Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Proposal on Melka Wakena Hydropower Project

Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology Civil and Environmental Engineering Department Optimal Reservoir operations on water resource projects at Wabi Shebelle river basin A thesis submitted and presented to the school of graduate studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Masters of Science in Civil Engineering (Major Hydraulics Engineering) By Amir Abdulhamid Advisor Dr.Ing. Dereje Hailu Addis Ababa University Ethiopia October, 2017 2017 Declaration and copy right I, Amir Abdulhamid Kiyar, declare that this is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for similar or any degree award. _____________________________ Signature ______________________________ Date This dissertation is a copyright material protected under the Berne Convention, the Copy right Act, 1999 and other international and national enactments in the behalf, on the intellectual property. It may not be produced by any means in full or in part, except for short extracts in fair dealing, for research or private study, Critical scholarly review or disclosure with an acknowledgement, without written permission of the School of Graduate Studies, on the behalf of both the author and the Addis Ababa University. i 2017 Acknowledgement I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my major advisor, Dr.Ing. Dereje Hailu for his close friendship, professional assistance, genuine and valuable criticism all the way from the outset to the completion of the study. I would like to thank all staffs in the Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy especially to those staffs in the Departments of Hydrology and GIS, National Metrological Agency and Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation, for providing me with related materials. -

Risk-Taking.Pdf

Authors: Abdi Umar (UN OCHA Pastoralist Communication Iniatiative) with Bob Baulch (Institute of Development Studies, UK) Editors: Patta Scott-Villiers and Ruth Tanner Design: Giant Arc Design Layout: Sarah Wilson Printing: United Printers, Addis Ababa Published by the UN OCHA Pastoralist Communication Initiative P.O. Box 27068 Addis Ababa Code 1000, Ethiopia Telephone: +251 (0) 115 444420 Email: [email protected] March 2007 Any parts of this report may be copied, reproduced or adapted to meet local needs without permission, provided that the parts reproduced are distributed free or at cost, not for profit. For any reproduction with commercial ends, permission must first be obtained from the publisher. The publisher would appreciate being sent a copy of any materials in which text from the publication has been used. © The UN OCHA Pastoralist Communication Initiative, 2007 If you would like any further information on the UN OCHA Pastoralist Communication Initiative or additional copies of this report, please contact UN OCHA-PCI at the above address. The opinions expressed in this paper are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations, the Institute of Development Studies or the UK Department for International Development. Front cover photo: Elise Ganem Contents Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 7 1 Background and Method 10 1.1 Methods used in the Trade and Marketing Study 11 2 Pastoralist Commerce, Routes and Commodities 15 2.1 Historical trade in Somali speaking Horn of Africa 16 2.2 The environment in Somali -

Urban Institutional and Infrastructure Development Program

DOCUMENT OF THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report no: PAD123029-ET PROGRAM APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON PROPOSED IDA CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR89.2 MILLION (US$127 MILLION EQUIVALENT), IDA GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 191.7 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized (US$273 MILLION EQUIVALENT), AND SCALE UP FACILITY CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF US$200 MILLION TO THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR AN URBAN INSTITUTIONAL AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM February 21, 2018 Social, Urban, Rural, and Resilience Global Practice Africa This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 31, 2017) Currency Unit = Ethiopian Birr (ETB) ETB 27.40 = US$1 US$1.42413 = SDR 1 Currency US$1 FISCAL YEAR July 8 – July 7 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD French Development Agency (Agence Française de Développement) AMP Asset Management Plan APA Annual Performance Assessment APACRC Annual Performance Assessment Complaints Resolution Committee APAG Annual Performance Assessment Guidelines BoFED Bureau of Finance and Economic Development (Regional) BUD Bureau of Urban Development (part of regional governments) CIP Capital Investment Plan CPA Country Procurement Assessment CPF Country Partnership Framework CPS Country Partnership Strategy CSA Central Statistics Agency -

Prevalence and Molecular Characterisation of Eimeria Species in Ethiopian Village Chickens

Prevalence and molecular characterisation of Eimeria species in Ethiopian village chickens Luu et al. Luu et al. BMC Veterinary Research 2013, 9:208 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/9/208 Luu et al. BMC Veterinary Research 2013, 9:208 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/9/208 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and molecular characterisation of Eimeria species in Ethiopian village chickens Lisa Luu1, Judy Bettridge1,2, Robert M Christley1*, Kasech Melese3, Damer Blake4, Tadelle Dessie2, Paul Wigley1, Takele T Desta2,5, Olivier Hanotte5, Pete Kaiser6, Zelalem G Terfa7, Marisol Collins1 and Stacey E Lynch1,2 Abstract Background: Coccidiosis, caused by species of the apicomplexan parasite Eimeria, is a major disease of chickens. Eimeria species are present world-wide, and are ubiquitous under intensive farming methods. However, prevalence of Eimeria species is not uniform across production systems. In developing countries such as Ethiopia, a high proportion of chicken production occurs on rural smallholdings (i.e. ‘village chicken production’) where infectious diseases constrain productivity and surveillance is low. Coccidiosis is reported to be prevalent in these areas. However, a reliance on oocyst morphology to determine the infecting species may impede accurate diagnosis. Here, we used cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to investigate the prevalence of Eimeria oocyst shedding at two rural sites in the Ethiopian highlands. Results: Faecal samples were collected from 767 randomly selected chickens in May or October 2011. In addition, 110 chickens were sampled in both May and October. Eimeria oocysts were detected microscopically in 427 (56%, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 52-59%) of the 767 faecal samples tested. -

Memoire Jalalanbmax

ODA Innovation and collective action in farmer- managed irrigation schemes a first-rank resource to land and water scarcity Study case of the Burka Jalala irrigation scheme in East Hararghe, Ethiopia. Thesis presented by : Céline ALLAVERDIAN Director : Pascale MAÏZI-MOITY (CNEARC) Supervisor : Jean-Philippe FONTENELLE (GRET) Jury : ENGUEHARD François (GRET) FONTENELLE Jean-Philippe (GRET) GUILLAUME Julie (GRET) LANAU Sylvain (CNEARC) MAÏZI-MOITY Pascale (CNEARC) Montpellier, February, 15th 2007 “Bishaanif haati hamtu hinqabdu…” “Water and one’s mother badness does not have…” Oromo proverb 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT First, I would like to thank all the people of Burka Jalala for their generosity: to all the women and children who greeted me and opened their hearts to me during my stay, to all the farmers which gave their time and shared their knowledge with me. I especially thank my dear sister Kimiya, my grandmother Fatumeh Sadico, my favorite shop keepers Abdulla and Jamal, my favorite wise man Umar Abdullai for his charisma and sense of humor, the “good crazy man” for his simple joy, the development agents Tesfaye and Ahmed “ tafki ” for their friendliness and help, my bodyguard and step-father Aliyi Ibroo, and many more… I give a huge “ galaatomi ” at Mohamed Gelmo from ODA to have untiringly helped us in all our difficulties. Thank you for your welcome, your friendship, your honesty, our discussions and many laughs. Thanks to Awad as all the ODA staff. Another big “ galootomi ” to Abdallah Ibroo, Umar and his sisters for their precious support during our stay in Jarso, as well as Abdu Karim from the Agricultural Bureau for his rightness and kindness, and his colleagues from OIDA for their support. -

L Μ E P ‰ Z Më ¦ M E G E L E T a O R O M I A

Waggaa 21ffaa... Lak. 9/2005 Finfinnee, Adoolessa 7/2005 1 9 ፳ ኛ ዓመት...... ቁጥር /፪ሺ፭ Ö¿Ö}ð፣NUK? 7 d¿ 2g=፭ 21st year ......... No. 9/2013 Finfine, July 14, 2013 MAGALATA OROMIYAA L µ E p ‰ Z Më ¦ M E G E L E T A O R O M I A Gatiin Tokkoo ..... Qar. __ To’annoo Caffee Mootummaa Naannoo Lak. S. Poostaa ........ 21383-1000 Oromiyaatiin Kan Bahe ¦¿«è ”¶ ....___ ብር ከ __ ሣንቲም £Þ.Q.e¼Y ........... l‰ZMë¦ wN?^© ŒGF”í L¿·Rr P.O.Box .................. Unit Price ............ Birr ___ uÚô *aT>Á ºmf}r £’» QABIYYEE T¨<Ý CONTENT Labsii Lak. 183/2005 ›ªÏ lØ` ፩፻፹፫/፪g=፭ Proclamation No. 183/2013 Labsii Dabalata Baajata Hojiiwwan ¾፪g=፭ ¯.U ¾}ÚT] u˃ ›ªÏ K*aT>Á Supplementary Budget Proclamation For Mootummaa Naannoo Oromiyaa Bara wN?^© ¡ML© S”ÓYƒ Y^ዎ ‹ ¾¨Ë Oromia Regional State Services 2005 EFY 2005tiif Labsame .......................... Fuula 1 }ÚT] u˃ ›ªÏ .....................................ገጽ ፩ .....................................................page 1 ›ªÏ lØ` ፩፻፹፫/፪g=፭ Labsii Lak. 183/2005 ¾፪g=፭ ¯.U. ¾}ÚT] u˃ ›ªÏ Proclamation No. 183/2013 Labsii Dabalata Baajataa Hojiiwwan K*aT>Á wN?^© ¡ML© S”ÓYƒ Y^ዎ ‹ Supplimentary Budget Proclamation Mootummaa Naannoo Oromiyaa Bara ¾¨Ë }ÚT] u˃ ›ªÏ for 2005 EFY Oromia National 2005tiif Labsame Regional State Services K፪g=፭ u˃ ¯Sƒ u*aT>Á ¡MM ¨<eØ Bara Baajataa 2005tti hojiiwwanii fi ta- WHEREAS, it is necessary to adopt and KT>Ÿ“¨’<ƒ Y^ዎ ‹ “ ›ÑMÓKA„‹ jaajilawwan Naannoo Oromiyaa Keessatti implement the supplement budgetary ap- adeemsifamaniif baajanni barbaachisaa ¾T>ÁeðMѨ<” }ÚT] u˃ ›êÉq Y^ propriation which is required for the pur- ta’e raggaasifamee hojiirra ooluun waan Là SªK< ›eðLÑ> uSJ’<' poses and services of Oromia region for irra jiruuf; the 2005 (E.C) fiscal year; }hhKA u¨×¨< ¾*aT>Á wN?^© ¡ML© Akkaataa Heera Mootummaa Naannoo NOW, THEREFORE, in accordance with Oromiyaa Fooyya’ee Bahe Labsii Lak. -

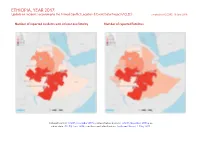

ETHIOPIA, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

ETHIOPIA, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 ETHIOPIA, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Riots/protests 177 18 68 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 157 130 903 Development of conflict incidents from 2008 to 2017 2 Violence against civilians 138 95 430 Strategic developments 21 0 0 Methodology 3 Remote violence 7 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 501 243 1401 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from 2008 to 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 ETHIOPIA, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known. Erroneous location data, especially due to identical place names, cannot The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event be fully excluded. -

Exploring New Political Alternatives for the Oromo in Ethiopia

CMIREPORT Exploring New Political Alternatives for the Oromo in Ethiopia Report from Oromo workshop and its after-effects Edited by Siegfried Pausewang R 2009: 6 Exploring New Political Alternatives for the Oromo in Ethiopia Report from Oromo workshop and its after-effects Edited by Siegfried Pausewang R 2009: 6 CMI Reports This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 Printed version: ISSN 0805-505X Electronic version: ISSN 1890-503X Printed version: ISBN 978-82-8062-341-6 Electronic version: ISBN 978-82-8062-342-3 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Indexing terms Ethiopia Oromo Democracy Local administration Ethiopian federation Project number 24065 Project title Oromo politics seminar CMI REPORT EXPLORING NEW POLITICAL ALTERNATIVES FOR THE OROMO R 2009: 6 Contents Abbreviationss v Ethiopian words vi The Oromo between past and future 1 Introduction 1 Siegfried Pausewang Part I: The Bergen Meeting From Haile-Selassie to Meles: Government, people and the nationalities question in Ethiopia 14 Christiopher Clapham Challenges and prospects for the Oromo in Ethiopia 20 David H. Shinn Oromo nationalism, and the continuous multi-faceted attack on the Oromo cultural, civic and political organisations 26 Mohammed Hassen Ethiopia since the Derg: Democratic pretension and performance. 40 Lovise Aalen Democracy and human rights – not for the Oromo? Structural reasons for the -

Local History of Ethiopia Giabassire - Gipril © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia Giabassire - Gipril © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) Gi.., cf Ji.. Gia.. (Italian-derived), see Ja.. HCD47 Giabassire, see Jabasire JCT24 Giadabele, see Jadabele HER22 Giadebac, see Jadebak JBK61 Giadunlei, see Jadunley JCM55 Giaffaie, see Jaffaye HED38 Giagada, see Jagada & HEK26 JDB97 Giaggia, see Jajja JDJ80 Giagiaba, see Jajaba HEL35 Giaguala, see Jagwala HEJ89 Giagui, see Jagwi JDD85 Giah, see Jah HEB45 Giaio, see Jayo HDG89 Gialdessa, see Jaldessa & HDH49 HDH83 ?? Gialdu, see Jaldu GCU15 Giale, see Jale & HDD48 JDH39 Giallenco, see Chelenko HDE57 Giallo, see Jallo & HDH62 JDC41 JDC72 HEF43 Gialo Caie, see Jalo Kaye HCR25 Gialo, see Jalo JDB91c Gialo, see Jallo HCK49c Giam Giam, see Jam Jam JCT52 Giam Ialin, see Jam Yalin GCM42 Giamciar, see Jamchar HDT03 Giammafit, see Jammafit HCH31 Giamo (Giamu), see Jomu HFC06 Gian Berchi, see Jan Berki JC... Gianagobo, see Janagobo JDK51 Gianasse, see Jeneseney HED41 Gianchemer, see Jankemer HEC83 Gianchit Mariam, see Jankit Maryam HER06 Giancuc, see Jankuk HER05 Giancue, see Jankew HEJ67 Gianda, see Janda HCS70c Giangero, see Janjero HDG45 Giangiassa, see Janjasa HDR06 Giangimen, see Janjimen JBR82 Giapto, see Chaptu GCU55 Giara, see Jara & HCG73 HDB39 HCE11 Giari Bule, see Jeri Bule HDJ26 Giarra, see Jarra & HDU67 JDC47 Giarra Giarti, see Jarra Jarti HEF43 Giarre Teo, see Jarre Tew HEF43 Giarretis, see Jarretis JDJ47 Giarsagoro, see Jarsagoro, cf Ejersa Goro HBS80 Giarso, see Jarso & HDG19 HDG45 HDJ09 HDJ29 HDJ95 Giarti, see Jarti JCG36 Giarti (spring) 06/40 [MS WO] HCG54 Giaruca, see Jaruka HDS55 Giasanbat, see Yesenbet HCD54 Giascia, see Jasha HCR25 Giato, see Jalo HDD55 Giattagobi, see Jattagobi HDJ14 Giaue (Gioie), see Jawe Published online by the Nordic Africa Institute library | nai.uu.se/library 1 of 18 Local History of Ethiopia Giabassire - Gipril © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) Gib.., see also Jib. -

University Free State Universiteit Vrystaat

University Free State 1111111IIIII II'" IIIII 11III 11III 11III 11II1 II1I1 II1III11I1 I1II1 1III1 II1I1 II1II11I 34300002279622 Universiteit Vrystaat ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF LAND USE: THE CASE OF EAST HARARGHE ADMINISTRATIVE ZONE IN ETHIOPIA BY Rassen Ibrahim Worseme Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Philosophia Doctor (Ph.D.) degree Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Department of Agricultural Economics University of The Free State . •. 'J . Promoter: Prof. M.F. Viljoen Co-promoter: Prof. J.A. Groenewald Bloemfontein, Republic of South Africa February 2004 ,__ w__ , ,--,~~ , lfn.lvOTOH:eH V{;l'n tU~ ~ OTcnJe-Vry~toot BltnMPONTEJN 6 - JUL 2004 Declaration I declare that the thesis hereby submitted by me for the Philosophia Doctor (Ph.D.) degree at the University of The Free State is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me at another university/faculty. I furthermore cede copyright of the thesis in favour of the University of The Free State. Hassen Ibrahim Worseme CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF TABLES ~ ix LIST OF FIGURES xiv ABBREVIATIONS xv DEFINITION OF TERMS xvi ABSTRACT xvii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xix CHAPTER 1. THE RESEARCH PROBLEM 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Problem statement 3 1.3 Objectives of the study 4 1.4 Research, hypothesis 5 1.5 Importance of the research 5 1.6 Scope of the study 6 1.7 Arrangement ofthesis 7 CHAPTER 2. RESEARCH APPROACH ~ · 10 2.1 Introduction 10 2.2 Identifying research problem 11 2.3 Selecting a research area and stratification 12 2.4 Conducting literature study : 14 2.5 Determining the model to apply 15 2.6 Data collection 16 2.6.1 Developing questionnaire 16 2.6.2 Sample drawing 17 2.6.3 Conducting fieldwork 18 2.7 Data analysis 18 CHAPTER 3. -

Local History of Ethiopia : Eba Ledara

Local History of Ethiopia Eba Ledara - Elyas © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) E.., see also I.. eba (A) monkey, monkey's cry; eeba (O) type of blessing; ebba, sky-god of the Somali in former times JDN86 Eba Ledara (waterhole) 10/40 [Ne] ?? Ebala (hills in Sidamo), cf Abala ../.. [Mi] HCL54 Ebano, see Ibano HDP27 Ebantu, see Ibantu HFC97 Ebaro (area), cf Abaro 14/37 [WO] HEK16 Ebbenat (large market) 11/38 [Gu] HEK35 Ebbenat (Ebnet), see Ibnat HE... Ebbo sub-district (centre in 1964 = Bichie) 12/39 [Ad] ebelizi: eblis (O) devil, demon HEA45 Ebelizi 11°18'/35°12' 742 m 11/35 [WO Ch Gz] HBT.. Ebicha 05/38 [Mi] A feeder valley of the Aflata valley in Sidamo. HDS10 Ebieta Jesus, see Ebyeta Iyesus HCS33 Ebrama (mountain), see under Hosaina 07/37 [WO] Ebsana, Yebsana, name of an Arsi Oromo tribe JCN06c Ebsana 07/40 [Wa] HDP27 Ebu 10°10'/36°20' 1542 m 10/36 [Gz] ebyet: ibyet (ibyät) (T) magnificence HDS10 Ebyeta Iyesus (Ebieta Jesus) 10°06'/37°35' 1176 m 10/37 [+ WO Gz] JCL82 Ecal, see Ekal echa (O) /place:/ where; /question:/ from where? HFE76c Echa (Eccia) (mountain) 14/39 [+ Gu] HET07 Echelva, see Ekelva HD... Echerri (Etsherri) 09/37 [+ 18] HER79 Echimcha (Ecimcia) (hill) 13°19'/37°25' 2260 m 13/37 [Gz] HDB77 Econu, see Ekonu eda (A) female buffalo; (O) last night; ida (A,T) debt; cf Ali as first part of name JEB50 Eda Ali (area) 810 m 11/40 [WO] HFE62 Eda Giyorgis (Edda Giorgis) 14°08'/38°42' 14/38 [+ x] HFF72 Edaga Hamus (Eddaga H.), see Idaga Hamus HFD46c Edaga Hebret, see Idaga Hebret HF.. -

Sgicement EIA.Pdf

Environmental Impact Assessment; NCSC Cement Plant 2008 Environmental Impact Assessment Report National Cement Share Company Prepared by: Fitsum Consultancy Services December 2008 IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: This Environmental Impact Assessment Report was prepared by Fitsum Consultancy Services in 2008. It was prepared exclusively for the Ethiopian government authorities in relation to the application for all relevant environmental approvals prior to project development. Schulze Global Investments LLC (Ethiopia Branch) (“SGI ET”) has only inserted this ecover pag and a condensed table of contents (outlining relevant sections of the report) on page 2. Therefore, SGI ET makes no representation and disclaims all liability regarding the accuracy, reliability, depth, relevance, or sufficiency of the information included or omitted in this report. SGI ET disclaims liability for all previous, current, or subsequent conditions that may affect the report including but not limited to fraud, mistake, omission, ignorance, error, or change of conditions. Therefore, SGI ET is not liable for any loss or damage resulting from or relating in any way to the information presented in the report however it may be caused (including but not limited to negligence). 1 | Fitsum Consultancy Services Environmental Impact Assessment; NCSC Cement Plant 2008 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Report Outline (sections relevant to SGI’s Double Bottom Line Impact Report) TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................................................