Open Mapston Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gowest Newsletter Fall 2020

September 2020 Volume 1, Issue 2 Welcome back WESTies!! INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dr. Stepany Rose 2-4 Words from our Faculty We have missed you, but hope each of you had a 5 EDI Corner & Matrix Center restful summer. While things will not be traditional as we continue to navigate a global pandemic, we 6 Interviews: Dean Vidler & are still tremendously excited for what is in store Jane Muller this academic year. 6 Queer Lives Matter I hope you have had the opportunity to meet our new faculty members—Dr. ‘Ilaheva Tua’one and 7 Disclosure & Advocacy Dr. Julie Torres. Both Dr. Tua’one and Dr. Torres 8 Scholarships & Local Creators bring refreshing and critical value to our program with their much-needed areas of expertise and 8 WEST Certificates fresh approaches to Women’s and Ethnic Studies. From practical activism to addressing contemporary social justice concerns to intersectional applied theoretical analyses, their presence marks a growing vision NEWSLETTER EDITORS for WEST. Read more about them in this issue, sign up for their courses, and welcome them into our campus and community. DR. TRE WENTLING While we are all adjusting to new routines and understandings of what is “normal,” IRINA AMOUZOU (‘22) please know that we are mindful of still providing the most robust academic opportunities for you. Several new models for course offerings are available— HyFlex, remote synchronous, remote asynchronous, and traditional online. The variety of modalities have been developed to protect the health and well-being of students, faculty and staff. While this may not seem ideal, know that we are all adjusting. -

In Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

“OVERPOLICED AND UNDERPROTECTED”:1 RACIALIZED GENDERED VIOLENCE(S) IN TA-NEHISI COATES’S BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME “SOBREVIGILADAS Y DESPROTEGIDAS”: VIOLENCIA(S) DE GÉNERO RACIALIZADA(S) EN BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME, DE TA-NEHISI COATES EVA PUYUELO UREÑA Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] 13 Abstract Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015) evidences the lack of visibility of black women in discourses on racial profiling. Far from tracing a complete representation of the dimensions of racism, Coates presents a masculinized portrayal of its victims, relegating black women to liminal positions even though they are one of the most overpoliced groups in US society, and disregarding the fact that they are also subject to other forms of harassment, such as sexual fondling and other forms of abusive frisking. In the face of this situation, many women have struggled, both from an academic and a political-activist angle, to raise the visibility of the role of black women in contemporary discourses on racism. Keywords: police brutality, racism, gender, silencing, black women. Resumen Con la publicación de la obra de Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me (2015) se puso de manifiesto un problema que hacía tiempo acechaba a los discursos sobre racismo institucional: ¿dónde estaban las mujeres de color? Lejos de trazar un esbozo fiel de las dimensiones de la discriminación racial, la obra de Coates aboga por una representación masculinizada de las víctimas, relegando a las miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 62 (2020): pp. 13-28 ISSN: 1137-6368 Eva Puyuelo Ureña mujeres a posiciones marginales y obviando formas de acoso que ellas, a diferencia de los hombres, son más propensas a experimentar. -

Bardhan CV Without Jobs

Bardhan 1 SOUMIA BARDHAN Assistant Professor of Communication Department of Communication, University of Colorado Denver 1201 Larimer St, Denver, CO 80204 * [email protected] googlescholar (77 citations; h-index 4) EDUCATION Ph.D. Communication University of New Mexico, U.S. 2011 Emphasis: Intercultural/International Communication, Rhetoric, Islamic Studies Committee: Karen Foss, John Oetzel (advisors) Mary Jane Collier, Richard L. Wood, John Voll (Georgetown University) Everett Rogers Doctoral Research Scholar Awardee M.A. Communication University of Madras, India 2003 Emphasis: Mass Communication and Culture University First Rank, First Class, and Tamil Nadu Governor’s Gold Medal Awardee B.A. with Honours University of Calcutta, India 2001 Major: English Literature; Minor: Political Science, History CERTIFICATIONS Modern Standard Arabic Arabic Studies Program, Penn State University, U.S. Language Certification Beginner (2013) and Intermediate (2014) Mediation Faculty Dispute Resolution, University of New Mexico, U.S. Professional Certification 40-hour training that included examining the experience of conflict, types of conflicts, how 2008 to respond to them, dynamics of the mediation process, effective mediation/negotiation skills French Alliance Française de Madras, India Diploma Certification Level I (2002) and Level II (2003) PUBLICATIONS Book 1. Turner, P. K., Bardhan, S., Holden, T. Q., & Mutua, E. M. (Eds.). (2019). Internationalizing the Communication Curriculum in an Age of Globalization. Routledge. i. Bardhan, S. (2019). Internationalizing the communication curriculum: Benefits to stakeholders. In Turner, P. K., Bardhan, S., Holden, T. Q., & Mutua, E. M. (Eds.), Internationalizing the Communication Curriculum in an Age of Globalization. Routledge. ii. Bardhan, S., Colvin, J., Croucher, S., O’Keefe, M., & Dong, Q. (2019). -

Race and Social Justice in America

Race and Social Justice in America This list of titles available at Pasadena Public Library is compiled from suggestions from The New York Times and other publications, other public libraries, and Pasadena Public Library staff recommendations. BOOKS FOR ADULTS The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness Michelle Alexander ©2011 Despite the triumphant dismantling of the Jim Crow Laws, the system that once forced African Americans into a segregated second-class citizenship still haunts America, the US criminal justice system still unfairly targets black men and an entire segment of the population is deprived of their basic rights. Outside of prisons, a web of laws and regulations discriminates against these wrongly convicted ex-offenders in voting, housing, employment and education. Alexander here offers an urgent call for justice. 364.973 ALE I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Maya Angelou © 1969 [T]his memoir traces Maya Angelou's childhood in a small, rural community during the 1930s. Filled with images and recollections that point to the dignity and courage of black men and women, Angelou paints a sometimes disquieting, but always affecting picture of the people-and the times-that touched her life. 92 ANGELOU,M The Fire Next Time James Baldwin ©1963 The Fire Next Time contains two essays by James Baldwin. Both essays address racial tensions in America, the role of religion as both an oppressive force and an instrument for inspiring rage, and the necessity of embracing change and evolving past our limited ways of thinking about race. 305.896 BAL I Am Not Your Negro [Documentary DVD] Written by James Baldwin ©2017 Using James Baldwin's unfinished final manuscript, Remember This House, this documentary follows the lives and successive assassinations of three of the author's friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., delving into the legacy of these iconic figures and narrating historic events using Baldwin's original words and a flood of rich archival material. -

A Love Letter to Black Mothers

BERGAMO KEYNOTE, 2019 A Love Letter to Black Mothers NICHOLE A. GUILLORY Kennesaw State University A Prelude. STAYED AWAY FROM THE BERGAMO CONFERENCE on Curriculum Theory and I Classroom Practice for nearly 20 years because I have always had a complicated relationship with curriculum theory. For many years, the field has provided me the intellectual space to grapple with the interdisciplinary questions I want to explore about knowledge, power, and identity. Only in curriculum theory is the possibility of my academic career possible. I began writing about the public pedagogies of Black women rappers Missy Elliott, Lil Kim, and Eve in the early 2000s. Then, I took my first tenure-track position and shifted to writing about the plantation politics of predominantly white higher education spaces. Now, 20 years later, my writing is focused primarily on Black mothering. This trajectory is possible because of other Black women curriculum theorists in the space. I want to thank two sister theorists in particular for paving a way for all of us in this field, but especially me. Without Denise Taliaferro-Baszile, my work would not have been published or presented in as many places as it has been. Her work is simultaneously inspirational and aspirational for so many of us because it always manages to prompt us toward new and more complicated thinking. I want to thank also Kirsten Edwards, who has created opportunities for me to publish and present and whose work is as brilliant as it is beautifully written. She represents the Black feminist future of Afro-futurist thinking. I owe both of these women a great debt, and they will always be examples of how to pay forward all that I have been given. -

RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev

1 RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev. Rodrigo Emilio Solano-Quesnel 1 November, 2020 My friends, it’s been that kind of year… Death has been more present in our minds, in our lives, and in our communities, than what seems usual – it’s an unusual year. In addition to a number of deaths in our congregation, and in the families of our members, the global manifestation of death has been especially present as we look at the daily mounting numbers of Covid-19 cases and deaths, as attested by health authorities around the world. Blue Moon on Hallowe’en Copyright © 2020 Sarah Wert It’s been that kind of year, when mortality feels closer to our lives than we might be used to – when the risk of death feels less hypothetical, and the reality of death seems to be literally outside our doors. Many of us count among those who are called mourners, and some of us are also contemplating when mourning may once again be an immediate part of our lives. It’s been that kind of year. In our larger local community, we’ve also seen how certain systems may put some people at more risk than others. Folks who live and work in long term care, for instance, have been more prone to being infected with, and dying from, Covid-19. 2 Similarly, the way some shared accommodations are set up for some of the migrant workers in our community, also put them at higher risk of infection, and in at least three cases, dying from this pandemic’s virus. -

Psichologijos Žodynas Dictionary of Psychology

ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Albinas Bagdonas Eglė Rimkutė ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS Apie 17 000 žodžių ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY About 17 000 words VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA VILNIUS 2013 UDK 159.9(038) Ba-119 Apsvarstė ir rekomendavo išleisti Vilniaus universiteto Filosofijos fakulteto taryba (2013 m. kovo 6 d.; protokolas Nr. 2) RECENZENTAI: prof. Audronė LINIAUSKAITĖ Klaipėdos universitetas doc. Dalia NASVYTIENĖ Lietuvos edukologijos universitetas TERMINOLOGIJOS KONSULTANTĖ dr. Palmira ZEMLEVIČIŪTĖ REDAKCINĖ KOMISIJA: Albinas BAGDONAS Vida JAKUTIENĖ Birutė POCIŪTĖ Gintautas VALICKAS Žodynas parengtas įgyvendinant Europos socialinio fondo remiamą projektą „Pripažįstamos kvalifikacijos neturinčių psichologų tikslinis perkvalifikavimas pagal Vilniaus universiteto bakalauro ir magistro studijų programas – VUPSIS“ (2011 m. rugsėjo 29 d. sutartis Nr. VP1-2.3.- ŠMM-04-V-02-001/Pars-13700-2068). Pirminis žodyno variantas (1999–2010 m.) rengtas Vilniaus universiteto Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorijos lėšomis. ISBN 978-609-459-226-3 © Albinas Bagdonas, 2013 © Eglė Rimkutė, 2013 © VU Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorija, 2013 © Vilniaus universitetas, 2013 PRATARMĖ Sparčiai plėtojantis globalizacijos proce- atvejus, kai jų vertimas į lietuvių kalbą gali sams, informacinėms technologijoms, ne- kelti sunkumų), tik tam tikroms socialinėms išvengiamai didėja ir anglų kalbos, kaip ir etninėms grupėms būdingų žodžių, slengo, -

Framing <Anarchy> in Civic Discourse: the Profanity of Chaos

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 1-21 Framing <Anarchy> in Civic Discourse: The Profanity of Chaos Jared D. Herman Abstract Key texts circulating during the Gilded Age show how “anarchy” became a negative ideograph in political discourse. Following the work of McGee (1980), Edwards and Winkler (1997), and Cloud (2004), this work posits that <anarchy> came to be associated with evil during the Gilded Age. The ideographic function of <anarchy> is buttressed by the rhetorical force in the visual metaphor of serpents synecdochically representing anarchism during the era. Foss’s (2005) perspective approach to visual rhetoric is incorporated to illustrate how visual imagery can support the function of ideographs. The unique character of <anarchy> leaves it perpetually antithetical to “civilization,” hence opposed to <the rule of law>. The artistic use of words is paramount in political discourse. Labels can be strong points of identification for millions of U.S. citizens, especially during a presidential election season. Once a more progressive party, having championed abolition, the Republican Party appears to have taken a drastic turn towards nationalism. Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for U.S. President, has been an influential force in taking the Party further to the right, and has even received praise from the Chairman of the American Nazi Party, Rocky Suhayda (Kaczynski, 2016). On the other end of spectrum, Bernie Sanders’s inclusive and progressive platforms were frequently summarized by mainstream media outlets with a single term: “socialist.” Possibly related to being the only candidate who self-identifies with the term “socialist” tagged onto “democratic,” Sanders was largely dismissed by the popular media. -

And Visual and Performance Art in the Era of Extrajudicial Police Killings

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 5, No. 10; October 2015 Protesting Police Violence: “Blacklivesmatter” And Visual and Performance Art in the Era of Extrajudicial Police Killings John Paul, PhD Washburn University Departments of Sociology and Art Topeka, Kansas 66621 Introduction This visual essay is an exploration of the art, performance, and visual iconography associated with the BlackLivesMatter social movement organization.[1]Here I examine art that is used to protest and draw awareness to extrajudicial violence and the “increasingly militarized systems of killer cops…in the United States of America.”[2]In this review, secondary themes of racism, dehumanization, racial profiling and political and economic injustice will also be highlighted. Ultimately this work intertwines (and illustrates with art) stories of recent and historic episodes of state violence against unarmed black and brown citizens, and my goals with this project are several. First, I simply seek to organize, in one place, a record of visual protest against excessive policing. In particular, I am interested in what these images have to say about the use of state violence when compared and analyzed collectively. Second, via these images, I hope to explore the various ways they have been used to generate commentary and suggest explanations (as well as alternatives) to racism, police brutality, and a militarized culture within police departments. Within this second goal, I ask whose consciousness is being challenged, what social change is being sought, and how these images hope to accomplish this change. Third, I claim these images as part of the symbolic soul of the BlackLivesMatter social movement—and I explore the art directly within the movement as well as the art in the surrounding culture.[3] I begin however with conceptions of social movement activism. -

The Hole in the Fence: Policing, Peril, and Possibility in the US-Mexico Border Zone

The Hole in the Fence: Policing, Peril, and Possibility in the US-Mexico Border Zone, 1994-Present by Sophie Smith Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rey Chow, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Wahneema Lubiano ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman Dissertation submitted in partial FulFillment oF the requirements For the degree oF Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT The Hole in the Fence: Policing, Peril, and Possibility in the US-Mexico Border Zone, 1994-Present by Sophie Smith Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rey Chow, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Wahneema Lubiano ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman An abstract oF a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in the Graduate School oF Duke University 2016 Copyright by Sophie Smith 2016 Abstract The Hole in the Fence examines the design and efFects oF the contemporary border security regime. Since 1994, the growth oF military-style policing in the lands between the US and Mexico has radically reshaped the path oF illicit transnational migration. Newly erected walls, surveillance technology, and the stationing oF an army oF Federal agents in the border territory do not serve to seal oFF the national boundary. Border security rather works by pushing undocumented migration traFFic away From urban areas and out into protracted journeys on foot through the southwest wilderness, heightening the risks associated with entering the US without papers. Those attempting the perilous wilderness crossing now routinely Find themselves without access to water, Food, or rescue; thousands of people without papers have since perished in the vast deserts and rugged brushlands oF the US southwest. -

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING an ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING AN ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anracist.” --Angela Davis Curated Resources Jusce in June dRworksBook - Home (Dismantling Racism resources) This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea Books to read on racism and white privilege in the US Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers People Are Marching Against Racism. They’re Also Reading About It. Books to Read to Educate Yourself About An-Racism and Race An-Racist Allyship Starter Pack Black History Library An-Racism Resource List: quesons, definions, resources, people, & organizaons RESOURCES- -Showing Up for Racial Jusce Read “You want weapons? We’re in a library! Books! Best weapons in the world! This room’s the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” ― T he Doctor David Tennant Books and arcles related to anracism (general): A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integraon, and the Future of America, Calvin Baker Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Briany Cooper How to Be an Anracist , Ibram X. Kendi Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad Racism without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva So You Want to Talk about Race , Ijeoma Oluo The New Jim Crow , Michelle Alexander This Book Is An-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Acon, and Do The Work , Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand Waking Up White, White Rage; the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide , Carol Anderson White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White , Daniel Hill hps://blacklivesmaer.com/what-we-believe/ What the data say about police shoongs What the data say about police brutality and racial bias — and which reforms might work Police Violence Calls for Measures Beyond De-escalaon Training Books and arcles related to anracism in educaon: An-Racism Educaon: Theory and Pracce, George J. -

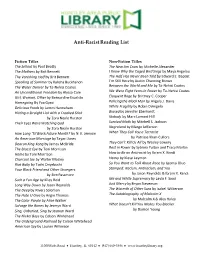

Anti-Racist Reading List

Anti-Racist Reading List Fiction Titles Non-Fiction Titles The Sellout by Paul Beatty The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Mothers by Brit Bennett I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward E. Baptist Speaking of Summer by Kalisha Buckhanon I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo Eloquent Rage by Brittney C. Cooper Homegoing By Yaa Gyasi Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis Delicious Foods by James Hannaham White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick Biased by Jennifer Eberhardt by Zora Neale Hurston Nobody by Marc Lamont Hill Their Eyes Were Watching God Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson by Zora Neale Hurston Negroland by Margo Jefferson How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin When They Call You a Terrorist An American Marriage by Tayari Jones by Patrisse Khan-Cullors Deacon King Kong by James McBride They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison Rest in Power by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin Home by Toni Morrison How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley Heavy by Kiese Laymon Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo Your Black Friend and Other Strangers Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ben Passmore by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X.