The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776-1848 ------♦

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Colonial Historical Society Société D'histoire

FRENCH COLONIAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY SOCIÉTÉ D’HISTOIRE COLONIALE FRANÇAISE 41ST Annual Meeting/41ème Congrès annuel 7-9 May/mai 2015 Binghamton, NY PROGRAM/PROGRAMME Thursday, May 7/jeudi 7 mai 8:00-12:30 Registration/Inscription 8:30-10:00 Welcome/Accueil (Arlington A) Alf Andrew Heggoy Book Prize Panel/ Remise du Prix Alf Andrew Heggoy Recipient/Récipiendaire: Elizabeth Foster, Tufts University, for her book Faith in Empire: Religion, Politics, and Colonial Rule in French Senegal, 1880-1940 (Stanford University Press, 2013) Discussant/Discutant: Ken Orosz, Buffalo State College 10:00-10:30 Coffee Break/Pause café 10:30-12:00 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1A Gender, Family, and Empire/Genre, famille, et empire (Arlington A) Chair/Modératrice: Jennifer Sessions, University of Iowa Caroline Campbell, University of North Dakota, “Claiming Frenchness through Family Heritage: Léon Sultan and the Popular Front’s Fight against Fascist Settlers in Interwar Morocco” Carolyn J. Eichner, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “Hubertine Auclert on Love, Marriage, and Divorce: The Family as a Site of Colonial Engagement” Nat Godley, Alverno College, “Public Assimilation and Personal Status: Gender relations and the mission civilisatrice among Algerian Jews” 1B Images, Representations, and Perceptions of Empire/Images, représentations et perceptions d’empire (Arlington B) Chair/Modératrice: Rebecca Scales, Rochester Institute of Technology Kylynn R. Jasinski, University of Pittsburgh, “Categorizing the Colonies: Architecture of the ‘yellow’ -

Society in Colonial Latin America with the Exception of Some Early Viceroys, Few Members of Spain’S Nobility Came to the New World

Spanish America and Brazil 475 Within Spanish America, the mining centers of Mexico and Peru eventually exercised global economic influence. American silver increased the European money supply, promoting com- mercial expansion and, later, industrialization. Large amounts of silver also flowed to Asia. Both Europe and the Iberian colonies of Latin America ran chronic trade deficits with Asia. As a result, massive amounts of Peruvian and Mexican silver flowed to Asia via Middle Eastern middlemen or across the Pacific to the Spanish colony of the Philippines, where it paid for Asian spices, silks, and pottery. The rich mines of Peru, Bolivia, and Mexico stimulated urban population growth as well as commercial links with distant agricultural and textile producers. The population of the city of Potosí, high in the Andes, reached 120,000 inhabitants by 1625. This rich mining town became the center of a vast regional market that depended on Chilean wheat, Argentine livestock, and Ecuadorian textiles. The sugar plantations of Brazil played a similar role in integrating the economy of the south Atlantic region. Brazil exchanged sugar, tobacco, and reexported slaves for yerba (Paraguayan tea), hides, livestock, and silver produced in neighboring Spanish colonies. Portugal’s increasing openness to British trade also allowed Brazil to become a conduit for an illegal trade between Spanish colonies and Europe. At the end of the seventeenth century, the discovery of gold in Brazil promoted further regional and international economic integration. Society in Colonial Latin America With the exception of some early viceroys, few members of Spain’s nobility came to the New World. -

Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the Antebellum Southern United States

Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 3Plantation No. 3, July 2003, Slavery pp. 289–332. and Economic Development 289 Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the Antebellum Southern United States CHARLES POST The relationship of plantation slavery in the Americas to economic and social development in the regions it was dominant has long been a subject of scholarly debate. The existing literature is divided into two broad interpretive models – ‘planter capitalism’ (Fogel and Engerman, Fleisig) and the ‘pre-bourgeois civilization’ (Genovese, Moreno-Fraginals). While each grasps aspects of plantation slavery’s dynamics, neither provides a consistent and coherent his- torical or theoretical account of slavery’s impact on economic development because they focus on the subjective motivations of economic actors (planters or slaves) independent of their social context. Borrowing Robert Brenner’s concept of ‘social property relations’, the article presents an alternative analysis of the dynamics of plantation slavery and their relation to economic develop- ment in the regions it dominated. Keywords: plantation slavery, capitalism, USA, world market, agrarian class structure INTRODUCTION From the moment that plantation slavery came under widespread challenge in Europe and the Americas in the late eighteenth century, its economic impact has been hotly debated. Both critics and defenders linked the political and moral aspects of slavery with its social and economic effects on the plantation regions Charles Post, Sociology Department, Sarah Lawrence College, 1 Mead Way, Bronxville, NY 10708- 5999, USA. e-mail: [email protected] (until 30 August 2003). Department of Social Science, Borough of Manhattan Community College-CUNY, 199 Chambers Street, New York, NY 10007, USA. -

Neo-European Worlds

Garner: Europeans in Neo-European Worlds 35 EUROPEANS IN NEO-EUROPEAN WORLDS: THE AMERICAS IN WORLD HISTORY by Lydia Garner In studies of World history the experience of the first colonial powers in the Americas (Spain, Portugal, England, and france) and the processes of creating neo-European worlds in the new environ- ment is a topic that has received little attention. Matters related to race, religion, culture, language, and, since of the middle of the last century of economic progress, have divided the historiography of the Americas along the lines of Anglo-Saxon vs. Iberian civilizations to the point where the integration of the Americas into World history seems destined to follow the same lines. But in the broader perspec- tive of World history, the Americas of the early centuries can also be analyzed as the repository of Western Civilization as expressed by its constituent parts, the Anglo-Saxon and the Iberian. When transplanted to the environment of the Americas those parts had to undergo processes of adaptation to create a neo-European world, a process that extended into the post-colonial period. European institu- tions adapted to function in the context of local socio/economic and historical realities, and in the process they created apparently similar European institutions that in reality became different from those in the mother countries, and thus were neo-European. To explore their experience in the Americas is essential for the integration of the history of the Americas into World history for comparative studies with the European experience in other regions of the world and for the introduction of a new perspective on the history of the Americas. -

A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-23-2011 12:00 AM A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877 Marise Bachand University of Western Ontario Supervisor Margaret M.R. Kellow The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Marise Bachand 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Bachand, Marise, "A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South, 1790-1877" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 249. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/249 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SEASON IN TOWN: PLANTATION WOMEN AND THE URBAN SOUTH, 1790-1877 Spine title: A Season in Town: Plantation Women and the Urban South Thesis format: Monograph by Marise Bachand Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Marise Bachand 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Margaret M.R. Kellow Dr. Charlene Boyer Lewis ____________________ Dr. Monda Halpern ____________________ Dr. Robert MacDougall ____________________ Dr. -

A Periodisation of Globalisation According to the Mauritian Integration Into the International Sugar Commodity Chain (1825-2005)1

AA ppeerriiooddiissaattiioonn ooff gglloobbaalliissaattiioonn aaccccoorrddiinngg ttoo tthhee MMaauurriittiiaann iinntteeggrraattiioonn iinnttoo tthhee iinntteerrnnaattiioonnaall ssuuggaarr ccoommmmooddiittyy cchhaaiinn ((11882255--22000055)) PPaattrriicckk NNeevveelliinngg University of Berne May 2012 Copyright © Patrick Neveling, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Commodities of Empire Project, The Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA Commodities of Empire Working Paper No.18 ISSN: 1756-0098 A periodisation of globalisation according to the Mauritian integration into the international sugar commodity chain (1825-2005)1 Patrick Neveling (University of Berne) This paper shows that the analysis of commodity chains (CC) can be fruitfully employed to respond to recent calls in the field of global/world history for a periodisation of globalisation. 2 The CC approach is ideally suited for advancing global historians’ understanding of the way that particular places are positioned within a changing capitalist world system. This is important because it is this capitalist world system that ultimately defines globalisation in a particular place and therefore also the periodisation of globalisation. The place to be studied in this paper is Mauritius, a small island in the Western Indian Ocean that has a very particular history of colonial and postcolonial integration into the capitalist world system. -

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA and HIS OTHERS

Etienne Balibar DERRIDA AND HIS OTHERS (FREN GU4626) A study of Derrida’s work using as a guiding thread a comparison with contemporary “others” who have addressed the same question albeit from an antithetic point of view: 1) Derrida with Althusser on the question of historicity 2) Derrida with Deleuze on the question of alterity, focusing on their analyses of linguistic difference 3) Derrida with Habermas on the question of cosmopolitanism and hospitality Etienne Balibar THE 68-EFFECT IN FRENCH THEORY (FREN GU4625) A study of the relationship between the May 68 events in Paris and "French theory," with a focus on 1) “Power and Knowledge” (Foucault and Lacan); 2) “Desire” (Deleuze-Guattari and Irigaray); 3) “Reproduction” (Althusser and Bourdieu-Passeron). Antoine Compagnon PROUST VS. SAINTE-BEUVE (FREN GR8605) A seminar on the origins of the Proust’s novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, in the pamphlet Contre Sainte-Beuve, both an essay and a narrative drafted by Proust in 1908-1909. But who was Sainte-Beuve? And how did the monumental novel curiously emerge out of a quarrel with a 19th-century critic? We will also look at the various attempts to reconstitute the tentative Contre Sainte-Beuve, buried deep in the archeology of the Recherche. Souleymane Bachir Diagne DISCOVERING EXISTENCE (FREN GU4730) Modern science marking the end of the closed world meant that Earth, the abode of the human being, lost its natural position at the center of the universe. The passage from the Aristotelian closed world to the infinite universe of modern science raised the question of the meaning of human existence, which is the topic of the seminar. -

BLACK LONDON Life Before Emancipation

BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation ^^^^k iff'/J9^l BHv^MMiai>'^ii,k'' 5-- d^fli BP* ^B Br mL ^^ " ^B H N^ ^1 J '' j^' • 1 • GRETCHEN HOLBROOK GERZINA BLACK LONDON Other books by the author Carrington: A Life BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation Gretchen Gerzina dartmouth college library Hanover Dartmouth College Library https://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/digital/publishing/ © 1995 Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina All rights reserved First published in the United States in 1995 by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey First published in Great Britain in 1995 by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd. The Library of Congress cataloged the paperback edition as: Gerzina, Gretchen. Black London: life before emancipation / Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-8135-2259-5 (alk. paper) 1. Blacks—England—London—History—18th century. 2. Africans— England—London—History—18th century. 3. London (England)— History—18th century. I. title. DA676.9.B55G47 1995 305.896´0421´09033—dc20 95-33060 CIP To Pat Kaufman and John Stathatos Contents Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi 1. Paupers and Princes: Repainting the Picture of Eighteenth-Century England 1 2. High Life below Stairs 29 3. What about Women? 68 4. Sharp and Mansfield: Slavery in the Courts 90 5. The Black Poor 133 6. The End of English Slavery 165 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index Illustrations (between pages 116 and 111) 1. 'Heyday! is this my daughter Anne'. S.H. Grimm, del. Pub lished 14 June 1771 in Drolleries, p. 6. Courtesy of the Print Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 2. -

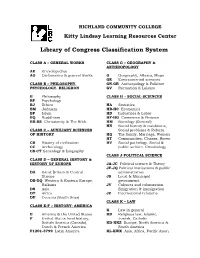

Library of Congress Classification System

RICHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE Kitty Lindsay Learning Resources Center Library of Congress Classification System CLASS A – GENERAL WORKS CLASS G – GEOGRAPHY & ANTHROPOLOGY AE Encyclopedias AG Dictionaries & general works G Geography, Atlases, Maps GE Environmental sciences CLASS B – PHILOSOPHY. GN-GR Anthropology & Folklore PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGIION GV Recreation & Leisure B Philosophy CLASS H – SOCIAL SCIENCES BF Psychology BJ Ethics HA Statistics BM Judaism HB-HC Economics BP Islam HD Industries & Labor BQ Buddhism HF-HG Commerce & Finance BR-BS Christianity & The Bible HM Sociology (General) HN Social history & conditions, CLASS C – AUXILIARY SCIENCES Social problems & Reform. OF HISTORY HQ The family, Marriage, Women HT Communities, Classes, Races CB History of civilization HV Social pathology. Social & CC Archaeology public welfare. Criminology CS-CT Genealogy & Biography CLASS J-POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASS D – GENERAL HISTORY & HISTORY OF EUROPE JA-JC Political science & Theory JF-JQ Political institutions & public DA Great Britain & Central administration Europe JS Local & Municipal DB-DQ Western & Eastern Europe, government. Balkans JV Colonies and colonization. DS Asia Emigration & immigration DT Africa JZ International relations. DU Oceania (South Seas) CLASS K – LAW CLASS E-F – HISTORY: AMERICA K Law in general E America & the United States KB Religious law, Islamic, F United States local history, Jewish, Catholic British America (Canada), KD-KKZ Europe, North America & Dutch & French America South America F1201-3799 Latin America KL-KWX -

Outlines of a Model of Pure Plantation Economr By

III. THE MECHANISM OF PLANTATION-TYPE ECONOMIES Outlines of a Model of Pure Plantation Economr By LLOYD BEST I. A PARTIAL TYPOLOGY OF ECONOMIC SYSTEMS The larger studyl of which this outline essay forms a part is concerned with the comparative study of economic systems. Following Myrdal2 and Seers3, we have taken the view that economic theory in the underdeveloped regions at any rate, can profit by relaxing its unwitting pre-occupation with the special case of the North Atlantic countries, and by proceeding to a typ- ology of structures4 each having characteristic laws of motion. s Plantation Economy, the type which we have selected for intensive study, falls within the general class of externally-propelled economies.5 Specifically, we isolate Hinterland Economy which can be further distinguished, for ex- ample, from Metropolitan Economy. In the latter, too, the adjustment pro- cess centres on foreign trade and payments but the locus of discretion and choice is at home and it is by this variable that we differentiate. Hinterland economy, indeed, is what is at the discretion of metropolitan economy. The re- lationship between the two may be described, summarily at this point, as mercantilist. In this designation inheres certain specifications regarding what may be called the general institutional framework of collaboration betweeen the two. It will suffice here to note the five major rules of the game, as it were. First, there is the most general provision which defines exclusive spheres of influence of a metropolis and the limitations on external intercourse for the hinterland. In the real world there have been, and still are, many ex- amples of this: the Inter-American System, the British Commonwealth, the French Community, the centrally-planned economies, and so on. -

Note: the 2020 Conference in Buffalo Was Cancelled Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Note: The 2020 conference in Buffalo was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. French Colonial History Society Preliminary Program Buffalo, May 28-30 mai, 2020 Thursday, May 28 / jeudi 31 mai 8:00-18:00 Registration/Inscription 9:00-10:30 Session 1 Concurrent Panels/Ateliers en parallèle 1 A Celebrating the Empire in Francophone Contact Zones Moderator: TBD Berny Sèbe, University of Birmingham, “Celebrating the Empire in Geographical Borderlands: Literary Representations of Saharan Fortresses” Vladimir Kapor, University of Manchester, “‘Une célébration de l’unité de la France mondiale’? – Celebrations of La Semaine Coloniale française in the French Empire’s Peripheries” Matthew G. Stanard, Berry College, “Remembering the Colony across a Francophone Borderland: Celebrating Empire in Belgian Colonial Monuments after 1960” 1 B Painting and Representation Moderator: TBD Whitney Walton, Purdue University, “Imaging the Borders of Post-colonial French America: The Art of Charles-Alexandre Lesueur 1820s-1830s “ Caroline Herbelin, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, « La peinture lettrée en Annam au début de la colonisation française 1859-1924 « Agnieszka Anna Ficek, City University of New York, “Enlightened Cannibals and Primitive Princesses: the Inca Empire in the French Imagination” 1 C Racial Boundaries and the Civilizing Mission During and After the Great War Moderator: Richard Fogarty, University at Albany, SUNY Matt Patsis, University of Central Florida, “The Troupes Coloniales: A Comparative analysis of African American and French West African Soldiers in World War I” Mohamed Ait Abdelkader, Université Mouloud Mammeri (U.M.M.T.O.) de Tizi-Ouzou, « L’apport des “indigènes” dans la “mission civilisatrice” de l’empire colonial français » Elizabeth F. -

The Factory V. the Plantation: Northern and Southern Economies on the Eve of the Civil War

The Factory v. the Plantation: Northern and Southern Economies on the Eve of the Civil War An Online Professional Development Seminar Peter Coclanis Director of the Global Research Institute Albert R. Newsome Professor UNC at Chapel Hill National Humanities Center Fellow We will begin promptly on the hour. The silence you hear is normal. If you do not hear anything when the images change, e-mail Caryn Koplik [email protected] for assistance. The Factory v. the Plantation GOALS To deepen understanding of the economic differences between the North and the South that contributed to the Civil War To provide fresh primary resources and instructional approaches for use with students americainclass.org 2 The Factory v. the Plantation FROM THE FORUM Challenges, Issues, Questions How did slave labor compare with free labor in terms of cost of production, profitability, and working conditions? Did ―good‖ treatment increase the productivity of slave labor? Did ―bad‖ treatment lessen it? How did families fare under slavery and under conditions of free labor? See ―How Slavery Affected African American Families‖ by Heather Williams in Freedom’s Story from the National Humanities Center To what extent did Northern factories depend on Southern plantations for their economic success and stability? americainclass.org 3 The Factory v. the Plantation FROM THE FORUM Challenges, Issues, Questions Why did the North permit slavery to continue in the South as long as it did? Would slavery have survived had the country managed to avoid the Civil War? How did the plantation economy work? How did economic issues influence the coming of the Civil War? How did economics influence Northern attitudes toward the South and slavery? americainclass.org 4 The Factory v.