South Sudan Giraffe Conservation Status Report September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The LRA in Kafia Kingi

The LRA in Kafia Kingi The suspension of the Ugandan army operation in the Central African Republic (CAR) following the overthrow of the CAR regime in March 2013 may have given some respite to the LRA, which by the first quarter of 2013 appeared to be at its weakest in its long history. As of May 2013, there were some 500 LRA members in numerous small groups scattered in CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Sudan. Of these 500, about half were combatants, including up to 200 Ugandans and 50 low-ranking fighters abducted primarily from ethnic Zande com- munities in CAR, DRC, and South Sudan. At least one LRA group, including Kony, was reportedly based near the Dafak Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) garrison in the disputed area of Kafia Kingi for over a year, until February or early March 2013.1 Reports of LRA presence in Kafia Kingi have been made since early 2010. A recent publication contained a detailed account of the history of LRA groups in the area complete with satellite imagery showing the location of a possible LRA camp at close proximity to a SAF garrison.2 In April 2013, Col. al Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ada, the official SAF spokesperson, told the Sudanese official news agency SUNA, ‘ the report [showing an alleged LRA camp in Kafia Kingi] is baseless and rejected,’ adding, ‘SAF has no interest in adopting or sheltering rebels from other countries.’3 But interviews with former LRA members who recently defected confirm that a large LRA group of over 100 people, including LRA leader Joseph Kony, spent about a year in Kafia Kingi. -

The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan: an Evolutionary Approach to Environment and Development

The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan: An Evolutionary Approach to Environment and Development JOHN GOWDY HANNES LANG Professor of Economics and Professor of Science Research Associate & Technology Studies School of Life Sciences Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Technical University Munich Troy New York, 12180 USA 85354 Freising, Germany [email protected] [email protected] The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan 1 Contents About the Authors ....................................................................................................................2 Key Findings of this Report .......................................................................................................3 I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 II. The Sudd ............................................................................................................................ 8 III. Human Presence in the Sudd ..............................................................................................10 IV. Development Threats to the Sudd ........................................................................................ 11 V. Value Transfer as a Framework for Developing the Sudd Wetland ......................................... 15 VI. Maintaining the Ecosystem Services of the Sudd: An Evolutionary Approach to Development and the Environment ...........................................26 -

'When Will This End and What Will It Take?'

‘When will this end and what will it take?’ People’s perspectives on addressing the Lord’s Resistance Army conflict Logo using multiply on layers November 2011 Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately ‘ With all the armies of the world here, why isn’t Kony dead yet and the conflict over? When will this end and what will it take?’ Civil society leader, Democratic Republic of Congo CHAD SUDAN Birao Southern Darfur Kafia Kingi Sam-Ouandja Western Wau Zemongo Game Bahr-El-Ghazal CENTRAL Reserve AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC Haut-Mbomou Djemah Bria Western Equatoria Bambouti Ezo Obo Nzara Juba Zemio Yambio Bambari Mbomou Mboki Maridi Rafai Central Magwi Bangassou Bangui Banda Equatoria Bas-Uélé GARAMBA Yei Nimule Ango PARK Lake Doruma Kitgum Turkana Niangara Dungu Duru Arua Faradje Haut Uélé Gulu Lira Bunia Soroti LakeLake AlbertAlbert DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO UGANDA Kampala LRA area of operation after Operation Lightning Thunder LakeLake VictoriaVictoria end of 2008–11 LRA area of operation during the Juba talks 2006–08 RWANDA LRA area of operation during Operation Iron Fist 2002–05 0 150 300km BURUNDI TANZANIA © Conciliation Resources. This map is intended for illustrative purposes only. Borders, names and other features are presented according to common practice in the region. Conciliation Resources take no position on whether this representation is legally or politically valid. Disclaimer Acknowledgements This document has been produced with the Conciliation Resources is grateful to Frank financial assistance of the European Union van Acker who conducted the research and and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Uganda. contributed to the analysis in this report. -

WAR and PROTECTED AREAS AREAS and PROTECTED WAR Vol 14 No 1 Vol 14 Protected Areas Programme Areas Protected

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Parks Protected Areas Programme © 2004 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial JEFFREY A. MCNEELY 1 Parks in the crossfire: strategies for effective conservation in areas of armed conflict JUDY OGLETHORPE, JAMES SHAMBAUGH AND REBECCA KORMOS 2 Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage 2004 Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo GUY DEBONNET AND KES HILLMAN-SMITH 9 Status of the Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire and the effects of war FRAUKE FISCHER 17 Recovering from conflict: the case of Dinder and other national parks in Sudan WOUTER VAN HOVEN AND MUTASIM BASHIR NIMIR 26 Threats to Nepal’s protected areas PRALAD YONZON 35 Tayrona National Park, Colombia: international support for conflict resolution through tourism JENS BRÜGGEMANN AND EDGAR EMILIO RODRÍGUEZ 40 Establishing a transboundary peace park in the demilitarized zone on the Kuwaiti/Iraqi borders FOZIA ALSDIRAWI AND MUNA FARAJ 48 Résumés/Resumenes 56 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme, in 2004 these are: Vol 14 No 1: War and protected areas Vol 14 No 2: Durban World Parks Congress Vol 14 No 3: Global change and protected areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation and ecologically The international journal for protected area managers sustainable development ISSN: 0960-233X Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN – Subscribing to Parks The World Conservation Union. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

Dominic Ongwen's Domino Effect

DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT HOW THE FALLOUT FROM A FORMER CHILD SOLDIER’S DEFECTION IS UNDERMINING JOSEPH KONY’S CONTROL OVER THE LRA JANUARY 2017 DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Map: Dominic Ongwen’s domino effect on the LRA I. Kony’s grip begins to loosen 4 Map: LRA combatants killed, 2012–2016 II. The fallout from the Ongwen saga 7 Photo: Achaye Doctor and Kidega Alala III. Achaye’s splinter group regroups and recruits in DRC 9 Photo: Children abducted by Achaye’s splinter group IV. A fractured LRA targets eastern CAR 11 Graph: Abductions by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 Map: Attacks by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 V. Encouraging defections from a fractured LRA 15 Graph: The decline of the LRA’s combatant force, 1999–2016 Conclusion 19 About The LRA Crisis Tracker & Contributors 20 LRA CRISIS TRACKER LRA CRISIS TRACKER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since founding the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda in the late 1980s, Joseph Kony’s control over the group’s command structure has been remarkably durable. Despite having no formal military training, he has motivated and ruled LRA members with a mixture of harsh discipline, incentives, and clever manipulation. When necessary, he has demoted or executed dozens of commanders that he perceived as threats to his power. Though Kony still commands the LRA, the weakening of his grip over the group’s command structure has been exposed by a dramatic series of events involving former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen. In late 2014, a group of Ugandan LRA officers, including Ongwen, began plotting to defect from the LRA. -

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 OCTOBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Evaluation Team, which comprised: Leo Bill Emerson (team leader), Alex B. Muhweezi (biodiversity expert) and James Thubo Ayul Ph.D. (livelihoods expert). END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 Contracted under 607300.01.060 Monitoring and Evaluation Support Project DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. (THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK) ABSTRACT This is an end-of-program performance evaluation report for the Boma-Jonglei-Equatoria Landscape (BJEL) program covering the 2008-2017 whose purpose is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and impact of the BJEL program. The results of the evaluation will inform future programming of similar project activities by USAID/South Sudan, the implementing partner Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) entities and other donor organizations. The evaluation utilized a mixed-method approach, relying on quantitative and qualitative data from both primary and secondary sources, based on a set of indicators. The Evaluation interrogated information obtained and provided responses to the following five evaluation questions. a. How effective was the BJEL program in achieving project objectives? b. Did the project achieve the right focus and balance in terms of design, theory of change/development hypothesis, and strengthening strategies for sustainable safeguards of the wildlife population needs of South Sudan? c. -

South Sudan Vehicle Workshop Hazardous Waste Management

Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering 5 (2017) 157-169 doi: 10.17265/2328-2142/2017.03.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING South Sudan Vehicle Workshop Hazardous Waste Management Zoran Chachorovski, Drasko Atanasoski, Micho Apostolov and Aneta Stojanovska-Stefanova Faculty of Tourism and Business Logistics, University Goce Delcev, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia Abstract: All facility managers and fleet managers know how difficult it can be to effectively manage hazardous wastes and identify economic recycling opportunities. This report reviews the context surrounding GO’s (global organization) vehicle workshops and environmental management in South Sudan, specifically relating to hazardous waste management. Potential recycling opportunities are identified and some preliminary suggestions for hazardous waste management are made. Key words: Environment, legislation, policy, management, government, private sector. 1. Introduction Testing of used oil, filtration and processing in a centrifuge to prolong the life of the oil; The environmental sustainability (facilities Substitution of non-chlorinated brake parts management) office and global fleet have teamed up to cleaner for chlorinated cleaners to reduce pollution; help find ways to save money and keep the Possible use of biodegradable lubricants; environment clean with good management of Cleaning of coolant fluids using ion exchange hazardous wastes from vehicle maintenance technology; workshops. Hazardous waste includes batteries, tyres, Solvent distillation to allow recovery and -

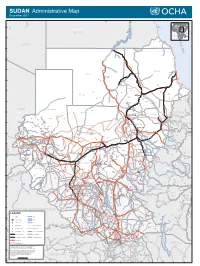

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

South Sudan Climate Vulnerability Profile: Sector- and Location-Specific Climate Risks and Resilience Recommendations

PHOTO CREDIT: USAID|SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CLIMATE VULNERABILITY PROFILE: SECTOR- AND LOCATION-SPECIFIC CLIMATE RISKS AND RESILIENCE RECOMMENDATIONS MAY 2019 This document was prepared for USAID/South Sudan by The Cadmus Group LLC under USAID’s Global Environmental Management Support Program, Contract Number GS-10F-0105J. Authors: Colin Quinn, Ashley Fox, Kye Baroang, Dan Evans, Melq Gomes, and Josh Habib The Cadmus Group, LLC The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................................. 2 HISTORICAL AND FUTURE CLIMATE CHANGE IN SOUTH SUDAN ...................................................................... 2 AGRICULTURE VULNERABILITY AND RESILIENCE ........................................................................................................ 3 CLIMATE CHANGE, MIGRATION AND CONFLICT ....................................................................................................... 5 THE VULNERABILITY OF THE SUDD WETLAND ............................................................................................................ 6 POTENTIAL AREAS OF INVESTMENT TO IMPROVE CLIMATE RESILIENCE ..........................................................