Empire Builder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

171 Abdülkerimzade Mehmed, 171 Abdullah Bin Mercan, 171

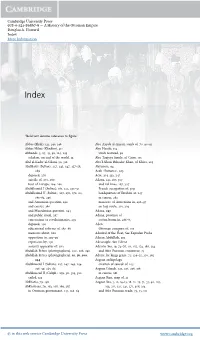

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17716-1 — Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire Abdurrahman Atçıl Index More Information Index Abdülkerim (Vizeli), 171 AliFenari(FenariAlisi),66 Abdülkerimzade Mehmed, 171 ʿAli bin Abi Talib (fourth caliph), 88 Abdullah bin Mercan, 171 Ali Ku¸sçu, 65, 66, 77n77 Abdülvahhab bin Abdülkerim, 101 Al-Malik al-Muʾayyad (Mamluk ruler), Abdurrahman bin Seydi Ali, 157, 42 157n40 Altıncızade (Mehmed II’s physician), Abdurrahman Cami, 64 80 Abu Bakr (irst caliph), 94 Amasya, 127n37, 177 Abu Hanifa, 11 joint teaching and jurist position in, ahi organization, 22 197 Ahizade Yusuf, 100 judgeship of, 79n84 Ahmed, Prince (Bayezid II’s son), 86, Anatolian principalities, 1, 20, 21, 22, 87 23n22, 24n26, 25, 26, 28, 36, 44, Ahmed Bey Madrasa, 159 64 Ahmed Bican (Sui writer), 56 Ankara, 25, 115, 178 Ahmed Pasha (governor of Egypt), 123 battle of, 25, 54 Ahmed Pasha bin Hızır Bey. See Müfti joint teaching and jurist position in, Ahmed Pasha 197 Ahmed Pasha bin Veliyyüddin, 80 Arab Hekim (Mehmed II’s physician), Ahmed Pasha Madrasa (Alasonya), 80 161 Arab lands, 19, 36, 42, 50, 106, Ahmedi (poet), 34 110n83, 119, 142, 201, 202, ʿAʾisha (Prophet’s wife), 94 221 Akkoyunlus, 65, 66 A¸sık Çelebi, 10 Ak¸semseddin, 51, 61 A¸sıkpa¸sazade, 38, 67, 91 Alaeddin Ali bin Yusuf Fenari, 70n43, Ataullah Acemi, 66, 80 76 Atayi, Nevizade, 11, 140, 140n21, Alaeddin Esved, 33, 39 140n22, 194, 200 Alaeddin Pasha (Osman’s vizier), 40 Hadaʾiq al-Haqaʾiq, 11, 206 Alaeddin Tusi, 42, 60n5, 68n39, 81 Ayasofya Madrasa, 60, 65, 71, -

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland As Cultural Mediators

Chapter 10 Connectivity, Mobility, and Mediterranean “Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland as Cultural Mediators Gülru Necipoğlu Considering the mobility of persons and stones is one way to reflect upon how movable or portable seemingly stationary archaeological sites might be. Dalmatia, here viewed as a center of gravity between East and West, was cen- tral for the global vision of Ottoman imperial ambitions, which peaked during the 16th century. Constituting a fluid “border zone” caught between the fluctu- ating boundaries of three early modern empires—Ottoman, Venetian, and Austrian Habsburg—the Dalmatian coast of today’s Croatia and its hinterland occupied a vital position in the geopolitical imagination of the sultans. The Ottoman aspiration to reunite the fragmented former territories of the Roman Empire once again brought the eastern Adriatic littoral within the orbit of a tri-continental empire, comprising the interconnected arena of the Balkans, Crimea, Anatolia, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa. It is important to pay particular attention to how sites can “travel” through texts, drawings, prints, objects, travelogues, and oral descriptions. To that list should be added “traveling” stones (spolia) and the subjective medium of memory, with its transformative powers, as vehicles for the transmission of architectural knowledge and visual culture. I refer to the memories of travelers, merchants, architects, and ambassadors who crossed borders, as well as to Ottoman pashas originating from Dalmatia and its hinterland, with their extraordinary mobility within the promotion system of a vast eastern Mediterranean empire. To these pashas, circulating from one provincial post to another was a prerequisite for eventually rising to the highest ranks of vizier and grand vizier at the Imperial Council in the capital Istanbul, also called Ḳosṭanṭiniyye (Constantinople). -

Analysis of Documentation About Ottoman Heritage in Belgrade Via Digital Reconstruction of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Caravanserai

Vladimir BOŽİNOVİĆ, Viktor POPOVİĆ* ANALYSIS OF DOCUMENTATION ABOUT OTTOMAN HERITAGE IN BELGRADE VIA DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF SOKOLLU MEHMED PASHA CARAVANSERAI This city as wonderful as a diamond in a ring was founded by one of the Serbian kings, King Despot. It was the conquest goal for all kings wrote in 1660 Evliya Çelebi. Abstract In the period from 16th to the end of the 17th century Belgrade became one of the most important cities of Ottoman Empire in the Balkans. During this era of peace Sultans and Grand Viziers erected numerous waqf endowments, which formed an enviable economic, educational and religious center. Most important Belgrade waqf was certainly the waqf of Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmet Pasha. It consisted out of several buildings with the most famous one being vizier`s caravanserai, probably the biggest architectural complex of Ottoman Belgrade. In the following centuries, the city was constantly changing power and turmoil that followed many savage bat- tles resulted in destruction of famous caravanserai and many other monuments of Ottoman Bel- grade. The only testimony of these glorious objects that we have today is partial documentation scattered throughout museums and archives in Serbia and abroad. Modern means of recon- 1 struction of cultural heritage through analysis of available documentation reveal new possibili- * Felsefe Fakültesi, Belgrat- SIRBİSTAN. Balkanlarda Osmanlı Vakıfları ve Eserleri Uluslararası Sempozyumu / 341 ties for further study and presentation of Ottoman heritage in Belgrade. Now we can revitalize politicized or neglected historic heritage with virtual forms of presentation which would promote cultural tolerance and real identity reference of Belgrade. This approach will be discussed through the example of digital reconstruction of Sokollu Meh- met Pasha caravanserai. -

5989 Turcica 35 09 Reindl

Hedda REINDL-KIEL 247 THE TRAGEDY OF POWER THE FATE OF GRAND VEZIRS ACCORDING TO THE MENAKIBNAME-I MAHMUD PA≤A-I VELI bhorrence of tyranny and bloodthirsty despotism is, according to A 1 Joseph von Hammer , a prominent leitmotiv in the anonymous Mena- kıbname-i Mahmud Pa≥a. Hammer remarks, though, that its text cannot serve as a historical source, but is rather a kind of coffeehouse literature (lowbrow narratives presented by a story teller). Following this verdict, scholars did not show any particular interest in the menakıb for a lengthy period, although the text was printed in Turkey in the second half of the 19th century2. In 1854 an edition (using the manuscript Dresden Cod. turc. 181 and one of the Berlin manuscripts) with a French translation appeared in Friedrich Heinrich Dieterici's Chrestomatie Ottomane3, but this served largely didactic purposes. Thus, the view of scholars did not change, and Franz Babinger remarked as late as 1927 in his Geschichts- schreiber der Osmanen that the menakıb were of no historical value4. In 1949, Halil Inalcık and Mevlûd Oguz introduced a newly-found “∞gazavat-ı Sultan Murad∞”, which contained at the end an incomplete Dr. Hedda REINDL-KIEL Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Nassestr. 2 D-53113 Bonn, Germany. 1 Joseph von HAMMER, Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches, vol. IX, Pest 1833 (reprint∞: Graz 1963), p. 238, no 116. 2 Niyazi Ahmed BANOGLU, Mahmud Pa≥a∞—∞Hayatı ve ≤ehadeti∞—(Camilerimiz ve Bâniler), Istanbul, 1970 (Gür Kitapevi), p. 8. 3 Berlin, p. 1-18 (Ottoman text), 63-81 (French translation). -

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

The Ottoman Age of Exploration

the ottoman age of exploration the Ottomanof explorationAge Giancarlo Casale 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dares Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Casale, Giancarlo. Th e Ottoman age of exploration / Giancarlo Casale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8 1. Turkey—History—16th century. 2. Indian Ocean Region—Discovery and exploration—Turkish. 3. Turkey—Commerce—History—16th century. 4. Navigation—Turkey—History—16th century. I. Title. DR507.C37 2010 910.9182'409031—dc22 2009019822 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper for my several -

3 Introducing the Ottoman Empire 49 4 Scholars in Mehmed II’S Nascent Imperial Bureaucracy (1453–1481) 59 5 Scholar-Bureaucrats Realize Their Power (1481–1530) 83

Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire During the early Ottoman period (1300–1453), scholars in the empire carefully kept their distance from the ruling class. This changed with the capture of Constantinople. From 1453 to 1600, the Ottoman government coopted large groups of scholars, usually more than a thousand at a time, and employed them in a hierarchical bureaucracy to fulfill educational, legal, and administrative tasks. Abdurrahman Atçıl explores the factors that brought about this gradual transformation of scholars into scholar- bureaucrats, including the deliberate legal, bureaucratic, and architectural actions of the Ottoman sultans and their representatives, scholars’ own participation in shaping the rules governing their status and careers, and domestic and international events beyond the control of either group. abdurrahman atçıl is Assistant Professor and a fellow of the Brain Circulation Scheme, co-funded by the European Research Council and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey, at IstanbulSehir ¸ University. He also holds an assistant professorship in Arabic and Islamic studies at Queens College, City University of New York. Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Cambridge University Library, on 13 Feb 2017 at 10:56:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316819326 Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Cambridge University Library, on 13 Feb 2017 at 10:56:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316819326 Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire abdurrahman atçıl Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. -

Introduction

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/69483 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bekar C. Title: The rise of the Köprülü family: the reconfiguration of vizierial power in the seventeenth century Issue Date: 2019-03-06 INTRODUCTION When Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, at the age of almost seventy, was appointed as grand vizier on 15 September 1656, few would have thought that he was to become one of the most powerful and independent grand viziers in Ottoman history. Köprülü Mehmed Pasha was the sixth grand vizier to take office within a single year.1 The preceding five grand viziers came and went, some within a matter of weeks. They either faced dismissal or chose to resign from the position. Moreover, the inception of Köprülü Mehmed Pasha’s grand vizierate coincided with one of the most critical and tumultuous times of the seventeenth century. Since 1645, the war with Venice over Crete had exhausted Ottoman manpower and the treasury, engendering great turmoil in the capital. 2 A few months before Köprülü Mehmed was appointed, the Ottoman navy suffered its worst defeat of the war. Following their victory, the Venetians blockaded the straits, which meant cutting off food supplies to Istanbul from Egypt. Under these dire conditions, it was a commonly held view that Köprülü Mehmed Pasha would not last long in office.3 The French ambassador of the time, M.de la Haye Vantelay also shared this opinion, and he therefore neither paid a visit to Köprülü Mehmed Pasha nor presented the customary royal gifts.4 In contrast to general expectations, Köprülü Mehmed Pasha remained in the office until his death in 1661. -

The Sokollu Family Clan and the Politics of Vizierial

Uroš Dakiü THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2012 THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2012 ii THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2012 iii THE SOKOLLU -

FACTIONS and FAVORITES at the COURTS of SULTAN AHMED I (R. 1603-17) and HIS IMMEDIATE PREDECESSORS

FACTIONS AND FAVORITES AT THE COURTS OF SULTAN AHMED I (r. 1603-17) AND HIS IMMEDIATE PREDECESSORS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Günhan Börekçi Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Jane Hathaway, Chair Professor Howard Crane Professor Stephen F. Dale Copyright by Günhan Börekçi 2010 All rights reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the changing dynamics of power and patronage relations at the Ottoman sultan’s court in Istanbul between the 1570s and the 1610s. This was a crucial period that many scholars today consider the beginning of a long era of “crisis and transformation” in the dynastic, political, socio-economic, military and administrative structures of the early modern Ottoman Empire. The present study focuses on the politics of factionalism and favoritism at the higher echelons of the Ottoman ruling elite who were situated in and around Topkapı Palace, which served as both the sultan’s royal residence and the seat of his imperial government. It is an effort to shed light on the political problems of this period through the prism of the paramount ruling figure, the sultan, by illustrating how the Ottoman rulers of this era, namely, Murad III (r. 1574-95), Mehmed III (r. 1595-1603) and Ahmed I (r. 1603-17), repositioned themselves in practical politics vis-à-vis alternative foci of power and networks of patronage, and how they projected power in the context of a factional politics that was intertwined with the exigencies of prolonged wars and incessant military rebellions. -

Istanbul in Mimar Sinan's Footsteps

1 Pertev Pasha Tomb 19 Sultan Selim I Medrese Originally an Albanian, Pertev Mehmet Pasha served as a Vizier during the reigns of Built in his father’s name on the orders of Suleiman the Magnificent, the medrese consists 30 Şehzade Mehmet Tabhane 40 Molla Çelebi Mosque Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim II. He commissioned Sinan to build a large külliye of a series of porticoed student rooms lined up around a courtyard and a large dershane Similar to Fatih Mosque, Şehzade Mehmet Mosque does not have an integrated tabhane According to the vakfiye (endowment charter) of the mosque from 1570, the complex was (complex) in İzmit and had his tomb constructed in Istanbul while he was still alive. (main classroom) that is used as a small mosque. Unlike the rest of the structure, the (guesthouse). Instead the tabhane was designed as a separate building in the külliye and designed as a small külliye. Sinan built its hamam and mosque, which has a hexagonal dershane is built with limestone accentuates the importance of the dershane. has design references to the early periods of Ottoman architecture. The building consists plan. The sıbyan mekteb (children’s Koran school) and hamam have not reached our day. 2 Tomb of Siyavuş Pasha’s Son of two symmetrical parts covered with a dome with a cupola in the middle and four The tomb is situated inside a large courtyard and three of its walls go beyond the 20 Hüsrev Çelebi (Ramazan Efendi) Mosque domed sections surrounding the covered hall therein. 41 Sinan Pasha Mosque courtyard wall.