Netherhouse Farm, Sewardstone, Epping Forest, Essex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abridge Buckhurst Hill Chigwell Coopersale Epping Fyfield

Abridge Shell Garage, London Road Buckhurst Hill Buckhurst Hill Library, 165 Queen’s Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Buckhurst Hill Convenience Store, 167 Queen’s Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Premier & Post Office, 38 Station Way (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Queen’s Food & Wine, 8 Lower Queen’s Road Valley Mini Market, 158 Loughton Way Valley News, 50 Station Way Waitrose, Queens Road Chigwell Lambourne News, Chigwell Row Limes Centre, The Cobdens (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Chigwell Parish Council, Hainault Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) L. G. Mead & Son, 19 Brook Parade (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Budgens Supermarket, Limes Avenue Coopersale Hambrook, 29 Parklands Handy Stores, 30 Parklands Epping Allnut Stores, 33a Allnuts Road Epping Newsagent, 83 High Street (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Epping Forest District Council Civic Offices, 323 High Street (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) Epping Library, St. Johns Road (Coronaviris pandemic – this outlet is temporarily closed) House 2 Home, 295 High Street M&S Simply Food, 237-243 High Street Tesco, 77-79 High Street Fyfield Fyfield Post Office, Ongar Road High Ongar Village Store, The Street Loughton Aldi, Epping Forest Shopping Park Baylis News, 159 High Road Epping Forest District Council Loughton Office, 63 The Broadway -

BTR Works, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex

BTR Works, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex An Archaeological Evaluation for Tesco Stores Ltd by Sarah Coles Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code WABT03 June 2003 Summary Site name: BTR Works Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex Grid reference: TL 3860 0035 Site activity: Evaluation Date and duration of project: 22nd–28th May Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Sarah Coles Site code: WABT03 Area of site: 3.2 ha Summary of results: No archaeological deposits or artefacts were observed on site. It would appear the entire site was truncated of topsoil prior to the construction of the BTR works. Several areas disturbance were noted. A photographic record was made of the buildings prior to demolition. Monuments identified: None Location and reference of archive: The site archive is currently held by Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47-49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading, Berkshire RG1 5NR and will be deposited with Waltham Abbey Museum in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford9 20.06.03 Steve Preston9 20.06.03 i BTR Works, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex An Archaeological Evaluation by Sarah Coles Report 01/69b Introduction This report documents the results of an archaeological field evaluation carried out at the former BTR Works, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex (TL 3860 0035) (Fig. 1). The work was commissioned by Mr Mike Ward of Tesco Stores Ltd, PO Box 400, Cirrus Building, Shire Park, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, AL7 1AB. -

Highway Verge Management

HIGHWAY VERGE MANAGEMEN T Planning and Development Note Date 23rd January 2019 Version Number 2 Highway Verge Management Review Date 30th March 2024 Author Geoff Sinclair/Richard Edmonds Highway Verge Management PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT NOTE INTRODUCTION Planning and Development Notes (PDN) aim to review and collate the City Corporation’s (CoL) property management issues for key activities, alongside other management considerations, to give an overview of current practice and outline longer term plans. The information gathered in each report will be used by the CoL to prioritise work and spending, in order to ensure firstly that the COL’s legal obligations are met, and secondly that resources are used in an efficient manner. The PDNs have been developed based on the current resource allocation to each activity. An important part of each PDN is the identification of any potential enhancement projects that require additional support. The information gathered in each report will be used by CoL to prioritise spending as part of the development of the 2019-29 Management Strategy and 2019-2022 Business Plan for Epping Forest. Each PDN will aim to follow the same structure, outlined below though sometimes not all sections will be relevant: Background – a brief description of the activity being covered; Existing Management Program – A summary of the nature and scale of the activity covered; Property Management Issues – a list of identified operational and health and safety risk management issues for the activity; Management Considerations -

An Assessment of the Feasibility of Annual Monitoring of Winter Gull Roosts in the UK and Possible Outputs from Such a Scheme

BTO Research Report No. 483 An assessment of the feasibility of annual monitoring of winter gull roosts in the UK and possible outputs from such a scheme Authors N.H.K. Burton, I.M.D. Maclean & G.E. Austin Report of work carried out by The British Trust for Ornithology under contract to Natural England November 2007 British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures .........................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................7 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................9 2. METHODS............................................................................................................................11 2.1 Identification of Sites Where Gull Numbers Surpass 1% Thresholds or Exceed 20,000 Birds ...........................................................................................................................11 2.2 Comparison of Species’ Indices Produced Using Wings and Webs Core Counts and Their Representativeness..............................................................................................12 -

Media Pack WATP

Waltham Abbey Press and media information Produced by Waltham Abbey Town Partnership (WATP) www.watp.org.uk 1 Table of Contents Why be based at Waltham Abbey, the tranquil Market Town set in the Lea Valley?----------------------------------------4 What's so special about Waltham Abbey?-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Waltham Abbey Gateway to England--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 Local people to interview-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Experience Waltham Abbey----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Waltham Abbey History through the ages---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7 Indoor locations for filming and interviewing----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------12 Indoor locations for filming and interviewing----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 Outdoor locations for filming and -

Gypsies and Travellers Development Plan Consultation on Options

Gypsies and Travellers Development Plan Consultation on Options 14.20 Potential New Sites - around There is a planning brief for the site, now some- Waltham Abbey, Roydon, Nazeing and what out of date and no longer in conformity Sewardstone with national policy. The future of this site/ 14.21 There are a number of potential sites to area will be considered further as part of the the north and south of Waltham Abbey. Core Strategy. Any development, if the location were found acceptable, would have to improve 14.22 The sites to the north lie along Crooked open vistas from Crooked Mile, and if necessary Mile, one at or in a yard area to the rear of would have to enact traffic safety measures the derelict Lea Valley Nursery It could take on Crooked Mile. Views from Paternoster Hill around 10 pitches, either as a standalone site would be an issue. As with all green belt sites to the rear or as part of a wider development, the dereliction by itself is not a material plan- if such a development were to be found ac- ning consideration, and neither are considera- ceptable. This has been removed from the area tions over whether the existing owner should permitted for glasshouse extensions in the Lo- be rewarded or punished. cal Plan Alterations. It should be noted that this policy (E13) is a permissive one, and does not 14.24 Slightly to the north is a smallhold- safeguard land for this use. ing area off Crooked Lane, in a messy area of urban fringe uses, which could accommodate 14.23 A romany museum was previously 10 pitches. -

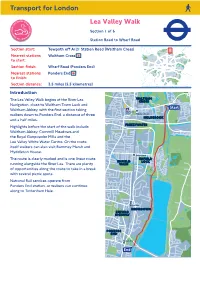

Lea-Valley-Section-1.Pdf

Transport for London.. Lea Valley Walk. Section 1 of 6. Station Road to Wharf Road. Section start: Towpath off A121 Station Road (Waltham Cross). Nearest stations Waltham Cross . to start: Section finish: Wharf Road (Ponders End). Nearest stations Ponders End . to finish: Section distance: 3.5 miles (5.5 kilometres). Introduction. The Lea Valley Walk begins at the River Lea Navigation, close to Waltham Town Lock and Waltham Abbey, with the first section taking walkers down to Ponders End, a distance of three and a half miles. Highlights before the start of the walk include Waltham Abbey, Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills and the Lee Valley White Water Centre. On the route itself walkers can also visit Rammey Marsh and Myddleton House. The route is clearly marked and is one linear route running alongside the River Lea. There are plenty of opportunities along the route to take in a break with several picnic spots. National Rail services operate from Ponders End station, or walkers can continue along to Tottenham Hale. Continues on next page Directions. From Waltham Cross station turn right out of the station, up the steps and right onto Eleanor Cross Road. After half a mile - on your left - you pass the entrance to the new Lee Valley White Water Centre (built for the London 2012 Olympics). Continue on the main road and shortly after the traffic lights turn right onto the towpath which can be found just before Station Road becomes Highbridge Street. To reach the town of Waltham Abbey continue along Highbridge Street. Here you can visit Waltham Abbey church (approximately 10 minutes walk away), Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills. -

Residential Property with Development Potential Picks Farm, Sewardstone Road, London, E4 7RA

Residential Property with Development Potential Picks Farm, Sewardstone Road, London, E4 7RA For Sale by Informal Tender Red line for identification purposes only. g 4 bedroom detached farm house g Equestrian facilities g Converted Barn providing 3 holiday lets g 2 x fishing lakes covering approximately 0.858 ha (2.118 acres) g Barn with a historic planning permission for a further g Whole Site extends to approximately 10.983 ha (27.14 acres) 2 holiday lets g Freehold interest g 4 further Agricultural outbuildings g Paddock extending to approximately 0.08 ha (0.198 acres) Offers in Excess of £2,000,000 Savills Chelmsford Savills Loughton 136 New London Rd The Triangle, 1A Smart’s Ln Chelmsford CM2 0RG Loughton IG10 4BU 01245 293241 020 8498 6600 savills.co.uk Location The site is located on the eastern side of The site benefits from being approximately The farmhouse extends to 163.4 sq m A112 which links Gilwell Hill to the south with 19 miles to the south of Stansted Airport and (1,759 sq ft) and benefits from excellent Sewardstone to the north. It is approximately 10 miles to the north of London City Airport. views to the front and rear. It has a kitchen, 1.46 miles north of Chingford Rail Station dining room and two spacious reception that provides direct links into London Description rooms on the ground floor, as well as Liverpool Street, with Loughton tube station The site comprises a substantial four four bedrooms on the first floor. It also 4 miles away. bedroom residential farm house, a barn has a historic planning permission for an extension. -

“Peelers Progress”

“PEELERS PROGRESS” Policing Waltham Abbey since 1840 by Bryn Elliott Foreword The police in Waltham Abbey are not a unique band of men and women in themselves. The station buildings occupied by the police in the locality were never structures considered in the forefront of architectural style. Although there were a few well known cases, no mind shattering, world famous crimes were ever said to have taken place in the area, and yet...... Here is a story of one relatively insignificant police station situated for 160 years on the outer edges of the Metropolitan Police District. It may be a surprise to learn that from the pages of this story that some well known cases were indeed enacted within its jurisdiction, and that the officers serving there were, on occasion, embroiled in famous events outside of the town. In writing this history of Waltham Abbey police officers, and the buildings in which they served, I have attempted to refrain from setting down the whole history of local law and order. Brief mention is made of the arrangement in force prior to the arrival of the Metropolitan Police in the area, hopefully in context. Other than those few instances I have avoided the period that would inevitably include such well known figures as the highwaymen Dick Turpin and the Gregory Gang, who included large swathes of Epping Forest in their plundering forays. Highwaymen have strong connections with the area during the 18th Century, but this is primarily the story of the modern police and the locality they served. It is unfortunate that few of the 19th Century local historians thought fit to make more than a passing mention of their local police force. -

London Effluent Reuse SRO July 2021

Strategic regional water resource solutions: Preliminary feasibility assessment Gate One Submission for: London Effluent Reuse SRO July 2021 i Contents 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Solution Description ........................................................................................................ 3 3 Outline Project Plan ......................................................................................................... 5 4 Technical Information ..................................................................................................... 9 5 Environmental and Drinking Water Quality Considerations................................................ 13 6 Initial Outline of Procurement and Operation Strategy ..................................................... 17 7 Planning Considerations ................................................................................................ 20 8 Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................................... 22 9 Key Risks and Mitigation Measures .................................................................................. 24 10 Option Cost/Benefits Comparison .................................................................................... 28 11 Impacts on Current Plan ................................................................................................. 32 12 Board Statement and Assurance .................................................................................... -

Land at Luther's Farm, Sewardstone, Essex Heritage Statement

Land at Luther’s Farm, Sewardstone, Essex Heritage Statement Land at Luther’s Farm, Sewardstone, Essex Heritage Statement Clients: Dr K. Misra Report no.: BSA 1829_1a Author: Ben Stephenson th Date: 15 August 2018 Final Version: E: [email protected] T: 01235 536754 Web:www.bsaheritage.co.uk 7 Spring Gardens, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 1AZ. This report, all illustrations and other associated material remains the property of BSA Heritage until paid for in full. Copyright and intellectual property rights remain with BSA Heritage. Contents Section 1: Introduction and Methodology ................................................................................................ 1 Section 2: Policy Context ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 3: Identified Heritage .................................................................................................................. 5 Section 4: Documentary Sources ........................................................................................................... 7 Section 5: Appraisal of Site and Environs ............................................................................................... 9 Section 6: Impact of Proposals ............................................................................................................. 10 Section 7: References and Sources ..................................................................................................... 12 ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Lea Valley Road, Chingford, London E4 7PX Tel 0203 393 4730 [email protected]

Lea Valley Road, Chingford, London E4 7PX Tel 0203 393 4730 [email protected] www.kgsc.org.uk Welcome to King George Sailing Club. Like all clubs and associations KGSC members gain most from club membership by making an active contribution to the functioning of the Club. You will get the most out of the club by being involved in its operation and get to know other Members for go faster sailing tips and assistance! We are run by members for members. The Club is not a commercial one and does not offer a service. In applying for membership you are agreeing to comply with all Club Rules including the completion of the required number of duties or to pay the avoidance fee. DATA PROTECTION The information which you provide in this form and any other information obtained or provided during the course of your application for membership or renewal will be used solely for the purpose of processing your application or renewal (including payment processing) and dealing with you as a member of King George Sailing Club. The data will not be shared with any third party for marketing or commercial purposes without firstly obtaining your explicit consent. THIS FORM IS FOR CASH OR CHEQUE PAYMENTS ONLY. (To pay by PayPal, please apply on-line at www.kgsc.org.uk ) Please complete the form below and return it with the correct fee (cheques payable to King George V Reservoir Sailing Club Ltd) to: Membership Secretary, KGSC, Lea Valley Road, Chingford, London, E47PX Membership Application Form from 1st April 2016 until 31st March 2017 Name Surname Address Home Tel Mobile Email Post Code Emergency contact name and number Occupation Vehicle details Make and model Registration number 1st Vehicle 2nd vehicle Craft Details Class Sail / hull number Colour Dinghy 1 Dinghy 2 Dinghy 3 Windsurfer 1 Windsurfer 2 Paddle Board Kayak Marketing: If new member(s) application.