Study on the Interaction Between Security and Wildlife Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Management Models in Africa

Collaborative Management Models in Africa Peter Lindsey Mujon Baghai Introduction to the context behind the development of and rationale for CMPs in Africa Africa’s PAs represent potentially priceless assets due to the environmental services they provide and for their potential economic value via tourism However, the resources allocated for management of PAs are far below what is needed in most countries to unlock their potential A study in progress indicates that of 22 countries assessed, half have average PA management budgets of <10% of what is needed for effective management (Lindsey et al. in prep) This means that many countries will lose their wildlife assets before ever really being able to benefit from them So why is there such under-investment? Two big reasons - a) competing needs and overall budget shortages; b) a high burden of PAs relative to wealth However, in some cases underinvestment may be due to: ● Misconceptions that PAs can pay for themselves on a park level ● Lack of appreciation among policy makers that PAs need investment to yield economic dividends This mistake has grave consequences… This means that in most countries, PA networks are not close to delivering their potential: • Economic value • Social value • Ecological value Africa’s PAs are under growing pressure from an array of threats Ed Sayer ProtectedInsights areas fromare becoming recent rapidly research depleted in many areas There is a case for elevated support for Africa’s PA network from African governments But also a case for greater investment from -

The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan: an Evolutionary Approach to Environment and Development

The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan: An Evolutionary Approach to Environment and Development JOHN GOWDY HANNES LANG Professor of Economics and Professor of Science Research Associate & Technology Studies School of Life Sciences Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Technical University Munich Troy New York, 12180 USA 85354 Freising, Germany [email protected] [email protected] The Economic, Cultural and Ecosystem Values of the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan 1 Contents About the Authors ....................................................................................................................2 Key Findings of this Report .......................................................................................................3 I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 II. The Sudd ............................................................................................................................ 8 III. Human Presence in the Sudd ..............................................................................................10 IV. Development Threats to the Sudd ........................................................................................ 11 V. Value Transfer as a Framework for Developing the Sudd Wetland ......................................... 15 VI. Maintaining the Ecosystem Services of the Sudd: An Evolutionary Approach to Development and the Environment ...........................................26 -

2019 LRF Progress Report

February 2019 Progress Report LION RECOVERY FUND ©Frans Lanting/lanting.com Roaring Forward SINCE AUGUST 2018: $1.58 Million granted CLAWS Conservancy, Conservation Lower Zambezi, Honeyguide, Ian Games (independent consultant), Kenya Wildlife Trust, Lilongwe Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC frica’s lion population has declined by approximately half South Africa, WildAid, Zambezi Society, Zambian Carnivore Programme/Conservation South Luangwa A during the last 25 years. The Lion Recovery Fund (LRF) was created to support the best efforts to stop this decline 4 New countries covered by LRF grants and recover the lions we have lost. The LRF—an initiative of Botswana, Chad, Gabon, Kenya the Wildlife Conservation Network in partnership with the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation—entered its second year with a strategic vision to bolster and expand lion conservation LRF IMPACT TO DATE: across the continent. 42 Projects Though the situation varies from country to country, in a number of regions we are starting to see signs of hope, thanks 18 Countries to the impressive conservation work of our partners in the 29 Partners field. Whether larger organizations or ambitious individuals, our partners are addressing threats facing lions throughout $4 Million deployed Africa. This report presents the progress they made from August 2018 through January 2019. 23% of Africa’s lion range covered by LRF grantees Lions can recover. 30% of Africa’s lion population covered There is strong political will for conservation in Africa. Many by LRF grantees African governments are making conservation a priority 20,212 Snares removed and there are already vast areas of land set aside for wildlife throughout the continent. -

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa's Sudano-Sahel

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa’s Sudano-Sahel The interface of conservation, security, and development Mbororo pastoralists illegally grazing cattle in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Naftali Honig/African Parks Africa’s Sudano-Sahel is a distinct bioclimatic and ecological zone made up of savanna and savanna-forest transition Program Priorities habitat that covers approximately 7.7 million square kilometers of the continent. Rich in species diversity, the • Increased data gathering and assessment of core Sudano-Sahel region represents one of the last remaining natural resource assets across the Sudano-Sahel region. intact wilderness areas in the world, and is a high priority • Efficient data-sharing, analysis, and dissemination for wildlife conservation. It is home to an array of antelope between relevant stakeholders spanning conservation, species such as giant eland and greater kudu, in addition to security, and development sectors, and in collaboration African wild dog, Kordofan giraffe, African elephant, African with rural agriculturalists and pastoralists. lion, leopard, and giant pangolin. • Enhancement and promotion of multi-level This region is also home to many rural communities who rely governance approaches to resolve conflict and stabilize on the landscape’s natural resources, including pastoralists, transhumance corridors. whose livelihoods and cultural identity are centered around • Continuation and expansion of strategic investments in strategic mobility to access seasonally available grazing the network of priority protected areas and their buffer resources and water. Instability, climate change, and zones across the Sudano-Sahel, in order to improve increasing pressures from unsustainable land use activities security for both wildlife and surrounding communities. -

WAR and PROTECTED AREAS AREAS and PROTECTED WAR Vol 14 No 1 Vol 14 Protected Areas Programme Areas Protected

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Parks Protected Areas Programme © 2004 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial JEFFREY A. MCNEELY 1 Parks in the crossfire: strategies for effective conservation in areas of armed conflict JUDY OGLETHORPE, JAMES SHAMBAUGH AND REBECCA KORMOS 2 Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage 2004 Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo GUY DEBONNET AND KES HILLMAN-SMITH 9 Status of the Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire and the effects of war FRAUKE FISCHER 17 Recovering from conflict: the case of Dinder and other national parks in Sudan WOUTER VAN HOVEN AND MUTASIM BASHIR NIMIR 26 Threats to Nepal’s protected areas PRALAD YONZON 35 Tayrona National Park, Colombia: international support for conflict resolution through tourism JENS BRÜGGEMANN AND EDGAR EMILIO RODRÍGUEZ 40 Establishing a transboundary peace park in the demilitarized zone on the Kuwaiti/Iraqi borders FOZIA ALSDIRAWI AND MUNA FARAJ 48 Résumés/Resumenes 56 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme, in 2004 these are: Vol 14 No 1: War and protected areas Vol 14 No 2: Durban World Parks Congress Vol 14 No 3: Global change and protected areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation and ecologically The international journal for protected area managers sustainable development ISSN: 0960-233X Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN – Subscribing to Parks The World Conservation Union. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

SES Scientific Explorer Annual Review 2020.Pdf

SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER Dr Jane Goodall, Annual Review 2020 SES Lifetime Achievement 2020 (photo by Vincent Calmel) Welcome Scientific Exploration Society (SES) is a UK-based charity (No 267410) that was founded in 1969 by Colonel John Blashford-Snell and colleagues. It is the longest-running scientific exploration organisation in the world. Each year through its Explorer Awards programme, SES provides grants to individuals leading scientific expeditions that focus on discovery, research, and conservation in remote parts of the world, offering knowledge, education, and community aid. Members and friends enjoy charity events and regular Explorer Talks, and are also given opportunities to join exciting scientific expeditions. SES has an excellent Honorary Advisory Board consisting of famous explorers and naturalists including Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Dr Jane Goodall, Rosie Stancer, Pen Hadow, Bear Grylls, Mark Beaumont, Tim Peake, Steve Backshall, Vanessa O’Brien, and Levison Wood. Without its support, and that of its generous benefactors, members, trustees, volunteers, and part-time staff, SES would not achieve all that it does. DISCOVER RESEARCH CONSERVE Contents 2 Diary 2021 19 Vanessa O’Brien – Challenger Deep 4 Message from the Chairman 20 Books, Books, Books 5 Flying the Flag 22 News from our Community 6 Explorer Award Winners 2020 25 Support SES 8 Honorary Award Winners 2020 26 Obituaries 9 ‘Oscars of Exploration’ 2020 30 Medicine Chest Presentation Evening LIVE broadcast 32 Accounts and Notice of 2021 AGM 10 News from our Explorers 33 Charity Information 16 Top Tips from our Explorers “I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward.” Mark Beaumont, SES Lifetime Achievement 2018 and David Livingstone SES Honorary Advisory Board member (photo by Ben Walton) SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER > 2020 Magazine 1 Please visit SES on EVENTBRITE for full details and tickets to ALL our events. -

Waging a War to Save Biodiversity: the Rise of Militarized Conservation

Waging a war to save biodiversity: the rise of militarized conservation ROSALEEN DUFFY* Conserving biodiversity is a central environmental concern, and conservationists increasingly talk in terms of a ‘war’ to save species. International campaigns present a specific image: that parks agencies and conservation NGOs are engaged in a continual battle to protect wildlife from armies of highly organized criminal poach- ers who are financially motivated. The war to save biodiversity is presented as a legitimate war to save critically endangered species such as rhinos, tigers, gorillas and elephants. This is a significant shift in approach since the late 1990s, when community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) and participatory techniques were at their peak. Since the early 2000s there has been a re-evaluation of a renewed interest in fortress conservation models to protect wildlife, including by military means.1 Yet, as Lunstrum notes, there is a dearth of research on ‘green militarization’, a process by which military approaches and values are increasingly embedded in conservation practice.2 This article examines the dangers of a ‘war for biodiversity’: notably that it is used to justify highly repressive and coercive policies.3 Militarized forms of anti- poaching are increasingly justified by conservation NGOs keen to protect wildlife; these issues are even more important as conservationists turn to private military companies to guard and enforce protected areas. This article first examines concep- tual debates around the war for biodiversity; second, it offers an analysis of current trends in militarized forms of anti-poaching; third, it offers a critical reflection on such approaches via an examination of the historical, economic, social and political creation of poaching as a mode of illegal behaviour; and finally, it traces how a militarized approach to anti-poaching developed out of the production of poaching as a category. -

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 OCTOBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Evaluation Team, which comprised: Leo Bill Emerson (team leader), Alex B. Muhweezi (biodiversity expert) and James Thubo Ayul Ph.D. (livelihoods expert). END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 Contracted under 607300.01.060 Monitoring and Evaluation Support Project DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. (THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK) ABSTRACT This is an end-of-program performance evaluation report for the Boma-Jonglei-Equatoria Landscape (BJEL) program covering the 2008-2017 whose purpose is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and impact of the BJEL program. The results of the evaluation will inform future programming of similar project activities by USAID/South Sudan, the implementing partner Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) entities and other donor organizations. The evaluation utilized a mixed-method approach, relying on quantitative and qualitative data from both primary and secondary sources, based on a set of indicators. The Evaluation interrogated information obtained and provided responses to the following five evaluation questions. a. How effective was the BJEL program in achieving project objectives? b. Did the project achieve the right focus and balance in terms of design, theory of change/development hypothesis, and strengthening strategies for sustainable safeguards of the wildlife population needs of South Sudan? c. -

Kordofan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Antiquorum), Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo

Quarterly conservation update – Kordofan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum), Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo October-December 2016 Mathias D’haen Czech University of Life Sciences (CULS), Kamýcká 961/129, 165 21 Prague 6-Suchdol, Czech Republic Introduction Garamba National Park (GNP) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was first established in 1938 by virtue of its uniqueness, one of the first Parks in Africa. Throughout its long history the Park was initially made famous with the world’s only elephant domestication program, coupled with its high numbers of elephant and buffalo, and home to the world’s last northern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) population. The Park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980 and on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 1996. Sadly, the Park’s infamy has increased through losing the last northern white rhino, and being plagued by numerous groups of rebels, in particular the Lord’s Resistance Army. In fact, the Park, being nestled in the far north-eastern corner of the country, is writing history every day again, not because of the countries’ own destabilised politics (the 2000km between the Park and the countries’ capital creates an efficient buffer), but because of its war against armed militia coming from within and neighbouring countries. GNP, and its adjacent Hunting Reserves, are also home to DRC’s only population of giraffe, historically named ‘Congo giraffe’ (Amube et al. 2009; De Merode et al. 2000; East 1999) but reclassified as they are genetically identical to other Kordofan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum) across Central Africa (Fennessy et al. -

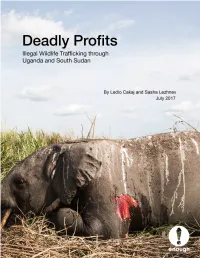

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant