Jolanta Tubielewicz Superstitions, Magic and Mantic Practices in the Heian Period - Part Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Die Riten Des Yoshida Shinto

KAPITEL 5 Die Riten des Yoshida Shinto Das Ritualwesen war das am eifersüchtigsten gehütete Geheimnis des Yoshida Shinto, sein wichtigstes Kapital. Nur Auserwählte durften an Yoshida Riten teilhaben oder gar so weit eingeweiht werden, daß sie selbst in der Lage waren, einen Ritus abzuhalten. Diese zentrale Be- deutung hatten die Riten sicher auch schon für Kanetomos Vorfah- ren. Es ist anzunehmen, daß die Urabe, abgesehen von ihren offizi- ellen priesterlichen Aufgaben, wie sie z.B. in den Engi-shiki festgelegt sind, bereits als ietsukasa bei diversen adeligen Familien private Riten vollzogen, die sie natürlich so weit als möglich geheim halten muß- ten, um ihre priesterliche Monopolstellung halten und erblich weiter- geben zu können. Ein Austausch von geheimen, Glück, Wohlstand oder Schutz vor Krankheiten versprechenden Zeremonien gegen ge- sellschaftliche Anerkennung und materielle Privilegien zwischen den Urabe und der höheren Hofaristokratie fand sicher schon in der späten Heian-Zeit statt, wurde allerdings in der Kamakura Zeit, als das offizielle Hofzeremoniell immer stärker reduziert wurde, für den Bestand der Familie umso notwendiger. Dieser Austausch verlief offenbar über lange Zeit in sehr genau festgelegten Bahnen: Eine Handvoll mächtiger Familien, alle aus dem Stammhaus Fujiwara, dürften die einzigen gewesen sein, die in den Genuß von privaten Urabe-Riten gelangen konnten. Bis weit in die Muromachi-Zeit hin- ein existierte die Spitze der Hofgesellschaft als einziger Orientie- rungspunkt der Priesterfamilie. Mit dem Ōnin-Krieg wurde aber auch diese Grundlage in Frage gestellt, da die Mentoren der Familie selbst zu Bedürftigen wurden. Selbst der große Ichijō Kaneyoshi mußte in dieser Zeit sein Über- leben durch Anbieten seines Wissens und seiner Schriften an mächti- ge Kriegsherren wie z.B. -

Contemporary Popular Beliefs in Japan

Hugvísindasvið Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir September 2010 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindadeild Japanskt mál og menning Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir Kt.: 130784-3219 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2010 Abstract This thesis discusses contemporary popular beliefs in Japan. It asks the questions what superstitions are generally known to Japanese people and if they have any affects on their behavior and daily lives. The thesis is divided into four main chapters. The introduction examines what is normally considered to be superstitious beliefs as well as Japanese superstition in general. The second chapter handles the methodology of the survey written and distributed by the author. Third chapter is on the background research and analysis which is divided into smaller chapters each covering different categories of superstitions that can be found in Japan. Superstitions related to childhood, death and funerals, lucky charms like omamori and maneki neko and various lucky days and years especially yakudoshi and hinoeuma are closely examined. The fourth and last chapter contains the conclusion and discussion which covers briefly the results of the survey and what other things might be of interest to investigate further. Table of contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 What is superstition? ............................................................................................... -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Walking Japan

Walking Japan 11 Days Walking Japan This enchanting journey through Japan combines stunning hiking with timeless tradition. Beginning in the old imperial city of Kyoto and ending in modern Tokyo, our itinerary follows the Nakasendo, a network of ancient trade routes once used to travel from Kyoto to the provincial towns of the Kiso Valley. By way of temples, shrines, and hamlets, you'll take in ethereal landscapes of lush gardens, misty forests and possibly the bloom of cherry blossoms. Along the way, enjoy generous Japanese hospitality in a shukubo (temple lodging) and family-run inns, and the contrasts between old and new in this magical land. Details Testimonials Arrive: Kyoto, Japan "A finely tuned and brilliantly led trip that gives the traveler a great take on Depart: Tokyo, Japan Japanese culture." John W. Duration: 11 Days Group Size: 5-12 Guests "Our three-generation family had a wonderful experience hiking village to Minimum Age: 12 Years Old village on the Nakasendo Trail with MT Sobek." Activity Level: Level 3 Mary and David O. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek's immersive Walking Our itinerary has been crafted Walking Japan is an MT Sobek Japan itinerary offers you the for personal achievement, classic that we've run for over chance to explore idyllic landscapes allowing you to carry nothing 10 years. It is the perfect way on foot with expert local guides. but a daypack as we transport to get to the heart of Japan. your belongings to each inn. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Moderately paced hikes up Enjoy stays in traditional ryokans Spring and fall temperatures to 4-9 miles a day on paved (inns) — many with onsen (hot range from 50°F to the and dirt trails, plus cultural springs) — and comfortable high 70°'s F. -

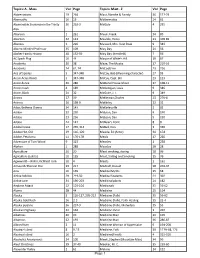

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Shintō and Buddhism: the Japanese Homogeneous Blend

SHINTŌ AND BUDDHISM: THE JAPANESE HOMOGENEOUS BLEND BIB 590 Guided Research Project Stephen Oliver Canter Dr. Clayton Lindstam Adam Christmas Course Instructors A course paper presented to the Master of Ministry Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Ministry Trinity Baptist College February 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Stephen O. Canter All rights reserved Now therefore fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which your fathers served −Joshua TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vii Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: The History of Japanese Religion..................................................................3 The History of Shintō...............................................................................................5 The Mythical Background of Shintō The Early History of Shintō The History of Buddhism.......................................................................................21 The Founder −− Siddhartha Gautama Buddhism in China Buddhism in Korea and Japan The History of the Blending ..................................................................................32 The Sects That Were Founded after the Blend ......................................................36 Pre-War History (WWII) .......................................................................................39 -

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

Appendix B: Transcript Bravely Default

Appendix B: Transcript Bravely Default Applied JGRL usage tagging styles: Gender-conforming Gender-contradicting Gender-neutral (used to tag text which is easily confusable as JGRL) Gender-ambiguous Notes regarding preceding text line Finally, instances of above tagging styles applied to TT indicate points of interest concerning translation. One additional tagging style is specifically used for TT tagging: Alternate translations of ‘you’ 『ブレイブリーデフォルトフォーザ・シークウェル』 [BUREIBURII DEFORUTO FOOZA・ SHIIKUWERU]— —“BRAVELY DEFAULT” 1. 『オープニングムービー』 [Oopuningu Muubii] OPENING CINEMATICS AIRY anata, ii me wo shiteru wa ne! nan tte iu ka. sekininkan ga tsuyo-sou de, ichi-do kimeta koto wa kanarazu yaritoosu! tte kanji da wa. sonna anata ni zehi mite-moraitai mono ga aru no yo. ii? zettai ni me wo sorashicha DAME yo. saigo made yaritokete ne. sore ja, saki ni itteru wa. Oh, hello. I see fire in those eyes! How do I put it? They’ve a strong sense of duty. Like whatever you start, you’ll always see through, no matter what! If you’ll permit me, there’s something I’d very much like to show you. But… First, I just need to hear it from you. Say that you’ll stay. Till the very end. With that done. Let’s get you on your way! ACOLYTES KURISUTARU no kagayaki ga masumasu yowatte-orimasu. nanika no yochou de wa nai deshou ka. hayaku dou ni ka shimasen to. The crystal’s glow wanes by the hour. It’s fading light augurs a greater darkness. Something must be done! AGNÈS wakatteimasu. Leave all to me. AGNÈS~TO PLAYER watashi no namae wa, ANIESU OBURIIJU. -

Tobacco Accessories

Tobacco Accessories Japanese men in the Edo period (1615–1868) wore various accessories suspended from their kimono waist sashes, including tobacco implements. Tobacco was smoked with long pipes (kiseru), which were stored in pipe cases of various designs. The objects shown here include a tobacco pouch and pipe case set as well as individual pipe cases and lacquered tobacco containers (inro). A Japanese woodblock print depicting tobacco 長谷川一虎作 邯鄲夢に牡丹唐草文革 煙管 銘「千賀政光」 籐製網代編無双筒 昭玉作 猩々網代編籐地象牙珊瑚無双筒 accessories can be seen on the 提げ煙草入れ Pipe (kiseru) Pipe case (musozutsu type) Pipe case (musozutsu type) with the Matched tobacco set with the Approx. 1850–1900 Approx. 1800–1900 drunken sea sprite Shojo dancing other side of this placard. design of Lu Sheng’s dream and Signed Chiga Masamitsu Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period with sake cup peony scrolls Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period (1868–1912) Approx. 1800–1900 All objects were made in Approx. 1850–1900 (1868–1912) Rattan and copper alloy By Shogyoku (Japanese, active 19th Japan and are from The Avery By Hasegawa Ikko (Japanese, active Copper alloy with gold and silver B70M25 century) Brundage Collection. 19th century) B70M18 A musozutsu is a type of pipe case with Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period Leather with lacquer, ivory, and bronze This lavish tobacco set comprises two cylindrical parts, one of which fits (1868–1912) with gilding a tobacco pouch, pipe case, pipe, perfectly into the other. While such cases Rattan with coral, ivory, and lacquer B70M18 netsuke toggle, and a connecting were made from a variety of materials, B70M23 chain made from segments of carved this case was fashioned from finely ivory openwork.