SIPRI Yearbook 2001: Armaments, Disarmament and International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions (January 1993 - April 2020) Huntington BAE Spirit Booz Allen L3Harris Precision Rolls- Airbus Boeing CACI Perspecta General Dynamics GE Honeywell Leidos SAIC Leonardo Technologies Lockheed Martin Ingalls Northrop Grumman Castparts Safran Textron Thales Raytheon Technologies Systems Aerosystems Hamilton Industries Royce Airborne tactical DHPC Technologies L3Harris airport Kopter Group PFW Aerospace to Aviolinx Raytheon Unisys Federal Airport security Hydroid radio business to Hutchinson airborne tactical security businesses Vector Launch Otis & Carrier businesses BAE Systems Dynetics businesses to Leidos Controls & Data Premiair Aviation radios business Fiber Materials Maintenance to Shareholders Linndustries Services to Valsef United Raytheon MTM Robotics Next Century Leidos Health to Distributed Energy GERAC test lab and Technologies Inventory Locator Service to Shielding Specialities Jet Aviation Vienna PK AirFinance to ettain group Night Vision business Solutions business to TRC Base2 Solutions engineering to Sopemea 2 Alestis Aerospace to CAMP Systems International Hamble aerostructure to Elbit Systems Stormscope product eAircraft to Belcan 2 GDI Simulation to MBDA Deep3 Software Apollo and Athene Collins Psibernetix ElectroMechanical Aciturri Aeronautica business to Aernnova IMX Medical line to TransDigm J&L Fiber Services to 0 Knight Point Aerospace TruTrak Flight Systems ElectroMechanical Systems to Safran 0 Pristmatic Solutions Next Generation 911 to Management -

Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017

Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017 Appendix D: Securities Held by Funds The Four Funds hold thousands of publicly and privately traded securities. Act 44 directs the Four Funds to publish “a list of all publicly traded securities held by the public fund.” For consistency in presenting the data, a list of all holdings of the Four Funds is obtained from Pennsylvania Treasury Department. The list includes privately held securities. Some privately held securities lacked certain data fields to facilitate removal from the list. To avoid incomplete removal of privately held securities or erroneous removal of publicly traded securities from the list, the Four Funds have chosen to report all publicly and privately traded securities. The list below presents the securities held by the Four Funds as of June 30, 2017. 1345 AVENUE OF THE A 1 A3 144A AAREAL BANK AG ABRY MEZZANINE PARTNERS LP 1721 N FRONT STREET HOLDINGS AARON'S INC ABRY PARTNERS V LP 1-800-FLOWERS.COM INC AASET 2017-1 TRUST 1A C 144A ABRY PARTNERS VI L P 198 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP ABRY PARTNERS VII L P 1MDB GLOBAL INVESTMENTS L ABAXIS INC ABRY PARTNERS VIII LP REGS ABB CONCISE 6/16 TL ABRY SENIOR EQUITY II LP 1ST SOURCE CORP ABB LTD ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS II LP 200 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS IV LP 21ST CENTURY FOX AMERICA INC ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS V LP 21ST CENTURY ONCOLOGY 4/15 -

Foreign Investment in Indiana

Indiana Economic Development Corporation FOREIGN INVESTMENT IN INDIANA 1,027 TOTAL COMPANIES EACH UNIQUE FLAG IN A COUNTY REPRESENTS ONE OR MORE COMPANIES OF THE FOLLOWING ORIGIN 12 Australia 12 Austria 3 Belgium 13 Brazil 78 Canada 21 China 6 Denmark 6 Finland 52 France 127 Germany 4 Hong Kong 8 India 42 Ireland 8 Israel 36 Italy 315 Japan 1 Liechtenstein 25 Luxembourg 1 Malaysia 14 Mexico 29 Netherlands 5 New Zealand 5 Norway 1 Poland 3 Portugal 1 Qatar 1 Russia 4 Saudi Arabia 3 Singapore 2 South Africa 10 South Korea 15 Spain 31 Sweden 39 Switzerland 5 Taiwan 1 Thailand 1 Turkey 1 United Arab Emirates 95 United Kingdom INCLUDING JOINT VENTURES 1 Australia/Spain 1 Austria/Germany 1 Denmark/USA 1 Finland/Ireland INDIANA IN RELATION TO THE U.S. 2 France/Germany SEATTLE 2 Germany/Japan 1 CHICAGO NEW YORK Japan/Luxembourg INDIANAPOLIS ST. 1 LOS ANGELES Japan/Switzerland ATLANTA 5 DALLAS Japan/USA 1 Spain/USA 1 NORTH CAPITOL AVENUE, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46204 | 800.463.8081 | TEL 317.232.8800 | FAX 317.232.4146 | iedc.in.gov REV 6.20 Indiana Economic Development Corporation FOREIGN INVESTMENT IN INDIANA AUSTRALIA SWITZERLAND Sims Metal Management East Chicago Schneider Electric USA, Inc. Mishawaka Mulzer Crushed Stone Leavenworth GECOM Corp. Greensburg Leclanche Anderson Nipro Pharma Packaging Westport Pratt Paper, LLC Gary Air Liquide America LP Mount Vernon Americas Nestle USA Beverage Division Anderson Mulzer Crushed Stone Mauckport Hitachi Powdered Metals, Greensburg C&R Racing Indianapolis Hahn Systems New Haven Mulzer Crushed Stone Newburgh (USA) Inc. NTN Bearing Corporation of UBS Financial Services Anderson Cardno Indianapolis America Whitestown LafargeHolcim East Chicago Air Liquide America LP Pittsboro Seabrook Technology Group Pendleton Honda Manufacturing of Indiana Greensburg Delivra Indianapolis Geodis Logistics Plainfield Medtronic Plainfield LLC Kuri Tec Mfg. -

FORWARD Annual Report and Accounts 2001 >EQUIPPED >Being Prepared Is Everything

Smiths Group plc Annual report and accounts 2001 >FORWARD Annual report and accounts 2001 >EQUIPPED >Being prepared is everything. At Smiths we focus on the future. What will our customers want tomorrow? How can we exploit technology to provide enhanced solutions for their most demanding applications? How can we extend our capabilities to give them the service they need? We are constantly searching for ways to add value for our customers. This is how we generate profitable organic growth. >DISCOVERY >Discovery is about being always one step ahead. It is about meeting needs in ways that others haven’t yet thought of. It is about developing products that provide innovative solutions for the toughest applications. Through total commitment to research and development, Smiths seeks sustainable competitive advantage. >TEAMWORK >At Smiths we believe in teamwork. We work closely with our suppliers and customers to build productive partnerships and long-term relationships. Within the company, too, teamwork is essential. Not just working together day by day, but focusing everyone's efforts on maximum efficiency, productivity, flexibility and responsiveness. Through teamwork we seek to be a leader. >REACH >In a world where efficiency is paramount, customers want to deal with fewer, better suppliers. At Smiths we have the necessary size and diversity. We are global. Our products are wide-ranging. We have the reach to be our customers’ preferred supplier. 01 03 01 As a first-tier supplier working directly 03 We are a leading supplier of products used with prime manufacturers, we are during critical and intensive care procedures, delivering systems for front-line defence and for continuing care during recovery. -

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy, Chairman & CEO • ILFC Colin Stuart, Vice

SPEEDNEWS 20TH ANNUAL AVIATION INDUSTRY SUPPLIERS CONFERENCE Steven F. Udvar-Hazy, Chairman & CEO • ILFC Mr. Hazy, in 1973, founded Interlease Group, Inc., which today is known as International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC), with a portfolio valued at more than $40b, consisting of more than 800 jet aircraft. ILFC is the largest customer of Airbus and Boeing. ILFC went public in 1983 with $220 million in assets and $8 million in profit. In 1990, ILFC was acquired by American Intl. Group, and since the acquisition, ILFC has generated a cumulative profit of $8.3b for AIG. In 1966, while an undergraduate student at UCLA, he formed Airlines Systems Research Consultants, a firm specializing in airline routes, fleet and planning analysis. His first clients included Aer Lingus, Mexicana and Air New Zealand. He later graduated from UCLA in 1968 with a BS in Economics and a minor in Intl. Relations. Mr. Hazy also serves on the Board of Directors of Skywest, Inc., and is on the Board of several foundations, educational institutions and corporations, and is the major donor for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. He also has pilot type ratings in Gulfstreams, Learjets, Citations and presently is captain on the GV. Colin Stuart, Vice President-Marketing • Airbus Colin Stuart was appointed to his current position, VP-Marketing, in May 1996. His responsibilities include managing both the development and implementation of customer/product marketing activities and related marketing support services for the complete range of Airbus commercial products. He studied under the British Aerospace undergraduate apprenticeship scheme before obtaining a degree in aeronautical engineering from Bath University in 1966. -

The Defence Industry in the 21St Century

The Defence Industry in the 21st Century “With nine countries (and their collective industrial prowess) involved in its development, the F-35 repre- sents a new model of inter- national cooperation, ensuring affordable U.S. and coalition partner security well into the 21st century” – Sources: Photograph by US Department of Defense, Quote by Lockheed Martin Corporation Thinking Global … or thinking American? “With nine countries (and their collective industrial prowess) involved in its development, the F-35 represents a new model of international cooperation, ensuring affordable U.S. and coalition partner security well into the 21st century” – Sources: Photograph by US Department of Defense, Quote by Lockheed Martin Corporation Welcome The purpose of this paper is to provoke a debate. To stimulate further the dialogue we enjoy with our clients around the world. As the world’s largest professional services firm, PricewaterhouseCoopers works with clients in every segment of the defence industry – from the Americas to the whole of Europe; from the Middle East and Africa to Asia and the Pacific Rim. On many occasions, our discussions focus on the technical issues in which we are pre-eminently well-qualified to advise. Here, however, we seek to debate the issues that affect your industry. To review the factors that shaped today’s environment, to assess the implications for contractors and to look at the factors that might shape the future. Our views are set out in the following pages. We have debated some of these issues with some of our clients already but the time is right for a broader discus- sion. -

Europeantransatlanticarmscoope

ISB?: 960-8124-26-3 © 2003 Defence Analysis Institute 17, Valtetsiou Street 10680 Athens, Greece Tel.: (210) 3632902 Fax: (210) 3632634 web-site: www.iaa.gr e-mail: [email protected] Preface Introduction The European Defence Industrial Base and ESDP RESTRUCTURING OF THE EUROPEAN DEFENCE INDUSTRY THE INDUSTRY-LED RESTRUCTURING PROCESS. 1997-1999: the European defence industry under pressure 13 Firms seek economies of scale and enlargement of the market State/industry consensus on the need for industrial consolidation From international cooperation to transnational integration 18 The first cooperative programmes, common subsidiaries and joint ventures Privatisation Concentration Groups with diversified activities Appraisal by sector of activities 27 Defence aerospace and electronics: a strategy of segment consolidation The land and naval armaments sectors: an industrial scene divided along national lines Trends in European defence industrial direct employment 37 Overview Situation by country THE OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 41 The permanence of the Europe/United States imbalance 43 Unfavourable conditions... …in the face of the American strategy of expansion in Europe First initiatives aimed at creating a favourable environment for European defence industries 48 Creation of ad hoc structures by the principal armaments producing countries (Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain and Sweden) First steps towards an institutional strategy for the EU in the field of armaments ALL-UNION INITIATIVES, ENHANCED COOPERATION AND CONVERGENCE OBJECTIVES -

Copyrighted Material

1 Flight Control Systems 1.1 Introduction Flight controls have advanced considerably throughout the years. In the earliest biplanes flown by the pioneers flight control was achieved by warping wings and control surfaces by means of wires attached to the flying controls in the cockpit. Figure 1.1 clearly shows the multiplicity of rigging and control wires on an early monoplane. Such a means of exercising control was clearly rudimentary and usually barely adequate for the task in hand. The use of articulated flight control surfaces followed soon after but the use of wires and pulleys to connect the flight control surfaces to the pilot’s controls persisted for many years until advances in aircraft performance rendered the technique inadequate for all but the simplest aircraft. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Figure 1.1 Morane Saulnier Monoplane refuelling before the 1913 Aerial Derby (Courtesy of the Royal Aero Club) Aircraft Systems: Mechanical, electrical, and avionics subsystems integration. 3rd Edition Ian Moir and Allan Seabridge © 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 2 Flight Control Systems When top speeds advanced into the transonic region the need for more complex and more sophisticated methods became obvious. They were needed first for high-speed fighter aircraft and then with larger aircraft when jet propulsion became more widespread. The higher speeds resulted in higher loads on the flight control surfaces which made the aircraft very difficult to fly physically. The Spitfire experienced high control forces and a control reversal which was not initially understood. To overcome the higher loadings, powered surfaces began to be used with hydraulically powered actuators boosting the efforts of the pilot to reduce the physical effort required. -

Defence Diversification Revisited

Defence Diversification Revisited A history of defence diversification in the UK and elsewhere – lessons learned and ways forward. May 2016 Foreword by Len McCluskey, General Secretary of Unite Unite the Union represents tens of thousands of workers in the UK Defence industry. Our members work at the cutting edge of technology in highly skilled, high value jobs. Their contribution to the economy of the U.K. is vital and for many communities is essential for their survival. Defence is a complex industry with a world class supply chain, largely based onshore in the UK due to the security involved in the manufacturing process. The current UK footprint is responsible for globally recognised products and capabilities and presents a link with a proud heritage of manufacturing across the country. Iconic aircraft, ships, submarines and weapons have been produced by the UK across the decades and the country is still producing world class equipment such as the Queen Elizabeth class Carriers, Astute submarines, Typhoon fighter, Hawk trainer and Wildcat helicopters. Radar, sensors and weapons systems are also produced here in the UK and the industry generates billions of pounds in tax and national insurance payments as well as billions in exports. However, the defence industry has also suffered huge cuts in jobs in recent decades, with tens of thousands of workers being made redundant. There are further challenges facing the industry and Unite is calling for a new Defence Industrial Strategy allied to a broader Manufacturing Strategy to defend those jobs. A critical component could and should be an agency to identify potential job losses far enough in advance for a legally binding programme of diversification to kick in, retaining critical skills and finding new work for existing workers. -

Table 7A.2. the 100 Largest Arms-Producing Companies

Table 7A.2. The 100 largest arms-producing companies in the OECD and developing countries, 2000 Figures in columns 6, 7, 8 and 10 are in US$ million. Figures in italics are percentages. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 a Rank Arms sales Total sales Col. 6 as Profit Employment 2000 1999 Company (parent company) Country Sectorb 2000 1999 2000 % of col. 8 2000 2000 1 1 Lockheed Martin USA Ac El Mi 18 610 19 790 25 329 73 – 519 130 000 2 2 Boeing USA Ac El Mi 16 900 16 000 51 521 33 2 128 198 000 3 3 BAE SYSTEMS UK A Ac El Mi SA/A 14 400 15 470 18 473 78 1 440 84 900 Sh 4 4 Raytheon USA El Mi 10 100 11 530 16 895 60 141 93 700 5 5 Northrop Grumman USA Ac El Mi SA/A 6 660 7 070 7 618 87 608 39 300 6 6 General Dynamics USA El MV Sh 6 520 5 550 10 356 63 901 43 300 7 – EADSc France/ Ac El Mi 5 340 0 22 303 24 – 832 88 880 FRG/ Spain 8 7 Thalesd France El Mi SA/A 5 160 4 450 8 476 61 . 57 230 9 8 Litton USA El Sh 3 950 3 910 5 588 71 218 40 300 ARMS PRODUCTION357 10 13 TRW USA El Oth 3 370 2 990 17 231 20 438 102 880 11 9 United Technologies USA El Eng 2 880 3 480 26 583 11 1 808 153 800 12 14 Mitsubishi Heavy Industriese Japan Ac MV Mi Sh 2 850 2 460 28 255 10 – 189 . -

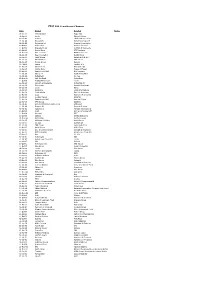

FTSE 100 Constituent History Updated

FTSE 100 Constituent Changes Date Added Deleted Notes 19-Jan-84 CJ Rothschild Eagle Star 02-Apr-84 Lonrho Magnet Sthrns. 02-Jul-84 Reuters Edinburgh Inv. Trust 02-Jul-84 Woolworths Barrat Development 19-Jul-84 Enterprise Oil Bowater Corporation 01-Oct-84 Willis Faber Wimpey (George) 01-Oct-84 Granada Group Scottish & Newcastle 01-Oct-84 Dowty Group MFI Furniture 04-Dec-84 Brit. Telecom Matthey Johnson 02-Jan-85 Dee Corporation Dowty Group 02-Jan-85 Argyll Group Berisford (S.& W.) 02-Jan-85 MFI Furniture RMC Group 02-Jan-85 Dixons Group Dalgety 01-Feb-85 Jaguar Hambro Life 01-Apr-85 Guinness (A) Enterprise Oil 01-Apr-85 Smiths Inds. House of Fraser 01-Apr-85 Ranks Hovis McD. MFI Furniture 01-Jul-85 Abbey Life Ranks Hovis McD. 01-Jul-85 Debenhams I.C. Gas 06-Aug-85 Bnk. Scotland Debenhams 01-Oct-85 Habitat Mothercare Lonrho 02-Jan-86 Scottish & Newcastle Rothschild (J) 08-Jan-86 Storehouse Habitat Mothercare 08-Jan-86 Lonrho B.H.S. 01-Apr-86 Wellcome EXCO International 01-Apr-86 Coats Viyella Sun Life Assurance 01-Apr-86 Lucas Harrisons & Crosfield 01-Apr-86 Cookson Group Ultramar 21-Apr-86 Ranks Hovis McD. Imperial Group 22-Apr-86 RMC Group Distillers 01-Jul-86 British Printing & Comms. Corp Abbey Life 01-Jul-86 Burmah Oil Bank of Scotland 01-Jul-86 Saatchi & S. Ferranti International 01-Oct-86 Bunzl Brit. & Commonwealth 01-Oct-86 Amstrad BICC 01-Oct-86 Unigate Smiths Industries 09-Dec-86 British Gas Northern Foods 02-Jan-87 Hillsdown Holdings Argyll Group 02-Jan-87 I.C. -

Anticipating Restructuring in the European Defense Industry

ANTICIPATING RESTRUCTURING IN THE EUROPEAN DEFENSE INDUSTRY A study coordinated by BIPE with contributions from: Wilke, Maack & Partners - Wmp Consult (Germany), The Centre for Defence Economics, York University (UK), Institute for Management of Innovation and Technology (Sweden) ZT Konsulting (Poland) Authors: Professor Ola Bergstrom, Mr. Frédéric Bruggeman, Mr. Jerzy Ganczewski, Professor Keith Hartley, Mr. Dominique Sellier, Dr. Elisabeth Waelbroeck-Rocha, Dr Peter Wilke, Professor Dr. Herbert Wulf The consultant takes full responsibility for the views and the opinion expressed in this report. The report does not necessarily reflects the views of the European Commission for whom it was prepared and by whom it was financed. European Defence Industry Anticipating Restructuring Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................9 II. DEVELOPMENT DURING THE PAST DECADE AND PRESENT INDUSTRY STRUCTURE ........................................11 1. Defining the defence industry............................................................................................................................... 11 2. Structure of the EU Defence Industry: the demand side.................................................................................... 12 2.1. Budgets................................................................................................................................................................