French Americans.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in The

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in the 1930s” Paper for the Meetings of the Population Association of America Washington, DC 2011 Brian Gratton Faculty of History Arizona State University Emily Merchant ICPSR University of Michigan Draft: Please do not quote or cite without permission from the authors 1 Introduction In the wake of the economic collapse of the1930s, hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans returned to Mexico. Their repatriation has become an infamous episode in Mexican-American history, since public campaigns arose in certain locales to prompt persons of Mexican origin to leave. Antagonism toward immigrants appeared in many countries as unemployment spread during the Great Depression, as witnessed in the violent expulsion of the Chinese from northwestern Mexico in 1931 and 1932.1 In the United States, restriction on European immigration had already been achieved through the 1920s quota laws, and outright bans on categories of Asian immigrants had been in place since the 19th century. The mass immigration of Mexicans in the 1920s—in large part a product of the success of restrictionist policy—had made Mexicans the second largest and newest immigrant group, and hostility toward them rose across that decade.2 Mexicans became a target for nativism as the economic collapse heightened competition for jobs and as welfare costs and taxes necessary to pay for them rose. Still, there were other immigrants, including those from Canada, who received substantially less criticism, and the repatriation campaigns against Mexicans stand out in several locales for their virulence and coercive nature. Repatriation was distinct from deportation, a federal process. -

French Colonial Historical Society Société D'histoire

FRENCH COLONIAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY SOCIÉTÉ D’HISTOIRE COLONIALE FRANÇAISE 41ST Annual Meeting/41ème Congrès annuel 7-9 May/mai 2015 Binghamton, NY PROGRAM/PROGRAMME Thursday, May 7/jeudi 7 mai 8:00-12:30 Registration/Inscription 8:30-10:00 Welcome/Accueil (Arlington A) Alf Andrew Heggoy Book Prize Panel/ Remise du Prix Alf Andrew Heggoy Recipient/Récipiendaire: Elizabeth Foster, Tufts University, for her book Faith in Empire: Religion, Politics, and Colonial Rule in French Senegal, 1880-1940 (Stanford University Press, 2013) Discussant/Discutant: Ken Orosz, Buffalo State College 10:00-10:30 Coffee Break/Pause café 10:30-12:00 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1A Gender, Family, and Empire/Genre, famille, et empire (Arlington A) Chair/Modératrice: Jennifer Sessions, University of Iowa Caroline Campbell, University of North Dakota, “Claiming Frenchness through Family Heritage: Léon Sultan and the Popular Front’s Fight against Fascist Settlers in Interwar Morocco” Carolyn J. Eichner, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “Hubertine Auclert on Love, Marriage, and Divorce: The Family as a Site of Colonial Engagement” Nat Godley, Alverno College, “Public Assimilation and Personal Status: Gender relations and the mission civilisatrice among Algerian Jews” 1B Images, Representations, and Perceptions of Empire/Images, représentations et perceptions d’empire (Arlington B) Chair/Modératrice: Rebecca Scales, Rochester Institute of Technology Kylynn R. Jasinski, University of Pittsburgh, “Categorizing the Colonies: Architecture of the ‘yellow’ -

Society in Colonial Latin America with the Exception of Some Early Viceroys, Few Members of Spain’S Nobility Came to the New World

Spanish America and Brazil 475 Within Spanish America, the mining centers of Mexico and Peru eventually exercised global economic influence. American silver increased the European money supply, promoting com- mercial expansion and, later, industrialization. Large amounts of silver also flowed to Asia. Both Europe and the Iberian colonies of Latin America ran chronic trade deficits with Asia. As a result, massive amounts of Peruvian and Mexican silver flowed to Asia via Middle Eastern middlemen or across the Pacific to the Spanish colony of the Philippines, where it paid for Asian spices, silks, and pottery. The rich mines of Peru, Bolivia, and Mexico stimulated urban population growth as well as commercial links with distant agricultural and textile producers. The population of the city of Potosí, high in the Andes, reached 120,000 inhabitants by 1625. This rich mining town became the center of a vast regional market that depended on Chilean wheat, Argentine livestock, and Ecuadorian textiles. The sugar plantations of Brazil played a similar role in integrating the economy of the south Atlantic region. Brazil exchanged sugar, tobacco, and reexported slaves for yerba (Paraguayan tea), hides, livestock, and silver produced in neighboring Spanish colonies. Portugal’s increasing openness to British trade also allowed Brazil to become a conduit for an illegal trade between Spanish colonies and Europe. At the end of the seventeenth century, the discovery of gold in Brazil promoted further regional and international economic integration. Society in Colonial Latin America With the exception of some early viceroys, few members of Spain’s nobility came to the New World. -

Neo-European Worlds

Garner: Europeans in Neo-European Worlds 35 EUROPEANS IN NEO-EUROPEAN WORLDS: THE AMERICAS IN WORLD HISTORY by Lydia Garner In studies of World history the experience of the first colonial powers in the Americas (Spain, Portugal, England, and france) and the processes of creating neo-European worlds in the new environ- ment is a topic that has received little attention. Matters related to race, religion, culture, language, and, since of the middle of the last century of economic progress, have divided the historiography of the Americas along the lines of Anglo-Saxon vs. Iberian civilizations to the point where the integration of the Americas into World history seems destined to follow the same lines. But in the broader perspec- tive of World history, the Americas of the early centuries can also be analyzed as the repository of Western Civilization as expressed by its constituent parts, the Anglo-Saxon and the Iberian. When transplanted to the environment of the Americas those parts had to undergo processes of adaptation to create a neo-European world, a process that extended into the post-colonial period. European institu- tions adapted to function in the context of local socio/economic and historical realities, and in the process they created apparently similar European institutions that in reality became different from those in the mother countries, and thus were neo-European. To explore their experience in the Americas is essential for the integration of the history of the Americas into World history for comparative studies with the European experience in other regions of the world and for the introduction of a new perspective on the history of the Americas. -

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA and HIS OTHERS

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA AND HIS OTHERS (FREN GU4626) A study of Derrida’s work using as a guiding thread a comparison with contemporary “others” who have addressed the same question albeit from an antithetic point of view: 1) Derrida with Althusser on the question of historicity 2) Derrida with Deleuze on the question of alterity, focusing on their analyses of linguistic difference 3) Derrida with Habermas on the question of cosmopolitanism and hospitality Etienne Balibar THE 68-EFFECT IN FRENCH THEORY (FREN GU4625) A study of the relationship between the May 68 events in Paris and "French theory," with a focus on 1) “Power and Knowledge” (Foucault and Lacan); 2) “Desire” (Deleuze-Guattari and Irigaray); 3) “Reproduction” (Althusser and Bourdieu-Passeron). Antoine Compagnon PROUST VS. SAINTE-BEUVE (FREN GR8605) A seminar on the origins of the Proust’s novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, in the pamphlet Contre Sainte-Beuve, both an essay and a narrative drafted by Proust in 1908-1909. But who was Sainte-Beuve? And how did the monumental novel curiously emerge out of a quarrel with a 19th-century critic? We will also look at the various attempts to reconstitute the tentative Contre Sainte-Beuve, buried deep in the archeology of the Recherche. Souleymane Bachir Diagne DISCOVERING EXISTENCE (FREN GU4730) Modern science marking the end of the closed world meant that Earth, the abode of the human being, lost its natural position at the center of the universe. The passage from the Aristotelian closed world to the infinite universe of modern science raised the question of the meaning of human existence, which is the topic of the seminar. -

Franco-Americans in New England: Statistics from the American Community Survey

1 Franco-Americans in New England: Statistics from the American Community Survey Prepared for the Franco-American Taskforce October 24, 2012 James Myall 2 Introduction: As per the request of the State of Maine Legislative Franco-American Task Force, the following is an analysis of the Franco-American population in New England from data collected by the United States Census Bureau. This report accompanies ‘Franco-Americans in Maine’, which was also delivered to the Task Force, and is designed to determine whether the trends visible in Maine’s Franco-American population are reflected in other New England states (i.e. Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont). Information concerning methodology is repeated below for the sake of completeness. About the American Community Survey: The American Community Survey (ACS) is an annual survey conducted by the US Census Bureau to provide a broader snapshot of American life than is possible through the decennial census. The statistics gathered by the ACS are used by Congress and other agencies to determine the needs of Federal, State and local populations and agencies. The ACS is collected from randomly selected populations in every state to provide estimates which reflect American society as a whole. The data for this report was taken from the ACS using the online tool of the US Census Bureau, American Factfinder, <http://factfinder2.census.gov>. This report largely relies on the 2010 5-year survey, which allows analysis of smaller population units than the 1-year survey which is more accurate. Although the ACS surveys all Americans, the website allows users to filter data by several categories, including ancestry and ethnic origin, thus allowing a comprehensive picture of the Franco population. -

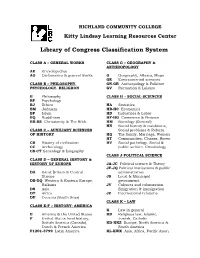

Library of Congress Classification System

RICHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE Kitty Lindsay Learning Resources Center Library of Congress Classification System CLASS A – GENERAL WORKS CLASS G – GEOGRAPHY & ANTHROPOLOGY AE Encyclopedias AG Dictionaries & general works G Geography, Atlases, Maps GE Environmental sciences CLASS B – PHILOSOPHY. GN-GR Anthropology & Folklore PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGIION GV Recreation & Leisure B Philosophy CLASS H – SOCIAL SCIENCES BF Psychology BJ Ethics HA Statistics BM Judaism HB-HC Economics BP Islam HD Industries & Labor BQ Buddhism HF-HG Commerce & Finance BR-BS Christianity & The Bible HM Sociology (General) HN Social history & conditions, CLASS C – AUXILIARY SCIENCES Social problems & Reform. OF HISTORY HQ The family, Marriage, Women HT Communities, Classes, Races CB History of civilization HV Social pathology. Social & CC Archaeology public welfare. Criminology CS-CT Genealogy & Biography CLASS J-POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASS D – GENERAL HISTORY & HISTORY OF EUROPE JA-JC Political science & Theory JF-JQ Political institutions & public DA Great Britain & Central administration Europe JS Local & Municipal DB-DQ Western & Eastern Europe, government. Balkans JV Colonies and colonization. DS Asia Emigration & immigration DT Africa JZ International relations. DU Oceania (South Seas) CLASS K – LAW CLASS E-F – HISTORY: AMERICA K Law in general E America & the United States KB Religious law, Islamic, F United States local history, Jewish, Catholic British America (Canada), KD-KKZ Europe, North America & Dutch & French America South America F1201-3799 Latin America KL-KWX -

Note: the 2020 Conference in Buffalo Was Cancelled Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Note: The 2020 conference in Buffalo was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. French Colonial History Society Preliminary Program Buffalo, May 28-30 mai, 2020 Thursday, May 28 / jeudi 31 mai 8:00-18:00 Registration/Inscription 9:00-10:30 Session 1 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1 A Celebrating the Empire in Francophone Contact Zones Moderator: TBD Berny Sèbe, University of Birmingham, “Celebrating the Empire in Geographical Borderlands: Literary Representations of Saharan Fortresses” Vladimir Kapor, University of Manchester, “‘Une célébration de l’unité de la France mondiale’? – Celebrations of La Semaine Coloniale française in the French Empire’s Peripheries” Matthew G. Stanard, Berry College, “Remembering the Colony across a Francophone Borderland: Celebrating Empire in Belgian Colonial Monuments after 1960” 1 B Painting and Representation Moderator: TBD Whitney Walton, Purdue University, “Imaging the Borders of Post-colonial French America: The Art of Charles-Alexandre Lesueur 1820s-1830s “ Caroline Herbelin, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, « La peinture lettrée en Annam au début de la colonisation française 1859-1924 « Agnieszka Anna Ficek, City University of New York, “Enlightened Cannibals and Primitive Princesses: the Inca Empire in the French Imagination” 1 C Racial Boundaries and the Civilizing Mission During and After the Great War Moderator: Richard Fogarty, University at Albany, SUNY Matt Patsis, University of Central Florida, “The Troupes Coloniales: A Comparative analysis of African American and French West African Soldiers in World War I” Mohamed Ait Abdelkader, Université Mouloud Mammeri (U.M.M.T.O.) de Tizi-Ouzou, « L’apport des “indigènes” dans la “mission civilisatrice” de l’empire colonial français » Elizabeth F. -

Improving Cultural Competence

Behavioral Health 5 Treatment for Major Racial and Ethnic Groups IN THIS CHAPTER John, 27, is an American Indian from a Northern Plains Tribe. He recently entered an outpatient treatment program in a midsized • Introduction Midwestern city to get help with his drinking and subsequent low • Counseling for African mood. John moved to the city 2 years ago and has mixed feelings and Black Americans about living there, but he does not want to return to the reserva- • Counseling for Asian tion because of its lack of job opportunities. Both John and his Americans, Native counselor are concerned that (with the exception of his girlfriend, Hawaiians, and Other Sandy, and a few neighbors) most of his current friends and Pacific Islanders coworkers are “drinking buddies.” John says his friends and family • Counseling for Hispanics on the reservation would support his recovery—including an uncle and Latinos and a best friend from school who are both in recovery—but his • Counseling for Native contact with them is infrequent. Americans • Counseling for White John says he entered treatment mostly because his drinking was Americans interfering with his job as a bus mechanic and with his relationship with his girlfriend. When the counselor asks new group members to tell a story about what has brought them to treatment, John explains the specific event that had motivated him. He describes having been at a party with some friends from work and watching one of his coworkers give a bowl of beer to his dog. The dog kept drinking until he had a seizure, and John was disgusted when peo- ple laughed. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover cover next page > title: American Indian Holocaust and Survival : A Population History Since 1492 Civilization of the American Indian Series ; V. 186 author: Thornton, Russell. publisher: University of Oklahoma Press isbn10 | asin: 080612220X print isbn13: 9780806122205 ebook isbn13: 9780806170213 language: English subject Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. publication date: 1987 lcc: E59.P75T48 1987eb ddc: 304.6/08997073 subject: Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. cover next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/cover.html[1/17/2011 5:09:37 PM] page_i < previous page page_i next page > Page i The Civilization of the American Indian Series < previous page page_i next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_i.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_v < previous page page_v next page > Page v American Indian Holocaust and Survival A Population History Since 1492 by Russell Thornton University of Oklahoma Press : Norman and London < previous page page_v next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_v.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_vi < previous page page_vi next page > Page vi BY RUSSELL THORNTON Sociology of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (With Mary K. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1980) The Urbanization of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (with Gary D. Sandefur and Harold G. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1982) We Shall Live Again: The 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dance Movements as Demographic Repitalization (New York, 1986) American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman, 1987) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thornton, Russell, 1942 American Indian holocaust and survival. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

From Model to Menace: French Intellectuals and American Civilization

Matsumoto Reiji(p163)6/2 04.9.6 3:17 PM ページ 163 The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 15 (2004) From Model to Menace: French Intellectuals and American Civilization Reiji MATSUMOTO* I The international debate about the Iraqi War once again brought to light a difference between Europe and America. Particularly striking was the French initiative to criticize American unilateralism, which aroused the resentment of the American people and provoked the Secretary of Defense to speak of “punishing” France. Jacques Chirac’s determined resistance to the Bush Administration’s war policy was countered with Donald Rumsfeld’s angry complaint against “old Europe.” Not only did the diplomats and politicians of the two countries reproach each other, but also in public opinion and popular sentiments, mutual antipathy has been growing on both sides of the Atlantic. The French government questioned the legitimacy of the Iraqi War and criticized American occupational policies. As far as these current issues are concerned, a diplomatic compromise will be possible and is to be reached in the process of international negotiation. The French gov- ernment’s bitter criticism of U.S. diplomacy, however, raised a more general question about the American approach to foreign affairs. In spite of the unanimous sympathy of the international community with American people after the disaster of September 11th, the Bush Administration’s Copyright © 2004 Reiji Matsumoto. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author.