The Navigation of the River Lee (1190 – 1790)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

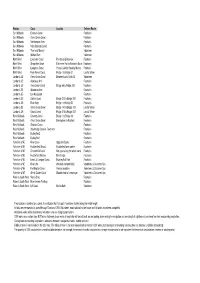

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

Copy of 2019 OSV Works V2

Region Canal Location Delivery Route East Midlands Erewash Canal Fountains East Midlands Grand Union Canal Fountains East Midlands Northampton Arm Fountains East Midlands Notts Beestob Canal Fountains East Midlands Trent and Mersey Volunteers East Midlands Welford Arm Volunteers North West Lancaster Canal Preston to Bilsborrow Fountains North West Shropshire Union Ellesmere Port to Nantwich Basin Fountains North West Llangollen Canal Poveys Lock to Swanley Marina Fountains North West Peak Forest Canal Bridge 1 to Bridge 37 Land & Water London & SE Grand Union Canal Between Locks 63 to 73 Volunteers London & SE Aylesbury Arm Fountains London & SE Grandunion Canal Bridge 68 to Bridge 209 Fountains London & SE Wendover Arm Fountains London & SE Lee Navigation Fountains London & SE Oxford Canal Bridge 215 to Bridge 242 Fountains London & SE River Stort Bridge 1 to Bridge 52 Fountains London & SE Grand Union Canal Bridge 140 to Bridge 181 Land & Water London & SE Oxford Canal Bridge 215 to Bridge 242 Land & Water West Midlands Coventry Canal Bridge 1 to Bridge 48 Fountains West Midlands Grand Union Canal Birmingham to Radford Fountains West Midlands Stratford Canal Fountains West Midlands Stourbridge Canal & Town Arm Fountains West Midlands Dudley No.2 Fountains West Midlands Dudley No.1 Fountains Yorkshire & NE River Ouse Opposite Docks Fountains Yorkshire & NE Huddersfield Broad Hudderfield town centre Fountains Yorkshire & NE Chesterfield Canal Hot spots along the whole canal Fountains Yorkshire & NE Hudderfield Narrow Milnsbridge Fountains -

Lea Valley Walk Section 5 (Three Mills to Limehouse Basin)

Lea Valley Walk To reach the start from Bromley-by-Bow station (District Line): Turn Section 5 (Three Mills to Limehouse Basin) left out of the station and at once go under the underpass and come up to pavement level on the far side of the main road. Go right to walk north, then Version 3 : July 2011 turn right down Three Mill Lane. Directions: Having come up the towpath ramp onto Three Mill Lane, turn left to cross the canal, and then turn right down another towpath ramp. There was a mill here in Saxon times, in fact at one stage four mills were Start: Three Mills (TQ382828) here, driven by sea and river water which came up the Lea at high tide. The clock tower dates from about 1750. The mills produced flour until the mid Station: Bromley-by-Bow 1700’s, after which the owners became involved in the manufacture of gin, Finish: Limehouse Basin (TQ362807) calling themselves “millers and malt distillers”. The House Mill is open to visitors on Sunday afternoons in summer (admission fee). The former Station: Limehouse DLR Station Victorian bottling plant (at the far end of the cobbled street) is now a film studio, the first “Big Brother” set was alongside to the east. Distance: 2 miles (3.2 km) Join the towpath again, this time on the other side of the canal. Water is on both sides of the towpath. Go under the London-Southend railway bridge Introduction: Three Mills to Limehouse Basin became Section 5 of the Lea and pass the closed footbridge which crosses over the tidal River Lea to the Valley Walk in July 2011. -

36 Highbridge Street, Waltham Abbey

36 HIGHBRIDGE STREET, WALTHAM ABBEY Flood Risk Assessment and Surface Water Drainage Statement Alcomax (Investments) Ltd SLR Ref: 408-07833-00001 Version No: 5 October 2018 36 Highbridge Street, Waltham Abbey : FRA and SWDS Filename: 181017_408-07833-00001_36HSWA_FRA_v5 SLR Ref No: 408-07833-00001 October 2018 BASIS OF REPORT This document has been prepared by SLR Consulting Limited with reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the manpower, timescales and resources devoted to it by agreement with Alcomax (Investments) Ltd. (the Client) as part or all of the services it has been appointed by the Client to carry out. It is subject to the terms and conditions of that appointment. SLR shall not be liable for the use of or reliance on any information, advice, recommendations and opinions in this document for any purpose by any person other than the Client. Reliance may be granted to a third party only in the event that SLR and the third party have executed a reliance agreement or collateral warranty. Information reported herein may be based on the interpretation of public domain data collected by SLR, and/or information supplied by the Client and/or its other advisors and associates. These data have been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. The copyright and intellectual property in all drawings, reports, specifications, bills of quantities, calculations and other information set out in this report remain vested in SLR unless the terms of appointment state otherwise. This document may contain information of a specialised and/or highly technical nature and the Client is advised to seek clarification on any elements which may be unclear to it. -

The Lea Valley Walk

THE LEA VALLEY WALK LEAGRAVE TO THE HEART OF LONDON by Leigh Hatts JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk 774 Lea Valley text 2020 3rd Ed Rpt.indd 3 28/09/2020 14:52 © Leigh Hatts 2015 Third edition 2015 ISBN 978 1 85284 774 6 Reprinted 2020 (with updates) Second edition 2007 First edition 2001 Printed in Singapore by KHL using responsibly sourced paper. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey® with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright 2015. All rights reserved. Licence number PU100012932. Updates to this Guide While every effort is made by our authors to ensure the accuracy of guidebooks as they go to print, changes can occur during the lifetime of an edition. Any updates that we know of for this guide will be on the Cicerone website (www.cicerone.co.uk/774/updates), so please check before planning your trip. We also advise that you check information about such things as transport, accommodation and shops locally. Even rights of way can be altered over time. We are always grateful for information about any discrepancies between a guidebook and the facts on the ground, sent by email to [email protected] or by post to Cicerone, Juniper House, Murley Moss, Oxenholme Road, Kendal, LA9 7RL. Register your book: To sign up to receive free updates, special offers and GPX files where available, register your book at www.cicerone.co.uk. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Read, Simon ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2380-5130 (2017) Cinderella River: The evolving narrative of the River Lee. http://hydrocitizenship.com, London, pp. 1-163. [Book] Published version (with publisher’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23299/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject These articles are published every fortnight in Hackney Today newspaper. They are usually on p.25. They can be downloaded from the Hackney Council website at http://www.hackney.gov.uk/w-hackneytoday.htm. Articles prior to no.158 are not available online. Issue Publication Subject Topic no. date 207 11.05.09 125-130 Shoreditch High Street Architecture: Business 303 25.03.13 4% Industrial Dwellings Company Social Care: Jewish Housing 357 22.06.15 50 years of Hackney Archives Research 183 12.05.08 85 Broadway in Postcards Research Methods 146 06.11.06 Abney Park Cemetery Open Spaces 312 12.08.13 Abney Park Cemetery Registers Local History: Records 236 19.07.10 Abney Park chapel Architecture: Ecclesiastical 349 23.02.15 Activating the Archive Local Activism: Publications 212 20.07.09 Air Flight in Hackney Leisure: Air 158 07.05.07 Alfred Braddock, Photographer Business: Photography 347 26.01.15 Allen's Estate, Bethune Road Architecture: Domestic 288 13.08.12 Amateur sport in Hackney Leisure: Sport 227 08.03.10 Anna Letitia Barbauld, 1743-1825 Literature: Poet 216 21.09.09 Anna Sewell, 1820-1878 Literature: Novelist 294 05.11.12 Anti-Racism March Anti-Racism 366 02.11.15 Anti-University of East London Radicalism: 1960s 265 03.10.11 Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Females, 1851 Social Care 252 21.03.11 Ayah's Home: 1857-1940s Social Care: Immigrants 208 25.05.09 Barber's Barn 1: John Okey, 1650s Commonwealth and Restoration 209 08.06.09 Barber's Barn 2: 16th to early 19th Century Architecture: -

How Do You Lose a River?

Number 1,1, SpringSummer 2016 2015 Waypoints 1 How do you lose a river? In this paper I explore the concept of the lost river and the implications this Jonathan Gardner term has for our understanding of the history of changing urban environ- jonathan.gardner@ucl. ments. ac.uk In taking a voyage down one of the London 2012 Olympic Park’s now-filled waterways, the Pudding Mill River, charting it and the surrounding area’s diverse history, I explore how rivers end up becoming losable. Drawing on diverse methodologies from archaeology and geography and with a particular emphasis on mapping, I argue that a literal and metaphorical exploration of such a rapidly changing environment reveals a multitude of buried narratives and fluid histories. This research suggests that the labeling of a river as lost is not a politically neutral act and that, with its romantic connotations, the term may actually serve to legitimise insensitive and contentious changes to our environment. Much has been written about London’s numerous lost watercourses over the years, most notably Nicho- las Barton’s seminal volume The Lost Rivers of London [1] and more, recently Paul Talling’s London’s Lost Riv- ers [2] and Tom Bolton’s London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide [3]. In addition to these works a large range of blogs and websites devoted to the lost rivers are continually created and updated, for example, Diamond Geezer 2015 [4]. The subject is one that seems to inspire intense interest amongst a wide range of people and would suggest that city-dwellers are curiously attracted to such forgotten or lost spaces, and in particular, the unusual juxtaposition of the natural and the urban these watercourses seem to present. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

Hackney Wellbeing Walks

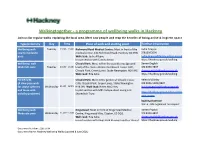

Walkingtogether - a programme of wellbeing walks in Hackney Join us for regular walks exploring the local area. Meet new people and reap the benefits of being active & in green space Type/intensity Day Time Place of walk and starting point Further information Wellbeing walk Tuesday 13.00 - 13.40 Richmond Road Medical Centre: Meet in front of the Sadie Alleyne Low to moderate medical centre, 136 Richmond Road, Hackney E8 3HN. 07815993599 pace Walk lead: Sadie Alleyne [email protected] In partnership with Family Action https://hackney.gov.uk/walking Wellbeing walk Clissold Park: Meet within the outside area (ground Darren English Moderate pace Tuesday 13.00 - 14.00 level) of the main entrance to Clissold House Café, 020 8356 4897 Clissold Park, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington, N16 9HJ. [email protected] Walk lead: Rita Saha https://hackney.gov.uk/walking Fit 4 Health Clissold Park: Meet in the garden of Clissold House Helen McGinley (A slow pace walk Cafe, Clissold Park, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington, 020 8356 5285/4897 for stroke sufferers Wednesday 11.30 - 12.15 N16 9HJ. Walk lead: Helen McGinley [email protected] and those with In partnership with MRS Independent Living and https://hackney.gov.uk/after-stroke- mobility problems) Shoreditch Trust. programme Booking essential Dial -a -ride organised on request Wellbeing walk Kingsmead: Meet in front of Kingsmead Medical Darren English Moderate pace Wednesday 11.00 – 12.00 Centre, Kingsmead Way, Clapton, E9 5QG. 020 8356 4897 Walk lead: Rita Saha. [email protected]