Tejanos and Anglos in Nacogdoches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence

“I go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by James Robert Griffin August 2021 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by James Robert Griffin B.S., Kent State University, 2019 M.A., Kent State University, 2021 Approved by Kim M. Gruenwald , Advisor Kevin Adams , Chair, Department of History Mandy Munro-Stasiuk , Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………...……iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………..1 CHAPTERS I. Building a Colony: Austin leads the Texans Through the Difficulty of Settling Texas….9 Early Colony……………………………………………………………………………..11 The Fredonian Rebellion…………………………………………………………………19 The Law of April 6, 1830………………………………………………………………..25 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….32 II. Time of Struggle: Austin Negotiates with the Conventions of 1832 and 1833………….35 Civil War of 1832………………………………………………………………………..37 The Convention of 1833…………………………………………………………………47 Austin’s Arrest…………………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….59 III. Two Wars: Austin Guides the Texans from Rebellion to Independence………………..61 Imprisonment During a Rebellion……………………………………………………….63 War is our Only Resource……………………………………………………………….70 The Second War…………………………………………………………………………78 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….85 -

Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna ➢ in 1833 Santa Anna Was Elected President of Mexico, After Overthrowing Anastacio Bustamante

Road To Revolution PoliticAL uNREST IN TEXAS ➢ Haden Edwards received his Empresario contract from the Mexican Government in 1825. ➢ This contract allowed him to settle 800 families near Nacogdoches. ➢ Upon arrival, Edwards found that there had been families living there already. These “Old Settlers” were made up of Mexicans, Anglos, and Cherokees. ➢ Edwards’s contract required him to respect the property rights of the “old settlers” but he thought some of those titles were fake and demanded that people pay him additional fees for land they had already purchased. Fredonian Rebellion ➢ After Edward’s son-in-law was elected alcalde of the settlement, “old settlers” suspected fraud. ➢ Enraged, the “old settlers” got the Mexican Government to overturn the election and ultimately cancel Edwards’s contract on October 1826. ➢ Benjamin Edwards along with other supporters took action and declared themselves free from Mexican rule. Fredonian Rebellion (cont.) ➢ The Fredonian Decleration of Independance was issued on December 21, 1826 ➢ On January 1827, the Mexican government puts down the Fredonian Rebellion, collapsing the republic of Fredonia. MIer y Teran Report ➢ At this point, Mexican officials fear they are losing control of Texas. ➢ General Manuel de Mier y Teran was sent to examine the resources and indians of Texas & to help determine the formal boundary with Louisiana. Most importantly to determine how many americans lived in Texas and what their attitudes toward Mexico were. ➢ Mier y Teran came up with recommendations to weaken TX ties with the U.S. so Mexico can keep TX based on his report. His Report: His Recommendations: ➢ Mexican influence ➢ To increase trade between decreased as one moved TX & Mexico instead with northward & eastward. -

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in The

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in the 1930s” Paper for the Meetings of the Population Association of America Washington, DC 2011 Brian Gratton Faculty of History Arizona State University Emily Merchant ICPSR University of Michigan Draft: Please do not quote or cite without permission from the authors 1 Introduction In the wake of the economic collapse of the1930s, hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans returned to Mexico. Their repatriation has become an infamous episode in Mexican-American history, since public campaigns arose in certain locales to prompt persons of Mexican origin to leave. Antagonism toward immigrants appeared in many countries as unemployment spread during the Great Depression, as witnessed in the violent expulsion of the Chinese from northwestern Mexico in 1931 and 1932.1 In the United States, restriction on European immigration had already been achieved through the 1920s quota laws, and outright bans on categories of Asian immigrants had been in place since the 19th century. The mass immigration of Mexicans in the 1920s—in large part a product of the success of restrictionist policy—had made Mexicans the second largest and newest immigrant group, and hostility toward them rose across that decade.2 Mexicans became a target for nativism as the economic collapse heightened competition for jobs and as welfare costs and taxes necessary to pay for them rose. Still, there were other immigrants, including those from Canada, who received substantially less criticism, and the repatriation campaigns against Mexicans stand out in several locales for their virulence and coercive nature. Repatriation was distinct from deportation, a federal process. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives, and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1924 Richard Soash Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES STIRRING THE AMERICAN MELTING POT: MIDDLE EASTERN IMMIGRATION, THE PROGRESSIVES AND THE LEGAL CONSTRUCTION OF WHITENESS, 1880-1924 By RICHARD SOASH A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Richard Soash defended this thesis on March 7, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer Koslow Professor Directing Thesis Suzanne Sinke Committee Member Peter Garretson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my Grandparents: Evan & Verena Soash Richard & Patricia Fluck iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely thankful for both the academic and financial support that Florida State University has provided for me in the past two years. I would also like to express my gratitude to the FSU History Department for giving me the opportunity to pursue my graduate education here. My academic advisor and committee members – Dr. Koslow, Dr. Sinke, and Dr. Garretson – have been wonderful teachers and mentors during my time in the Master’s Program; I greatly appreciate their patience, humor, and knowledge, both inside and outside of the classroom. -

Arnoldo HERNANDEZ

Comercio a distancia y circulación regional. ♣ La feria del Saltillo, 1792-1814 Arnoldo Hernández Torres ♦ Para el siglo XVIII, el sistema económico mundial inicia la reorganización de los reinos en torno a la unidad nacional, a la cual se le conoce como mercantilismo en su última etapa. Una de las acciones que lo caracterizó fue la integración del mercado interno o nacional frente al mercado externo o internacional. Estrechamente ligados a la integración de los mercados internos o nacionales, aparecen los mercados regionales y locales, definidos tanto por la división política del territorio para su administración gubernamental como por las condiciones geográficas: el clima y los recursos naturales, entre otros aspectos. El proceso de integración del mercado interno en la Nueva España fue impulsado por las reformas borbónicas desde el último tercio del siglo XVIII hasta la independencia. Para el septentrión novohispano, particularmente la provincia de Coahuila, los cambios se reflejaron en el ámbito político, militar y económico. En el ámbito político los cambios fueron principalmente en la reorganización administrativa del territorio –la creación de la Comandancia de las Provincias Internas y de las Intendencias, así como la anexión de Saltillo y Parras a la provincia de Coahuila. En el ámbito militar se fortaleció el sistema de misiones y presidios a través de la política de poblamiento para consolidar la ocupación – el exterminio de indios “bárbaros” y la creación de nuevos presidios y misiones– y colonización del territorio –establecimiento -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

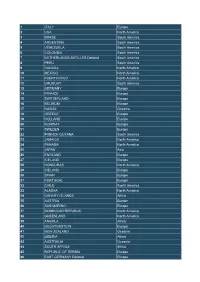

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

CASTRO's COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION in TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A

CASTRO'S COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION IN TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot thank all those who helped me produce this work, but some individuals must be mentioned. The idea of writing about Henri Castro was first suggested to me by Dr. Seymour V. Connor in a seminar at Texas Tech University. That idea started becoming a reality when James Menke of San Antonio offered the use of his files on Castro's colony. Menke's help and advice during the research phase of the project provided insights that only years of exposure to a subject can give. Without his support I would long ago have abandoned the project. The suggestions of my doctoral committee includ- ing Dr. John Wunder, Dr. Dan Flores, Dr. Robert Hayes, Dr. Otto Nelson, and Dr. Evelyn Montgomery helped me over some of the rough spots. My chairman, Dr. Alwyn Barr, was extremely patient with my halting prose. I learned much from him and I owe him much. I hope this product justifies the support I have received from all these individuals. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii LIST OF MAPS iv INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter I. THE EMPRESARIOS OF 1842 7 II. THE PROJECT BEGINS 39 III. A TOWN IS FOUNDED 6 8 IV. THE REORGANIZATION 97 V. SETTLING THE GRANT, 1845-1847 123 VI. THE COLONISTS: ADAPTING TO A NEW LIFE ... -

Chapter 14: the Young State

LoneThe Star State 1845–1876 Why It Matters As you study Unit 5, you will learn that the time from when Texas became a state until it left the Union and was later readmitted was an eventful period. Long-standing problems, such as the public debt and relations with Mexico, were settled. The tragedy of the Civil War and the events of Reconstruction shaped Texas politics for many years. Primary Sources Library See pages 692–693 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 5. Cowboy Dance by Jenne Magafan (1939) was commissioned for the Anson, Texas, post office to honor the day Texas was admitted to the Union as the twenty-eighth state. Today this study can be seen at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. 316 “I love Texas too well to bring strife and bloodshed upon her.” —Sam Houston, “Address to the People,” 1861 CHAPTER XX Chapter Title GEOGRAPHY&HISTORY KKINGING CCOTTONOTTON 1910 1880 Cotton Production 1880--1974 Bales of Cotton (Per County) Looking at the 1880 map, you can see 25,000 to more than 100,000 By 1910, cotton farming had spread that cotton farming only took place in into central and West Texas. Where East Texas during this time. Why do 1,000 to was production highest? you think this was so? 24,999 999 or less Cotton has been “king” throughout most of Texas 1800s, the cotton belt spread westward as new tech- history. Before the Civil War it was the mainstay of the nologies emerged. Better, stronger plows made it eas- economy.