“Peelers Progress”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

36 Highbridge Street, Waltham Abbey

36 HIGHBRIDGE STREET, WALTHAM ABBEY Flood Risk Assessment and Surface Water Drainage Statement Alcomax (Investments) Ltd SLR Ref: 408-07833-00001 Version No: 5 October 2018 36 Highbridge Street, Waltham Abbey : FRA and SWDS Filename: 181017_408-07833-00001_36HSWA_FRA_v5 SLR Ref No: 408-07833-00001 October 2018 BASIS OF REPORT This document has been prepared by SLR Consulting Limited with reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the manpower, timescales and resources devoted to it by agreement with Alcomax (Investments) Ltd. (the Client) as part or all of the services it has been appointed by the Client to carry out. It is subject to the terms and conditions of that appointment. SLR shall not be liable for the use of or reliance on any information, advice, recommendations and opinions in this document for any purpose by any person other than the Client. Reliance may be granted to a third party only in the event that SLR and the third party have executed a reliance agreement or collateral warranty. Information reported herein may be based on the interpretation of public domain data collected by SLR, and/or information supplied by the Client and/or its other advisors and associates. These data have been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. The copyright and intellectual property in all drawings, reports, specifications, bills of quantities, calculations and other information set out in this report remain vested in SLR unless the terms of appointment state otherwise. This document may contain information of a specialised and/or highly technical nature and the Client is advised to seek clarification on any elements which may be unclear to it. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Read, Simon ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2380-5130 (2017) Cinderella River: The evolving narrative of the River Lee. http://hydrocitizenship.com, London, pp. 1-163. [Book] Published version (with publisher’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23299/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Local Plan Respresentations

29 January 2018 bc Local Plan Regulation 19 Representation Planning Policy Team Epping Forest District Council Civic Offices Ben Thomas 323 High Street Epping Essex CM16 4BZ 33 Margaret Street London W1G 0JD T: +44 (0) 20 7499 8644 savills.com Epping Forest District Council Submission Version Local Plan We write on behalf of Crest Nicholson in relation to the site known as the former Pickfield Nursery at Pick Hill, Waltham Abbey (SLAA Reference SR-0161). Flawed / Absent Local Plan site selection process to-date: Pickfield Nursery was submitted to EFDC in response to the Call for Sites consultation in 2008 and has subsequently been promoted through the current Local Plan process since its inception in 2012. EFDC’s July 2012 SLAA referred to Pickfield Nursery as site SR-0161 but incorrectly identified it as a duplicate site with a much larger parcel (SLAA Reference SR-0020). Representations were then submitted in October 2012 highlighting this mistake. However, despite the submission of detailed representations and subsequent regular liaison with EFDC’s officers (including a positive formal pre-application meeting), EFDC’s Site Selection evidence base published in 2016 discounted Pickfield Nursery prior to Stage 1 of the selection process, once again incorrectly considering it as a duplicate site. Pickfield Nursery was finally acknowledged as an individual site in the Local Plan evidence base in the “Sites for consideration following Regulation 18 consultation” list published in July 2017. However, at the time of writing these representations (26th January 2018, one working day before the Pre-Submission consultation deadline) an assessment of these sites has still not been undertaken and Appendix C1 of the Report on Site Selection (December 2017) has not been completed. -

A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE NEW ZEALAND HORSE CAROLYN JEAN MINCHAM 2008 E.J. Brock, ‘Traducer’ from New Zealand Country Journal.4:1 (1880). A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse A Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Carolyn Jean Mincham 2008 i Abstract Both in the present and the past, horses have a strong presence in New Zealand society and culture. The country’s temperate climate and colonial environment allowed horses to flourish and accordingly became accessible to a wide range of people. Horses acted as an agent of colonisation for their role in shaping the landscape and fostering relationships between coloniser and colonised. Imported horses and the traditions associated with them, served to maintain a cultural link between Great Britain and her colony, a characteristic that continued well into the twentieth century. Not all of these transplanted readily to the colonial frontier and so they were modified to suit the land and its people. There are a number of horses that have meaning to this country. The journey horse, sport horse, work horse, warhorse, wild horse, pony and Māori horse have all contributed to the creation of ideas about community and nationhood. How these horses are represented in history, literature and imagery reveal much of the attitudes, values, aspirations and anxieties of the times. -

Evaluating the Risk of Non-Point Source Pollution From

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11(1), 601613, 2007 Evaluating the risk of non-point source pollution from biosolids: integrated modelling of nutrient losses at field and catchment scales www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/11/601/2007 © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. Evaluating the risk of non-point source pollution from biosolids: integrated modelling of nutrient losses at field and catchment scales P.G. Whitehead1, A.L. Heathwaite2, N.J. Flynn1, A.J. Wade1 and P.F. Quinn3 1Aquatic Environments Research Centre, Department of Geography, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6AB, UK 2Centre for Sustainable Water Management, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK 3Department of Civil Engineering, University of Newcastle, NewcastleUK Email for corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract A semi-distributed model, INCA, has been developed to determine the fate and distribution of nutrients in terrestrial and aquatic systems. The model simulates nitrogen and phosphorus processes in soils, groundwaters and river systems and can be applied in a semi-distributed manner at a range of scales. In this study, the model has been applied at field to sub-catchment to whole catchment scale to evaluate the behaviour of biosolid-derived losses of P in agricultural systems. It is shown that process-based models such as INCA, applied at a wide range of scales, reproduce field and catchment behaviour satisfactorily. The INCA model can also be used to generate generic information for risk assessment. By adjusting three key variables: biosolid application rates, the hydrological connectivity of the catchment and the initial P-status of the soils within the model, a matrix of P loss rates can be generated to evaluate the behaviour of the model and, hence, of the catchment system. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

Waltham Abbey Conservation Area

WALTHAM ABBEY CONSERVATION AREA 17 17 1 1 22 22 23 23 Drain 12 12 FB Playground HAROLD CRESCENT 109 Drain 105 11 11 21.3m 2 96 96 95 Drain 1 1 El Sub Sta 92 92 TCB HEREWARD CLOSE 1 1 93 Drain CROOKED MILE 90 90 91 7 7 AAbbebbey Fish Ponds 6 6 5 5 The Water 80 80 Tower 76 76 1 3 MILE CLOSE CS 74 74 MILE 6 6 5 5 CROOKED PARKLANDS Drain Drain MILE 64 64 Drain CROOKED 43 2b 2b 6 6 Drain The Lodge 2a 2a 6 6 20.4m PARKLANDS ABBEYVIEW 37 Subway Drain 19 17 Drain Drain St Clement's Harold's Bridge Court (restored) 26 58 58 to to 4 4 5 5 Drain MARGARET 13 FLAGSTAFF ROAD 13 Path CLOSE 10 10 Drain 9 Sluice 52 9 Drain 50 1 1 18 18 8 8 Cornmill Stream Car Parks Old River Lea or Lee 15 15 El Sub Sta 12 Community CANNON MEWS Centre Drain 1 to 4 Riverview 2 2 4 4 Drain Drain SAXON WAY 2 5 5 3 Path 3 1 1 7 to 10 Track 44 30 6 POWDERMILL LANE Ward Bdy 11 to 16 ABBEYVIEW 1 POWDERMILL MEWS 1 17 CR 19 4 4 23 23 1 1 14 25 TO 39 21 23 Gatehouse 32 12 27 31 17 17 33 CROOKED MILE 11 18 25 47 57 29 to 51 41 Path (um) 35 49 Moore House 61 55 to Moat 9 9 53 to 11 11 45 15 15 39 13 13 13 13 Abbey Gardens 22 6363 7 to l0 67 65 FB 69 PLANTAGANET PLACE 11 7 15 Weirs 14 25 25 Fn FB 13 13 Weir 9 9 12 5 5 Sluice 7 79 83 10 3 1 Posts 3 3 1 1 The Rectory 81 85 TCB Moat Highbridge 10 Court Abbey Gardens Ho PH ROMELAND 12 10 se se u u o o H H h h t t i i Ed Ed 8a 8 Stone 12 12 o o t t 1 1 NORTH PLACE 2 11 11 to to 8 1 1 2a 2a 6 10 4 16 14 The Abbey Church FB 8 8 o o t t 2 2 28 2 20 of Waltham Holy Cross 19.8m and St Lawrence Bank 30 19.2m Drain 19 36 13 13 15 15 5a 5a 1 1 -

An Assessment of the Feasibility of Annual Monitoring of Winter Gull Roosts in the UK and Possible Outputs from Such a Scheme

BTO Research Report No. 483 An assessment of the feasibility of annual monitoring of winter gull roosts in the UK and possible outputs from such a scheme Authors N.H.K. Burton, I.M.D. Maclean & G.E. Austin Report of work carried out by The British Trust for Ornithology under contract to Natural England November 2007 British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures .........................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................7 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................9 2. METHODS............................................................................................................................11 2.1 Identification of Sites Where Gull Numbers Surpass 1% Thresholds or Exceed 20,000 Birds ...........................................................................................................................11 2.2 Comparison of Species’ Indices Produced Using Wings and Webs Core Counts and Their Representativeness..............................................................................................12 -

Time and the New Police in Britain

The official response to Sidney Street Chris A. Williams Overview • Context: army interventions, 1890-1914 • Tottenham Outrage 1909 • Houndsdtich Murders Dec 1910 • Guns • Sidney Street –Raid –Course of seige • Outcomes Military ‘aid to the civil power’ • 1890 -1914 incidents in UK when the army opened fire: –1893 Featherstone – 2 dead –1907 Belfast – 2 dead –1911 Llanelli – 2 dead –1911 Liverpool – 0 dead –1911 Sidney Street – 2 dead –1914 Dublin – 3 dead Tottenham Outrage Jan 23 1909 • 2 gunmen rob wage delivery • 3 hour chase, including hijacked tram • 1 police officer, 1 member of public shot dead • Both robbers kill themselves as alternative to arrest/death. • Chaotic chase: police borrow guns from public • Review of Metropolitan Police firearms begins Houndsditch murders, Dec 16th 1910 • Gang (working shifts) disturbed by City of London Police • Sgt Bentley, PC Choate and Sgt Tucker killed • Gardstein mortally wounded: taken by gang to Grove St house where he dies • Dec 17th Doctor informs DI Wensley; discovers corpse; Wensley enters room • Met and City following up Grove St evidence and at least three informers Guns • 1903 Pistols Act: largely revenue-raising • Guns used: – Dreyse automatic – fatal shots at Houndsditch – Mauser C96 (402 foot pounds) – powerful but inaccurate at range – Webley Mk 1 .455 revolver (250 foot pounds) – Met – ‘Morris tube’ rifle – intended for training – City Police – Lee Enfield .303 (2,400 foot pounds) – Scots Guards Sidney St View from north Scots Guards at south cordon Churchill observing The burning -

Lea-Valley-Section-1.Pdf

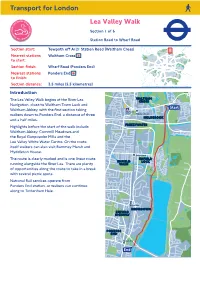

Transport for London.. Lea Valley Walk. Section 1 of 6. Station Road to Wharf Road. Section start: Towpath off A121 Station Road (Waltham Cross). Nearest stations Waltham Cross . to start: Section finish: Wharf Road (Ponders End). Nearest stations Ponders End . to finish: Section distance: 3.5 miles (5.5 kilometres). Introduction. The Lea Valley Walk begins at the River Lea Navigation, close to Waltham Town Lock and Waltham Abbey, with the first section taking walkers down to Ponders End, a distance of three and a half miles. Highlights before the start of the walk include Waltham Abbey, Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills and the Lee Valley White Water Centre. On the route itself walkers can also visit Rammey Marsh and Myddleton House. The route is clearly marked and is one linear route running alongside the River Lea. There are plenty of opportunities along the route to take in a break with several picnic spots. National Rail services operate from Ponders End station, or walkers can continue along to Tottenham Hale. Continues on next page Directions. From Waltham Cross station turn right out of the station, up the steps and right onto Eleanor Cross Road. After half a mile - on your left - you pass the entrance to the new Lee Valley White Water Centre (built for the London 2012 Olympics). Continue on the main road and shortly after the traffic lights turn right onto the towpath which can be found just before Station Road becomes Highbridge Street. To reach the town of Waltham Abbey continue along Highbridge Street. Here you can visit Waltham Abbey church (approximately 10 minutes walk away), Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills. -

Liberal Home Secretary Winston Churchill and the Siege of Sydney Street (1911)

LIBERAL HOME SECRETARY WINSTON CHURCHILL AND THE SIEGE OF SYDNEY STREET (1911) STORY OF A CONTROVERSY Student: Samira SNOUSSI Lecturer: Michael PARSONS – THE LIBERAL PARTY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………3 The Tottenham Outrage and the Houndsditch Murders………………………………………..4 The Siege Of Sydney Street……………………………………………………………………..6 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...14 2 INTRODUCTION Everyone, who has got the least knowledge, knows who is Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, who played such a major role during World War II that he was – and still is – considered as a hero in the United Kingdom, and at least in all European countries. To say a few words about his political path, he entered politics in 1900 as a Conservative member of parliament for Oldham. He switched parties in 1904 to become a Liberal, as he disagreed with the Conservative policy of protectionist tariffs preferentially favouring trade with the British Empire. As a Liberal, he had a rapid ascent, as he held major positions such as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, President of the Board of Trade, Home secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Minister of Munitions, Secretary of state for War, then for Air, then for the Colonies. He ended up rejoining the Conservative Party again in 1925 and became Chancellor of the Exchequer, and later on, in 1939, Prime Minister to play ‘the role of his life’. All of this can be found in the first article or book about Winston Churchill, of course. Yet, what is really