Justice and Equality Movement (JEM)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The LRA in Kafia Kingi

The LRA in Kafia Kingi The suspension of the Ugandan army operation in the Central African Republic (CAR) following the overthrow of the CAR regime in March 2013 may have given some respite to the LRA, which by the first quarter of 2013 appeared to be at its weakest in its long history. As of May 2013, there were some 500 LRA members in numerous small groups scattered in CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Sudan. Of these 500, about half were combatants, including up to 200 Ugandans and 50 low-ranking fighters abducted primarily from ethnic Zande com- munities in CAR, DRC, and South Sudan. At least one LRA group, including Kony, was reportedly based near the Dafak Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) garrison in the disputed area of Kafia Kingi for over a year, until February or early March 2013.1 Reports of LRA presence in Kafia Kingi have been made since early 2010. A recent publication contained a detailed account of the history of LRA groups in the area complete with satellite imagery showing the location of a possible LRA camp at close proximity to a SAF garrison.2 In April 2013, Col. al Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ada, the official SAF spokesperson, told the Sudanese official news agency SUNA, ‘ the report [showing an alleged LRA camp in Kafia Kingi] is baseless and rejected,’ adding, ‘SAF has no interest in adopting or sheltering rebels from other countries.’3 But interviews with former LRA members who recently defected confirm that a large LRA group of over 100 people, including LRA leader Joseph Kony, spent about a year in Kafia Kingi. -

'When Will This End and What Will It Take?'

‘When will this end and what will it take?’ People’s perspectives on addressing the Lord’s Resistance Army conflict Logo using multiply on layers November 2011 Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately ‘ With all the armies of the world here, why isn’t Kony dead yet and the conflict over? When will this end and what will it take?’ Civil society leader, Democratic Republic of Congo CHAD SUDAN Birao Southern Darfur Kafia Kingi Sam-Ouandja Western Wau Zemongo Game Bahr-El-Ghazal CENTRAL Reserve AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC Haut-Mbomou Djemah Bria Western Equatoria Bambouti Ezo Obo Nzara Juba Zemio Yambio Bambari Mbomou Mboki Maridi Rafai Central Magwi Bangassou Bangui Banda Equatoria Bas-Uélé GARAMBA Yei Nimule Ango PARK Lake Doruma Kitgum Turkana Niangara Dungu Duru Arua Faradje Haut Uélé Gulu Lira Bunia Soroti LakeLake AlbertAlbert DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO UGANDA Kampala LRA area of operation after Operation Lightning Thunder LakeLake VictoriaVictoria end of 2008–11 LRA area of operation during the Juba talks 2006–08 RWANDA LRA area of operation during Operation Iron Fist 2002–05 0 150 300km BURUNDI TANZANIA © Conciliation Resources. This map is intended for illustrative purposes only. Borders, names and other features are presented according to common practice in the region. Conciliation Resources take no position on whether this representation is legally or politically valid. Disclaimer Acknowledgements This document has been produced with the Conciliation Resources is grateful to Frank financial assistance of the European Union van Acker who conducted the research and and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Uganda. contributed to the analysis in this report. -

Dominic Ongwen's Domino Effect

DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT HOW THE FALLOUT FROM A FORMER CHILD SOLDIER’S DEFECTION IS UNDERMINING JOSEPH KONY’S CONTROL OVER THE LRA JANUARY 2017 DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Map: Dominic Ongwen’s domino effect on the LRA I. Kony’s grip begins to loosen 4 Map: LRA combatants killed, 2012–2016 II. The fallout from the Ongwen saga 7 Photo: Achaye Doctor and Kidega Alala III. Achaye’s splinter group regroups and recruits in DRC 9 Photo: Children abducted by Achaye’s splinter group IV. A fractured LRA targets eastern CAR 11 Graph: Abductions by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 Map: Attacks by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 V. Encouraging defections from a fractured LRA 15 Graph: The decline of the LRA’s combatant force, 1999–2016 Conclusion 19 About The LRA Crisis Tracker & Contributors 20 LRA CRISIS TRACKER LRA CRISIS TRACKER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since founding the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda in the late 1980s, Joseph Kony’s control over the group’s command structure has been remarkably durable. Despite having no formal military training, he has motivated and ruled LRA members with a mixture of harsh discipline, incentives, and clever manipulation. When necessary, he has demoted or executed dozens of commanders that he perceived as threats to his power. Though Kony still commands the LRA, the weakening of his grip over the group’s command structure has been exposed by a dramatic series of events involving former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen. In late 2014, a group of Ugandan LRA officers, including Ongwen, began plotting to defect from the LRA. -

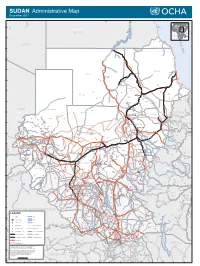

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

Estimated Age

The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. Since 2003, we have published the calendar in a daily planner format that provides our consumers with a variety of information related to international terrorism, including wanted terrorists; terrorist group fact sheets; technical issue related to terrorist tactics, techniques, and procedures; and potential dates of importance that terrorists might consider when planning attacks. The cover of this year’s CT Calendar highlights terrorists’ growing use of social media and other emerging online technologies to recruit, radicalize, and encourage adherents to carry out attacks. This year will be the last hardcopy publication of the calendar, as growing production costs necessitate our transition to more cost- effective dissemination methods. In the coming years, NCTC will use a variety of online and other media platforms to continue to share the valuable information found in the CT Calendar with a broad customer set, including our Federal, State, Local, and Tribal law enforcement partners; agencies across the Intelligence Community; private sector partners; and the US public. On behalf of NCTC, I want to thank all the consumers of the CT Calendar during the past 12 years. We hope you continue to find the CT Calendar beneficial to your daily efforts. Sincerely, Nicholas J. Rasmussen Director The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. This edition, like others since the Calendar was first published in daily planner format in 2003, contains many features across the full range of issues pertaining to international terrorism: terrorist groups, wanted terrorists, and technical pages on various threat-related topics. -

Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council

S/INF/68 Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council 1 August 2012 – 31 July 2013 Security Council Official Records United Nations New York, 2014 NOTE The present volume of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council contains the resolutions adopted and the decisions taken by the Council on substantive questions during the period from 1 August 2012 to 31 July 2013, as well as decisions on some of the more important procedural matters. The resolutions and decisions are set out in parts I and II, under general headings indicating the questions under consideration. In each part, the questions are arranged according to the date on which they were first taken up by the Council, and under each question the resolutions and decisions appear in chronological order. The resolutions are numbered in the order of their adoption. Each resolution is followed by the result of the vote. Decisions are usually taken without a vote. S/INF/68 ISSN 0257–1455 Contents Page Membership of the Security Council in 2012 and 2013 vii Resolutions adopted and decisions taken by the Security Council from 1 August 2012 to 31 July 2013 1 Part I. Questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security Items relating to the situation in the Middle East: A. The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question................................................................................. 1 B. The situation in the Middle East............................................................................................................................................ -

Race Against Time

Race Against Time The countdown to the referenda in Southern Sudan and Abyei By Aly Verjee October 2010 Published in 2010 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1DF, United Kingdom PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya RVI Executive Director: John Ryle RVI Programme Director: Christopher Kidner Editors: Colin Robertson and Aaron Griffiths Design: Emily Walmsley and Lindsay Nash Cover Image: Peter Martell / AFP / Getty Images ISBN 978-1-907431-03-6 Rights: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Race Against Time Page 1 of 65 Contents Author’s note and acknowledgments About the author The Rift Valley Institute SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS INTRODUCTION THE REFERENDUM IN SOUTHERN SUDAN AND THE REFERENDUM IN ABYEI 1. The legal timetable 2. Can the referenda be delayed? 3. Possible challenges to the results THE REFERENDUM IN SOUTHERN SUDAN 4. Legal conditions the Southern Sudan referendum needs to meet 5. Who can vote in the Southern Sudan referendum? 6. Do Blue Nile and South Kordofan affect the Southern Sudan referendum? 7. The ballot question in the Southern Sudan referendum 8. Is demarcation of the north-south boundary a precondition for the referendum? 9. Policy decisions required for the referendum voter registration process 10. Could voter registration be challenged? 11. Could Southern Sudan organize its own self-determination referendum? THE REFERENDUM IN ABYEI 12. Why the Abyei referendum matters 13. Who can vote in Abyei? 14. How does the Abyei referendum affect the Southern Sudan referendum? LESSONS FOR THE REFERENDA FROM THE 2010 ELECTIONS 15. The organization of the NEC and SSRC 16. -

REPORTS a Thematic Report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2010

NRC > SUDAN REPORT REPORTS A thematic report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2010 SOUTHERN SUDAN 2010: MITIGATING A HUMANITARIAN DISASTER NRC > SUDAN REPORT INTRODUCTION Following a comprehensive mapping exercise of existing scenario 1) First, a continued failure to resolve important issues relating reports on the fate of Southern Sudan and the Comprehensive to implementation of the CPA, including the census, electoral Peace Agreement (CPA) process, there appears to be a broad register, border demarcation and oil revenue agreement, is consensus that the humanitarian situation in Southern Sudan a recipe for disaster in Sudan. It certainly could lead to will deteriorate in 2010. armed conflict between the North and South and/or within the border states of Abyei, Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, This report seeks to acknowledge the negative impact a failed even though the CPA process itself is completed. CPA process would have on the humanitarian situation in Southern Sudan, while making the case that failing to address 2) Second, irrespective of progress with the CPA, there is an intra-South causes of conflict would render a successful urgent need to increase activities that focus on mitigating CPA process largely meaningless with regards to the current potential triggers for violence within Southern Sudan. This humanitarian situation in the South. includes election/referendum awareness education to combat Southerners’ limited access to information and therefore It is important to stress that although interrelated, the problems questionable understanding of the processes involved; associated with the CPA process and the causes of intra-South conflict resolution work in the areas worst affected by violence must be seen as two separate issues, for the purpose of inter-ethnic conflict over resource-use rights; and boosting effectively addressing both of them. -

2017 Trafficking in Persons Report

mobile phones, weapons, a martyr’s place in paradise, and the demonstrated serious and sustained efforts by conducting 134 “gift” of a wife upon joining the terrorist group. By forcibly trafficking investigations, including cases involving foreign recruiting and using children in combat and support roles, ISIS fishermen, and convicting 56 traffickers. Authorities identified has violated international humanitarian law and perpetrated 263 trafficking victims, provided access to shelter and other war crimes on a mass scale. Despite having signed a pledge of victim services, and enacted new regulations requiring standard commitment with an international organization in June 2014 to contracts and benefits for foreign fishermen hired overseas. demobilize all fighters younger than 18 years old, the Kurdish Although Taiwan authorities meet the minimum standards, People’s Protection Units (YPG) recruited and trained children in many cases judges sentenced traffickers to lenient penalties as young as 12 years old in 2016. An NGO reported in January not proportionate to the crimes, weakening deterrence and TAIWAN 2016 instances in which Iran forcibly recruited or coerced male undercutting efforts of police and prosecutors. Authorities Afghan refugees and migrants, including children, living in sometimes treated labor trafficking cases as labor disputes Iran to fight in Syria. In June 2016, the media reported Iran and did not convict any traffickers associated with exploiting recruited some Afghans inside Afghanistan to fight in Syria as foreign fishermen on Taiwan-flagged fishing vessels. well. Some foreigners, including migrants from Central Asia, are reportedly forced, coerced, or fraudulently recruited to join extremist fighters, including ISIS. The Syrian refugee population is highly vulnerable to trafficking in neighboring countries, particularly Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey. -

South Sudan Giraffe Conservation Status Report September 2020

Country Profile Republic of South Sudan Giraffe Conservation Status Report September 2020 N.B. Although the focus of this profile is on the Republic of South Sudan, reference is made to the historical occurrence of giraffe in the historical Sudan. General statistics Size of country: 644,329 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 11.1% Species and subspecies In 2016 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) completed the first detailed assessment of the conservation status of giraffe, revealing that their numbers are in peril. This was further emphasised when the majority of the IUCN recognised subspecies where assessed in 2018 – some as Critically Endangered. While this update further confirms the real threat to one of Africa’s most charismatic megafauna, it also highlights a rather confusing aspect of giraffe conservation: how many species/subspecies of giraffe are there? The IUCN currently recognises one species (Giraffa camelopardalis) and nine subspecies of giraffe (Muller et al. 2018) historically based on outdated assessments of their morphological features and geographic ranges. The subspecies are thus divided: Angolan giraffe (G. c. angolensis), Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum), Masai giraffe (G. c. tippleskirchi), Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis), reticulated giraffe (G. c. reticulata), Rothschild’s giraffe (G. c. rothschildi), South African giraffe (G. c. giraffa), Thornicroft’s giraffe (G. c. thornicrofti) and West African giraffe (G. c. peralta). However, over the past decade GCF together with their partner Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (BiK-F) have performed the first-ever comprehensive DNA sampling and analysis (genomic, nuclear and mitochondrial) from all major natural populations of giraffe throughout their range in Africa. -

Sudan's Harboring of the LRA in the Kafia Kingi Enclave, 2009-2013

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT Sudan’s Harboring of the LRA in the Kafia Kingi Enclave, 2009-2013 © DigitalGlobe 2013 WRITTEN BY CO-PRODUCED BY HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT Sudan’s Harboring of the LRA in the Kafia Kingi Enclave, 2009-2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Methodology ........................................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary and Recommendations ....................................................................................4 [Map and Timeline] The LRA’s Long Road to Kafia Kingi ..............................................................7 I. The LRA’s Historic Alliance with Sudan .........................................................................................9 II. LRA Activity in and near Kafia Kingi ...........................................................................................13 [Feature] Disputed Territory: The Status of the Kafia Kingi Enclave ............................................16 III. Toward a Productive Role for Sudan ..........................................................................................20 Appendix A: Map and Detailed Timeline of LRA Activity in and around Kafia Kingi ...........................24 Appendix B: Satellite Imagery of Likely LRA Encampments in Kafia Kingi........................................28 Cover Image: Satellite imagery from December 2012, commissioned by Amnesty International USA and provided by DigitalGlobe, shows likely LRA camps within the Kafia Kingi enclave. © DigitalGlobe