A Strategy for Re-Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The LRA in Kafia Kingi

The LRA in Kafia Kingi The suspension of the Ugandan army operation in the Central African Republic (CAR) following the overthrow of the CAR regime in March 2013 may have given some respite to the LRA, which by the first quarter of 2013 appeared to be at its weakest in its long history. As of May 2013, there were some 500 LRA members in numerous small groups scattered in CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Sudan. Of these 500, about half were combatants, including up to 200 Ugandans and 50 low-ranking fighters abducted primarily from ethnic Zande com- munities in CAR, DRC, and South Sudan. At least one LRA group, including Kony, was reportedly based near the Dafak Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) garrison in the disputed area of Kafia Kingi for over a year, until February or early March 2013.1 Reports of LRA presence in Kafia Kingi have been made since early 2010. A recent publication contained a detailed account of the history of LRA groups in the area complete with satellite imagery showing the location of a possible LRA camp at close proximity to a SAF garrison.2 In April 2013, Col. al Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ada, the official SAF spokesperson, told the Sudanese official news agency SUNA, ‘ the report [showing an alleged LRA camp in Kafia Kingi] is baseless and rejected,’ adding, ‘SAF has no interest in adopting or sheltering rebels from other countries.’3 But interviews with former LRA members who recently defected confirm that a large LRA group of over 100 people, including LRA leader Joseph Kony, spent about a year in Kafia Kingi. -

'When Will This End and What Will It Take?'

‘When will this end and what will it take?’ People’s perspectives on addressing the Lord’s Resistance Army conflict Logo using multiply on layers November 2011 Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately ‘ With all the armies of the world here, why isn’t Kony dead yet and the conflict over? When will this end and what will it take?’ Civil society leader, Democratic Republic of Congo CHAD SUDAN Birao Southern Darfur Kafia Kingi Sam-Ouandja Western Wau Zemongo Game Bahr-El-Ghazal CENTRAL Reserve AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC Haut-Mbomou Djemah Bria Western Equatoria Bambouti Ezo Obo Nzara Juba Zemio Yambio Bambari Mbomou Mboki Maridi Rafai Central Magwi Bangassou Bangui Banda Equatoria Bas-Uélé GARAMBA Yei Nimule Ango PARK Lake Doruma Kitgum Turkana Niangara Dungu Duru Arua Faradje Haut Uélé Gulu Lira Bunia Soroti LakeLake AlbertAlbert DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO UGANDA Kampala LRA area of operation after Operation Lightning Thunder LakeLake VictoriaVictoria end of 2008–11 LRA area of operation during the Juba talks 2006–08 RWANDA LRA area of operation during Operation Iron Fist 2002–05 0 150 300km BURUNDI TANZANIA © Conciliation Resources. This map is intended for illustrative purposes only. Borders, names and other features are presented according to common practice in the region. Conciliation Resources take no position on whether this representation is legally or politically valid. Disclaimer Acknowledgements This document has been produced with the Conciliation Resources is grateful to Frank financial assistance of the European Union van Acker who conducted the research and and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Uganda. contributed to the analysis in this report. -

FROM the G7 to a D-10: Strengthening Democratic Cooperation for Today’S Challenges

FROM THE G7 TO THE D-10 : STRENGTHENING DEMOCRATIC COOPERATION FOR TODAY’S CHALLENGES FROM THE G7 TO A D-10: Strengthening Democratic Cooperation for Today’s Challenges Ash Jain and Matthew Kroenig (United States) With Tobias Bunde (Germany), Sophia Gaston (United Kingdom), and Yuichi Hosoya (Japan) ATLANTIC COUNCIL A Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. Democratic Order Initiative This report is a product of the Scowcroft Center’s Democratic Order Initiative, which is aimed at reenergizing American global leadership and strengthening cooperation among the world’s democracies in support of a rules-based democratic order. The authors would like to acknowledge Joel Kesselbrenner, Jeffrey Cimmino, Audrey Oien, and Paul Cormarie for their efforts and contributions to this report. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. © 2021 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

INTERNATIONAL GRID INTEGRATION: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia

Atlantic Council GLOBAL ENERGY CENTER INTERNATIONAL GRID INTEGRATION: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia PHILLIP CORNELL INTERNATIONAL GRID INTEGRATION: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia PHILLIP CORNELL ISBN: 978-1-61977-083-6 Cover Photo: Workers repair an electric grid in Hanoi, Vietnam, July 25, 2019. REUTERS/Kham This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not deter- mine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. January 2020 International Grid Integration: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia II ATLANTIC COUNCIL International Grid Integration: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia Contents Contents iii Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 1. Cross-Border Trade: A Boost for Economic Efficiency and Sustainability 5 2. Connecting in Asia 8 3. Technical and Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities 16 4. Strategic and Commercial Risks of GEI 17 5. US Grid Interconnection: Struggle to Connect and New Grid Technology Models 19 6. Conclusion: Political Values and Energy Infrastructure 24 About the Author 27 ATLANTIC COUNCIL III International Grid Integration: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia IV ATLANTIC COUNCIL International Grid Integration: Efficiencies, Vulnerabilities, and Strategic Implications in Asia Executive Summary he new decade is poised to be one of funda- with attractive financing and Chinese suppliers has raised mental change in the global electricity sector, concerns about debt traps and adequate standards, but with the widening cost advantages and spread transmission and smart grid technology can have addi- of renewable energy. -

The Atlantic Council and Bellingcat Are Guilty of War Propaganda. As

An essential dimension of humanitarian work is human rights investigations to identify violations and crimes. Human rights investigation organizations, in the digital age, are taking advantage of the growing prevalence of online citizen evidence and extractable data from what they often refer to as ‘open sources’ and social media TheThe AtlanticAtlantic CouncilCouncil andand BellingcatBellingcat areare guiltyguilty ofof warwar propaganda.propaganda. AsAs @ian56789@ian56789 wrotewrote toto mee in in a amessage: message: “The“The membersmembers ofof thethe AtlanticAtlantic CouncilCouncil andand DFRLabDFRLab shouldshould bebe indictedindicted asas accomplicesaccomplices toto WarWar Crimes,Crimes, forfor providingproviding actualactual materialmaterial supportsupport toto alal--QaedaQaeda terrorists,terrorists, andand forfor TreasonTreason (actively(actively supportingsupporting officialofficial enemiesenemies ofof thethe USUS && UK).UK). TheyThey shouldshould bebe spendingspending thethe restrest ofof theirtheir liveslives inin jailjail andand finedfined everyevery pennypenny they'vethey've got.”got.” AndAnd thosethose abusingabusing andand exploitingexploiting BanaBana alal--AbedAbed inin theirtheir ongoingongoing warwar propagandapropaganda shouldshould joinjoin themthem.. FromFrom https://www.rt.com/ophttps://www.rt.com/op--ed/431128ed/431128--banabana--alabedalabed--bellingcatbellingcat--atlanticatlantic--councilcouncil EvaEva Bartlett,Bartlett, JuneJune 29,29, 2018.2018. platforms. For the purpose of this discussion, we make use of the term ‘open source’ as it is specifically used by the organizations discussed here – we acknowledge that ‘open source’ as a term is often used in problematic ways in place of what is simply extractable, publicly available data – the term open source refers to accessible and editable software source code and in this paper’s context the term often misleadingly refers to datasets that have come at a high cost to the organization that procured them. -

The Gulf Rising: Defense Industrialization In

Atlantic Council BRENT SCOWCROFT CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL SECURITY THE GULF RISING Defense Industrialization in Saudi Arabia and the UAE Bilal Y. Saab THE GULF RISING Defense Industrialization in Saudi Arabia and the UAE Bilal Y. Saab Resident Senior Fellow for Middle East Security Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security at the Atlantic Council © May 2014 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1030 15th Street NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-055-3 Cover image: A visitor looks at a miniature model of a helicopter on display during the International Defense Exhibition and Conference (IDEX) at the Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre, February 18, 2013. Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary ..................................................................................... 2 The Author .............................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................. 7 Motivations ............................................................................................. 9 Pillars ..................................................................................................13 -

POLICY BRIEF--US Challenges and Choices in the Gulf: Energy Security

Policy Brief #3 The Atlantic Council of the United States, The Middle East Institute, The Middle East Policy Council, and The Stanley Foundation U.S. Challenges and Choices in the Gulf: Energy Security This policy brief is based on the discussion at the fifth in a jointly sponsored series of congressional staff briefings on “U.S. Challenges and Choices in the Gulf.” To receive information on future briefings, contact Jennifer Davies at [email protected]. With approximately 70 percent of the world’s known oil reserves, Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Iran and Iraq, are the world’s leading petroleum exporters. Gulf oil exports (and, therefore, world oil prices) are largely governed by the political and economic dynamics of the Gulf region – suggesting that U.S. leaders have a substantial stake in understanding these dynamics generally and, specifically, how they impact U.S. energy security concerns. Oil plays a key role in U.S. energy security, providing approximately 40 percent of the total annual energy use of the United States (measured in trillion Btu). Indeed, the United States is the world’s number one consumer of oil, using 20 million barrels of oil per day, or one-fifth of the world total. Of these 20 million barrels, the United States imports 9 million, as its domestic production is insufficient to satisfy the country’s needs. This brief addresses four fundamental questions regarding the current and likely future energy needs of the United States. 1. Is the United States “dependent” on Arab/Gulf oil? This often-asked, but misleading question begs several responses. -

Dominic Ongwen's Domino Effect

DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT HOW THE FALLOUT FROM A FORMER CHILD SOLDIER’S DEFECTION IS UNDERMINING JOSEPH KONY’S CONTROL OVER THE LRA JANUARY 2017 DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Map: Dominic Ongwen’s domino effect on the LRA I. Kony’s grip begins to loosen 4 Map: LRA combatants killed, 2012–2016 II. The fallout from the Ongwen saga 7 Photo: Achaye Doctor and Kidega Alala III. Achaye’s splinter group regroups and recruits in DRC 9 Photo: Children abducted by Achaye’s splinter group IV. A fractured LRA targets eastern CAR 11 Graph: Abductions by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 Map: Attacks by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 V. Encouraging defections from a fractured LRA 15 Graph: The decline of the LRA’s combatant force, 1999–2016 Conclusion 19 About The LRA Crisis Tracker & Contributors 20 LRA CRISIS TRACKER LRA CRISIS TRACKER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since founding the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda in the late 1980s, Joseph Kony’s control over the group’s command structure has been remarkably durable. Despite having no formal military training, he has motivated and ruled LRA members with a mixture of harsh discipline, incentives, and clever manipulation. When necessary, he has demoted or executed dozens of commanders that he perceived as threats to his power. Though Kony still commands the LRA, the weakening of his grip over the group’s command structure has been exposed by a dramatic series of events involving former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen. In late 2014, a group of Ugandan LRA officers, including Ongwen, began plotting to defect from the LRA. -

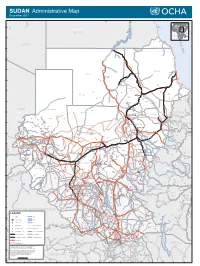

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

The Egyptian Fortress on Uronarti in the Late Middle Kingdom

and omitting any later additions. As such, it would be fair to Evolving Communities: The argue that our notion of the spatial organization of these sites and the lived environment is more or less petrified at Egyptian fortress on Uronarti their moment of foundation. in the Late Middle Kingdom To start to rectify these shortcomings, we have begun a series of small, targeted excavations within the fortress; we Christian Knoblauch and Laurel Bestock are combining this new data with a reanalysis of unpub- lished field notes from the Harvard/BMFA excavations as Uronarti is an island in the Batn el-Hagar approximately 5km well as incorporating important new studies on the finds from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom border with Kush at the from that excavation, for example that on the sealings by Semna Gorge. The main cultural significance of the island Penacho (2015). The current paper demonstrates how this stems from the decision to erect a large trapezoidal mnnw modest approach can yield valuable results and contribute fortress on the highest hill of the island during the reign of to a model for the development of Uronarti and the Semna Senwosret III. Together with the contemporary fortresses at Region during the Late Middle Kingdom and early Second Semna West, Kumma, Semna South and Shalfak, Uronarti Intermediate Period. constituted just one component of an extensive fortified zone at the southern-most point of direct Egyptian control. Block III Like most of these sites (excepting Semna South), Uronarti The area selected for reinvestigation in 2015-2016 was a was excavated early in the history of Sudanese archaeology small 150m2 part of Block III (Figure 1, Plate 1) directly by the Harvard/Boston Museum of Fine Arts mission in the to the local south of the treasury/granary complex (Blocks late 1920’s (Dunham 1967; Reisner 1929; 1955; 1960; Wheeler IV-VI) (Dunham 1967, 7-8; Kemp 1986) and to the north 1931), and was long believed to have been submerged by of the building probably to be identified as the residence of Lake Nubia (Welsby 2004). -

Jean-Nicolas Bach and Clément Deshayes Sudanese Internal

Sudan Jean-Nicolas Bach and Clément Deshayes Sudanese internal politics remained tense, both within the regime and in its rela- tions with many sectors of society. Within the regime, President Omar al-Bashir announced the formation of a new government emerging from the ‘National Dia- logue’. But the composition of and participants in this Government of National Accord (or Consensus) were far from representing a solid basis for peaceful political competition. Tensions also remained very high within many segments of society, particularly student movements and (armed) groups in peripheral regions. Hun- dreds of political prisoners remained in jail. Tensions reached their peak in Darfur in May, when a joint attack was launched by rebel groups based in Libya (SLA/Minni Minawi) and South Sudan (SLA/Transi- tion Council). They were repelled but the attack sent a message to the international community that the Darfur war was not over. An end to the war was one of the preconditions raised by the US in 2016–17 for lifting its sanctions on Sudan, imposed back in 1997. The negotiations during the year and the eventual lifting of the sanc- tions in October made 2017 a very important year. Sudan had a broader policy aimed at normalising Khartoum’s foreign relations. Thus, al-Bashir’s regime remained an important partner with the EU regarding migration policies (it hosted a thematic © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���8 | doi:��.��63/9789004367630_04� 378 Bach and deshayes meeting of the Khartoum Process) and skilfully managed to remain neutral towards the Gulf crisis, in which Saudi Arabia and the UAE opposed Qatar.