Memorable Sephardi Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Readings on the Encounter Between Jewish Thought and Early Modern Science

HISTORY 449 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA W 3:30pm-6:30 pm Fall, 2016 GOD AND NATURE: READINGS ON THE ENCOUNTER BETWEEN JEWISH THOUGHT AND EARLY MODERN SCIENCE INSTRUCTOR: David B. Ruderman OFFICE HRS: M 3:30-4:30 pm;W 1:00-2:00 OFFICE: 306b College Hall Email: [email protected] SOME GENERAL WORKS ON THE SUBJECT: Y. Tzvi Langerman, "Jewish Science", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 11:89-94 Y. Tzvi Langerman, The Jews and the Sciences in the Middle Ages, 1999 A. Neher, "Copernicus in the Hebraic Literature from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century," Journal History of Ideas 38 (1977): 211-26 A. Neher, Jewish Thought and the Scientific Revolution of the Sixteenth Century: David Gans (1541-1613) and His Times, l986 H. Levine, "Paradise not Surrendered: Jewish Reactions to Copernicus and the Growth of Modern Science" in R.S. Cohen and M.W. Wartofsky, eds. Epistemology, Methodology, and the Social Sciences (Boston, l983), pp. 203-25 H. Levine, "Science," in Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought, eds. A. Cohen and P. Mendes-Flohr, l987, pp. 855-61 M. Panitz, "New Heavens and a New Earth: Seventeenth- to Nineteenth-Century Jewish Responses to the New Astronomy," Conservative Judaism, 40 (l987-88); 28-42 D. Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science: The Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth- Century Jewish Physician, l988 D. Ruderman, Science, Medicine, and Jewish Culture in Early Modern Europe, Spiegel Lectures in European Jewish History, 7, l987 D. Ruderman, Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe, 1995, 2001 D. Ruderman, Jewish Enlightenment in an English Key: Anglo-Jewry’s Construction of Modern Jewish Thought, 2000 D. -

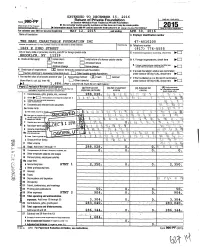

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Keter Shem Tov: a Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only

Keter Shem Tov: A Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only Keter Shem Tov: A Study in the Entitling of Books, Here Limited to One Title Only[1] by Marvin J. Heller Entitling, naming books is, a fascinating subject. Why did the author call his book what he/she did? Why that name and not another? Hebrew books frequently have names resounding in meaning, but providing little insight into the contents of the book. This article explores the subject, focusing on one title only, Keter Shem Tov. That book-name is taken from a verse “the crown of a good name (Keter Shem Tov) excels them all (Avot 4:13). The article describes the varied books with that title, unrelated by author or subject, and why the author/publisher selected that title for the book. 1. Simeon said: there are three crowns: the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood, and the crown of royalty; but the crown of a good name (emphasis added, Keter Shem Tov) excels them all (Avot 4:13). “As a pearl atop a crown (keter), so are his good deeds fitting” (Israel Lipschutz, Zera Yisrael, Avot 4:13). Entitling, naming books, remains, is, a fascinating subject. Why did the author call his book what he/she did? Why that name and not another? Hebrew books since the Middle-Ages often have names resounding in meaning, but providing little insight into the contents of the book. A reader looking at the title of a book in another language, more often than not, is immediately aware of the book’s subject matter. -

David Ricardo's Sefarad

David Ricardo’s Sefarad Sergio Cremaschi Former Professor of Moral Philosophy Amedeo Avogadro University (Alessandria, Novara, Vercelli) ESHET XXII Conference Madrid 7-9 June 2018 1. A blind spot in Ricardo’s biography This paper is meant to be a contribution to a reconstruction of an aspect of Ricardo’s biography, namely the history of his shifting religious affiliations with their biographical, intellectual and political implications. Here I examine the first 21 years of his life, when he was a child in a London Sephardi household and, from the age of 13, a member of the Bevis Mark congregation. My aim is – given the scarcity of primary sources – to add something to the accounts available (Sraffa 1955, 16-43 and 54-61; Heertje 1970; 1975; 2015; Weatherall 1976, 1-21; Henderson 1997, 51-154) by taking advantage of two tools by which to squeeze a bit more out of scant documents. The first is a contextual approach, made possible now by excellent work that has been done by historians on eighteenth-century Anglo-Judaism. The second is pragmatic interpretation of utterances recorded in documents, a technique that may be learned from the no less valuable work done by philosophers of language, one of Sraffa’s close friends no less than the whole Oxford philosophy which the latter did not appreciate too much, John Austin, John Searle and Paul Grice. I contend, first, that something more may be learnt on Ricardo’s formative years, on religion, moral education, intellectual interests awakened and competences acquired, than Sraffa and other biographers -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 5 The Sound Issue “Overtures” Music, the “Jew” of Jewish Studies: Updated Readers’ Digest 6 Edwin Seroussi To Hear the World through Jewish Ears 9 Judah M. Cohen “The Sound of Music” The Birth and Demise of Vocal Communities 12 Ruth HaCohen Brass Bands, Jewish Youth, and the Sonorities of a Global Perspective 14 Maureen Jackson How to Get out of Here: Sounding Silence in the Jewish Cabaretesque 20 Philip V. Bohlman Listening Contrapuntally; or What Happened When I Went Bach to the Archives 22 Amy Lynn Wlodarski The Trouble with Jewish Musical Genres: The Orquesta Kef in the Americas 26 Lillian M. Wohl Singing a New Song 28 Joshua Jacobson “Sounds of a Nation” When Josef (Tal) Laughed; Notes on Musical (Mis)representations 34 Assaf Shelleg From “Ha-tikvah” to KISS; or, The Sounds of a Jewish Nation 36 Miryam Segal An Issue in Hebrew Poetic Rhythm: A Cognitive-Structuralist Approach 38 Reuven Tsur Words, Melodies, Hands, and Feet: Musical Sounds of a Kerala Jewish Women’s Dance 42 Barbara C. Johnson Sound and Imagined Border Transgressions in Israel-Palestine 44 Michael Figueroa The Siren’s Song: Sound, Conflict, and the Politics of Public Space in Tel Aviv 46 Abigail Wood “Surround Sound” Sensory History, Deep Listening, and Field Recording 50 Kim Haines-Eitzen Remembering Sound 52 Alanna E. Cooper Some Things I Heard at the Yeshiva 54 Jonathan Boyarin The Questionnaire What are ways that you find most useful to incorporate sound, images, or other nontextual media into your Jewish Studies classrooms? 56 Read AJS Perspectives Online at perspectives.ajsnet.org AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of President Please direct correspondence to: the Association for Jewish Studies Pamela Nadell Association for Jewish Studies From the Editors perspectives.ajsnet.org American University Center for Jewish History 15 West 16th Street Dear Colleagues, Vice President / Program New York, NY 10011 Editors Sounds surround us. -

Contents Production

Contents WAR STORIES IN THE MAIL ..................... 2 uring the mid-summer months, Israelis not Donly had the sweltering heat on their minds NUPTIALS ..........................5 — June marked the fortieth anniversary of the PEOPLE .............................6 Six Day War; July, the first anniversary of the 7 Second Lebanese War. With our soldiers in STUDENT AFFAIRS ...........15 captivity, the Nation felt it was a time to reflect COVER STORY ..................21 rather than to celebrate. FOCUS ON TELFED ..........28 But are we not a little hard on ourselves? NOTICE BOARD ................32 Do we aspire to such high ideals that we fail to recognize success? Both conflicts are recalled NEW ArrivALS .................34 in this Telfed as we record the recollections and 15 SPORT .............................38 insights of former Southern Africans caught up in war as volunteers, civilians or in uniform. KEREN TELFED ................40 “I was in Cape Town during the Six Day BUSINESS ........................44 War,” said Muriel Chesler today a resident at IN MEMORIAM..................46 Beth Protea. “We thought the end of the world had come.” She was hardly alone with those CLAssifiEds ....................47 38 apocalyptic thoughts. And yet today, forty years on, the nation is strong. Israel is a vibrant Production democracy in a neighbourhood of autocracies. Editor and Chief Correspondent: David Kaplan Its economy is booming and our universities Design and Layout: Becky Rowe are churning out graduates that will spearhead Editorial Committee Chairman: Dave Bloom our small country into a big future. Media Committee: Dave Bloom (Chair), Sharon And if immigration is down, it should not Bernstein, Gershon Gan, Pearl Feldman, David get us down. -

990-PF Return of Private Foundation

I EXTENDED TO DECEMBER 15, 2016 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(axl) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Depertrnent or the rreasu y Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2015 Internal Revenue Service 00, Information about Form 990-PF and its separate Instructions Is at Wt ny rrs. ov/fort en o u is ns ec ion For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning MAY 12 , 201 5 and ending APR 016 Name of foundation Employer identification number THE MARI CHARI TABLE FOUNDATION INC 47-4010200 Number and street (a P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) RooMswte B Telephone number 1869 E 23RD STREET (917) 776-5555 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► BROOKLYN, NY 11229 G Check all that apply. XD Initial return initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address chan ge Name chan ge check here and attach computation H Check type of organization: [X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: MX Cash 0 Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. -

November 2001

m TELFED NOVEMBER i001 VOL. 27 NO. 3 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THE U.N. CONFERENCE ON R A C I S M I N D U R B A N D m \ m ( a ® M ^ M [ n r i f ^Dr.Ya'akov Kat/.. new face at the Minisuy of Education: Ariann Waliach, deer to ine: Impressions ofllie Durban NUPTIALS, ARRIVALS.... Bnoih Zioii CciUenar>'.... CoiiCcrencc AND MORE THE PRiNTINC AND DISTRIBUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA OF THIS ISSUE OF TELFED MAGAZINE IS SPONSORED BY THE IMMIGRATION AND ABSORPTION DEPARTMENT OF THE JEWISH AGENCY FOR ISRAEL. Because quality of life on a five-star level was always a prime consideration for us, we decided to turn it into a way of life This was the guideline that led us to Protea Village, where Itzak & Renate Unna everything is on a five-star level: tlie spacious homes, private gardens, 19 dunams of private park, central location in the heart of the Sharon, building standard, meticulous craftsmanship, Apartments for variety of activities, and most important of all, personal and immediate Occupation medical security for life. >^"'■"$159,000 To tell the truth, this is the only place where we found quality of life on a par with what we have seen throughout the world. B n e i D r o r J u n c t i o n Proteal^^Village * ' M R * h a n i n ^ u n c i i o n FIVE STAR RETIREMENT VILLAGE K , B o a D n r / t n r a c B - You're invited to join! 9 Ri&um Kft^Soba For further details, please phone: 1-800-374-888 or 09-796-7173 CONTENTS O F F T H E W A L L INTHEMAIL 1 in exasperation, wailing - we are all alone. -

The Case of the Pineapple

J. David Bleich SURVEY OF RECENT HALAKHIC LITERATURE TREES AND PLANTS: THE CASE OF THE PINEAPPLE n the United States the presence of pineapple is ubiquitous on fes- tive and not so festive occasions. Not so in pre-World War II European I communities. Immigrants to this country embraced the pineapple as an affordable treat rather than as an expensive luxury. But the pineapple was not embedded in their culinary culture and hence there was no ac- companying tradition for its halakhic characterization. Cultivated on rela- tively low-growing plants, it was simply presumed to be analogous to a vegetable. Long ago, Socrates declared, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”1 The halakhic counterpart would be “The unexamined foodstuff may not be consumed.” The Gemara, Berakhot 35a, declares that if a person is in doubt with regard to a rule governing blessings he dare not partake of the food in question until that doubt is resolved: “Let him fi rst go to a wise man to teach him blessings so that he not commit me’ilah,” i.e., illicit appropriation of property belonging to the Deity.2 The American Torah community has achieved a level of halakhic knowledge and sophistication such that unexamined premises are no lon- ger regarded as acceptable as a matter of course. That sophistication has brought with it a keen awareness that many heretofore unexamined hal- akhic issues require analytic refl ection. The status of food products in general is one such area and that of the pineapple is a prime example. Some simply refrained from eating pineapples because they became aware of the existence of an issue, albeit one that, more often than not, they could not articulate in a knowledgeable manner.