and textile producers. The population of the city of Potosí, high in the Andes, reached 120,000 inhabitants by 1625. This rich mining town became the center of a vast regional market that depended on Chilean wheat, Argentine livestock, and Ecuadorian textiles. The sugar plantations of Brazil played a similar role in integrating the economy of the south Atlantic region. Brazil exchanged sugar, tobacco, and reexported slaves for yerba (Paraguayan tea), hides, livestock, and silver produced in neighboring Spanish colonies. Portugal’s increasing openness to British trade also allowed Brazil to become a conduit for an illegal trade between Spanish colonies and Europe. At the end of the seventeenth century, the discovery of gold in Brazil promoted further regional and international economic integration. Society in Colonial Latin America With the exception of some early viceroys, few members of Spain’s nobility came to the New World. -

Roles and Responsibilities of the Centres of Government

4. INSTITUTIONS Roles and responsibilities of the centres of government The centre of government (CoG), also known as the (26 countries). Australia and the Netherlands use a wide Cabinet Office, Office of the President, Privy Council, range of instruments, including performance management General Secretariat of the Government, among others, is and providing written guidance to ministries. Hungary and the structure that supports the Prime Minister and the Spain, on the other hand, use only regular cabinet meetings Council of Ministers (i.e. the regular meeting of government for this purpose. ministers). The CoG includes the body that serves the head The CoG is involved in strategic planning in all OECD countries, of government and the Council, as well as the office that except for Turkey – where the Ministry of Development is specifically serves the head of government (e.g. Prime mandated with this task. In six countries (Chile, Estonia, Minister’s Office). Iceland, Lithuania, Mexico and the United Kingdom) the The scope of the responsibilities assigned to such a responsibility is shared with the Ministry of Finance. structure varies largely among countries. In Greece, the CoG Transition planning and management falls under the sole is responsible for 11 functions, including communication responsibility of CoG in 21 countries and is shared with with the public, policy formulation and analysis. In Ireland other bodies in another 11. In five of these, each ministry is and Japan, only the preparation of cabinet meetings falls responsible for briefing the incoming government. Relations entirely under CoG responsibility. When considering both with Parliament fall within the scope of CoG responsibilities shared and exclusive tasks, the CoG has the broadest in all OECD countries. -

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA and HIS OTHERS

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA AND HIS OTHERS (FREN GU4626) A study of Derrida’s work using as a guiding thread a comparison with contemporary “others” who have addressed the same question albeit from an antithetic point of view: 1) Derrida with Althusser on the question of historicity 2) Derrida with Deleuze on the question of alterity, focusing on their analyses of linguistic difference 3) Derrida with Habermas on the question of cosmopolitanism and hospitality Etienne Balibar THE 68-EFFECT IN FRENCH THEORY (FREN GU4625) A study of the relationship between the May 68 events in Paris and "French theory," with a focus on 1) “Power and Knowledge” (Foucault and Lacan); 2) “Desire” (Deleuze-Guattari and Irigaray); 3) “Reproduction” (Althusser and Bourdieu-Passeron). Antoine Compagnon PROUST VS. SAINTE-BEUVE (FREN GR8605) A seminar on the origins of the Proust’s novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, in the pamphlet Contre Sainte-Beuve, both an essay and a narrative drafted by Proust in 1908-1909. But who was Sainte-Beuve? And how did the monumental novel curiously emerge out of a quarrel with a 19th-century critic? We will also look at the various attempts to reconstitute the tentative Contre Sainte-Beuve, buried deep in the archeology of the Recherche. Souleymane Bachir Diagne DISCOVERING EXISTENCE (FREN GU4730) Modern science marking the end of the closed world meant that Earth, the abode of the human being, lost its natural position at the center of the universe. The passage from the Aristotelian closed world to the infinite universe of modern science raised the question of the meaning of human existence, which is the topic of the seminar. -

Siam's Political Future : Documents from the End of the Absolute Monarchy

SIAM'S POLITICAL FUTURE: DOCUMENTS FROM THE END OF THE ABSOLUTE MONARCHY THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the hmnanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual cowitries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the program are carried on _both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an Wldergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Depaxatment of Asian Stu.dies, obtainable from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14850. 11 SIAM'S POLITICAL FUTURE: DOCUMENTS FROM THE END OF THE ABSOLUTE MONARCHY Compiled and edited with introductions by Benjamin A. -

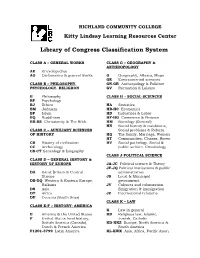

Library of Congress Classification System

RICHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE Kitty Lindsay Learning Resources Center Library of Congress Classification System CLASS A – GENERAL WORKS CLASS G – GEOGRAPHY & ANTHROPOLOGY AE Encyclopedias AG Dictionaries & general works G Geography, Atlases, Maps GE Environmental sciences CLASS B – PHILOSOPHY. GN-GR Anthropology & Folklore PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGIION GV Recreation & Leisure B Philosophy CLASS H – SOCIAL SCIENCES BF Psychology BJ Ethics HA Statistics BM Judaism HB-HC Economics BP Islam HD Industries & Labor BQ Buddhism HF-HG Commerce & Finance BR-BS Christianity & The Bible HM Sociology (General) HN Social history & conditions, CLASS C – AUXILIARY SCIENCES Social problems & Reform. OF HISTORY HQ The family, Marriage, Women HT Communities, Classes, Races CB History of civilization HV Social pathology. Social & CC Archaeology public welfare. Criminology CS-CT Genealogy & Biography CLASS J-POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASS D – GENERAL HISTORY & HISTORY OF EUROPE JA-JC Political science & Theory JF-JQ Political institutions & public DA Great Britain & Central administration Europe JS Local & Municipal DB-DQ Western & Eastern Europe, government. Balkans JV Colonies and colonization. DS Asia Emigration & immigration DT Africa JZ International relations. DU Oceania (South Seas) CLASS K – LAW CLASS E-F – HISTORY: AMERICA K Law in general E America & the United States KB Religious law, Islamic, F United States local history, Jewish, Catholic British America (Canada), KD-KKZ Europe, North America & Dutch & French America South America F1201-3799 Latin America KL-KWX -

8Th October 2019

ORDERS APPROVED AND BUSINESS TRANSACTED AT THE PRIVY COUNCIL HELD BY THE QUEEN AT BUCKINGHAM PALACE ON 8TH OCTOBER 2019 COUNSELLORS PRESENT The Rt Hon Jacob Rees-Mogg (Lord President) The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC The Rt Hon Grant Shapps The Rt Hon Theresa Villiers Privy The Rt Hon James Berry MP, the Rt Hon James Cleverly TD MP, Counsellors Dr Thérèse Coffey MP, the Rt Hon Oliver Dowden CBE MP, the Rt Hon Joseph Johnson MP, the Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng MP and the Rt Hon Mark Spencer MP were sworn as Members of Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council. Seven Orders appointing Conor Burns MP, Michael Ellis QC MP, Zac Goldsmith MP, Sir Bernard McCloskey, Alec Shelbrooke MP, Christopher Skidmore MP and Valerie Vaz MP Members of Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council. Secretaries of The Right Honourable Dr Thérèse Coffey MP was sworn one of State Her Majesty’s Principal Secretaries of State (Work and Pensions). Proclamations Five Proclamations:— 1. determining the specifications and designs for a new series of five thousand pound, two thousand pound, one thousand pound, five hundred pound and two hundred pound gold coins; and a new series of five pound silver coins; 2. determining the specifications and designs for a new series of ten pound gold coins; and a new series of ten pound, fifty pence and twenty pence silver coins; 3. determining the specifications and design for a new series of fifty pence coins in gold, silver and cupro-nickel marking the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union; 4. -

Note: the 2020 Conference in Buffalo Was Cancelled Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Note: The 2020 conference in Buffalo was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. French Colonial History Society Preliminary Program Buffalo, May 28-30 mai, 2020 Thursday, May 28 / jeudi 31 mai 8:00-18:00 Registration/Inscription 9:00-10:30 Session 1 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1 A Celebrating the Empire in Francophone Contact Zones Moderator: TBD Berny Sèbe, University of Birmingham, “Celebrating the Empire in Geographical Borderlands: Literary Representations of Saharan Fortresses” Vladimir Kapor, University of Manchester, “‘Une célébration de l’unité de la France mondiale’? – Celebrations of La Semaine Coloniale française in the French Empire’s Peripheries” Matthew G. Stanard, Berry College, “Remembering the Colony across a Francophone Borderland: Celebrating Empire in Belgian Colonial Monuments after 1960” 1 B Painting and Representation Moderator: TBD Whitney Walton, Purdue University, “Imaging the Borders of Post-colonial French America: The Art of Charles-Alexandre Lesueur 1820s-1830s “ Caroline Herbelin, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, « La peinture lettrée en Annam au début de la colonisation française 1859-1924 « Agnieszka Anna Ficek, City University of New York, “Enlightened Cannibals and Primitive Princesses: the Inca Empire in the French Imagination” 1 C Racial Boundaries and the Civilizing Mission During and After the Great War Moderator: Richard Fogarty, University at Albany, SUNY Matt Patsis, University of Central Florida, “The Troupes Coloniales: A Comparative analysis of African American and French West African Soldiers in World War I” Mohamed Ait Abdelkader, Université Mouloud Mammeri (U.M.M.T.O.) de Tizi-Ouzou, « L’apport des “indigènes” dans la “mission civilisatrice” de l’empire colonial français » Elizabeth F. -

The Government of Japan

THE GO\'ERNA[l<:XT OF JAIV\X=== I'.N' HAROLD S. (JL'ICLICV Professor of Political Science, University of Minnesota /\ S THE nineteenth century passed into its last quarter there was ^^ agitation in Ja])an for a people's parliament. Scarcely ten years had elapsed since the last of the ^'okngawa shoguns, Keiki, had surrendered his office to the youthful Enij)eror, Meiji. and with it the actual headship of the government, which his family had monopolized for three and a half centuries, in order that adminis- trative authority might he centralized and the empire enabled w "maintain its rank and dignity among the nations." During that decade political societies had appeared, led by no lesser persons than Okuma Shigenobu of the Hizen clan and Itagaki Taisuke of Tosa. provoked by the apparent intention of the leaders of the greater western clans, Choshu and Satsuma, to constitute themselves sole heirs of the governmental power which the Tokugawa daimyo had monopolized since the sixteenth century. Okuma and Itagaki, to- gether with other disgnmtled lesser clansmen, purposed to call into political life a new force, public opinion, to assist them in a strug- gle for a division of the Tokugawa legacy. On a winter's day in 1889 the agitation of the "politicians," as the leaders of the popular movement came to be called, in distinc- tion froin their opponents, the Satsuma and Choshu oligarchs, bore fruit. Before a distinguished company in the palace at Tokvo the constitution was read on February 11. a day already consecrated as Kigensetsu, the legendary date of the founding, in 660 B.C., of the imperial Yamato dynasty, which continues to the present mo- ment. -

Learning from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Political Science Dissertations Department of Political Science 5-9-2016 Extraterritorial Courts and States: Learning from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Harold Young Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_diss Recommended Citation Young, Harold, "Extraterritorial Courts and States: Learning from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_diss/40 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTRATERRITORIAL COURTS AND STATES: LEARNING FROM THE JUDICIAL COMMITTEE OF THE PRIVY COUNCIL by HAROLD AVNON YOUNG Under the Direction of Amy Steigerwalt, PhD ABSTRACT In 2015, South Africa withdrew from the International Criminal Court asserting United Nation’s Security Council bias in referring only African cases (Strydom October 15, 2015; Duggard 2013) and the United Kingdom reiterated a pledge to withdraw from the European Court of Human Rights, asserting that the court impinges on British sovereignty (Watt 2015). Both are examples of extraterritorial courts which are an important part of regional and global jurisprudence. To contribute to our understanding of the relationship between states and extraterritorial courts, I examine arguably the first and best example of an extraterritorial court, namely the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC). Drawing on 50 British Commonwealth states, this dissertation explores the factors influencing the decision to accede to an extraterritorial court and why some states subsequently opt to sever ties. -

Acting Regency: a Countermeasure Necessitated to Protect the Interest of the Hawaiian State

Establishing an Acting Regency: A Countermeasure Necessitated to Protect the Interest of the Hawaiian State David Keanu Sai, Ph.D. Establishing an Acting Regency: A Countermeasure Necessitated to Protect the Interest of the Hawaiian State November 28, 2009 Unable to deny the legal reality of the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and in light of the absence of any legitimate government in the Hawaiian Islands since 1893, the author and Donald A. Lewis, both being Hawaiian subjects, took deliberate political steps that would create severe legal consequences not only upon the occupant State, but also themselves. On December 10th 1995, both established the first co-partnership firm under Hawaiian Kingdom law since 1893, and, in order to protect the legal interest of the Hawaiian State, they would establish an acting Regent on December 15th as an officer de facto. Established under the legal doctrine of necessity, the acting Regency would be formed under and by virtue of Article 33 of the Constitution and laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as it stood prior to the landing of the U.S. troops on January 16th 1893. These include laws that existed prior to the revolution of July 6th 1887, which eventually caused the illegal landing of United States troops in 1893. At the core of these acts taken in December 1995 was the political existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Bateman states the “duty correlative of the right of political existence, is obviously that of political self-preservation; a duty the performance of which consists in constant efforts to preserve the principles of the political constitution.”1 Political self-preservation is adherence to the legal order of the State, whereas national self-preservation is where the principles of the constitution are no longer acknowledged, i.e.