Significance of Touch and Eye Contact in the Polish Deaf Community During Conversations in Polish Sign Language: Ethnographic Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn to Use Signpuddle 1.0 on The

Some Dictionaries: ™ SignPuddle Online American Sign Language www.SignBank.org/signpuddle Arabic Sign Languages Brazilian Sign Language British Sign Language Colombian Sign Language Czech Sign Language Danish Sign Language Finnish Sign Language Flemish Sign Language French Sign Language German Sign Language Greek Sign Language International Sign Languages Irish Sign Language Italian Sign Language Japanese Sign Language Maltese Sign Language Come Splash in a Sign Puddle! Netherlands Sign Language 1. FREE on the web! Nicaraguan Sign Language Northern Ireland Sign Language 2. Search Sign Language Dictionaries. Norwegian Sign Language 3. Create your own signs and add them. Polish Sign Language 4. Send email in SignWriting®. Quebec Sign Language 5. Translate words to SignWriting. Spanish Sign Language 6. Create documents with SignWriting. Swiss Sign Languages 7. Have fun sharing signs on the internet! Taiwan Sign Language ...and others... http://www.SignBank.org/signpuddle Search by Words 1. Click on the icon: Search by Words 2. In the Search field: Type a word or a letter. 3. Press the Search button. 4. All the signs that use that word will list for you in SignWriting. 5. You can then copy the sign, or drag and drop it, into other documents. http://www.SignBank.org/signpuddle Search by Signs 1. Click on the icon: Search by Signs 2. In the Search field: Type a word or a letter. 3. Press the Search button. 4. The signs will list in small size. 5. Click on the small sign you want, and a larger version will appear... http://www.SignBank.org/signpuddle Search by Symbols 1. -

What Corpus-Based Research on Negation in Auslan and PJM Tells Us About Building and Using Sign Language Corpora

What Corpus-Based Research on Negation in Auslan and PJM Tells Us About Building and Using Sign Language Corpora Anna Kuder1, Joanna Filipczak1, Piotr Mostowski1, Paweł Rutkowski1, Trevor Johnston2 1Section for Sign Linguistics, Faculty of the Polish Studies, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00-927 Warsaw, Poland 2Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Human Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2109 {anna.kuder, j.filipczak, piotr.mostowski, p.rutkowski}@uw.edu.pl, [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we would like to discuss our current work on negation in Auslan (Australian Sign Language) and PJM (Polish Sign Language, polski język migowy) as an example of experience in using sign language corpus data for research purposes. We describe how we prepared the data for two detailed empirical studies, given similarities and differences between the Australian and Polish corpus projects. We present our findings on negation in both languages, which turn out to be surprisingly similar. At the same time, what the two corpus studies show seems to be quite different from many previous descriptions of sign language negation found in the literature. Some remarks on how to effectively plan and carry out the annotation process of sign language texts are outlined at the end of the present paper, as they might be helpful to other researchers working on designing a corpus. Our work leads to two main conclusions: (1) in many cases, usage data may not be easily reconciled with intuitions and assumptions about how sign languages function and what their grammatical characteristics are like, (2) in order to obtain representative and reliable data from large-scale corpora one needs to plan and carry out the annotation process very thoroughly. -

IFHOHYP Newsletter 1/2007

IFHOHYP NEWS Summer 2007 The International Federation of Hard of Hearing Young People Magazine New Trends in Educating Hearing Impaired People by Svetoslava Saeva (Bulgaria) In the period 21-25 March 2007 an International Contact Seminar New Trends in Educating Hearing Impaired People was held for the first time in Bratislava, Slovakia (http://akademia.exs.sk). The seminar is realized as a main activity of a project of the European Culture Society, Bratislava and is financially supported by: Youth Programme – Action 5, Open Society Fund and Austrian Culture Forum. All activities were interpreted into English, Slovak, Slovak Sign language and International Sign. The seminar was under the auspices of Mr. Dušan Čaplovič – Deputy Prime Minister of the Government of Slovakia for Knowledge-Based Society, European Affairs, Human Rights and Minorities and Mrs. Viera Tomanová – Minister of Labour, Social Affairs and Family in Slovakia. The seminar was divided into two main parts concerning activities in the whole period. Svetoslava (in the right) The first part was on 22 March when Open Public Seminar was realized in the capital of Slovakia – Bratislava. There were more than 110 people from different countries that took part in the seminar. Many of the participants were hearing impaired. There were many interesting presentations about technologies and innovations in education and preparation for universities as well as for the labour market of hearing impaired and deaf people. Mr. Andrej Buday – a Slovak project manager and president of the Association of Driving Schools in Slovak Republic shared very valuable experience about teaching deaf and hearing impaired people how to drive correctly and safely. -

Stakeholders' Views on Use of Sign Language Alone As a Medium Of

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SPECIAL EDUCATION Vol.33, No.1, 2018 Stakeholders’ Views on Use of Sign Language Alone as a Medium of Instruction for the Hearing Impaired in Zambian Primary Schools Mandyata Joseph, Kamukwamba Kapansa Lizzie, School of Education, University of Zambia ([email protected]) Abstract The study examined views of stakeholders on the use of Sign Language as a medium of instruction in the learning of hearing impaired in primary schools of Lusaka, Zambia. A case study design supported by qualitative methods was used. The sample size was 57, consisting of teachers, pupils, curriculum specialist, education standards officers, lecturers and advocators on the rights of persons with disabilities. Purposive sampling techniques to selected the sample, interview and focused group discussion guides were tools for data collection. The study revealed significant differences in views of stakeholders on use of Sign Language alone as medium of instruction. While most participants felt sign language alone was ideal for learning, others believed learners needed exposure to total communication (combination of oral and sign language) to learn better. Those who felt using sign language alone was better, believed the practice had more positive effects on learning and that use of oral language, total communication often led to confusion in classroom communication among learners with hearing impairments. Participants who opposed use of sign language alone were of the view teachers: were ill-prepared; signs were limited in scope; education system lacked instructional language policy and learning environment were inappropriate to support use of sign language alone in the learning process. The study recommended strengthening of training of sign language teachers and introduction of sign language as an academic subject before it can be used as the sole medium of classroom instruction in the Zambian primary schools. -

Sign Language Legislation in the European Union 4

Sign Language Legislation in the European Union Mark Wheatley & Annika Pabsch European Union of the Deaf Brussels, Belgium 3 Sign Language Legislation in the European Union All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the authors. ISBN 978-90-816-3390-1 © European Union of the Deaf, September 2012. Printed at Brussels, Belgium. Design: Churchill’s I/S- www.churchills.dk This publication was sponsored by Significan’t Significan’t is a (Deaf and Sign Language led ) social business that was established in 2003 and its Managing Director, Jeff McWhinney, was the CEO of the British Deaf Association when it secured a verbal recognition of BSL as one of UK official languages by a Minister of the UK Government. SignVideo is committed to delivering the best service and support to its customers. Today SignVideo provides immediate access to high quality video relay service and video interpreters for health, public and voluntary services, transforming access and career prospects for Deaf people in employment and empowering Deaf entrepreneurs in their own businesses. www.signvideo.co.uk 4 Contents Welcome message by EUD President Berglind Stefánsdóttir ..................... 6 Foreword by Dr Ádám Kósa, MEP ................................................................ -

Marcin Mizak Sign Language – a Real and Natural Language

LUBELSKIE MATERIAŁY NEOFILOLOGICZNE NR 35, 2011 Marcin Mizak Sign Language – A Real and Natural Language 1. Introduction It seems reasonable to begin a discussion on the “realness” and “naturalness” of sign language by comparing it to other human languages of whose “real” and “natural” status there can be no doubt whatsoever. They will be our reference point in the process of establishing the status of sign language. The assumption being made in this paper is that all real and natural languages share certain characteristics with one another, that they all behave in a certain way and that certain things happen to all of them. If it transpires that the same characteristics and behaviours are also shared by sign language and that whatever happens to real and natural languages also happens to sign language then the inevitable conclusion follows: sign language is indeed a real and natural language 1. 2. The number of languages in the world One of the first things to be noticed about real and natural languages is their great number. Ethnologue: Languages of the World , one of the most reliable and comprehensive encyclopedic reference publications, catalogues in its 16 th edition of 2009 6,909 known living languages in 1 The designation “sign language,” as used in this article, refers to the languages used within communities of the deaf. American Sign Language, for example, is a sign language in this sense. Artificially devised systems, such as Signed English, or Manual English, are not sign languages in this sense. Sign Language – A Real and Natural Language 51 the world today 2. -

Capturing the Language of the Deaf

Linguistics Capturing the Language of the Deaf Dr. Paweł Rutkowski insight University of Warsaw magine we were born in a society in which every- one around us communicates in a language we Idon’t understand. What’s more, it’s a language we are not even able to experience with our senses. Now imagine that in spite of this, everyone expects us to master that language in order to help us live “easier,” so that we can function “normally” in society. So that we do not have to be different. This is how, in very simple terms, we can describe the situation faced by Paweł Rutkowski, the Deaf in various countries, including in Poland. Note the preference for the term Deaf (or Pol- PhD is the creator of the ish: Głusi), rather than hearing-impaired (Polish: Section for Sign niesłyszący). While the hearing community may see Linguistics at the the term hearing-impaired (or niesłyszący) as neutral, University of Warsaw. He the Deaf want to be seen through the prism of what specializes in the syntax they are, rather than what they are NOT or in terms of natural languages, of how they are perceived to be defective. Writing the with particular emphasis word Deaf (or Głusi) with a capital letter is intended to on Polish Sign Language define deafness as a major indicator of a certain cul- (PLM). He has authored tural and linguistic identity (similar to other minority or co-authored more groups in Poland, such as Silesians or Kashubians), than a hundred research publications and not to stigmatize their disabilities. -

Sign Languages

200-210 Sign languages 200 Arık, Engin: Describing motion events in sign languages. – PSiCL 46/4, 2010, 367-390. 201 Buceva, Pavlina; Čakărova, Krasimira: Za njakoi specifiki na žestomimičnija ezik, izpolzvan ot sluchouvredeni lica. – ESOL 7/1, 2009, 73-79 | On some specific features of the sign language used by children with hearing disorders. 202 Dammeyer, Jesper: Tegnsprogsforskning : om tegnsprogets bidrag til viden om sprog. – SSS 3/2, 2012, 31-46 | Sign language research : on the contribution of sign language to the knowledge of languages | E. ab | Electronic publ. 203 Deaf around the world : the impact of language / Ed. by Gaurav Mathur and Donna Jo Napoli. – Oxford : Oxford UP, 2011. – xviii, 398 p. 204 Fischer, Susan D.: Sign languages East and West. – (34), 3-15. 205 Formational units in sign languages / Ed. by Rachel Channon ; Harry van der Hulst. – Berlin : De Gruyter Mouton ; Nijmegen : Ishara Press, 2011. – vi, 346 p. – (Sign language typology ; 3) | Not analyzed. 206 Franklin, Amy; Giannakidou, Anastasia; Goldin-Meadow, Susan: Negation, questions, and structure building in a homesign system. – Cognition 118/3, 2011, 398-416. 207 Gebarentaalwetenschap : een inleiding / Onder red. van Anne E. Baker ; Beppie van den Bogaerde ; Roland Pfau ; Trude Schermer. – Deventer : Van Tricht, 2008. – 328 p. 208 Kendon, Adam: A history of the study of Australian Aboriginal sign languages. – (50), 383-402. 209 Kendon, Adam: Sign languages of Aboriginal Australia : cultural, semi- otic and communicative perspectives. – Cambridge : Cambridge UP, 2013. – 562 p. | First publ. 1988; cf. 629. 210 Kudła, Marcin: How to sign the other : on attributive ethnonyms in sign languages. – PFFJ 2014, 81-92 | Pol. -

Prepub Uncorrected Version

“LeeSchoenfeld-book” — 2021/1/11 — 15:30 — page 198 — #206 CHAPTER 8 Clause-Initial Vs in Sign Languages: Scene-Setters DONNA JO NAPOLI AND RACHEL SUTTON–SPENCE 8.1 INTRODUCTION Linguists often talk about the skeletal organization of a clause as involving three major elements: S, V, and sometimes O, where often that organization is taken as a major typological classifier (Greenberg 1963, and many since). With that terminology, this chapter concerns the semantics of clauses that have V as their first articulated major element in the sign languages of Brazil (Libras), Australia (Auslan), Britain (BSL), the Netherlands (Nederlandse Gebarentaal or NGT), and Sweden (Svenskt teckenspråk or STS). We will show that clauses in which the predicate and all its arguments are separately and manually expressed begin with the V only under well- circumscribed semantic conditions. We argue that the findings here are due to the iconic nature of sign languages and, thus, should hold of sign languages in general. 8.2 GENERAL CAVEATS Talking about clauses in sign languages is problematic because sign linguists have not settled on consistent syntactic criteria for determining what counts as a clause or a complete sentence (Crasborn 2007; Jartunen 2008). Com- plications arise especially when there is repetition of elements, particularly repetition of predicates (Fischer and Janis 1990; Kegl 1990; Matsuoka 1997, 1999; Bø 2010). We do, however, use the term clause in this chapter, where we rely on two factors in the analysis of our data. First, we rely on the semantic Parameters of Predicate Fronting. Vera Lee-Schoenfeld, Oxford University Press (2021). -

Quantitative Survey of the State of the Art in Sign Language Recognition

QUANTITATIVE SURVEY OF THE STATE OF THE ART IN SIGN LANGUAGE RECOGNITION Oscar Koller∗ Speech and Language Microsoft Munich, Germany [email protected] September 1, 2020 ABSTRACT This work presents a meta study covering around 300 published sign language recognition papers with over 400 experimental results. It includes most papers between the start of the field in 1983 and 2020. Additionally, it covers a fine-grained analysis on over 25 studies that have compared their recognition approaches on RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014, the standard benchmark task of the field. Research in the domain of sign language recognition has progressed significantly in the last decade, reaching a point where the task attracts much more attention than ever before. This study compiles the state of the art in a concise way to help advance the field and reveal open questions. Moreover, all of this meta study’s source data is made public, easing future work with it and further expansion. The analyzed papers have been manually labeled with a set of categories. The data reveals many insights, such as, among others, shifts in the field from intrusive to non-intrusive capturing, from local to global features and the lack of non-manual parameters included in medium and larger vocabulary recognition systems. Surprisingly, RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather with a vocabulary of 1080 signs represents the only resource for large vocabulary continuous sign language recognition benchmarking world wide. Keywords Sign Language Recognition · Survey · Meta Study · State of the Art Analysis 1 Introduction Since recently, automatic sign language recognition experiences significantly more attention by the community. -

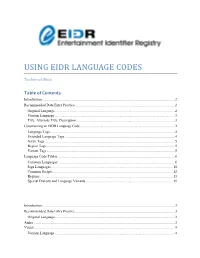

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags ............................................................................................................................................. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Status of Sign Languages in Europe

Report A comparative analysis of the status of sign languages in Europe ©Nina Timmermans, consultant Strasbourg, France December 2003 Table of contents Executive summary ………………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter 1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 4 Chapter 2 European Union ……………………………………………………………. 5 2.1 European Parliament Resolution on Sign Languages for Deaf People (1988). 5 2.2 European Parliament Resolution on Sign Languages (1998) ……………….. 6 2.3 European Commission Action Plan promoting language learning and linguistic diversity (2003) …………………………………………………… 6 2.4 European Parliament Report on the position of regional and minority languages in the European Union (2003) ……………………………………. 7 2.5 Council and representatives of the governments of the member states Resolution on equality of opportunity for people with disabilities (1996) ….. 8 2.6 Council Resolution on equal opportunities for pupils and students with disabilities in education and training (2003) ………………………………… 9 2.7 EU funded project in Finland: virtual study and career counselling centre in sign language .……………………………………………………………… 10 Chapter 3 Council of Europe ………………………………………………………… 11 3.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 11 3.2 The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (1992) ………. 12 3.3 Flensburg Recommendations on the Implementation of Policy Measures for Regional or Minority Languages (2000) …………………………………… 13 3.4 Parliamentary Assembly Recommendation 1492 (2001) on the rights of national minorities …………………………………………………………. 13 3.5 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights report on protection of sign languages in the member states of the Council of Europe (2003) ……….… 15 3.6 Parliamentary Assembly Recommendation 1598 (2003) on the protection of sign languages in the member states of the Council of Europe ………….… 15 Chapter 4 Constitution and legislation ………………………………..…………….. 17 4.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………..….….… 17 4.2 Constitutional recognition of sign language ……………………...……..….