Western Cumberland County Comprehensive Plan Consortium Joint Municipal Comprehensive Plan Cumberland County, Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simultaneous Cabinet Further Transformation In

6 SIMULTANEOUS CABINET Monday 13 November 2017 FURTHER TRANSFORMATION IN EAST SUFFOLK (REP1629) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Suffolk Coastal District Council and Waveney District Council agreed in January 2017 to create a new Council for east Suffolk. This was preceded by an intensive period of public consultation in November 2016, the results of which demonstrated that the majority of residents were in favour of one district Council in east Suffolk. 2. The decision to create a new Council for east Suffolk was both ambitious and ground breaking. A “super district” Council will be formed which will be the largest in England in terms of population. The creation of a new Council follows the successful legacy of both Councils working closely together for many years. Officers of all levels of seniority are shared, a joint Business Plan has been adopted and other key policies such as the Housing Strategy are shared. The Councils already share one website under the “East Suffolk” banner and Councillors from both authorities have attended meetings of each Council’s Cabinets since 2010. Cabinet portfolios are aligned and members have shared representation on various outside bodies. 3. The creation of a new Council will be a model other authorities follow as they decide how best to grapple with the significant challenges facing local government. Councils need to be of a scale large enough to face these challenges by having a loud enough voice, a strong bargaining position, a healthy balance sheet and a resilient workforce, yet small enough to feel connected to their residents. The creation of the new Council for east Suffolk will strike that balance. -

List of Councils in England by Type

List of councils in England by type There are a total of 353 councils in England: Metropolitan districts (36) London boroughs (32) plus the City of London Unitary authorities (55) plus the Isles of Scilly County councils (27) District councils (201) Metropolitan districts (36) 1. Barnsley Borough Council 19. Rochdale Borough Council 2. Birmingham City Council 20. Rotherham Borough Council 3. Bolton Borough Council 21. South Tyneside Borough Council 4. Bradford City Council 22. Salford City Council 5. Bury Borough Council 23. Sandwell Borough Council 6. Calderdale Borough Council 24. Sefton Borough Council 7. Coventry City Council 25. Sheffield City Council 8. Doncaster Borough Council 26. Solihull Borough Council 9. Dudley Borough Council 27. St Helens Borough Council 10. Gateshead Borough Council 28. Stockport Borough Council 11. Kirklees Borough Council 29. Sunderland City Council 12. Knowsley Borough Council 30. Tameside Borough Council 13. Leeds City Council 31. Trafford Borough Council 14. Liverpool City Council 32. Wakefield City Council 15. Manchester City Council 33. Walsall Borough Council 16. North Tyneside Borough Council 34. Wigan Borough Council 17. Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 35. Wirral Borough Council 18. Oldham Borough Council 36. Wolverhampton City Council London boroughs (32) 1. Barking and Dagenham 17. Hounslow 2. Barnet 18. Islington 3. Bexley 19. Kensington and Chelsea 4. Brent 20. Kingston upon Thames 5. Bromley 21. Lambeth 6. Camden 22. Lewisham 7. Croydon 23. Merton 8. Ealing 24. Newham 9. Enfield 25. Redbridge 10. Greenwich 26. Richmond upon Thames 11. Hackney 27. Southwark 12. Hammersmith and Fulham 28. Sutton 13. Haringey 29. Tower Hamlets 14. -

![Written Evidence Submitted by East Sussex County Council [ASC 021]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0523/written-evidence-submitted-by-east-sussex-county-council-asc-021-280523.webp)

Written Evidence Submitted by East Sussex County Council [ASC 021]

Written evidence submitted by East Sussex County Council [ASC 021] • How has Covid-19 changed the landscape for long-term funding reform of the adult social care sector? The challenges facing the adult social care market prior to the pandemic are well documented and, in many cases, have been brought into sharp focus over the last 12 months. Local Authority published rates; contract arrangements (e.g. block arrangements); commissioning approaches (e.g. strategic partners) and CCG funding agreements including Better Care Fund allocations are all key funding reform considerations which sit alongside the necessity to offer choice, personalised care and high quality, safe services. Residential and nursing care There are 306 registered care homes in East Sussex – the majority are small independently run homes, which don’t have the wrap-around organisational infrastructure enjoyed by larger / national providers. In East Sussex, Local Authority placements are made across around one-third of the residential and nursing care market. At the peak of the second wave over 100 care homes in East Sussex were closed to admissions due to Covid outbreaks. Week commencing 04/01/21 there were 853 confirmed cases of Covid19 in East Sussex care home settings. During 2021, as of the week ending 19/03/2021, East Sussex has had 2,404 deaths registered in total and 1,110 of these have been attributable to COVID-19, of which 597 have occurred in hospital and 436 have occurred in care homes (LG reform data). In the two years up to April 2019, there were 26 residential and nursing home closures in East Sussex resulting in a loss of 435 beds, across all care groups. -

IPPR | Empowering Counties: Unlocking County Devolution Deals ABOUT the AUTHORS

REPORT EMPOWERING COUNTIES UNLOCKING COUNTY DEVOLUTION DEALS Ed Cox and Jack Hunter November 2015 © IPPR 2015 Institute for Public Policy Research ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive thinktank. We are an independent charitable organisation with more than 40 staff members, paid interns and visiting fellows. Our main office is in London, with IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated thinktank for the North of England, operating out of offices in Newcastle and Manchester. The purpose of our work is to conduct and publish the results of research into and promote public education in the economic, social and political sciences, and in science and technology, including the effect of moral, social, political and scientific factors on public policy and on the living standards of all sections of the community. IPPR 4th Floor 14 Buckingham Street London WC2N 6DF T: +44 (0)20 7470 6100 E: [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This paper was first published in November 2015. © 2015 The contents and opinions in this paper are the authors ’ only. POSITIVE IDEAS for CHANGE CONTENTS Summary ............................................................................................................3 1. Devolution unleashed .....................................................................................9 2. Why devolve to counties? ............................................................................11 2.1 Counties and their economic opportunities ................................................... -

985 EDUCATION (2) That the Revised Estimates Of

985 EDUCATION (Note: This report was presented to the Council at its meeting on \2th Decem ber, 1952.) EDUCATION COMMITTEE: 4th December, 1952. Present: Councillors Brown (in the Chair), Adkins, Alien, J.P., Bailey, A. C. L. Bishop, Buckle, Collins, Duff, Gange, J.P., Leigh, J.P., C.C., Lovell, MacRae, Mason, Mrs. Milner and Sheldrake (Representative members); Messrs. F. W. Coppin and C. A. Lillingston, Rev. H. Eland Stewart, and Miss D. E. Hunt (Co-opted members); Mr. J. Barrow, C.C. (Appointed member); Mr. J. Rostron, Miss A. Robinson and Miss D. E. Ross (Members of the Youth Sub-Committee). PART I.—RECOMMENDATIONS. RECOMMENDATION I: Education Estimates of Capital Expenditure for the Year 1953/54. Your Committee has considered, and is in agreement with, recommendation I of the report of its General Purposes and Finance Sub-Committee of 4th December, 1952, relating to capital expenditure for the financial year 1953/54, details of which are set out in paragraph 61 (2nd December, 1952) of the report of the (Education) Sites and Buildings Sub-Committee. Resolved to RECOMMEND: That a resolution in the following terms be passed by the Council: That the items included in the estimates of capital expenditure, amounting to £52,365, for the financial year 1953/54, in accordance with the details now submitted, be approved and submitted to the Middlesex County Council. RECOMMENDATION II: Education Estimates on Revenue Account for the Years 1952/53 and 1953/54. Your Committee has considered, and is in agreement with, recommendation II of the report of its General Purposes and Finance Sub-Committee of 4th December, 1952, relating to the approval of estimates of income and expendi ture on revenue account for the financial year 1953/54, and revised estimates for 1952/53. -

Freight Rail B

FREIGHT RAIL B Pennsylvania has 57 freight railroads covering 5127 miles across the state, ranking it 4th largest rail network by mileage in the U.S. By 2035, 246 million tons of freight is expected to pass through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, an increase of 22 percent over 2007 levels. Pennsylvania’s railroad freight demand continues to exceed current infrastructure. Railroad traffic is steadily returning to near- World War II levels, before highways were built to facilitate widespread movement of goods by truck. Rail projects that could be undertaken to address the Commonwealth’s infrastructure needs total more than $280 million. Annual state-of-good-repair track and bridge expenditures for all railroad classes within the Commonwealth are projected to be approximately $560 million. Class I railroads which are the largest railroad companies are poised to cover their own financial needs, while smaller railroads are not affluent enough and some need assistance to continue service to rural areas of the state. BACKGROUND A number of benefits result from using rail freight to move goods throughout the U.S. particularly on longer routes: congestion mitigation, air quality improvement, enhancement of transportation safety, reduction of truck traffic on highways, and economic development. Railroads also remain the safest and most cost efficient mode for transporting hazardous materials, coal, industrial raw materials, and large quantities of goods. Since the mid-1800s, rail transportation has been the centerpiece of industrial production and energy movement. Specifically, in light of the events of September 11, 2001 and from a national security point of view, railroads are one of the best ways to produce a more secure system for transportation of dangerous or hazardous products. -

Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bridgend County Borough Council Caerphilly County Borough Council the City of Cardiff Counc

Welsh Local Authorities gritting information (alphabetical order) Blaenau Gwent Info and map of http://www.blaenau-gwent.gov.uk/resident/highways- County Borough gritting routes cleansing/winter-gritting/winter-gritting-routes-salt-bins/ Council http://www.blaenau- gwent.gov.uk/resident/emergencies-crime- prevention/preparing-for-winter/ Bridgend County Info and map of http://www.bridgend.gov.uk/winter.aspx Borough Council gritting routes http://www.bridgend.gov.uk/services/highways.aspx Caerphilly County Info and map of http://www.caerphilly.gov.uk/Services/Roads-and- Borough Council gritting routes pavements/Gritting-and-snow-clearing/Winter-Service- Plan http://www.news.wales/south/caerphilly-county- borough-council/caerphilly-council-is-monitoring- weather-conditions-2017-01-25740.html The City of Cardiff Info and map of https://www.cardiff.gov.uk/ENG/resident/Parking-roads- Council gritting routes and-travel/Winter-maintenance/Pages/Winter- Location of salt maintenance.aspx bins https://www.cardiff.gov.uk/ENG/resident/Community- safety/Severe-winter- weather/Documents/winter%20weather%20guide.pdf Carmarthenshire Info and map of http://www.carmarthenshire.gov.wales/home/residents/t County Council gritting routes ravel-roads-parking/gritting/#.WH4UVk1DT9Q Twitter https://twitter.com/CarmsCouncil/status/7992671481998 25409 Ceredigion County Info and map of https://www.ceredigion.gov.uk/English/Resident/Travel- Council gritting routes Roads-Parking/Highways-During- Twitter Winter/Pages/default.aspx https://www.ceredigion.gov.uk/English/Resident/Travel- -

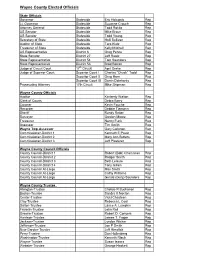

List of Elected Officials

Wayne County Elected Officials State Officials Governor Statewide Eric Holcomb Rep Lt. Governor Statewide Suzanne Crouch Rep Attorney General Statewide Todd Rokita Rep US Senator Statewide Mike Braun Rep US Senator Statewide Todd Young Rep Secretary of State Statewide Holli Sullivan Rep Auditor of State Statewide Tera Klutz Rep Treasurer of State Statewide Kelly Mitchell Rep US Representative District 6 Greg Pence Rep State Senator District 27 Jeff Raatz Rep State Representative District 54 Tom Saunders Rep State Representative District 56 Brad Barrett Rep Judge of Circuit Court 17th Circuit April Drake Rep Judge of Superior Court Superior Court I Charles “Chuck” Todd Rep Superior Court II Greg Horn Rep Superior Court III Darrin Dolehanty Rep Prosecuting Attorney 17th Circuit Mike Shipman Rep Wayne County Officials Auditor Kimberly Walton Rep Clerk of Courts Debra Berry Rep Coroner Kevin Fouche Rep Recorder Debbie Tiemann Rep Sheriff Randy Retter Rep Surveyor Gordon Moore Rep Treasurer Nancy Funk Rep Assessor Tim Smith Rep Wayne Twp-Assessor Gary Callahan Rep Commissioner-District 1 Kenneth E Paust Rep Commissioner-District 2 Mary Ann Butters Rep Commissioner-District 3 Jeff Plasterer Rep Wayne County Council Officials County Council-District 1 Robert (Bob) Chamness Rep County Council-District 2 Rodger Smith Rep County Council-District 3 Beth Leisure Rep County Council-District 4 Tony Gillam Rep County Council At-Large Max Smith Rep County Council At-Large Cathy Williams Rep County Council At-Large Gerald (Gary) Saunders Rep Wayne County Trustee Abington-Trustee Chelsie R Buchanan Rep Boston-Trustee Sandra K Nocton Rep Center-Trustee Vicki Chasteen Rep Clay-Trustee Rebecca L Cool Rep Dalton-Trustee Lance A. -

Harrisburg Division

HARRISBURG DIVISION NORTHERN REGION TIMETABLE NUMBER 1 EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 19, 2015 COMMITTED TO SAFETY DOUBLE ZEROS ZERO INJURIES ZERO INCIDENTS HARRISBURG DIVISION TIMETABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Timetable General Information..................................................5 a. Train Dispatcher Contact Information…………………….4 b. Station Page........................................................................5 c. Explanation of Characters.................................................5 d. Diesel Unit Groups.............................................................6 e. Main Track Control.............................................................6 f. Division Special Instructions.............................................6 II. Harrisburg Division Station Pages.....................................7-263 III. Harrisburg Division Special Instructions......................265-269 NORFOLK SOUTHERN DIVISION HEADQUARTERS Train Dispatching Office 4600 Deer Path Road Harrisburg, PA 17110 Assistant Superintendent – Microwave 541-2146 Bell 717-541-2146 Dispatch Chief Dispatcher Microwave 541-2158 Bell 717-541-2158 Harrisburg East Dispatcher Microwave 541-2136 Bell 717-541-2136 Harrisburg Terminal Dispatcher Microwave 541-2138 Bell 717-541-2138 Lehigh Line Dispatcher Microwave 541-2139 Bell 717-541-2139 Southern Tier Dispatcher Microwave 541-2144 Bell 717-541-2144 Mainline Dispatcher Microwave 541-2142 Bell 717-541-2142 D&H Dispatcher Microwave 541-2143 Bell 717-541-2143 EMERGENCY 911 HARRISBURG DIVISION TIMETABLE GENERAL INFORMATION A. -

Caerphilly County Borough Council by Email Only [email protected] Dear Councillor Poole

Our ref: NB Ask for: Communications 01656 641150 Date: 7 September 2020 Communications @ombudsman-wales.org.uk Councillor David Poole Council Leader Caerphilly County Borough Council By Email Only [email protected] Dear Councillor Poole Annual Letter 2019/20 I am pleased to provide you with the Annual letter (2019/20) for Caerphilly County Borough Council. I write this at an unprecedented time for public services in Wales and those that use them. Most of the data in this correspondence relates to the period before the rapid escalation in Covid-19 spread and before restrictions on economic and social activity had been introduced. However, I am only too aware of the impact the pandemic continues to have on us all. I am delighted to report that, during the past financial year, we had to intervene in (uphold, settle or resolve early) a smaller proportion of complaints about public bodies: 20% compared to 24% last year. We also referred a smaller proportion of Code of Conduct complaints to a Standards Committee or the Adjudication Panel for Wales: 2% compared to 3% last year. With regard to new complaints relating to Local Authorities, the overall number has decreased by 2.4% compared to the previous financial year. I am also glad that we had to intervene in a smaller proportion of the cases closed (13% compared to 15% last year). That said, I am concerned that complaint handling persists as one of the main subjects of our complaints again this year. Amongst the main highlights of the year, in 2019 the National Assembly for Wales (now Senedd Cymru Welsh Parliament) passed our new Act. -

THE SANITARY FUNCTIONS of COUNTY COUNCILS. General

428 MTDICBALPJTURAL I SANITARY FUNCTIONS OF COUNTY COUNCILS. [FEB. 23, 1895. traces. Then, again, the line between giving IIa faint opal- Reports under the Housing of the'.Working Classes escence," " giving a very slight precipitate," and " giving no Aet. precipitate," is very difficult to draw, especially when no Applications and questions under the Isolation Hos- strength is given for the solutions nor limit of time for the pitals Act. formation ot a precipitate. It would be a very lengthy task Appeals by parish councils in case of default in sani- indeed to point out these defects in detail, but a comparison tary matters on the part of the rural district council. of the British with other more modern Pharmacopceias will 3. Whether any county medical officer of health had been soon show how much more minute are the instructions given appointed. for testing in these latter. In the first place fourteen administrative counties, accord- To these and similar criticisms from a manufacturer's ing to the returns furnished by the respective clerks, have standpoint there are two objections that are likely to be appointed county medical officers of health. These pioneer taken: first, that they are mere details which it is the counties are: business of the manufacturer to attend to; and, secondly, Bedfordshire Lancasllire Surrey that an absolute standard of should be Cheshire London Worcestershire purity set up and Derbyshire Northumberland Yorkshire, N. Riding adlhered to at any cost. To the first objection it may fairly be Durham Shropshire Yorkslhire, -

Planning Context

1. Preface This plan serves as the update to Chapter 12, the transportation plan element, of the 2003 Cumberland County Comprehensive Plan. Background information and specific statistics on the modes of transportation in the county can be found in Chapter 11 of the comprehensive plan and in the Harrisburg Area Transportation Study (HATS) Long Range Transportation Plan1. 2. Introduction Cumberland County is home to a variety of transportation resources ranging from interstate highways to sidewalks in local neighborhoods. The transportation infrastructure found in the county supports the national, state and local economies and the high quality of life in our communities, alike. The value of our transportation system warrants the county’s involvement in its planning, design, construction and maintenance. Cumberland County’s transportation planning authority emanates from Article III of the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code (MPC), Act 247 of 1968. The MPC requires county comprehensive plans to include a plan for the “movement of people and goods” that includes all modes of transportation. Under this planning authorization the county’s actual role in planning and implementing improvements for all modes of transportation must be carefully managed. This plan identifies the salient transportation issues and needs facing the county and recommends a series of county-based strategies and action steps aimed at addressing the identified needs and issues. 3. Highways and Bridges Issues and Needs Cumberland County has an extensively developed highway network that provides for local, regional, and national transportation. All roads in the county are owned and maintained by municipalities, the state, or the federal government. The rich hydrologic resources of Cumberland County are spanned by 438 bridges that are over 20’ in length2.