Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gowest Newsletter Fall 2020

September 2020 Volume 1, Issue 2 Welcome back WESTies!! INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dr. Stepany Rose 2-4 Words from our Faculty We have missed you, but hope each of you had a 5 EDI Corner & Matrix Center restful summer. While things will not be traditional as we continue to navigate a global pandemic, we 6 Interviews: Dean Vidler & are still tremendously excited for what is in store Jane Muller this academic year. 6 Queer Lives Matter I hope you have had the opportunity to meet our new faculty members—Dr. ‘Ilaheva Tua’one and 7 Disclosure & Advocacy Dr. Julie Torres. Both Dr. Tua’one and Dr. Torres 8 Scholarships & Local Creators bring refreshing and critical value to our program with their much-needed areas of expertise and 8 WEST Certificates fresh approaches to Women’s and Ethnic Studies. From practical activism to addressing contemporary social justice concerns to intersectional applied theoretical analyses, their presence marks a growing vision NEWSLETTER EDITORS for WEST. Read more about them in this issue, sign up for their courses, and welcome them into our campus and community. DR. TRE WENTLING While we are all adjusting to new routines and understandings of what is “normal,” IRINA AMOUZOU (‘22) please know that we are mindful of still providing the most robust academic opportunities for you. Several new models for course offerings are available— HyFlex, remote synchronous, remote asynchronous, and traditional online. The variety of modalities have been developed to protect the health and well-being of students, faculty and staff. While this may not seem ideal, know that we are all adjusting. -

A Love Letter to Black Mothers

BERGAMO KEYNOTE, 2019 A Love Letter to Black Mothers NICHOLE A. GUILLORY Kennesaw State University A Prelude. STAYED AWAY FROM THE BERGAMO CONFERENCE on Curriculum Theory and I Classroom Practice for nearly 20 years because I have always had a complicated relationship with curriculum theory. For many years, the field has provided me the intellectual space to grapple with the interdisciplinary questions I want to explore about knowledge, power, and identity. Only in curriculum theory is the possibility of my academic career possible. I began writing about the public pedagogies of Black women rappers Missy Elliott, Lil Kim, and Eve in the early 2000s. Then, I took my first tenure-track position and shifted to writing about the plantation politics of predominantly white higher education spaces. Now, 20 years later, my writing is focused primarily on Black mothering. This trajectory is possible because of other Black women curriculum theorists in the space. I want to thank two sister theorists in particular for paving a way for all of us in this field, but especially me. Without Denise Taliaferro-Baszile, my work would not have been published or presented in as many places as it has been. Her work is simultaneously inspirational and aspirational for so many of us because it always manages to prompt us toward new and more complicated thinking. I want to thank also Kirsten Edwards, who has created opportunities for me to publish and present and whose work is as brilliant as it is beautifully written. She represents the Black feminist future of Afro-futurist thinking. I owe both of these women a great debt, and they will always be examples of how to pay forward all that I have been given. -

RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev

1 RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev. Rodrigo Emilio Solano-Quesnel 1 November, 2020 My friends, it’s been that kind of year… Death has been more present in our minds, in our lives, and in our communities, than what seems usual – it’s an unusual year. In addition to a number of deaths in our congregation, and in the families of our members, the global manifestation of death has been especially present as we look at the daily mounting numbers of Covid-19 cases and deaths, as attested by health authorities around the world. Blue Moon on Hallowe’en Copyright © 2020 Sarah Wert It’s been that kind of year, when mortality feels closer to our lives than we might be used to – when the risk of death feels less hypothetical, and the reality of death seems to be literally outside our doors. Many of us count among those who are called mourners, and some of us are also contemplating when mourning may once again be an immediate part of our lives. It’s been that kind of year. In our larger local community, we’ve also seen how certain systems may put some people at more risk than others. Folks who live and work in long term care, for instance, have been more prone to being infected with, and dying from, Covid-19. 2 Similarly, the way some shared accommodations are set up for some of the migrant workers in our community, also put them at higher risk of infection, and in at least three cases, dying from this pandemic’s virus. -

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING an ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING AN ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anracist.” --Angela Davis Curated Resources Jusce in June dRworksBook - Home (Dismantling Racism resources) This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea Books to read on racism and white privilege in the US Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers People Are Marching Against Racism. They’re Also Reading About It. Books to Read to Educate Yourself About An-Racism and Race An-Racist Allyship Starter Pack Black History Library An-Racism Resource List: quesons, definions, resources, people, & organizaons RESOURCES- -Showing Up for Racial Jusce Read “You want weapons? We’re in a library! Books! Best weapons in the world! This room’s the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” ― T he Doctor David Tennant Books and arcles related to anracism (general): A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integraon, and the Future of America, Calvin Baker Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Briany Cooper How to Be an Anracist , Ibram X. Kendi Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad Racism without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva So You Want to Talk about Race , Ijeoma Oluo The New Jim Crow , Michelle Alexander This Book Is An-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Acon, and Do The Work , Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand Waking Up White, White Rage; the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide , Carol Anderson White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White , Daniel Hill hps://blacklivesmaer.com/what-we-believe/ What the data say about police shoongs What the data say about police brutality and racial bias — and which reforms might work Police Violence Calls for Measures Beyond De-escalaon Training Books and arcles related to anracism in educaon: An-Racism Educaon: Theory and Pracce, George J. -

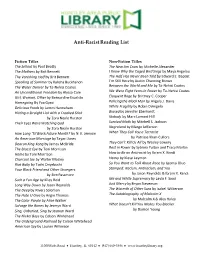

Anti-Racist Reading List

Anti-Racist Reading List Fiction Titles Non-Fiction Titles The Sellout by Paul Beatty The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Mothers by Brit Bennett I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward E. Baptist Speaking of Summer by Kalisha Buckhanon I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo Eloquent Rage by Brittney C. Cooper Homegoing By Yaa Gyasi Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis Delicious Foods by James Hannaham White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick Biased by Jennifer Eberhardt by Zora Neale Hurston Nobody by Marc Lamont Hill Their Eyes Were Watching God Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson by Zora Neale Hurston Negroland by Margo Jefferson How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin When They Call You a Terrorist An American Marriage by Tayari Jones by Patrisse Khan-Cullors Deacon King Kong by James McBride They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison Rest in Power by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin Home by Toni Morrison How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley Heavy by Kiese Laymon Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo Your Black Friend and Other Strangers Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ben Passmore by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. -

Open Mapston Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts DIGITAL ACTIVISM AND CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE BLACK LIVES MATTER GLOBAL NETWORK A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Breanna N. Mapston 2018 Breanna Mapston Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2018 ii The thesis of Breanna N. Mapston was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mary Stuckey Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Advisor Anne Demo Assistant Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Kirt Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Director of Graduate Studies of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the digital activism used by contemporary social movements by examining the Black Lives Matter Global Network (BLM). I explore several components of BLM’s digital ecology, including the organization’s website and social media accounts, to offer a renewed understanding of social movements as they appear in online contexts. I seek to understand how online messages operate rhetorically for social movements. I argue the modern movement needs an online component, although I find digital activism cannot replace the offline protests of the rhetoric of the streets. Ultimately, I offer a qualitative contribution to the study of digital activism which will serve as a prevalent form of communication for social movements now and in the future. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... v Introduction. Digital Activism and Contemporary Social Movements ....................... 1 Digital Activism .................................................................................................... 2 Outline of Study ................................................................................................... -

No Solace in the Glass Closet: Lgbtq Activists Struggle for Human Rights in Jamaica

NO SOLACE IN THE GLASS CLOSET: LGBTQ ACTIVISTS STRUGGLE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN JAMAICA By SARAH E. PAGE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sarah E. Page To all those who have suffered oppression and still choose to repair the world ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of individuals and organizations who have assisted me in bringing this dissertation into existence is extensive. First, I must thank my dissertation supervisor Faye V. Harrison, with whom this journey has been long. The very first time I met her as an undergraduate, I was in awe of her presence, her fierce intellect, and her dedication to decolonizing anthropology. She remains an inspiration to me. Even as I doubted I could reach this milestone, she insisted I could. I would not be here were it not for her. I wish to thank Leanne Brown for her long commitment to this project, as well. Her course, Crime and Governance in Jamaica led to a summer internship in Montego Bay, and the first observations that would eventually become this research. Her unflagging support of me has always managed to bolster my spirits. I offer my sincere appreciation to Dr. Abdoulaye Kane for continuing to work with me. He has been present in my graduate education from my first semester of graduate school. Under Dr. Kane’s tutelage, I had the opportunity to learn about many more African diasporas, and to expand my understanding of Afrodescendants worldwide. -

THEME: What Does Society's Approach To

THEME: What does society’s approach to safety policies reveal about its values? Discussion: Aug 13 at 7pm PT / 10pm ET Watch along on Paramount Network or BET Join our Twitter Chat during the broadcast: #TrayvonMartinStory TWITTER CHAT FEATURED GUESTS: • Bree Newsome, artist & activist, @BreeNewsome • Fresco Steez, BYP100, @thepalmtreepapi • Jonathan Jayes-Green, UndocuBlack, @JayesGreenJ DESCRIPTION: The Opportunity Agenda has partnered with Paramount Network to examine the theme of safety and what values are enforced in its name. This guide is meant to assist viewers in processing the content of the Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story docuseries and to spread awareness about the intersection and impact of racism on safety. QUESTIONS: 1) Episode 3 of Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story opens with a story of Emmett Till’s mother, whose teenage son was brutally beaten and murdered by white supremacists in 1955. How does Trayvon Martin’s murder fit into that history? 2) Florida’s Stand Your Ground law makes it legal to kill someone if it is an act of self-defense. What are the implications of this law in a society where Black people are treated as if they are inherently dangerous? 3) Gladys Zimmerman, George Zimmerman’s mother who has Afro-Peruvian roots, said in a TV interview, “We don’t see color. We are colorblind.” What does this belief reflect about society’s views on race and privilege? 4) Despite his ethnicity, we see White supremacists adopt Zimmerman as one of their own for his actions. What ideas around safety do the White supremacists use in support of Zimmerman? 5) A Tampa Bay Times investigation showed that a person accused of murder is more likely to be set free in Florida using a Stand Your Ground defense if the victim is Black. -

Sayhername: a Case Study of Intersectional Social Media Activism

Ethnic and Racial Studies ISSN: 0141-9870 (Print) 1466-4356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 #SayHerName: a case study of intersectional social media activism Melissa Brown, Rashawn Ray, Ed Summers & Neil Fraistat To cite this article: Melissa Brown, Rashawn Ray, Ed Summers & Neil Fraistat (2017): #SayHerName: a case study of intersectional social media activism, Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1334934 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334934 Published online: 14 Jun 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rers20 Download by: [The UC San Diego Library] Date: 18 June 2017, At: 11:45 ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334934 #SayHerName: a case study of intersectional social media activism Melissa Brown, Rashawn Ray, Ed Summers and Neil Fraistat Department of Sociology and Maryland Institute for Technology in Humanities, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, USA ABSTRACT Social media activism presents sociologists with the opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of how groups form and sustain collective identities around political issues throughout the course of a social movement. This paper contributes to a growing body of sociological literature on social media by applying an intersectional framework to a content analysis of over 400,000 tweets related to #SayHerName. Our findings demonstrate that Twitter users who identified with #SayHerName engage in intersectional mobilization by highlighting Black women victims of police violence and giving attention to intersections with gender identity. -

Muslim American Spokesmanship in the Age of Islamophobia

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Struggle for Recognition: Muslim American Spokesmanship in the Age of Islamophobia Nazia Kazi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/436 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE STRUGGLE FOR RECOGNITION: MUSLIM AMERICAN SPOKESMANSHIP IN THE AGE OF ISLAMOPHOBIA Nazia Kazi Dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2014 © 2014 NAZIA KAZI All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________ VINCENT CRAPANZANO Date ____________________________________ (SIGNATURE) Chair of Examining Committee _______________ GERALD CREED Date ____________________________________ (SIGNATURE) Executive Officer JEFF MASKOVSKY DANA-AIN DAVIS DEEPA KUMAR Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract The Struggle for Recognition: Muslim American Spokesmanship in the Age of Islamophobia by Nazia Kazi Advisor: Vincent Crapanzano The events of 9/11/2001 intensified the hypervisibility of U.S. Muslims, making them the subject of academic, artistic, and cultural curiosity. Alongside this public hypervisibility came a campaign of institutionalized Islamophobia, manifest in such measures as the anti-Muslim legislation of the USA PATRIOT Act. -

Out of Resistance Sparks Hope: an Afrocentric Rhetorical Analysis of Mothers of Slain Black Children

Out of Resistance Sparks Hope: An Afrocentric Rhetorical Analysis of Mothers of Slain Black Children A thesis submitted to the The University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Communication of the College of Arts and Sciences by Dominique K. Francisco B.A. University of Cincinnati Spring 2020 Committee Members: Ronald L. Jackson II, Ph.D., Eric Jenkins, Ph.D., Carlos Morrison, Ph.D. Abstract In this study, I used an Afrocentric rhetorical approach to analyze the rhetoric of mothers of slain children advocating for social justice and police reform after the deaths of black males and females at the hands of police and vigilantes. The speeches include Sybrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin and the Democratic National convention speech of the self-proclaimed group called the Mothers of the Movement. Using the metatheory of Afrocentricity and paradigmatic adaptation of Afrocentricity, the study will serve as an Afrocentric rhetorical analysis to uncover ways in which a rhetoric of social resistance can be empowering and motivating to its audience members. ii iii Acknowledgements First, I would like to express gratitude to God and my family. Thank you to the phenomenal woman that I call mom, who always supported me amid her battle with cancer. My sincere thank you goes to my advisor, Dr. Ronald L. Jackson II, thank you for your patience, motivation, and wealth of knowledge. I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Eric Jenkins and Dr. Carlos Morrison, for their encouragement and guidance. -

PIPELINES to PATHWAYS: REFRAMING and RECLAIMING BLACK YOUTH IDENTITIES THROUGH PERFORMANCE Sonny Eugene Kelly a Dissertation

PIPELINES TO PATHWAYS: REFRAMING AND RECLAIMING BLACK YOUTH IDENTITIES THROUGH PERFORMANCE Sonny Eugene Kelly A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication in the College of Arts & Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Renée Alexander Craft Alexandra Lightfoot Patricia Parker Della Pollock Katie Striley © 2020 Sonny Eugene Kelly ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Sonny Eugene Kelly: Pipelines to Pathways: Reframing and Reclaiming Black Youth Identities through Performance (Under the direction of Renée Alexander Craft) This dissertation is a critical performance-centered approach to resisting the dominant narratives that dehumanize and criminalize Black youth and perpetuate the School to Prison Pipeline in America. This approach engages the persons, perspectives, and positionalities of Black youth and their community members en route to articulating, analyzing, and addressing their experience with systemic criminalization and dehumanization. To this end, the Pipelines to Pathways project executes and examines a performance-centered process of antiracist analysis, artistry, and action for, and with, Black youth and their community members. The examination of this process is framed by critical race theory, critical interpersonal communication theory, the communication theory of identity, Goffman’s dramaturgical model of communication, and theories of critical performance and pedagogy. This examinations is based upon two case studies: (1) a performance-centered youth participatory action research project with a group of Black youth in Fayetteville, North Carolina and (2) a performed autoethnography project based upon my own experience as a Black caregiver.