Sayhername: a Case Study of Intersectional Social Media Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gowest Newsletter Fall 2020

September 2020 Volume 1, Issue 2 Welcome back WESTies!! INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dr. Stepany Rose 2-4 Words from our Faculty We have missed you, but hope each of you had a 5 EDI Corner & Matrix Center restful summer. While things will not be traditional as we continue to navigate a global pandemic, we 6 Interviews: Dean Vidler & are still tremendously excited for what is in store Jane Muller this academic year. 6 Queer Lives Matter I hope you have had the opportunity to meet our new faculty members—Dr. ‘Ilaheva Tua’one and 7 Disclosure & Advocacy Dr. Julie Torres. Both Dr. Tua’one and Dr. Torres 8 Scholarships & Local Creators bring refreshing and critical value to our program with their much-needed areas of expertise and 8 WEST Certificates fresh approaches to Women’s and Ethnic Studies. From practical activism to addressing contemporary social justice concerns to intersectional applied theoretical analyses, their presence marks a growing vision NEWSLETTER EDITORS for WEST. Read more about them in this issue, sign up for their courses, and welcome them into our campus and community. DR. TRE WENTLING While we are all adjusting to new routines and understandings of what is “normal,” IRINA AMOUZOU (‘22) please know that we are mindful of still providing the most robust academic opportunities for you. Several new models for course offerings are available— HyFlex, remote synchronous, remote asynchronous, and traditional online. The variety of modalities have been developed to protect the health and well-being of students, faculty and staff. While this may not seem ideal, know that we are all adjusting. -

A Love Letter to Black Mothers

BERGAMO KEYNOTE, 2019 A Love Letter to Black Mothers NICHOLE A. GUILLORY Kennesaw State University A Prelude. STAYED AWAY FROM THE BERGAMO CONFERENCE on Curriculum Theory and I Classroom Practice for nearly 20 years because I have always had a complicated relationship with curriculum theory. For many years, the field has provided me the intellectual space to grapple with the interdisciplinary questions I want to explore about knowledge, power, and identity. Only in curriculum theory is the possibility of my academic career possible. I began writing about the public pedagogies of Black women rappers Missy Elliott, Lil Kim, and Eve in the early 2000s. Then, I took my first tenure-track position and shifted to writing about the plantation politics of predominantly white higher education spaces. Now, 20 years later, my writing is focused primarily on Black mothering. This trajectory is possible because of other Black women curriculum theorists in the space. I want to thank two sister theorists in particular for paving a way for all of us in this field, but especially me. Without Denise Taliaferro-Baszile, my work would not have been published or presented in as many places as it has been. Her work is simultaneously inspirational and aspirational for so many of us because it always manages to prompt us toward new and more complicated thinking. I want to thank also Kirsten Edwards, who has created opportunities for me to publish and present and whose work is as brilliant as it is beautifully written. She represents the Black feminist future of Afro-futurist thinking. I owe both of these women a great debt, and they will always be examples of how to pay forward all that I have been given. -

RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev

1 RIP (Rest in Power) Unitarian Universalist Church of Olinda Rev. Rodrigo Emilio Solano-Quesnel 1 November, 2020 My friends, it’s been that kind of year… Death has been more present in our minds, in our lives, and in our communities, than what seems usual – it’s an unusual year. In addition to a number of deaths in our congregation, and in the families of our members, the global manifestation of death has been especially present as we look at the daily mounting numbers of Covid-19 cases and deaths, as attested by health authorities around the world. Blue Moon on Hallowe’en Copyright © 2020 Sarah Wert It’s been that kind of year, when mortality feels closer to our lives than we might be used to – when the risk of death feels less hypothetical, and the reality of death seems to be literally outside our doors. Many of us count among those who are called mourners, and some of us are also contemplating when mourning may once again be an immediate part of our lives. It’s been that kind of year. In our larger local community, we’ve also seen how certain systems may put some people at more risk than others. Folks who live and work in long term care, for instance, have been more prone to being infected with, and dying from, Covid-19. 2 Similarly, the way some shared accommodations are set up for some of the migrant workers in our community, also put them at higher risk of infection, and in at least three cases, dying from this pandemic’s virus. -

Combating Anti-Black Racism June 18, 2020

Combating Anti-black Racism June 18, 2020 Harvard University has never been entirely insulated from the dynamism of life beyond its gates. If that was not crystal clear before now, it has certainly been clarified and amplified by the profound impact of both an unexpected virus and a set of unjust murders. We share in the anger and pain reverberating across the nation in the wake of the recent instances of police brutality, white supremacist violence, and the manner in which COVID-19 is devastating black and brown communities at disproportionate rates. It is deeply saddening to hear about the untimely and preventable deaths of George Floyd (Minnesota), Breonna Taylor (Kentucky), and Ahmaud Arbery (Georgia). Furthermore, the epidemic of violence involving those who are black and transgender continues to claim lives, among them Nina Pop (Missouri) and Tony McDade (Florida). We also witnessed the weaponization of whiteness that could have led one of our graduates, Christian Cooper (New York), to share a similar fate as those aforementioned. Days ago, another shocking video surfaced capturing the final moments of Rayshard Brooks (Atlanta). The 27-year-old’s death has spurred a fresh wave of anguish and protests. These incidents are not isolated, nor are they new phenomena. Not only are they common features of black life in America, but they are probably very present in the hearts and minds of our now dispersed Harvard community. And they will likely be top of mind when we all return to campus. We have a responsibility to act with urgency. We must reckon with the structural inequality and pervasive prejudice that has led us here and work towards a future where these disparities no longer exist. -

Page 1 of 143 Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti

Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti-RacismSort All Featured White Fragility By: DiAngelo, Robin; Dyson, Michael Eric ISBN: 9780807047422 Published By: Beacon Press 2018 EPUB3 View book URL https://ebook.yourcloudlibrary.com/library/venturacountylibrary-document_id-qv1u1r9 The New York Times best-selling book exploring the counterproductive reactions white people have when their assumptions about race are challenged, and how these reactions maintain racial inequality. In this “vital, necessary, and beautiful book” (Michael Eric Dyson), antiracist educator Robin DiAngelo deftly illuminates the phenomenon of white fragility and “allows us to understand racism as a practice not restricted to ‘bad people’ (Claudia Rankine). Referring to the defensive moves that white people make when challenged racially, white fragility is characterized by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and by behaviors including argumentation and silence. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium and prevent any meaningful cross-racial dialogue. In this in-depth exploration, DiAngelo examines how white fragility develops, how it protects racial inequality, and what we can do to engage more constructively. Page 1 of 143 Let Them See You By: Braswell, Porter ISBN: 9780399581410 Published By: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale 2019 The guide to getting hired, being promoted, and thriving professionally for the 40 million people of color in the workplace—fromthe CEO and cofounder of Jopwell, the leading career advancement platform for Black, Latinx, and Native American students and professionals. Let Them See You is a collection of Braswell’s straight-talking advice and mentorship for diverse careerists, from college students to mid-level professionals. -

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING an ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR

Read, Listen, Watch, ACT BECOMING AN ANTI-RACIST EDUCATOR “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anracist.” --Angela Davis Curated Resources Jusce in June dRworksBook - Home (Dismantling Racism resources) This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea Books to read on racism and white privilege in the US Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers People Are Marching Against Racism. They’re Also Reading About It. Books to Read to Educate Yourself About An-Racism and Race An-Racist Allyship Starter Pack Black History Library An-Racism Resource List: quesons, definions, resources, people, & organizaons RESOURCES- -Showing Up for Racial Jusce Read “You want weapons? We’re in a library! Books! Best weapons in the world! This room’s the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” ― T he Doctor David Tennant Books and arcles related to anracism (general): A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integraon, and the Future of America, Calvin Baker Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Briany Cooper How to Be an Anracist , Ibram X. Kendi Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad Racism without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva So You Want to Talk about Race , Ijeoma Oluo The New Jim Crow , Michelle Alexander This Book Is An-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Acon, and Do The Work , Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand Waking Up White, White Rage; the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide , Carol Anderson White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White , Daniel Hill hps://blacklivesmaer.com/what-we-believe/ What the data say about police shoongs What the data say about police brutality and racial bias — and which reforms might work Police Violence Calls for Measures Beyond De-escalaon Training Books and arcles related to anracism in educaon: An-Racism Educaon: Theory and Pracce, George J. -

What About #Ustoo?: the Invisibility of Race in the #Metoo Movement Angela Onwuachi-Willig Abstract

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL FORUM J UNE 18, 2018 What About #UsToo?: The Invisibility of Race in the #MeToo Movement Angela Onwuachi-Willig abstract. Women involved in the most recent wave of the #MeToo movement have rightly received praise for breaking long-held silences about harassment in the workplace. The movement, however, has also rightly received criticism for both initially ignoring the role that a woman of color played in founding the movement ten years earlier and in failing to recognize the unique forms of harassment and the heightened vulnerability to harassment that women of color fre- quently face in the workplace. This Essay highlights and analyzes critical points at which the con- tributions and experiences of women of color, particularly black women, were ignored in the mo- ments preceding and following #MeToo’s resurgence. Ultimately, this Essay argues that the persistent racial biases reflected in the #MeToo movement illustrate precisely why sexual harass- ment doctrine must employ a reasonable person standard that accounts for complainants’ different intersectional and multidimensional identities. What history has shown us time and again is that if marginalized voices—those of people of color, queer people, disabled people, poor people—aren’t centered in our movements then they tend to become no more than a footnote. I o�en say that sexual violence knows no race, class or gender, but the response to it does . Ending sexual violence [and harassment] will require every voice from every corner of the world and it will require those whose voices are most o�en heard to find ways to amplify those voices that o�en go unheard. -

Beyoncé's Lemonade Collaborator Melo-X Gives First Interview on Making of the Album.” Pitchfork, 25 Apr

FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOXÍA INGLESA GRAO EN INGLÉS: ESTUDOS LINGÜÍSTICOS E LITERARIOS Beyoncé’s Lemonade: “A winner don’t quit” ANDREA PATIÑO DE ARTAZA TFG 2017 Vº Bº COORDINADORA MARÍA FRÍAS RUDOLPHI Table of Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 4 3. Beyonce's Lemonade (2016) 5 3.1 Denial: “Hold Up” 6 3.2 Accountability: “Daddy Lessons” 12 3.3 Hope: “Freedom” 21 3.4 Formation 33 4. Conclusion 44 5. Works Cited 46 Appendix 49 Abstract Beyoncé’s latest album has become an instant social phenomenon worldwide. Given its innovative poetic, visual, musical and socio-politic impact, the famous and controversial African American singer has taken an untraveled road—both personal and professional. The purpose of this essay is to provide a close reading of the poetry, music, lyrics and visuals in four sections from Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed Lemonade (2016). To this end, I have chosen what I believe are the most representative sections of Lemonade together with their respective songs. Thus, I focus on the song “Hold Up” from Denial; “Daddy Lessons” from Accountability, “Freedom” from Hope, and “Formation,” where Beyoncé addresses topics such as infidelity, racism, women’s representation, and racism and inequality. I analyse these topics through a close-reading and interpretation of Warsan Shire’s poetry (a source of inspiration), as well as Beyoncé’s own music, lyrics, and imagery. From this analysis, it is safe to say that Lemonade is a relevant work of art that will perdure in time, since it highlights positive representations of African-Americans, at the same time Beyoncé critically denounces the current racial unrest lived in the USA. -

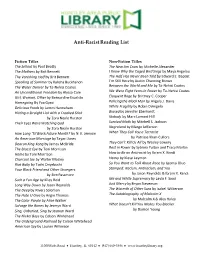

Anti-Racist Reading List

Anti-Racist Reading List Fiction Titles Non-Fiction Titles The Sellout by Paul Beatty The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Mothers by Brit Bennett I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward E. Baptist Speaking of Summer by Kalisha Buckhanon I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo Eloquent Rage by Brittney C. Cooper Homegoing By Yaa Gyasi Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis Delicious Foods by James Hannaham White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick Biased by Jennifer Eberhardt by Zora Neale Hurston Nobody by Marc Lamont Hill Their Eyes Were Watching God Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson by Zora Neale Hurston Negroland by Margo Jefferson How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin When They Call You a Terrorist An American Marriage by Tayari Jones by Patrisse Khan-Cullors Deacon King Kong by James McBride They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison Rest in Power by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin Home by Toni Morrison How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley Heavy by Kiese Laymon Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo Your Black Friend and Other Strangers Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ben Passmore by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. -

Personified Preaching: Black Feminist Sermonic Practice in Literature and Music" (2018)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Personified rP eaching: Black Feminist Sermonic Practice In Literature And Music Melanie R. Hill University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Music Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Melanie R., "Personified Preaching: Black Feminist Sermonic Practice In Literature And Music" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2884. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2884 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2884 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personified rP eaching: Black Feminist Sermonic Practice In Literature And Music Abstract ABSTRACT PERSONIFIED PREACHING: BLACK FEMINIST SERMONIC PRACTICE IN LITERATURE AND MUSIC Melanie R. Hill Dr. Herman Beavers Dr. Salamishah Tillet What does it mean when African-American culture and black rhetoric are gendered in preacherly performance discourse? This dissertation is an interdisciplinary analysis of the presence of black women preachers in both twentieth and twenty-first century African-American literature, music, and religion. Though scholarship in African-American literary and cultural studies has examined the importance of voice in black women’s cultural production, the cultural figure of the black woman preacher in literature, music, and the pulpit remains unstudied as a focus of current scholarship. Building upon the work that has been done by scholars in sound studies, this dissertation uses music to make an interdisciplinary intervention among the intersections of African-American literary criticism, music, and religious studies. -

Open Mapston Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts DIGITAL ACTIVISM AND CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE BLACK LIVES MATTER GLOBAL NETWORK A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Breanna N. Mapston 2018 Breanna Mapston Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2018 ii The thesis of Breanna N. Mapston was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mary Stuckey Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Advisor Anne Demo Assistant Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Kirt Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Director of Graduate Studies of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the digital activism used by contemporary social movements by examining the Black Lives Matter Global Network (BLM). I explore several components of BLM’s digital ecology, including the organization’s website and social media accounts, to offer a renewed understanding of social movements as they appear in online contexts. I seek to understand how online messages operate rhetorically for social movements. I argue the modern movement needs an online component, although I find digital activism cannot replace the offline protests of the rhetoric of the streets. Ultimately, I offer a qualitative contribution to the study of digital activism which will serve as a prevalent form of communication for social movements now and in the future. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... v Introduction. Digital Activism and Contemporary Social Movements ....................... 1 Digital Activism .................................................................................................... 2 Outline of Study ................................................................................................... -

No Solace in the Glass Closet: Lgbtq Activists Struggle for Human Rights in Jamaica

NO SOLACE IN THE GLASS CLOSET: LGBTQ ACTIVISTS STRUGGLE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN JAMAICA By SARAH E. PAGE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sarah E. Page To all those who have suffered oppression and still choose to repair the world ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of individuals and organizations who have assisted me in bringing this dissertation into existence is extensive. First, I must thank my dissertation supervisor Faye V. Harrison, with whom this journey has been long. The very first time I met her as an undergraduate, I was in awe of her presence, her fierce intellect, and her dedication to decolonizing anthropology. She remains an inspiration to me. Even as I doubted I could reach this milestone, she insisted I could. I would not be here were it not for her. I wish to thank Leanne Brown for her long commitment to this project, as well. Her course, Crime and Governance in Jamaica led to a summer internship in Montego Bay, and the first observations that would eventually become this research. Her unflagging support of me has always managed to bolster my spirits. I offer my sincere appreciation to Dr. Abdoulaye Kane for continuing to work with me. He has been present in my graduate education from my first semester of graduate school. Under Dr. Kane’s tutelage, I had the opportunity to learn about many more African diasporas, and to expand my understanding of Afrodescendants worldwide.