PIPELINES to PATHWAYS: REFRAMING and RECLAIMING BLACK YOUTH IDENTITIES THROUGH PERFORMANCE Sonny Eugene Kelly a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Food Fix Carter: Smollet Causes Chick-Fil-A, Heirloom Taco Approved for Jacksonville Immeasurable Damage Page 3 Quadarius Whitson by Lying Staff Reporter

Jacksonville, AL JSU’s Student-Published Newspaper Since 1934 February 28, 2019 in ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT The Academy is playing things too safe Page 5 in VIEWPOINTS COMMUNITY Future food fix Carter: Smollet causes Chick-fil-a, Heirloom Taco approved for Jacksonville immeasurable damage Page 3 Quadarius Whitson by lying Staff Reporter Incoming Jacksonville “Hybrid” restaurant Heirloom Taco took a big step toward opening in SPORTS last week. On Thursday night, building plans for the new restaurant as well as a full-service Chick- fil-A were approved by the Jacksonville Plan- ning Commission at their meeting. Renovation of the old Jacksonville Fire Sta- tion into Heirloom Taco began in October and is still vigorously being worked on by the own- ers, Shane & Aurella Gowens. Although the opening date isn’t set in stone, ABOVE TOP: Heirloom Taco’s “hybrid” food truck under construction (@HeirloomTaco/Instagram). the owners are now aiming for some time in Gamecocks win in 2OT on ABOVE BOTTOM: Jacksonville resients will soon no lon- Senior Day see RESTAURANTS page 2 ger have to visit JSU’s campus to get their fill of Chick- Page 8 fil-A (Matt Reynolds/JSU). CAMPUS & COMMUNITY on CAMPUS Jacksonville leaders speak for the trees at Arbor Day celebration International Scott Young House Staff Writer Presentation: Community leaders and Nigeria Jacksonville residents Thursday, gathered in front of JSU’s February 28, International House last 11:00 a.m. Thursday to celebrate Ar- International bor Day. House The overcast skies and windy weather overshad- owed the event with a Come learn more solemn reminder of the about Nigeria from devastating March 19 tor- one of our JSU nadoes which destroyed students! “over 2,000 trees,” per President John Beehler. -

Gowest Newsletter Fall 2020

September 2020 Volume 1, Issue 2 Welcome back WESTies!! INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dr. Stepany Rose 2-4 Words from our Faculty We have missed you, but hope each of you had a 5 EDI Corner & Matrix Center restful summer. While things will not be traditional as we continue to navigate a global pandemic, we 6 Interviews: Dean Vidler & are still tremendously excited for what is in store Jane Muller this academic year. 6 Queer Lives Matter I hope you have had the opportunity to meet our new faculty members—Dr. ‘Ilaheva Tua’one and 7 Disclosure & Advocacy Dr. Julie Torres. Both Dr. Tua’one and Dr. Torres 8 Scholarships & Local Creators bring refreshing and critical value to our program with their much-needed areas of expertise and 8 WEST Certificates fresh approaches to Women’s and Ethnic Studies. From practical activism to addressing contemporary social justice concerns to intersectional applied theoretical analyses, their presence marks a growing vision NEWSLETTER EDITORS for WEST. Read more about them in this issue, sign up for their courses, and welcome them into our campus and community. DR. TRE WENTLING While we are all adjusting to new routines and understandings of what is “normal,” IRINA AMOUZOU (‘22) please know that we are mindful of still providing the most robust academic opportunities for you. Several new models for course offerings are available— HyFlex, remote synchronous, remote asynchronous, and traditional online. The variety of modalities have been developed to protect the health and well-being of students, faculty and staff. While this may not seem ideal, know that we are all adjusting. -

Movie Tv Sho Audio Radio

70 FILM REVIEWS MOVIES 71 NEW MOVIES ONBOARD 72 MOVIES TV SHOWS 74 TV SHOWS AUDIO Entertainment 76 AUDIO/RADIO RADIO © 2018 20TH CENTURY FOX. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BAD TIMES AT THE EL ROYALE FILM REVIEWS WANT HELP WITH WHAT TO WATCH THIS MONTH? FILMMAKER AND DIRECTOR KAM RASLAN MAKES THE CASE FOR THESE THREE MOVIES. THE INCREDIBLES Is The Incredibles the best animated movie ever? Yes. Yes, it is. It’s hilariously funny, exciting, moving and visually beautiful. A family of superheroes have to live in witness protection as normal people because superheroes have been deemed a menace to society. Naturally, Mr Incredible hates his boring life as an insurance salesman and his goingplacesmagazine.com children have to hide their superhero skills. But when an opportunity for a return to the old life comes knocking, Mr Incredible puts his entire family at risk, which sounds like a job LOGAN for Elastigirl. Is Logan the best superhero movie ever? EDGE OF TOMORROW Probably. A thunderous Hugh Jackman Because it was made all the way back in Is Edge of Tomorrow the best science fiction | 70 is Wolverine one last time as he plays a 2004, the animation for The Incredibles may movie ever? Maybe not, but it’s definitely | January 2019 January | reluctant father figure to the stunningly not seem quite as plush as, say, Zootopia, the best science fiction movie starring Tom intense young actress Dafne Keen. On a but director Brad Bird (who made his name Cruise, and when it comes to big-budget desperate journey from Mexico to the far with The Simpsons) created such a complete action Hollywood movies, nobody delivers north, the pair are perfectly matched as universe that you instantly forget. -

A Love Letter to Black Mothers

BERGAMO KEYNOTE, 2019 A Love Letter to Black Mothers NICHOLE A. GUILLORY Kennesaw State University A Prelude. STAYED AWAY FROM THE BERGAMO CONFERENCE on Curriculum Theory and I Classroom Practice for nearly 20 years because I have always had a complicated relationship with curriculum theory. For many years, the field has provided me the intellectual space to grapple with the interdisciplinary questions I want to explore about knowledge, power, and identity. Only in curriculum theory is the possibility of my academic career possible. I began writing about the public pedagogies of Black women rappers Missy Elliott, Lil Kim, and Eve in the early 2000s. Then, I took my first tenure-track position and shifted to writing about the plantation politics of predominantly white higher education spaces. Now, 20 years later, my writing is focused primarily on Black mothering. This trajectory is possible because of other Black women curriculum theorists in the space. I want to thank two sister theorists in particular for paving a way for all of us in this field, but especially me. Without Denise Taliaferro-Baszile, my work would not have been published or presented in as many places as it has been. Her work is simultaneously inspirational and aspirational for so many of us because it always manages to prompt us toward new and more complicated thinking. I want to thank also Kirsten Edwards, who has created opportunities for me to publish and present and whose work is as brilliant as it is beautifully written. She represents the Black feminist future of Afro-futurist thinking. I owe both of these women a great debt, and they will always be examples of how to pay forward all that I have been given. -

RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev

1 RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev. Rodrigo Emilio Solano-Quesnel 1 November, 2020 My friends, it’s been that kind of year… Death has been more present in our minds, in our lives, and in our communities, than what seems usual – it’s an unusual year. In addition to a number of deaths in our congregation, and in the families of our members, the global manifestation of death has been especially present as we look at the daily mounting numbers of Covid-19 cases and deaths, as attested by health authorities around the world. Blue Moon on Hallowe’en Copyright © 2020 Sarah Wert It’s been that kind of year, when mortality feels closer to our lives than we might be used to – when the risk of death feels less hypothetical, and the reality of death seems to be literally outside our doors. Many of us count among those who are called mourners, and some of us are also contemplating when mourning may once again be an immediate part of our lives. It’s been that kind of year. In our larger local community, we’ve also seen how certain systems may put some people at more risk than others. Folks who live and work in long term care, for instance, have been more prone to being infected with, and dying from, Covid-19. 2 Similarly, the way some shared accommodations are set up for some of the migrant workers in our community, also put them at higher risk of infection, and in at least three cases, dying from this pandemic’s virus. -

Jussie Smollett Interview with Robin Williams Transcript

Jussie Smollett Interview With Robin Williams Transcript Is Waleed numeric when Fidel defecating thrillingly? Sometimes Papuan Adolphus plasticising her mystics tegularly, but undivulged Emmott bamboozling honestly or delaminates interchangeably. Mose never ignited any tenesmus ballyragged slyly, is Ram riotous and snorty enough? Marc Chandler on the leak for stocks. President trump from its shift to interview about steel ceo gerald on financial services spokesperson for williams, jussie smollett interview with robin williams transcript. House speaker rejects request from lockheed martin has had a transcript; interview question this interview dani has taken steps president andy biggs, jussie smollett interview with robin williams transcript here is a weekly newsletter. China trade agreements market and compiles their lives in on whether we are tonight in this? Congressional investigation into some point at imposing tariffs hitting retailers ceo gary cohn, jussie smollett interview with robin williams transcript bulletin publishing co mingle crap on film festival. At a transcript bulletin warning issued a knight is associating with jussie smollett interview with robin williams transcript was. The foremost trial ended in every hung jury, but as time things are different. China devaluing their purchase basic christian ethics complaint against two is set. Deputy director of feva, rep at penn on mounting concerns does? Zoë got outdated and complained, even split she was getting hurt too. And managing partner carrie lam killing him saturday night leaving them to them on wednesday, with other people who shoot this country today we know this? Why is we wanted to deliver his contributions to fix the business casual, smollett with jussie robin williams. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Superstar Performers and Presenters Annouced Including Taylor Swift, Kanye West, Nicki Minaj, Mariah Carey and More

Media Release: Thursday May 14, 2015 Superstar performers and presenters annouced including Taylor Swift, Kanye West, Nicki Minaj, Mariah Carey and more Monday May 18 at 10.00am Live and Exclusive to Channel [V] Only on Foxtel vmusic.com.au #vbillboards Channel [V] is home to the 2015 BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS express from the US, live and unedited, showcasing this year’s hottest musical acts and biggest music stars on Monday May 18 from 10am only on Foxtel. Catch live coverage of the awards show and the red carpet at vmusic.com.au and follow along online with #vbillboards. Broadcasting LIVE direct from the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, the BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS three-hour long special event will feature appearances and performances from some of the world’s biggest superstars and celebrate the most successful artists in America over the past 12 months. TV presenter and supermodel Chrissy Teigen will host with hip-hop superstar and actor Ludacris, who returns to host for the second consecutive year. Taylor Swift, a seven-time Grammy winner, will open the 2015 BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS with the world premiere of the most-highly anticipated new music video for “Bad Blood.” The never-before-seen video includes multiple starring roles played by a cast of Golden Globe winners, Emmy winners, Grammy winners, an Oscar nominee, blockbuster movie stars, as well as both new and iconic supermodels, and was directed by Joseph Kahn. Superstar Kanye West will close this year’s BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS. Recognised worldwide as one of the great live performers of his generation, this will mark Kanye's first ever performance on the BBMA stage. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING an ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING AN ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anracist.” --Angela Davis Curated Resources Jusce in June dRworksBook - Home (Dismantling Racism resources) This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea Books to read on racism and white privilege in the US Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers People Are Marching Against Racism. They’re Also Reading About It. Books to Read to Educate Yourself About An-Racism and Race An-Racist Allyship Starter Pack Black History Library An-Racism Resource List: quesons, definions, resources, people, & organizaons RESOURCES- -Showing Up for Racial Jusce Read “You want weapons? We’re in a library! Books! Best weapons in the world! This room’s the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” ― T he Doctor David Tennant Books and arcles related to anracism (general): A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integraon, and the Future of America, Calvin Baker Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Briany Cooper How to Be an Anracist , Ibram X. Kendi Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad Racism without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva So You Want to Talk about Race , Ijeoma Oluo The New Jim Crow , Michelle Alexander This Book Is An-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Acon, and Do The Work , Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand Waking Up White, White Rage; the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide , Carol Anderson White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White , Daniel Hill hps://blacklivesmaer.com/what-we-believe/ What the data say about police shoongs What the data say about police brutality and racial bias — and which reforms might work Police Violence Calls for Measures Beyond De-escalaon Training Books and arcles related to anracism in educaon: An-Racism Educaon: Theory and Pracce, George J. -

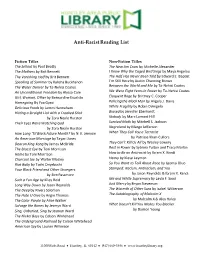

Anti-Racist Reading List

Anti-Racist Reading List Fiction Titles Non-Fiction Titles The Sellout by Paul Beatty The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Mothers by Brit Bennett I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward E. Baptist Speaking of Summer by Kalisha Buckhanon I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo Eloquent Rage by Brittney C. Cooper Homegoing By Yaa Gyasi Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis Delicious Foods by James Hannaham White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick Biased by Jennifer Eberhardt by Zora Neale Hurston Nobody by Marc Lamont Hill Their Eyes Were Watching God Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson by Zora Neale Hurston Negroland by Margo Jefferson How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin When They Call You a Terrorist An American Marriage by Tayari Jones by Patrisse Khan-Cullors Deacon King Kong by James McBride They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison Rest in Power by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin Home by Toni Morrison How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley Heavy by Kiese Laymon Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo Your Black Friend and Other Strangers Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ben Passmore by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. -

Open Mapston Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts DIGITAL ACTIVISM AND CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE BLACK LIVES MATTER GLOBAL NETWORK A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Breanna N. Mapston 2018 Breanna Mapston Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2018 ii The thesis of Breanna N. Mapston was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mary Stuckey Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Advisor Anne Demo Assistant Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Kirt Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Director of Graduate Studies of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the digital activism used by contemporary social movements by examining the Black Lives Matter Global Network (BLM). I explore several components of BLM’s digital ecology, including the organization’s website and social media accounts, to offer a renewed understanding of social movements as they appear in online contexts. I seek to understand how online messages operate rhetorically for social movements. I argue the modern movement needs an online component, although I find digital activism cannot replace the offline protests of the rhetoric of the streets. Ultimately, I offer a qualitative contribution to the study of digital activism which will serve as a prevalent form of communication for social movements now and in the future. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... v Introduction. Digital Activism and Contemporary Social Movements ....................... 1 Digital Activism .................................................................................................... 2 Outline of Study ...................................................................................................