'When Will This End and What Will It Take?'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The LRA in Kafia Kingi

The LRA in Kafia Kingi The suspension of the Ugandan army operation in the Central African Republic (CAR) following the overthrow of the CAR regime in March 2013 may have given some respite to the LRA, which by the first quarter of 2013 appeared to be at its weakest in its long history. As of May 2013, there were some 500 LRA members in numerous small groups scattered in CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Sudan. Of these 500, about half were combatants, including up to 200 Ugandans and 50 low-ranking fighters abducted primarily from ethnic Zande com- munities in CAR, DRC, and South Sudan. At least one LRA group, including Kony, was reportedly based near the Dafak Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) garrison in the disputed area of Kafia Kingi for over a year, until February or early March 2013.1 Reports of LRA presence in Kafia Kingi have been made since early 2010. A recent publication contained a detailed account of the history of LRA groups in the area complete with satellite imagery showing the location of a possible LRA camp at close proximity to a SAF garrison.2 In April 2013, Col. al Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ada, the official SAF spokesperson, told the Sudanese official news agency SUNA, ‘ the report [showing an alleged LRA camp in Kafia Kingi] is baseless and rejected,’ adding, ‘SAF has no interest in adopting or sheltering rebels from other countries.’3 But interviews with former LRA members who recently defected confirm that a large LRA group of over 100 people, including LRA leader Joseph Kony, spent about a year in Kafia Kingi. -

WAR and PROTECTED AREAS AREAS and PROTECTED WAR Vol 14 No 1 Vol 14 Protected Areas Programme Areas Protected

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Parks Protected Areas Programme © 2004 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial JEFFREY A. MCNEELY 1 Parks in the crossfire: strategies for effective conservation in areas of armed conflict JUDY OGLETHORPE, JAMES SHAMBAUGH AND REBECCA KORMOS 2 Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage 2004 Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo GUY DEBONNET AND KES HILLMAN-SMITH 9 Status of the Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire and the effects of war FRAUKE FISCHER 17 Recovering from conflict: the case of Dinder and other national parks in Sudan WOUTER VAN HOVEN AND MUTASIM BASHIR NIMIR 26 Threats to Nepal’s protected areas PRALAD YONZON 35 Tayrona National Park, Colombia: international support for conflict resolution through tourism JENS BRÜGGEMANN AND EDGAR EMILIO RODRÍGUEZ 40 Establishing a transboundary peace park in the demilitarized zone on the Kuwaiti/Iraqi borders FOZIA ALSDIRAWI AND MUNA FARAJ 48 Résumés/Resumenes 56 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme, in 2004 these are: Vol 14 No 1: War and protected areas Vol 14 No 2: Durban World Parks Congress Vol 14 No 3: Global change and protected areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation and ecologically The international journal for protected area managers sustainable development ISSN: 0960-233X Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN – Subscribing to Parks The World Conservation Union. -

Investigation of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Wild and Domestic Animals in Radom National Park; South Darfur State , Sudan

Investigation of gastrointestinal parasites in wild and domestic animals in Radom National Park; South Darfur State , Sudan . Abuessailla, A. A. 1; Ismail, A. A. 2 and Agab , H. M. 3 1- Ministry of Animals Resources and Fisheries, South Darfur State. E.mail: [email protected]. 2- Department of Pathology, Parasitology and Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Sudan University of Science and Technology. 3- Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Science, College of Animal Production Technology, Sudan University of Science and Technology. ABSTRACT: This paper describes the results of a survey of the gastrointestinal helminth parasites in the faecal matters of fourteen wildlife species and four domestic animal species collected from five sites in Radom National Park (R.N.P), South Darfour State, Sudan, namely: Radom area, Alhufra, Titrbi, Kafindibei and Kafiakingi. Out of the 1179 faecal samples examined 244 (20.7%) contained eggs of helminth parasites. Donkeys had the highest overall infection rate of helminth eggs (47.9%), while Phacochoerus aethiopicus (warthog ) showed the lowest prevalence (2.7%). Prevalence of the parasites was highest (30.2%) in domestic animals and lowest (10.9%) in the wild ones. Kafindibei area showed the highest prevalence of 25.3%, followed by Radom area with a prevalence of 20.5%. Alhufra area showed the lowest prevalence (18.6%). The main prevalent helminth parasites were Trichostrongylus ( 13.5%) and Strongyloides (7.3%). KEY WORDS: Internal parasites, wild life, domestic animals, radom, south darfur . lumbricoides in the wild pig; Strongyloid INTRODUCTION spp ., in the gazelle; Ascaris pythonis in The available information on parasitic infection among wildlife species, the python and Toxascaris leonina in the particularly in the Sudan, is scanty as only Panthera leo (lion). -

Dominic Ongwen's Domino Effect

DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT HOW THE FALLOUT FROM A FORMER CHILD SOLDIER’S DEFECTION IS UNDERMINING JOSEPH KONY’S CONTROL OVER THE LRA JANUARY 2017 DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Map: Dominic Ongwen’s domino effect on the LRA I. Kony’s grip begins to loosen 4 Map: LRA combatants killed, 2012–2016 II. The fallout from the Ongwen saga 7 Photo: Achaye Doctor and Kidega Alala III. Achaye’s splinter group regroups and recruits in DRC 9 Photo: Children abducted by Achaye’s splinter group IV. A fractured LRA targets eastern CAR 11 Graph: Abductions by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 Map: Attacks by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 V. Encouraging defections from a fractured LRA 15 Graph: The decline of the LRA’s combatant force, 1999–2016 Conclusion 19 About The LRA Crisis Tracker & Contributors 20 LRA CRISIS TRACKER LRA CRISIS TRACKER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since founding the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda in the late 1980s, Joseph Kony’s control over the group’s command structure has been remarkably durable. Despite having no formal military training, he has motivated and ruled LRA members with a mixture of harsh discipline, incentives, and clever manipulation. When necessary, he has demoted or executed dozens of commanders that he perceived as threats to his power. Though Kony still commands the LRA, the weakening of his grip over the group’s command structure has been exposed by a dramatic series of events involving former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen. In late 2014, a group of Ugandan LRA officers, including Ongwen, began plotting to defect from the LRA. -

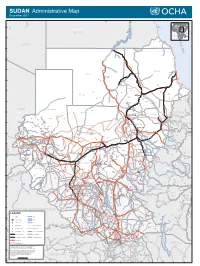

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

Estimated Age

The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. Since 2003, we have published the calendar in a daily planner format that provides our consumers with a variety of information related to international terrorism, including wanted terrorists; terrorist group fact sheets; technical issue related to terrorist tactics, techniques, and procedures; and potential dates of importance that terrorists might consider when planning attacks. The cover of this year’s CT Calendar highlights terrorists’ growing use of social media and other emerging online technologies to recruit, radicalize, and encourage adherents to carry out attacks. This year will be the last hardcopy publication of the calendar, as growing production costs necessitate our transition to more cost- effective dissemination methods. In the coming years, NCTC will use a variety of online and other media platforms to continue to share the valuable information found in the CT Calendar with a broad customer set, including our Federal, State, Local, and Tribal law enforcement partners; agencies across the Intelligence Community; private sector partners; and the US public. On behalf of NCTC, I want to thank all the consumers of the CT Calendar during the past 12 years. We hope you continue to find the CT Calendar beneficial to your daily efforts. Sincerely, Nicholas J. Rasmussen Director The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. This edition, like others since the Calendar was first published in daily planner format in 2003, contains many features across the full range of issues pertaining to international terrorism: terrorist groups, wanted terrorists, and technical pages on various threat-related topics. -

Environmental Assessment of the Sudan

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SUDAN LOCUST CONTROL PROJECT 650 - 0087 United States Agency for International Development Mission to Sudan Khartoum, Sudan August, 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBR3EVIATIONS SECTION 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Purpose of Assessment 2.1 AID Environmental Procedures 2.2 Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Locust Control 2.3 Environmental and Pesticide Legislation/Sudan 3.0 Scoping Procedure 4.0 Proposed Action and Alternatives 4.1 Elack.ground 4.2 Project Goals, Purpose and Output 4.3 Other Donor Activities 4.4 Analysis of Alternatives 4.4.1 Economical 4.4.2 Political 4.4.3 Environmental 5.0 Environment to be Affected by Action 5.1 Human Population 5.2 Farks. Reserves and Sanctuaries 5.3 Rare, Endangered and Migratory Species 5.4 Agricultural Resources 5.4.1 Mechanized Rainfed Sector 5.4.2 Rainfed Traditional Sector 5.4.3 Pastoralists 6.0 Environmental Assessment of Action 6.1 Selection of Insecticides for Locust/Grasshopper Control 6.1.1 USEPA Registration Status of Selected Insecticides and Recommendations of the L/G PEA 6.1.2 Field Testing of Selected Insecticides 6.1.3 Selection of Pesticides for Sudan Program 2 6.3 Application Methods and Equipment 6.3.1 Aerial 6.3.2 Ground C.14 Acute and Long Term Environmental Tox.icological Hazards 6.5 Efficacy of Selected Insecticides for L/G Control 6.6 Effect of Selected Insecticides on Non- Target Organisms and the Natural Environm 6.7 Conditions Under Which Insecticides are to Used 6.8 Availability and Effectiveness -

Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council

S/INF/68 Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council 1 August 2012 – 31 July 2013 Security Council Official Records United Nations New York, 2014 NOTE The present volume of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council contains the resolutions adopted and the decisions taken by the Council on substantive questions during the period from 1 August 2012 to 31 July 2013, as well as decisions on some of the more important procedural matters. The resolutions and decisions are set out in parts I and II, under general headings indicating the questions under consideration. In each part, the questions are arranged according to the date on which they were first taken up by the Council, and under each question the resolutions and decisions appear in chronological order. The resolutions are numbered in the order of their adoption. Each resolution is followed by the result of the vote. Decisions are usually taken without a vote. S/INF/68 ISSN 0257–1455 Contents Page Membership of the Security Council in 2012 and 2013 vii Resolutions adopted and decisions taken by the Security Council from 1 August 2012 to 31 July 2013 1 Part I. Questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security Items relating to the situation in the Middle East: A. The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question................................................................................. 1 B. The situation in the Middle East............................................................................................................................................ -

Cop18 Prop. 19

Original language: English CoP18 Prop. 19 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Colombo (Sri Lanka), 23 May – 3 June 2019 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Transfer from Appendix II to Appendix I of Balearica pavonina in accordance with Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16), Annex 1. Paragraph C) i): A marked decline in the population size in the wild has been observed as ongoing. Paragraph C) ii): A marked decline in the population size in the wild which has been inferred or projected on the basis of levels or patterns of exploitation and a decrease in area of habitat. B. Proponent Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal*: C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Aves 1.2 Order: Gruiformes 1.3 Family: Gruidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Balearica pavonina (Linnaeus, 1758) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: Subspecies B. p. pavonina and B. p. ceciliae. 1.6 Common names: English: Black-crowned Crane, West African Crowned Crane French: Grue couronnée de l’Afrique de l’ouest et du Soudan, Grue couronnée Spanish: Grulla coronada del África occidental, Grulla coronada cuellinegra, Grulla coronada 1.7 Code numbers: 2. Overview In 2010, Balearica pavonina was reclassified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red-list of Threatened Species. This classification was reaffirmed in 2012 and 2016 on the basis that “recent surveys have shown a rapid * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Race Against Time

Race Against Time The countdown to the referenda in Southern Sudan and Abyei By Aly Verjee October 2010 Published in 2010 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1DF, United Kingdom PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya RVI Executive Director: John Ryle RVI Programme Director: Christopher Kidner Editors: Colin Robertson and Aaron Griffiths Design: Emily Walmsley and Lindsay Nash Cover Image: Peter Martell / AFP / Getty Images ISBN 978-1-907431-03-6 Rights: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Race Against Time Page 1 of 65 Contents Author’s note and acknowledgments About the author The Rift Valley Institute SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS INTRODUCTION THE REFERENDUM IN SOUTHERN SUDAN AND THE REFERENDUM IN ABYEI 1. The legal timetable 2. Can the referenda be delayed? 3. Possible challenges to the results THE REFERENDUM IN SOUTHERN SUDAN 4. Legal conditions the Southern Sudan referendum needs to meet 5. Who can vote in the Southern Sudan referendum? 6. Do Blue Nile and South Kordofan affect the Southern Sudan referendum? 7. The ballot question in the Southern Sudan referendum 8. Is demarcation of the north-south boundary a precondition for the referendum? 9. Policy decisions required for the referendum voter registration process 10. Could voter registration be challenged? 11. Could Southern Sudan organize its own self-determination referendum? THE REFERENDUM IN ABYEI 12. Why the Abyei referendum matters 13. Who can vote in Abyei? 14. How does the Abyei referendum affect the Southern Sudan referendum? LESSONS FOR THE REFERENDA FROM THE 2010 ELECTIONS 15. The organization of the NEC and SSRC 16. -

REPORTS a Thematic Report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2010

NRC > SUDAN REPORT REPORTS A thematic report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2010 SOUTHERN SUDAN 2010: MITIGATING A HUMANITARIAN DISASTER NRC > SUDAN REPORT INTRODUCTION Following a comprehensive mapping exercise of existing scenario 1) First, a continued failure to resolve important issues relating reports on the fate of Southern Sudan and the Comprehensive to implementation of the CPA, including the census, electoral Peace Agreement (CPA) process, there appears to be a broad register, border demarcation and oil revenue agreement, is consensus that the humanitarian situation in Southern Sudan a recipe for disaster in Sudan. It certainly could lead to will deteriorate in 2010. armed conflict between the North and South and/or within the border states of Abyei, Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, This report seeks to acknowledge the negative impact a failed even though the CPA process itself is completed. CPA process would have on the humanitarian situation in Southern Sudan, while making the case that failing to address 2) Second, irrespective of progress with the CPA, there is an intra-South causes of conflict would render a successful urgent need to increase activities that focus on mitigating CPA process largely meaningless with regards to the current potential triggers for violence within Southern Sudan. This humanitarian situation in the South. includes election/referendum awareness education to combat Southerners’ limited access to information and therefore It is important to stress that although interrelated, the problems questionable understanding of the processes involved; associated with the CPA process and the causes of intra-South conflict resolution work in the areas worst affected by violence must be seen as two separate issues, for the purpose of inter-ethnic conflict over resource-use rights; and boosting effectively addressing both of them.